The Saturday Read: Blasted skylines

Inside: Yahya Sinwar, the Budget, le Carré, Liam Payne, John Gray on Malcolm Gladwell and a new poem from Margaret Atwood.

Good morning. Welcome to the Saturday Read, the New Statesman’s guide to politics, culture, books, and ideas. This is Jason, together with Finn, Nicholas, Pippa and George.

What did Yahya Sinwar, the leader of Hamas in Gaza who was killed by IDF troops this week as he was hiding out in a ruined building in Rafah in the south of the besieged Strip, want when he sent his well-trained death squads into Israel on 7 October 2023? How many of his fellow Palestinians was he prepared to see die in return? Sinwar was a brutal anti-Semite and uncompromising Islamist, but he was not irrational. He must have known how Israel under the leadership of Benjamin Netanyahu would respond to the murderous attacks, the onslaught on Gaza that would follow as Israel, through necessity on a permanent war-footing, demanded retribution and enhanced security for its citizens.

During the long years Sinwar spent in prison in Israel – he was released in the prisoner exchange deal that was brokered when Gilad Shalit, the IDF soldier held captive in Gaza, was returned home in 2011 – he was a diligent student of Hebrew and Israeli history. He was relentless, strategic, patient, and completely ruthless. And he believed he knew his enemy well.

In just over a year, much of the densely populated Strip has become uninhabitable. Small cities and towns have been bombed into ruin and as many as 42,000 Palestinians have been killed, according to the Hamas-controlled Gaza Health Ministry – many of them Hamas fighters but many of them also women and children. International journalists are prevented by Israel from entering Gaza. The full truth of the horror inside the Strip is, therefore, unknown. But the suffering of civilians is perpetual.

Israel is fighting wars on multiple fronts now as it prepares for a retaliatory strike on Iran, the despotic clerical regime that is the ultimate sponsor of terror in the Middle East. The region is in flames. The Palestinian cause has caught the world’s attention once more. The Saudi Arabia-Israel rapprochement is on hold. Sinwar, presumably, died satisfied. The “tunnel rat” as he was known in Israel was wearing army fatigues and was throwing grenades to the last.

In March I visited the Kibbutz Kfar Aza, which is perhaps a mile from the Gaza border. A terrible massacre occurred there on the morning of 7 October and some residents of the kibbutz were taken hostage. Our armed guide was Zohar Shpek, a former police lawyer and one of the few to have returned to Kfar Aza back then. He was a self-described peacenik, a lefty activist: he had always campaigned for peace. “We built relationships with Palestinians – sending aid and provisions into Gaza,” he said.

He was asked how he felt about the plight of the people of Gaza, and I’ve often reflected on his reply. “I don’t care about them,” he said. “I care only about people this side of the border. My vision didn’t change from 20 years ago. I’m a peacenik. But I can no longer go to help an Arab child. I can only help my child. We are fighting for our lives.”

As he spoke you could hear the boom of artillery being fired into the Strip.

Sinwar is dead, Hamas has been crushed, the threat to Israel from Gaza is contained, and yet for either side – for all sides – there seems to be no alternative to war. Everyone believes they are fighting for their lives.

The picks…

Good morning, Finn here. The New Statesman published its autumn book special this week. So, alongside pieces on the approaching Budget and extraordinary news of Yahya Sinwar’s death, we have piles of great reviews and essays. John le Carré’s George Smiley is resurrected on the page; John Gray finds Malcolm Gladwell unconvincing; and Naomi Klein pays tribute to Arundhati Roy. You’ll find plenty more below, in the magazine and across the website. To sign us off – a new poem by Margaret Atwood.

1—“The social democratic Margaret Thatcher”

This month’s budget is not just an opportunity for Labour to reset its optics, but necessary for the health of the nation. “Invest – or decline” as Rachel Reeves puts it to Andrew Marr. Andrew came away from meeting our “Iron Chancellor” with a rare political quantity: hope. NH

“I’m going to be the Chancellor that does things differently. We’re going to get to that growth, improve living standards and improve our public services.” Not a flicker of self-doubt. In a previous interview with Reeves in these pages, the New Statesman distinguished between Rachel One, cautious Rachel, and Rachel Two, radical Rachel. Which is it? Both, perhaps: “You’ve got to be credible.” I come away feeling I’ve met a genuinely Labour Chancellor, a woman clear that she is in the Treasury to help ordinary people on ordinary budgets, prepared to take on powerful critics over tax rises, and with a real optimism about the room for growth and the future: “We’re going to make the long-term decisions to get our country back on its feet.”

2—“I can’t tell you if they are good”

To mark the release of Disney’s Rivals adaptation, Tanya Gold revisits the novels of Jilly Cooper – so absurd they’re rarely the subject of serious analysis – and finds them as much about class as about sex. PB

I interviewed her 20 years ago in her house in the Cotswolds: an embroidered sign on the front door said: “Go away”. Did she mean it? No interviewee has made me lunch before or sent me flowers after, but she did. She has good manners – superficially, the dominant characteristic of the British aristocrat – and journalists have, in return, wound protective spells around her. She is rarely criticised: she is barely even analysed. In this, we mirror her novels, in which she makes the nobility more interesting – and stupider – than it really is. People say Cooper’s novels are about sex, and the sex is hard to ignore. Rupert Campbell-Black, who appears in all eleven novels, has a “cock like a baseball bat. Used to bat bread rolls across the room with it when we were at school.”

3—“This dangerous new chapter”

The announcement of Arundhati Roy’s PEN Pinter Prize came with reports that she might soon face charges under India’s draconian anti-terrorism laws. Naomi Klein discusses Roy’s “seditious heart” and how it equips us for perilous times. GM

After 9/11, when George W Bush declared “you are either with us or with the terrorists”, Roy reminded us then that we did not have to choose between “a malevolent Mickey Mouse and the Mad Mullahs” – that all the beauty on Earth existed between those two poles. Or when US fighter jets pummelled Afghanistan with bunker busters, and then followed up by airdropping packets of food aid, and Roy described the display as “brutality smeared in peanut butter and strawberry jam”. Or what she said about the way our phones have become extensions of bodies: “Imagine if your liver or your gallbladder didn’t have your best interest at heart.” Or her scathing take on middle class, professionalised environmentalism, which, she says, “Asks the question: How can we change without changing?”

4—“Liam Payne was dehumanised his entire life”

We do not yet know the exact circumstances of Liam Payne’s death. But we know that in his short life the music industry, the media and even his own fans collaborated to humiliate and deride him. “How many victims,” Anna Leszkiewicz asks, “does the pop music industry have to produce before something changes?” NH

He became a pin-up poster, then a literal doll (you could collect all five). The documentary concert film This Is Us, released at the peak of One Direction’s fame in 2013, is, on the surface, a group portrait of the band’s shared, antic boyhood on stage. But it reveals the punishing extent of their tour and recording schedule, and the isolating effects of celebrity. In one scene Payne’s mother buys a cardboard cut-out of her own son: “I shed tears just looking at him. You’ve only got the images. They become someone in a newspaper or a magazine to you.”

5—“Archetypal airport books”

Malcolm Gladwell’s Tipping Point (2000) was poptimism in the guise of academic psychology. Now, 24 years later Gladwell has returned to his seminal theory – that entire social epidemics can be triggered by very few people – in Revenge of the Tipping Point. John Gray isn’t convinced, contending that Gladwell avoids awkward facts, and leaves the reader entertained but no wiser. FMcR

Like liberal rationalists everywhere, Gladwell assumes that smart people will be benign. Evil is error, a lapse in understanding for which knowledge is the sovereign remedy. A smattering of history demolishes this notion. Edward Bernays’s pioneering study Propaganda (1928) founded the 20th-century study of public relations. It also became a guidebook for the Nazis in their project of manipulating mass psychology. Bernays was horrified when he learned in 1933 that Joseph Goebbels was using the book when constructing the cult of the Führer, but not surprised. A nephew of Sigmund Freud’s, Bernays never doubted that the findings of rational inquiry could be used for malignant ends.

To enjoy our latest analysis of politics, news and events, in addition to world-class literary and cultural reviews, click here to subscribe to the New Statesman. You'll enjoy all of the New Statesman's online content, ad-free podcasts and invitations to NS events.

More than 30,000 people suffer an out-of-hospital cardiac arrest in the UK each year, and fewer than 1 in 10 survive. It’s why Sky Bet and the British Heart Foundation are asking 270,000 people to learn lifesaving CPR. Join the 100,000 who have already started by clicking RevivR.

6—“I’ve been doing this for years with Radiohead”

A glimpse of life as a rock superstar in the Diary this week, as Colin Greenwood lets us in on touring with Radiohead and Nick Cave. The main difference between the two? The dress code. GM

I’m still struck by the sheer size and scale of the enterprise, of what it takes to put such a big show on the road. Arriving backstage at these enormodomes, you’re faced by a phalanx of shiny black and silver articulated lorries, ferrying tonnes of black boxes that throw out all that weightless sound and light into an arena stacked up to the gods with people who speak and dream in other languages, cultures and lives.

7—“Under no illusions”

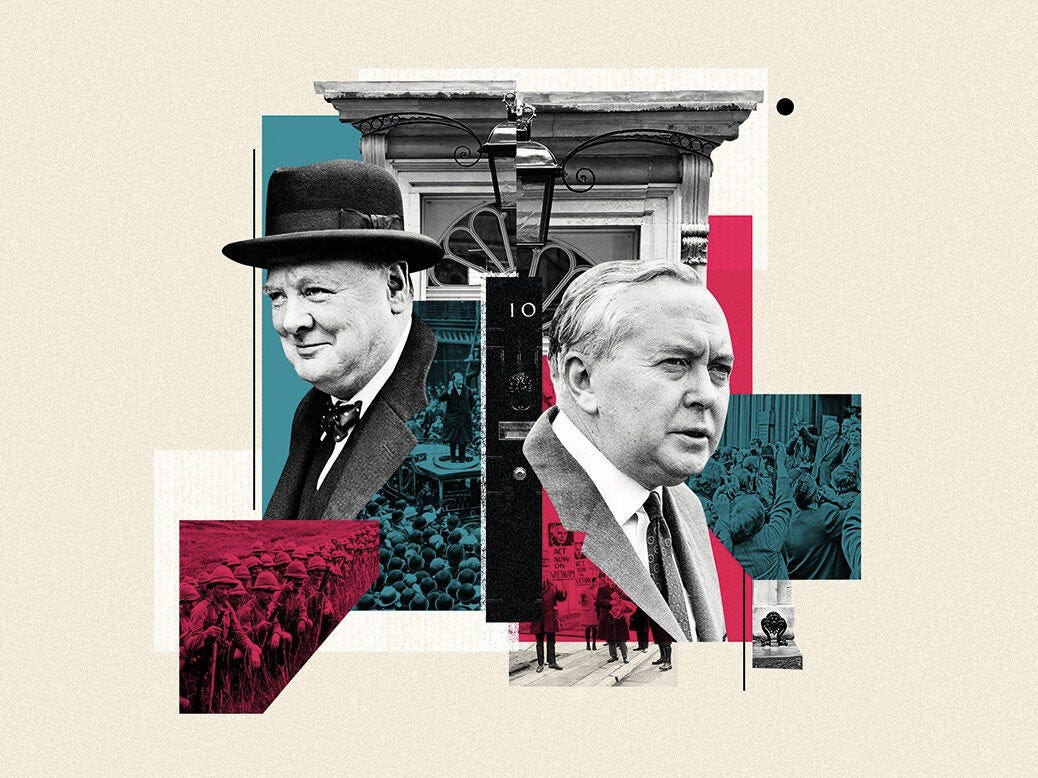

Do we need more lengthy biographies of Harold Wilson and Winston Churchill? Maybe not, but we’ve got them anyway. Simon Heffer critiques the first instalments of a new series of prime ministers’ lives. NH

Peter Caddick-Adams, a highly able military historian, writes on Winston Churchill, and the former Labour politician Alan Johnson on Harold Wilson: both are interesting choices. Their respective works show the strengths and weaknesses of a project such as this; not least that there is sometimes little left to be said about some subjects (as whoever does Thatcher, Lloyd George or Gladstone may find), or that occasionally new material provides a genuine insight… Both these books, in their different ways, show there is nothing new in the nature of politics, and there probably never will be.

8—“Vengeance delivered”

With the death of Yahya Sinwar, Benjamin Netanyahu can claim the scalp of the author of the worst Jewish massacre since the Holocaust. But even so, Rajan Menon writes, the post-7 October circumstances remain the same, from the diplomatic deadlock to the “blasted skyline of Gaza itself”. NH

Israel has a litany of strategic questions to answer about the future of the Strip: its post-war government, the role of the PA, and who in Gaza is willing to cooperate and risk the accusation of traitor. If Israel’s plan is to annex part of Gaza and impose military rule, how long before thousands of vengeful angry young men who have watched their parents and siblings die join a reconstituted Hamas or a new movement that replaces it and takes up arms against Israel? And what of the reconstruction of Gaza, which now resembles a 25-mile-long Dresden?

9— “An act of filial piety”

John le Carré is the greatest spy novelist not just of his generation, but of all time. Now his son Nick Harkaway has resurrected George Smiley, the wily (if self-effacing) intelligence officer, in a new novel, Karla’s Choice. David Sexton finds Harkaway’s rendition a faithful replication of his father’s style, but wonders whether it lacks his father’s depth. FMcR

If Le Carré’s actual novel-writing can be successfully replicated, though, what does this suggest about the quality and originality of his work? And for how long will any human author be needed to produce continuations, when AI is so efficient in producing imitations and derivations? The Booker Prize website currently hosts a piece by Ian Leslie admitting that genre fiction (Simenon, say) can already be readily duplicated, but hoping that the original fiction the Booker seeks to promote – that which questions the very nature of humanity – will always remain beyond large language models such as ChatGPT. Le Carré, who thought the Booker was beneath him and fantasised about the Nobel, was always enraged by suggestions, notably from Salman Rushdie, that his work was no more than genre fiction. Perhaps Nick Harkaway has accidentally, against all intentions, confirmed it.

10—“She’s box-office”

The elimination of James Cleverly from the Tory leadership contest leaves Kemi Badenoch the favourite once again. Her supporters consider the shadow housing secretary “thoughtful” and “fearless”; her detractors, “divisive” and “toxic”. In this revealing profile, Rachel Cunliffe asks: would she be worth the risk for the Conservatives? PB

One ally suggested that, as an original Brexit backer and long-standing voice on the right, Badenoch had the credibility to make up her own mind. They pointed out she was unafraid as trade secretary to confront the right of the party and disappoint Brexiteers over the Retained EU Law Bill. She also kept quiet during the internal Tory row over Sunak’s Rwanda Bill, while Jenrick quit as immigration minister protesting that the legislation wasn’t tough enough. Some Tories are suspicious at how Jenrick – a recent convert to right-wing, Brexit-coded causes (he backed Remain in 2016 and began his career as a One Nation centrist) – has adopted a more ideologically hard-line approach. Others wonder whether he might revert to the centre if elected leader. Nobody wonders that about Kemi Badenoch.

George’s Best of the Rest

Janan Ganesh: The difference between Kamala Harris and Keir Starmer

Penn, Weise: Energy-hungry tech giants turn to nuclear power

Eleanor Hayward: Are weight-loss jabs the answer to the UK’s obesity crisis?

Will Hodgkinson: The curse of fame too young

Amanda Petrusich: Bon Iver is searching for the truth

John Gapper: Sourdough at scale

Adriana Brownlee becomes youngest woman to conquer the 14 peaks

Science makes breakthrough to bringing back extinct Tasmanian tiger. I’m not usually a NIMBY…

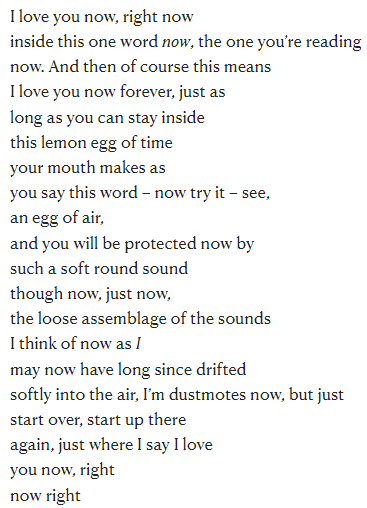

“Now”, a new poem by Margaret Atwood

— Margaret Atwood, © OW Toad Ltd 2024. “Now” is included in “Paper Boat: New and Selected Poems: 1961-2023” (Chatto & Windus)

The New Statesman is home to the finest writing on politics, culture and ideas. To stay up to date, subscribe using the link above.

I am unsubscribing from the New Statesman newsletter because the piece today on Yahya Sinwar was simply an ill-informed repetition of Israeli talking points, not journalism. There is intelligent well-informed criticism to be made of Hamas and Sinwar (listen to Adam Scatz's conversation with Yezid Sayigh on the LRB podcast) but this was certainly not it.

Perhaps unrealistically, I expected a better, more neutral and real analysis of what is happening in Gaza and Israel. That piece was none of the above, therefore in my view not worth my time reading it.