Good morning, and welcome to the Saturday Read, the New Statesman’s weekly guide to the best writing on ideas, politics, books and culture. This is Harry, along with Will and Pippa.

Last week we sent you a piece by one of Newsnight’s founding presenters on the programme’s future. Now the BBC has cut 60 per cent of the show’s staff. What has happened here? Programmes are losing their dedicated reporters and will, as one former BBC journalist put it in 2021, be forced to survive on their “dollop of Newsgathering gruel”. This story starts with Emily Maitlis being constrained by BBC bosses in 2020. Now the BBC is in danger of losing “another flash of colour”.

If you are receiving the Saturday Read for the first time, it is our flagship weekend newsletter for subscribers and registered readers. Click here to read online if it cuts off midway. If you already subscribe to the NS, thank you for being a reader of ours. If you don’t yet and these pieces intrigue, perhaps you’d like to try a subscription to the NS. Read three articles after registering. The first month of a digital sub is then free.

1—“I did not expect to see a day when the slaughter of Jews would again be a matter for celebration.”

“I am afraid and furious,” writes Howard Jacobson in one of a number of essays we ran this week addressing the question: how does it feel to be Jewish now? We gathered together several of them in an email to you on Thursday. (“A refugee isn’t a colonist,” writes Jacobson, in an implicit response to Rashid Khalidi.) HL

I am of the left only to the degree that I am not of the right. These are categories that have rarely explained anything to me, other than the fatal inadequacy of all belief systems to the complexity of experience. To cross a busy road, you need to look left and right.

“We won’t ever be forgiven for this,” my then father-in-law said after Israel won the Six-Day War, “the left hates a winner.” He knew about the left. He had been a leftist himself and fought against Franco in Spain. “Even a Jew?” I asked. He patted my golden curls. “Especially a Jew,” he said.

2—“Kissinger specialised in obvious truisms delivered with oracular grandeur.”

Henry Kissinger died this week, out at 100 years old, surrounded by his family, insulated by wealth against reality. How did he make so much money? Ben Judah has a theory. WL

The actual Kissinger genius over the last few decades was not these anodyne comments but the ability to listen – and therefore say exactly what the client, the sponsor or the establishment wanted to hear. This was in sharp contrast to committed public thinkers on geostrategy such as Brzezinski or George F Kennan, who often said what Washington didn’t want to hear. The result was that Kissinger, far from practising what his associates such as the political scientist Graham Allison call “the moral idealism of realism”, had blown with the wind.

3—“This tension – between global markets and the sanctity of British institutions – has bubbled below the surface in the Tory party for a generation.”

Who will buy the Daily Telegraph and the Spectator? Lord Rothermere? Rupert Murdoch? Paul Marshall? The funniest option is increasingly the most likely: the titles will be returned to the Barclay family, in a complex deal powered by Abu Dhabi money. It’s driving some Tories, particularly those who work for the Telegraph, mad. Stephen Glover explains why. WL

Charles Moore, a former editor of both the Daily Telegraph and Spectator, in a recent Telegraph column… inveighed against the “nationalisation” of the paper. He ended: “After more than 40 years’ friendly acquaintance with the readers of all our titles, I feel quite confident in predicting that they would not forgive any government which let them go.” Moore is a figure in the Tory firmament, admittedly closer to Boris Johnson than to Rishi Sunak, but not to be ignored. He was gently threatening the government. It should expect, if it let his old newspaper slip into Sheikh Mansour’s and RedBird IMI’s hands, a Tory revolt.

4—“The book turns out not to be about machines as such.”

Mark O’Connell reviews Robert Skidelsky’s rather blah-blah sounding book, The Machine Age: an Idea, a History, a Warning. He is particularly amusing on Skidelsky’s first few pages. WL

The Machine Age leads the reader, in its early pages, to expect some grand statement about the world and its future. (The title alone lends the enterprise a certain aura of epochal definitiveness.) Before he gets to the main business of the book, Skidelsky provides, in addition to the preface, an introduction and a prologue. There is even a glossary “for the technologically challenged”.

Some of its entries are arguably useful – for Moore’s law, natural language processing etc – but I did find myself wondering whether a person who needs a definition of “the internet” is likely to be reading a book like this in the first place, or any book at all for that matter. This might seem like a paratextual quibble, but it points towards a larger problem with the book: once all the throat-clearing is out of the way, Skidelsky seems to lack clarity on what point he is setting out to make in the first place.

Charging up and drilling down. Whilst today we’re mostly in oil & gas, we’re also working to roll out EV charging hubs and recently opened up the UK’s largest public hub in Birmingham. And, not or – that’s our approach. See how bp is backing Britain.

5—“National mythology can only stretch so far.”

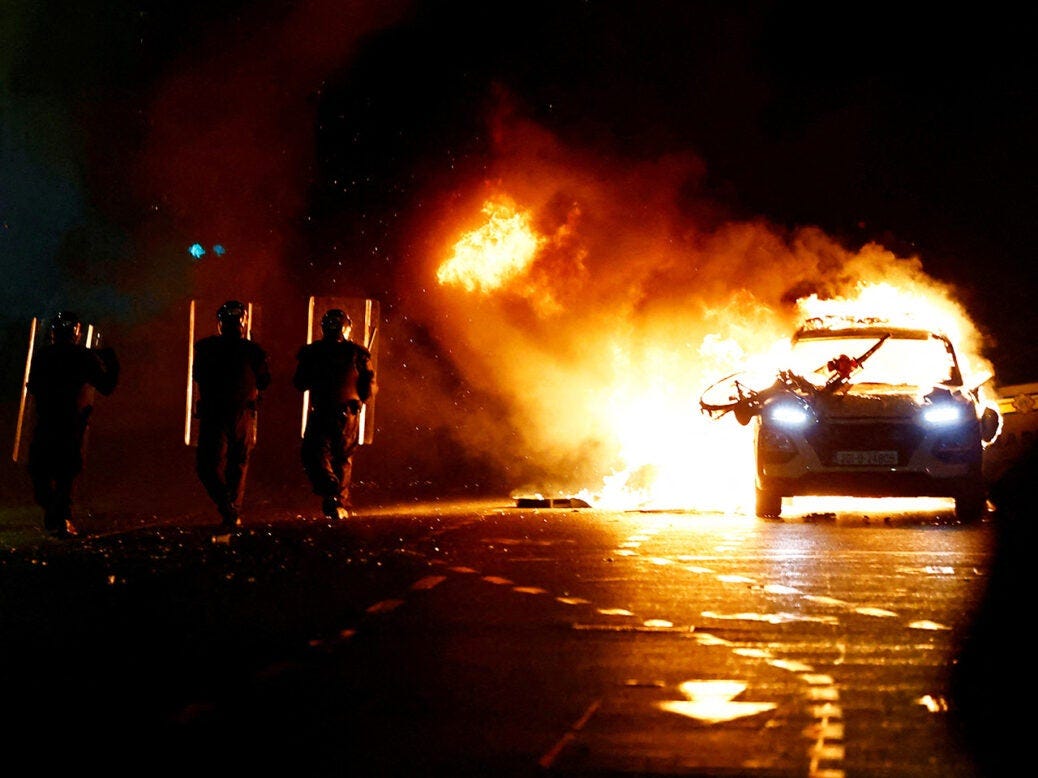

A week on from riots that shook Dublin, Finn McRedmond examines the Irish backlash against migration. WL

On a per capita basis, Ireland has accepted six times more refugees from Ukraine than Britain. A fifth of the country’s five million population was born overseas. One opinion poll conducted in March by the Business Post/Red C, found that 75 per cent of people believed Ireland was accepting too many refugees. The country has long considered itself immune to the worst excesses of national populism but the current levels of immigration, combined with the profound housing crisis, mean Ireland has become a tinderbox.

6—“The politics is not the point.”

James Marriott decreed it the first time “a really bad novel” has won the Booker Prize. Pippa Bailey spoke to Paul Lynch, the writer behind the novel in question: Prophet Song. Has Lynch written a “lame dystopia” or a work of unmistakeable timeliness? HL

Paul Lynch is not a political novelist, and he will “shapeshift” out of any attempt to portray him as one. This was the first thing the Irish writer told me when we met the morning after he won the 2023 Booker Prize for his fifth novel, Prophet Song. “People [say]: you’re a political writer, this is a political novel. I’m, like, no, I’m not a political novelist, my book has far too many layers for that. But it has political significance.”

7—“Where it crosses the line is threats to your family.”

Jason Cowley spoke to Wayne Barnes, the top-flight rugby referee and criminal barrister, about facing awful online abuse, why Big Tech companies should be held to account for what is published on their platforms, and what sport and the law have in common. PB

Barnes is used to being traduced. In his fascinating memoir, Throwing the Book, he describes the different strategies he has used to avoid reading what is said about him. For a period, after a match between France and New Zealand, in which a much-disputed decision by him inflamed All Blacks supporters, Barnes refused to speak to the media for several years; after he joined Twitter, he would not read comments. The problem was that his wife, Polly, was reading everything and internalising the pain. Barnes routinely receives death threats, and vile messages have been directed at Polly and their young children. The most contemptuous are the most cowardly: those who operate anonymous accounts.

8—“Lapland is a prisoner of its own remote geography.”

Megan Gibson takes us to Lapland, Finland’s remote northern region. Home to precious minerals, it is now among the northernmost parts of Nato, bordered by Russia. (If invading Ukraine was foolish, one Muscovite leader has already learned that invading Finland is insanity.) HL

Lapland is home to a bountiful reserve of rare minerals, and foreign mining companies have long vied to set up operations and extract them. A few have been successful: Kevitsa is one of the largest mines in Finland, and Kittilä mine is Europe’s biggest producer of gold. Certain politicians and business groups, both in Helsinki and locally, are determined to see the industry grow and bring more, and much-needed, investment to Lapland.

Best of the Rest will return next week.

Elsewhere on the NS

Andrew Marr reflects on Britain’s luck in being guided by the late Alistair Darling.

The Yale historian Odd Arne Westad writes on the new age of empires.

Sarah Manavis: Elon Musk has more ego than sense. He has quite a few spaceships too. This clip from this week’s DealBook summit is priceless.

“Recollections, to reuse a popular phrase, may vary,” writes Rachel C, who was at the Covid inquiry to hear Matt Hancock’s attempt to portray himself as a beacon of truth and responsibility.

Pravina Rudra asks whether Gen Z is conservative enough to fuel a Tory revival.

Michael Lind makes the realpolitik case for a transatlantic union.

The Mirror editor Alison Phillips writes about being sued by James Dyson (unsuccessfully, as it turned out) in this week’s Diary.

Peter Williams argues that technology will never replace language.

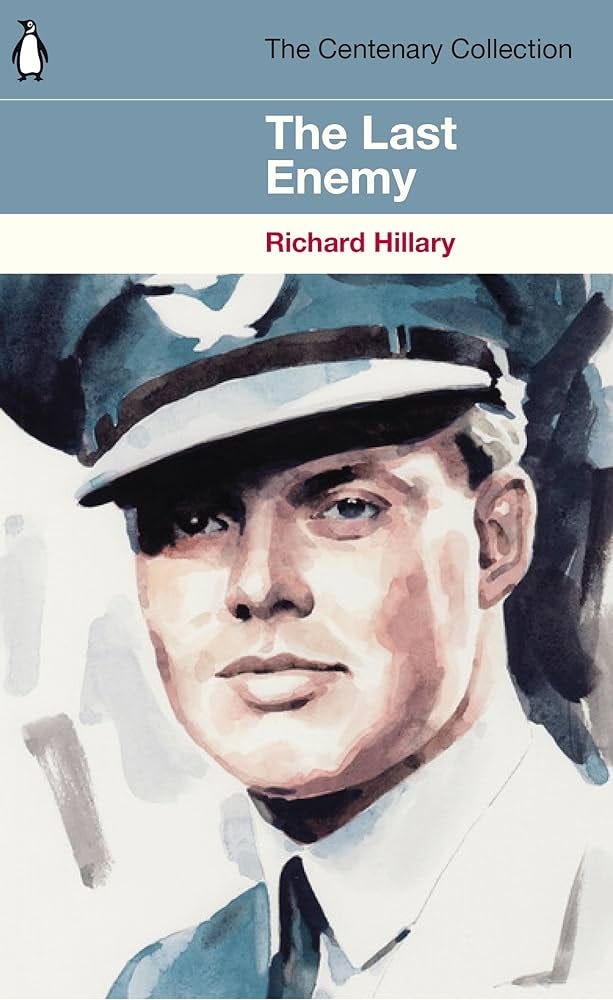

What we’re reading: The Last Enemy by Richard Hilary (1942)

This slim volume, published by an RAF pilot six months before his death in 1943 at the age of 23, will take you back to another world, although one that at times feels eerily familiar:

The seed of self-destruction among the more intellectual members of the University [Oxford] was even more evident. Despising the middle-class society to which they owed their education and position, they attacked it, not with vigour but with an adolescent petulance. They were encouraged in this by their literary idols, by their unquestioning allegiance to Auden, Isherwood, Spender, and Day Lewis. With them they affected a dilettante political leaning to the left. Thus, while refusing to be confined by the limited outlook of their own class, they were regarded with suspicion by the practical exponents of labour as bourgeois, idealistic, pink in their politics and pale-grey in their effectiveness.

They balanced precariously and with irritability between a despised world they had come out of and a despising world they couldn't get into. The result, in both their behaviour and their writing, was an inevitable concentration on self, a turning-in on themselves, a breaking-down and not a building-up. To build demanded enthusiasm, and that one could not tolerate.

Letters of the week

A friend texts, after Thursday’s SR Feature: “Is it Saturday already? Bloody hell I’ve been asleep for 48 hours. Must be time for my smoked salmon and scrambled eggs.”

John Woods responds: “I was brought up in Ireland as a Catholic and developed a love of Israel during my youth, so much so that I offered to spend one of my university summers working on a kibbutz. I then had 30 years of ‘the Troubles’ in Ireland where neighbours murdered each other until a settlement was reached. Throughout all that, the conflict in the Middle East between Jews and Muslims continued. Is there no one who can find a way through this hatred, this fight to the death?”

Perhaps you might like to subscribe to the New Statesman. Stay up to date with everything you need: from news and analysis to comment, criticism and long-reads.

Whether you’re looking for a sharp blog or a finely written feature, the New Statesman has you covered. Have a good week, and catch you next Saturday.

Thanks to Chris Bourn.