Good morning, and welcome to the Saturday Read, the New Statesman’s weekly guide to the best writing on ideas, politics, books and culture. This is Harry, along with Will and Pippa. If you missed our mid-week email, here is a link to the feature we sent out.

If you are receiving the Saturday Read for the first time, it is our flagship weekend newsletter for subscribers and registered readers. You can click to unsubscribe at the end of this email. And click here to read online if this message cuts off midway.

If you already subscribe to the NS, thank you for being a reader of ours. If you don’t yet subscribe and these pieces intrigue, perhaps you’d like to try a subscription to the NS. Read three articles after registering. The first month of a digital sub is then free.

1—“Slowly but inexorably, the US has modified its position on Taiwan.”

Bruno Maçães reports from Taiwan, where he met the country’s foreign minister and watched its National Day parade in Taipei. Is the country facing an inevitable invasion by China, as officials in Washington increasingly assume?

The tension Taiwan faces is this: its navy and air force would struggle to survive the first night of China’s invasion, and its army is entirely untested. To have any hope of resisting China it will need the US to defend it in the water and the air, and the Taiwanese people will need to fight to the end on land. It is far from clear that either of these things would happen if Xi Jinping did invade. HL

Wu told me he recognises China is a threat, but he is reassured by the fact that a conflict over Taiwan would paralyse the global economy. “Any kind of military threat against Taiwan or any kind of blockade will have global consequences,” he told me. Those consequences, particularly the disruption to supply chains, could effectively act as a shield for Taiwan. He was not arguing that economic interdependence will prevent a Chinese invasion. His point was that interdependence will force countries such as the United States to do their utmost to prevent a conflict over Taiwan. It seemed to follow that Taiwan is against a decoupling of the world’s two largest economies, but when pressed, the minister refrained from saying it.

2—“The destruction was as bad as in Aleppo after Russian planes and Bashar al-Assad’s regime had finished with it.”

Jeremy Bowen, the BBC’s international editor, reports for us from Gaza and Israel. Are we witnessing a second Nakba? HL

Dead Hamas gunmen lay where they had been killed, blackened and stinking, swelling in the hot October sun. The mood in Israel, Burg assessed, was something like the years 1945-48. Palestinians have also been transported back to 1948, to the defeat and exile that defines their history, which they call the Nakba – the catastrophe. As Israel won its war for independence, more than 700,000 Palestinians fled or were driven from their homes at gunpoint. The new state took their property and never let them return.

3—“This year, the detached discomfort of the diasporan has felt particularly acute.”

Being part of a diaspora this year, whether Israeli, Palestinian, Ukrainian, or Armenian, meant watching the land of your ancestors disintegrate. Anoosh Chakelian explains how all that guilt and helplessness really feels. WL

The feelings of those who live at a remove from our family history are more complex than any reductive ideological binaries drawn by, say, a British home secretary yearning to prove that “multiculturalism has failed”. It is hard to watch our ancestral lands fragment precisely because our identity clings to fragments: songs and recipes we learned growing up, pointing out places on maps to our English friends. It’s the treacly crust around the lid of pomegranate molasses in my kitchen cupboard; the jagged gold “A” – the first letter I learned in the Armenian alphabet – I wear around my neck every day.

4—“These enemies of the West are more formidable and nihilistic than the old Soviet Union or Mao Zedong’s China.”

A new binary of opposing powers is carving up the world, argues Robert Kaplan. On one side, revisionist powers such as Russia, China and Iran are expanding. On the other, an embattled West is committed to propping up a trembling status quo. WL

In all of this, we in the West should be careful how we label our own side. It is not the world of democracies, not only because something such as anti-Semitism has, as it has always done, rooted itself inside democracies, but because our own side also includes conservative and reactionary autocracies in the Arabian Gulf, Jordan, Egypt and elsewhere – all of which stand for the regional status quo and oppose regime changes throughout the region. In fact, this is a bipolar struggle between status quo powers and movements who want to topple the existing post-Cold War order, whether by territorial acquisition such as Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, or like China’s possible attempt in the future to integrate Taiwan, or by the eradication of an entire people – the goal of Iran’s coalition regarding Israel. Order versus disorder. That is what this still-emerging world conflict is finally about.

Charging up and drilling down. Whilst today we’re mostly in oil & gas, we’re also working to roll out EV charging hubs and recently opened up the UK’s largest public hub in Birmingham. And, not or – that’s our approach. See how bp is backing Britain.

5—“Let them govern, please, with at least a little poetry.”

Andrew suggested in a recent video that Labour must rejoin the single market and tax wealth (I can get behind that). Now, looking ahead, he suggests the party must offer hope. If all Keir Starmer’s party promises is a second age of austerity, voters will soon abandon it. I think that’s right. HL

Roy Jenkins compared Tony Blair in 1997 to a man carrying a priceless Ming vase across a highly polished floor. Well, for Starmer the floor is not only polished but iced; and the vase is twice as heavy, with a hairline crack at the neck. This feat requires the political equivalent of a top-flight athlete’s focus and nervelessness. The frustration about Starmer and Rachel Reeves in Downing Street is gratifyingly real.

But Labour’s success has come, inevitably, at a price. It isn’t possible to both focus on being austerely responsible with the nation’s finances and simultaneously turn people’s attention towards an optimistic and expansive politics. It isn’t possible to both promise to crush migration levels, smash the people-smuggling gangs, and crack down on street disorder, while simultaneously being a movement of cheerful liberal buoyancy. These are choices. It’s like trying to grimace and grin at the same time.

6—“He became my father, husband, and very nearly God.”

Ahead of the release of Sofia Coppola’s biopic Priscilla, Tanya Gold considers how Elvis Presley groomed the teenage Priscilla Beaulieu (his future wife was 14 to Elvis’s 24 when they met) and the erotic cult that clawed at the King, even as he was dying. PB

The marriage was an act of control, narcissism – he made her look like him, with porcelain veneers on her teeth and black dye in her hair – and hope. Priscilla is potentially a saviour, though he won’t be saved, and they lived in that necrotic, speechless space. No wonder it’s a dull film: neither can tell the truth, and so they re-enact a 1950s marriage a decade too late. She took a part-time modelling job. Elvis couldn’t approve: “It’s either me or a career, baby. Because when I call you, I need you to be there.”

7—“The more we treat the internet like gravity, the less we know which way is up.”

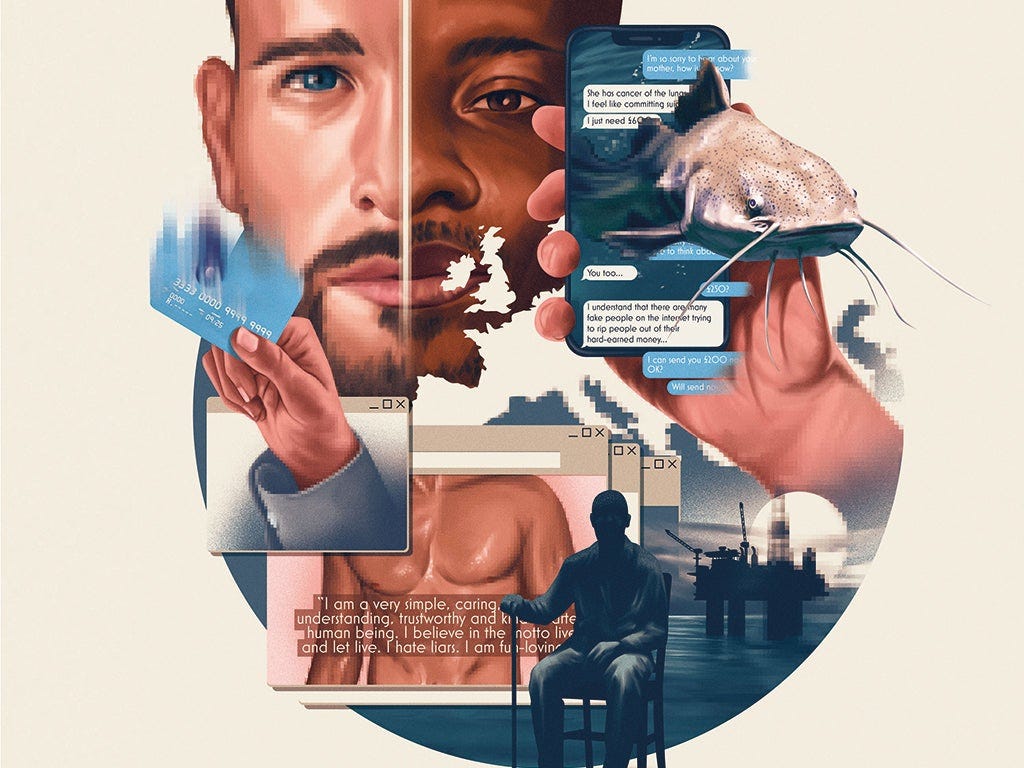

A fascinating and disturbing long read by Stuart McGurk about a vast network of catfishers who conned thousands of pounds out of the lonely online, the detective who catches them, and the way AI is changing romance fraud. PB

The documents related mostly to one identity: a Swedish man in his mid-twenties, sometimes called Alan Baldwin and sometimes called Luke James, who worked in a nursing home. There were photographs of funerals, death certificates, boarding passes, inheritance documents. A Notes document recorded a dating app profile: “I am a very simple, caring, talented, understanding, trustworthy and kind-hearted human being. I believe in the motto live and let live. I hate liars. I am fun-loving…” Written beneath it was a list of 14 dating sites: Gaydar.co.uk, Manhunt.com, Daddyhunt.com, Silverdaddies.com…

8—“We are trying to achieve something superhuman.”

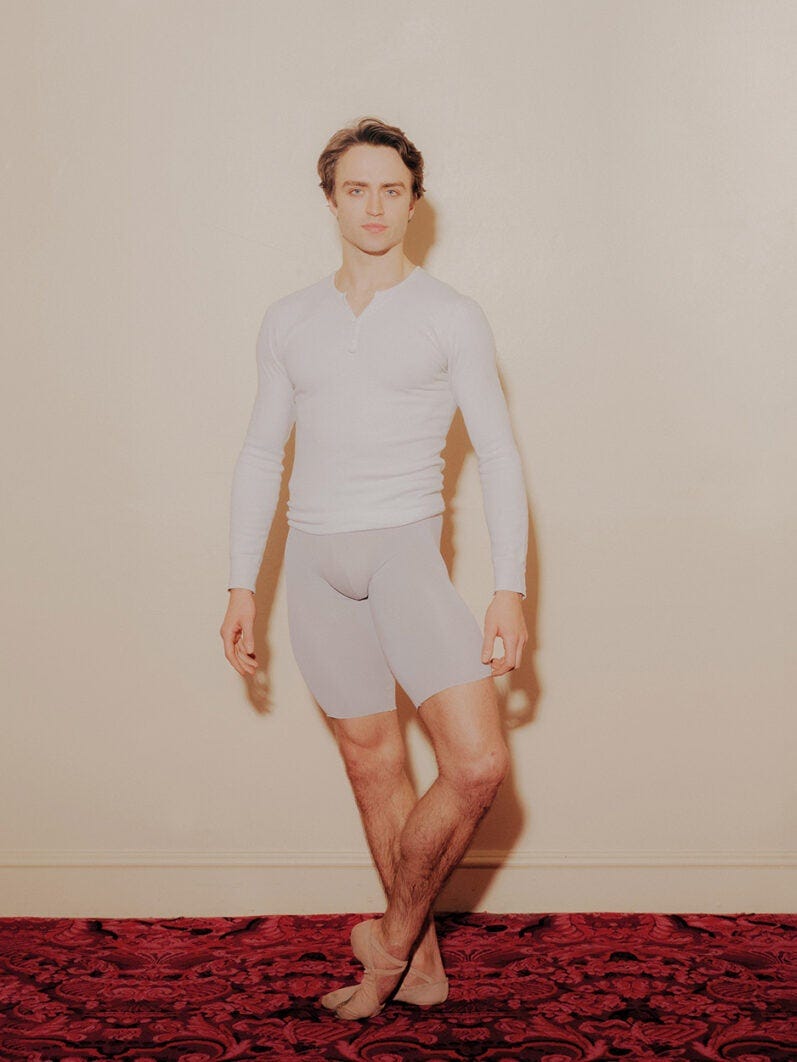

The Royal Ballet principal Matthew Ball talks to Kate Mossman about enduring pain, ballet in the wake of the #MeToo movement, and how Billy Elliot changed his life. PB

Dancers have their own version of the stock flying dream, in which they find they can pirouette forever. They also have a version of the classic anxiety dream, like the one where you have to take your history A-level having not studied history for 30 years: being told to go on stage to replace the lead with five minutes’ notice, not knowing the part. Ball lived out this nightmare (though he did know the part, just) in 2018 when he was recalled from home during the interval to take the lead in Giselle. His performance earned a standing ovation, and he was made a principal within weeks.

9—“I told myself, ‘Write it as if all your family were dead.’”

Writers often rebel against their upbringings, don’t they? Or is that just the conventional wisdom? Julian Barnes considers the dilemma of the artist and their family. WL

A father doesn’t have to be tyrannical, or a mother over-protective, for them to want things to stay the same, and for the child not to grow up – or not in such a way that he or she becomes a writer. A poet friend of mine had a money-man father who was puzzled by his choice of “career”. “The thing is, son, you’ve got to have something to aim for. What are you aiming for?” “Nobel Prize, Dad,” replied my friend, an answer which was strangely judged satisfactory.

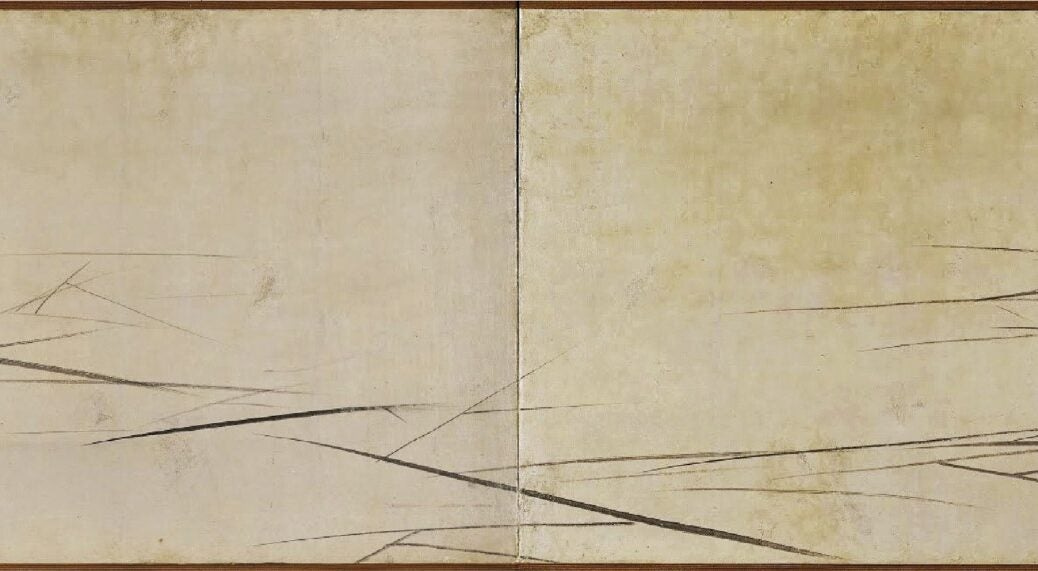

10—”Here is winter – palpable, silent, atmospheric, poetic, and dangerous too – summoned in just a couple of dozen strokes of the brush.”

Any piece that invokes Kazuo Ishiguro’s masterpiece has me at the headline. Michael Prodger, our art critic, writes on Maruyama Ōkyo: artist of the frozen world. HL

In 1639, in a panicky response to fears of cultural domination and the rise of Christianity, which had been spread by Spanish and Portuguese missionaries, Japan threw out the foreigners and suppressed their religion. The only Europeans allowed to remain were a colony of Dutch traders, confined to an island off Nagasaki to keep the taint of the West away.

This isolationist strategy was largely successful. However, some Western influences did slip through, including Dutch paintings and prints that made it across to the mainland. It was through these that the Japanese ukiyo-e (“pictures of the floating world”) artists first came into contact with the idea of vanishing-point perspective. This way of depicting receding space had been common in European art since the 15th century but was unfamiliar to artists whose painterly traditions ultimately derived from China. Gradually, ukiyo-e artists, who specialised in woodblock prints, began to experiment with the technique and apply it to their images of the refined cultural world of Edo (Tokyo): the prints became known as uki-e (“floating pictures”).

If you are an NS subscriber, perhaps you would like to give the gift of an NS subscription this Christmas. It is both priceless and quite specifically – affordably – priced.

Elsewhere on the NS

Jeanette Winterson writes the Diary for our Christmas special.

David Sexton misses the nastiness of Roald Dahl in the too-sweet Wonka.

Katherine Rundell, author of Waterstones’ book of the year, on why children need stories now more than ever.

Pippa Bailey on her personal reckoning with charismatic Christianity.

“A new social character is emerging in modern Western societies: the libertarian-authoritarian personality – a dark by-product of late modernity.” This is a splendid original essay from Oliver Nachtwey and Carolin Amlinger.

Is today’s reactionary right “fascist”? Oliver Eagleton suggests that term may not be the best way to think about this movement.

Matthew Engel goes undercover as a council candidate.

John Gray on Werner Herzog: don’t miss.

Jeremy Cliffe deploys Joseph Roth’s The Radetzky March (1932) to explain Russia’s non-dissolution. It’s a fascinating piece, although I’m not sure “Putin’s invasion remains a debacle” – his troops hold almost a fifth of Ukraine.

Ed Smith is, as ever, the man to read on English cricket and elite sport.

Sophie McBain reviews a “bonkers” new study by a British Lacanian.

Perhaps you might like to subscribe to the New Statesman. Stay up to date with everything you need: from news and analysis to comment, criticism and long-reads.

Whether you’re looking for a sharp blog or a finely written feature, the New Statesman has you covered. Have a good week, and catch you next Saturday.

Thanks to Chris Bourn.

Fantastic piece introducing me to Maruyama Okyo

I was going to say the same thing... Best of the Rest missing :(