The Saturday Read: 10 pieces for your weekend

Your new guide to the best writing – every Saturday from the New Statesman.

Good morning. Welcome to the second edition of the Saturday Read, the New Statesman’s new guide to the best writing on ideas, politics, books and culture each weekend. I’m Harry, your editor. Will, my co-writer, has again written this week’s sign-off; scroll down for that. (He doesn’t love writing them – “You want to know about my life?” – but we like reading them.) You can let us know what you think of this nascent newsletter by replying to this email.

But first we have a bumper crop of pieces for you this week: ten picks for your weekend, a handful of other NS articles you might like, and links to 15 other stories from across the media. If these pieces intrigue you, why not try a trial subscription to the NS? You can read up to three free articles after registering on the New Statesman website. A digital subscription is just 95p a week. We’d love to welcome you as a reader. Let’s get to it.

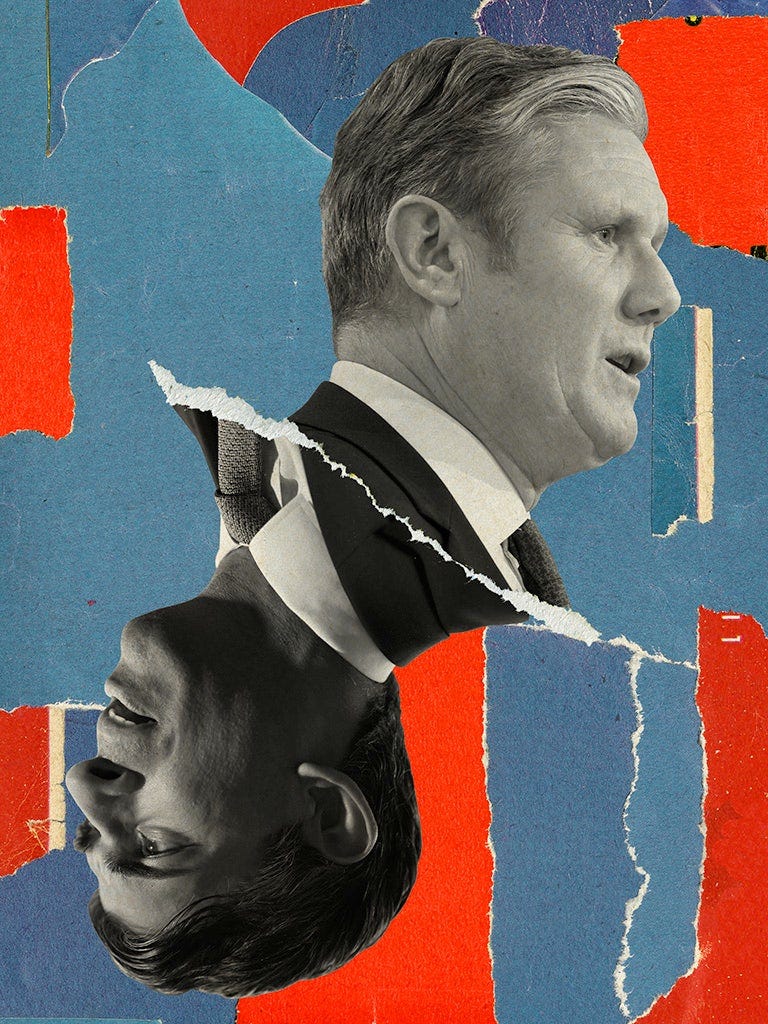

1—“Blithe indifference to uncomfortable realities is the hallmark of Britain’s ruling elites.”

John Gray reacts to Keir Starmer’s recent essay for us. We are, he writes, living under the triumph of corporate newspeak, and Starmer’s proclamations are as vapid as Rishi Sunak’s. Gray also thinks Starmer has moved Labour away from fertile ground: “Terrified of anything remotely reminiscent of the Corbyn era, he has ditched the last vestiges of radicalism on the economy.”

An unreal consensus grips British politics. The cost-of-living crisis and an aborted Brexit have left the government directionless. Strikes across the public sector express a powerful demand for change, not only in pay and conditions but in how the economy works. There is a pervasive sense that the free-market model that guided governments for the past 40-odd years has broken down.

The response of the two main parties is a descent into corporate newspeak. Mimicking the bland tones of CEOs of failing companies, Keir Starmer and Rishi Sunak have each produced lists of five “pledges” and “missions” that are interchangeable in their emptiness. These are not workable policies but public relations exercises of a kind common in the brand of capitalism whose decline their parties are competing to manage.

2—“There are few issues on which mainstream Republicans and Democrats agree, but Ukraine is definitely one of them.”

Bruno Maçães has met Dmytro Kuleba, Ukraine’s foreign minister, for an exclusive Q&A with the New Statesman, online now.

DK: There are some countries which prefer to support Russia and we have to work with them. Relations between countries work the same way as relations between people; if you do not invest in relations, if you do not send messages, make calls, show that you care, invite for lunches, dinners, make presents, have nice conversations over a bottle of wine, then it just doesn’t work.

BM: When some of these countries in the Global South tell you that this war is Europe’s problem, what is your response?

DK: I say, “Guys, you don’t have to sell all this crap to me, you perfectly understand the implications of this war for you.” You can say 100 times this is not your war and therefore you don’t want to take a position, but the next point you will be making will be about the food prices, the pressure [the Russian paramilitary group] Wagner puts on you by simply being present in Central Africa, the issue of fertilisers and many, many other things. Usually this phrase, “This is Europe’s war” is used as an excuse in order not to take a position, and I’m very honest in my reactions to that. I think it’s good to be sincere when you do diplomacy in the 21st century.

3—“This is why I compare Sunak in 2023 with Corbyn in 2019.”

Ben Walker, our resident polling and election supremo, has all the data you need to understand the political announcement of the week: Rishi Sunak’s plan to “STOP THE BOATS”.

Labour’s unwillingness to talk clearly about Brexit sent its supporters elsewhere. It was one of the many reasons for its landslide defeat. Fundamentally, the party failed to talk about the most urgent issue of the hour. It is through this lens that I view Sunak’s “stop the boats” strategy.

Here’s the thing. The median voter does want controls on immigration. The median voter would prefer immigration controls to be tighter rather than looser. They would rather we were tougher on refugees than more open to them. Britain may be in a more liberal position than previously – from 2014 to 2016 Ukip was regarded by voters as having the best policies on immigration – but the underlying sentiment endures: voters want control.

The salience of immigration is also lower than it was previously: it no longer moves as many votes. In the past, immigration was regarded as an important issue by nearly half the country – a larger number than for the NHS and the economy. But as of February this year, immigration was an important issue to just 12 per cent of voters. This isn’t 2010, or 2014 or 2016. So why is the Prime Minister acting as he is?

4—“I kept tapping friends’ shoulders, saying to them, ‘Look! This is my brother.’”

In an affecting essay, Lamorna Ash scrutinises her relationship with her revered half-brother, Simon. After encountering him by chance – on a London bus, late at night – Lamorna is carried away into the dreamy terrain where memory and storytelling meet.

I’ve interviewed him and written about him countless times. He appeared in my juvenile student plays, his experiences alchemised into more absurdist premises – a short-term space mission, something about mermaids. My eagerness to investigate his life felt, and still feels, like a way of making up for all that the younger me missed out on.

Simon lives in a first-floor council flat occupied by more animals than people – four cats and two tanks of tropical fish. He says he’s been a deviant since he was five years old. He was the kid burning matches in the toilet, spraying walls with graffiti. He hated school. He never made any friends. He couldn’t get along with the teachers. Like me, he was afflicted with panic attacks during puberty. He discovered that if he squeezed the soft skin between his thumb and forefinger hard enough, the pain would shock away the panic – for that reason he didn’t need to tell anyone, because he could look after himself now.

5—“The offshore-fuelled property developer known as Donald Trump, you realise, isn’t a uniquely rotten apple but a structural manifestation of what American capitalism really is.”

Why aren’t sanctions on Russia working? Because, Ben Judah explains, “a fairy-tale invisibility cloak is easily at hand” for any Russian company facing restrictions: the anonymous web of kleptocratic shell companies that grease the wheels of Western capitalism.

The same anonymous shell companies that have been used for decades by Western elites, and corporations big and small, to conceal profits and inheritances are now being used to deliver to Russia the chips, components and payments it needs to keep its war going. This gets at the fundamental contradiction of what both Washington and London are in the world. Political elites cast themselves on the one hand as the defenders of the “rules-based international order” of territorial integrity, but are on the other hand the guardians of the global financial secrecy system, an opaque, ungoverned space, enabling kleptocracy, sanctions evasion and illicit finance on a Putin-level scale.

6—“It was the same kind of implosion of the Third Way, which happened at the macro scale, just in my own life, and in my bank balance and in my heart, all at once.”

Sophie McBain meets Mary Harrington. This is the best sort of interview: a thoughtful sceptic testing her subject’s arguments.

The term wasn’t in use then, but if you had met Mary Harrington – the polemical, iconoclastic writer and self-described reactionary feminist – in the early Noughties, you might have described her as woke. She lived in various communes, experimented with drugs, considered her gender and sexuality fluid (briefly changing her name to Sebastian) and co-founded a tech start-up with friends. “We all thought it would be possible to get filthy, stinking rich, and also to pay our taxes, and also to save the world,” she recalled when we met at her home in Bedfordshire, her living room quiet and dimly lit, a Labrador curled dutifully at her feet.

7—“Universities make us more competent but less educated.”

Adrian Pabst has written a coruscating 2,700 words on how British universities lost the plot. You can catch it on the cover of this week’s magazine, or as an audio long read here. Pabst is particularly good on how the managerial takeover of universities has redefined what it means to be an academic – for the worse. If you want another 5,000 words on universities from something closer to the student’s perspective, you might like this piece, from 2019. (Reader, I wrote it.)

As with other areas of public policy, central government cut funding even as it expanded regulatory requirements and the micromanagement of standards in research and teaching.

The central imposition of these standards depresses academics, creates extra layers of bureaucracy and strengthens the managerial class’s hold over universities. Both the Research and the Teaching Excellence Framework (the REF and TEF) are exercises in top-down managerialist auditing, which determine how institutions rank in university league tables and what their share of government research funding, worth £2bn per year, will be.

Yet the rhetoric of academic excellence cannot mask the reality of what our universities actually produce. The claim that most articles published in top-ranked journals represent “world-leading” research (a REF term used as an evaluative criterion) is ludicrous. Such journals are usually owned by global publishers. They share a corporate outlook: excellence is measured by the number of downloads and citations work receives. The quality of the work itself is an afterthought. Excellence becomes little more than a popularity contest judged by managerial metrics.

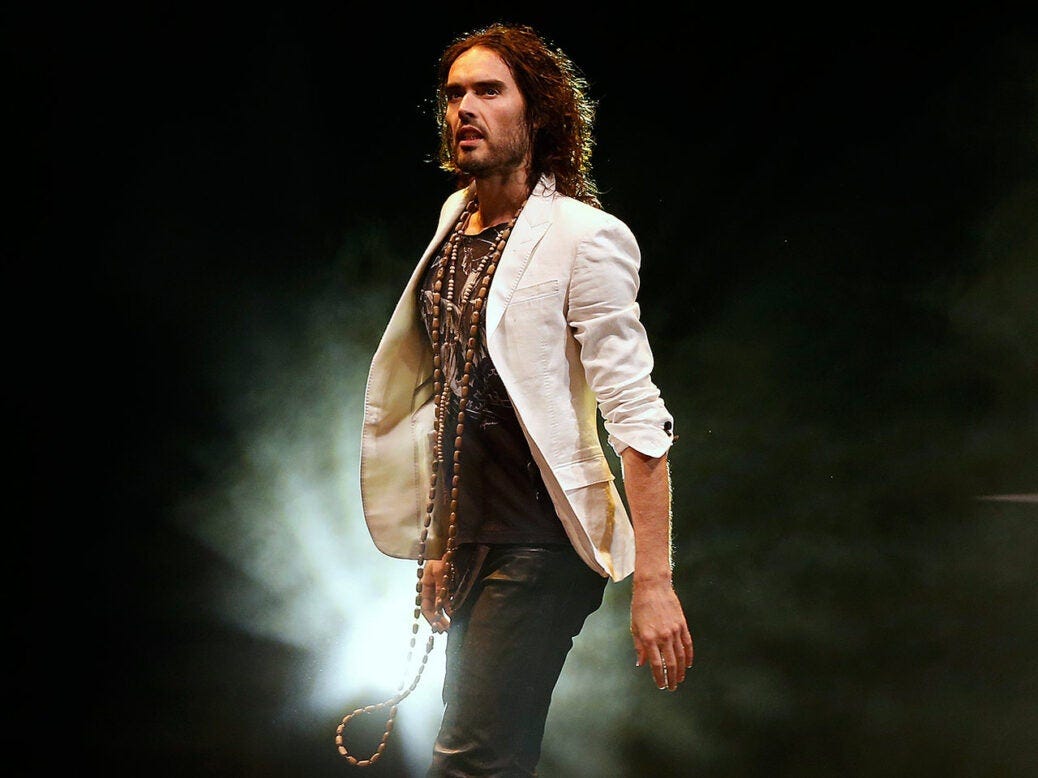

8—“It seems that Russell Brand has been America-brained.”

In this very widely read op-ed, Finn McRedmond charts Russell Brand’s trajectory from cheeky-chappie communist revolutionary to lobotomised American culture-wars hack. As Brand fights these battles from his shed in Oxfordshire, his transformation has been sad to watch.

Perhaps his few years spent living in LA exposed an ugly underbelly of Hollywood that evolved his distrust of the elite. Maybe it is because Brand spends a lot of time on the Anglophone internet on which American cultural norms are hegemonic. Perhaps he is just a cynical iconoclast.

Whatever it is, Brand has internalised assumptions generated by a brand of heterodox American – Joe Rogan, Glenn Greenwald, Tucker Carlson – while clinging on to a veneer of old-fashioned British socialism. But perhaps that tension is not as awkward as it seems. The soul of Corbynism, for example, is the argument that a cabal of elite capitalists have manipulated the system against the everyman. “They’ve stitched up our political system to protect the powerful,” the former Labour leader said in early 2017, “to line the pockets of their friends.” There are few journalists in the United States who talk about the rigged system more than Carlson; it is exactly the mode of politics Brand trades in too.

9—“We need to stop gaslighting women.”

Wes Streeting, the shadow health secretary, has spoken to Rachel Wearmouth, our deputy political editor, about everything from NHS privatisation (“It could not be further from my politics, values or aims”) to the vexed issue of sex and gender.

“You can’t have a situation where a male rapist rapes a woman and then after the event defines as a woman,” Streeting says. “It is an insult to people who are trans who are seeing their identity used as a political football, and it is a danger to women as well.

“I think that the Scottish case provides an opportunity for us to all pause and take stock. I acknowledge that women who have been raising the alarm about this have done so in good faith. We need to stop gaslighting women, stop silencing women and stop pretending that there aren’t challenges, because this male rapist in Scotland has proved that there is a challenge.”

10—“This spring’s prime ministerial activity has a frantic velocity we haven’t really seen since the days of New Labour.”

Writes Andrew Marr in his column this week.

Whereas a Northern Ireland deal was a tilt in the direction of the sensible centre, on small boats Sunak needs to sharpen the difference between the parties. The more centrist outrage, the more liberal bile, the better for Sunak: he needs the applause of those Tories most nervous about his negotiation with the EU.

Resolving the nurses’ strikes, too, will be hard. Under increasing pressure to cut taxes, it’s hard to see where the Treasury is going to find enough money, though I’m told the leeway is greater than advertised. The longer industrial action goes on, the harder it becomes (verging on impossible, actually) to make progress on Sunak’s promise to cut NHS waiting lists.

Elsewhere on the NS

Complement Andrew’s column with this piece from David Gauke, who has the inside track on how Tory MPs have been told that “2023 will be a year to forget”, and why the UK economy may be rebounding more quickly than Sunak would like.

“A BBC journalist, who asked not to be named, backed this assessment, telling me Lineker is an ‘overpaid [presenter] who knows he’s embarrassing the BBC and should shut up’.”

Don’t essentialise politicians based on their background, whatever you think of their policies, argues Anoosh.

Recessions make the rich richer. Will Dunn explains.

“For a philosopher concerned with the future, Marcuse was uniquely bad at predicting it.”

“We’re on the road to a united Ireland – and that’s going to be unstoppable.” Freddie Hayward meets Colum Eastwood, the leader of Northern Ireland’s SDLP.

“If there is a more slippery figure in British journalism, I am yet to come across them.” Iain Dale reflects on the unique reportorial approach of Isabel Oakeshott.

Best of the Rest

Times: Boys think reading is “punishment”. If you were being taught English in a British school you’d feel the same way.

Telegraph: Westminster turns on auto-delete.

WSJ: Musk plots Texas utopia. Future Jonestown just dropped.

Mirror: British increasingly “extracting own teeth” in lieu of NHS dentistry.

Christopher Caldwell: Americans are too comfortable with emergency rule.

James Parker: The freaky genius of Lana Del Rey and Miley Cyrus.

Annie Ernaux: Seduction in the supermarket.

Patricia Lockwood: I actually went “To the Lighthouse”. When will she go to Jacob’s Room?

Annie Lowrey: Middle-class jobs are now low-wage jobs.

Patrick Maguire: Keir Starmer, the accidental Irishman. Maybe the best article ever written about Starmer.

The Nation: Ron DeSantis’s struggle.

Agnes Callard’s marriage. A Rorschach test for how you view adultery.

Sunak’s fave hotel. It’s not a Premier Inn off the side of the M40.

And with that…

I moved house this week for the second time in two months. I’ve perfected lugging things. Three suitcases of books; one trunk of clothes. I’m in Bloomsbury now, after several accidents, and I never intended to end up here.

“Bloomsbury. No, not Bloomsbury,” writes Kingsley Amis in Lucky Jim. By the Fifties, when Amis was writing, the Bloomsbury image – sultry queer aesthetes complaining about servants from their sedan chairs – lacked credit. The immediate postwar spirit was masculine, irreverent, social democratic. Now, after several accidents, our society is as oligarchical in character as it was when the first Bloomsberries had their elegant parties. And all those aesthetes are back in fashion. With any luck, I’ll have some servants soon, and write the next Mrs Dalloway.

Thank you for reading. Don’t miss out – subscribe to the New Statesman and stay up to date with everything you need: from news and analysis to comment and criticism.

Whether you’re looking for a sharp blog or a finely written feature, the New Statesman has you covered. Have a good week, and catch you next Saturday.