The Saturday Read: Age of innocence

Inside: JFK, Bill Gates, female chancellors, tax traps, the Booker, and Dostoevsky.

Good morning, and welcome to the Saturday Read, the New Statesman’s weekly guide to the best writing on ideas, politics, books and culture. This is Harry, along with Pippa and the other Will. Will is somewhere even colder than London this week.

If you are receiving the Saturday Read for the first time, it is our flagship weekend newsletter for subscribers and registered readers. Click here to read online if it cuts off midway. If these pieces intrigue, perhaps you’d like to try a subscription to the NS. Read three articles after registering. The first month of a digital subscription is then free. And if you already subscribe to the NS, thank you for being a reader of ours.

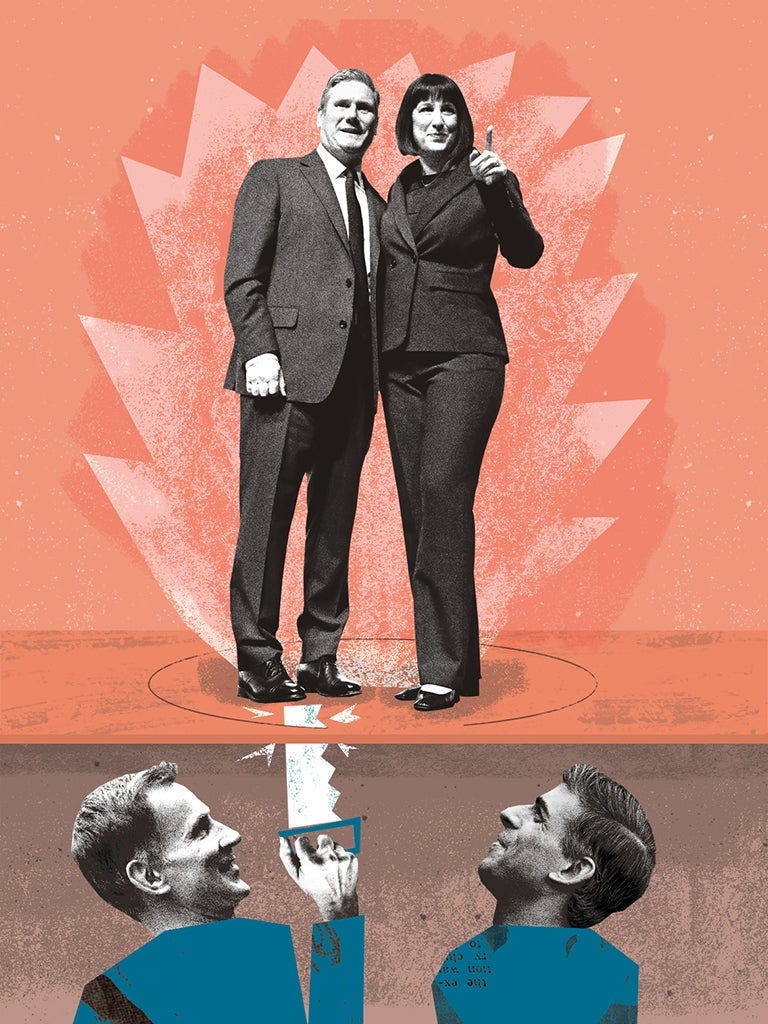

1—“Are Hunt and Rishi Sunak making long-term decisions for the good of the country, or are they planning for chaos?”

The Autumn Statement was designed to make life difficult – for Labour. Jeremy Hunt’s tax cuts, announced this week, will have to be paid for by a level of austerity that would make George Osborne blush. (We need fundamental tax reform.) WD

Hunt had two options. He could have been clear that we do not know how much we will have to spend on debt interest, and that we do not really know how much fiscal headroom there is, if any. A genuinely conservative policy would have been to accept that, and to concentrate on ensuring that the UK’s debt begins to fall earlier. But for Hunt this would have come with the risk that the headroom might become real, years into the future, giving Rachel Reeves an easier job.

His other option was to spend the money now, even though it might not exist – at the risk that the country might have even higher debt costs later, and therefore impose on Reeves an even greater requirement to raise taxes or cut services (or both). The first option was conservative economics, the second was Conservative politics. Obviously he chose politics.

2—“Ministers have swapped EU workers for non-EU workers from India, Pakistan, Nigeria and elsewhere.”

This week’s immigration figures showed nearly 750,000 new net arrivals, driven chiefly by non-EU migrants. This is the truth of Brexit, writes Anoosh: the government now uses immigrant workers to fix Britain’s ailing labour markets. WD

No matter how much they orate about bringing Britain back to work, the Tories’ secret workforce is drawn from abroad. Vote Leave would argue this is “taking back control”, as the slogan had it. There is, after all, more control in our immigration system than there was under EU freedom of movement. It’s just the state is using that control to bring in more people than before. Under the post-Brexit points system, the government can essentially decide which jobs it needs to fill and add them to the shortage occupation list.

3—“The assassination is said to have destroyed an age of innocence.”

Sixty years after the death of John F Kennedy, writes Phil Tinline in our cover this week, “the shots that rung out around the world on 22 November 1963 still echo through American politics”. Tinline thinks the moment created two myths that still capture the American mind. PB

The true believers in Dallas took one of those stories inaugurated by the assassination – the president as saviour – to its literalist extreme. Robert Kennedy Jr’s campaign does something similar for the other narrative: the one that claims shadowy forces control everything. By the end of the 1960s, many believed that Kennedy had been killed by malignant forces inside the state itself, to prevent him from reaching a settlement with the Soviets over Cuba, or ending the war in Vietnam, or – why not? – achieving world peace.

One theory, dramatised in Oliver Stone’s 1991 movie JFK, contended that the murder was the work of the “military-industrial complex”. Others blamed the CIA, or the FBI. There was plenty that these organisations could justly be charged with, but claims of vast conspiracy go beyond that, to conjure a vision of true American power as perfectly organised, invisible and omnipotent.

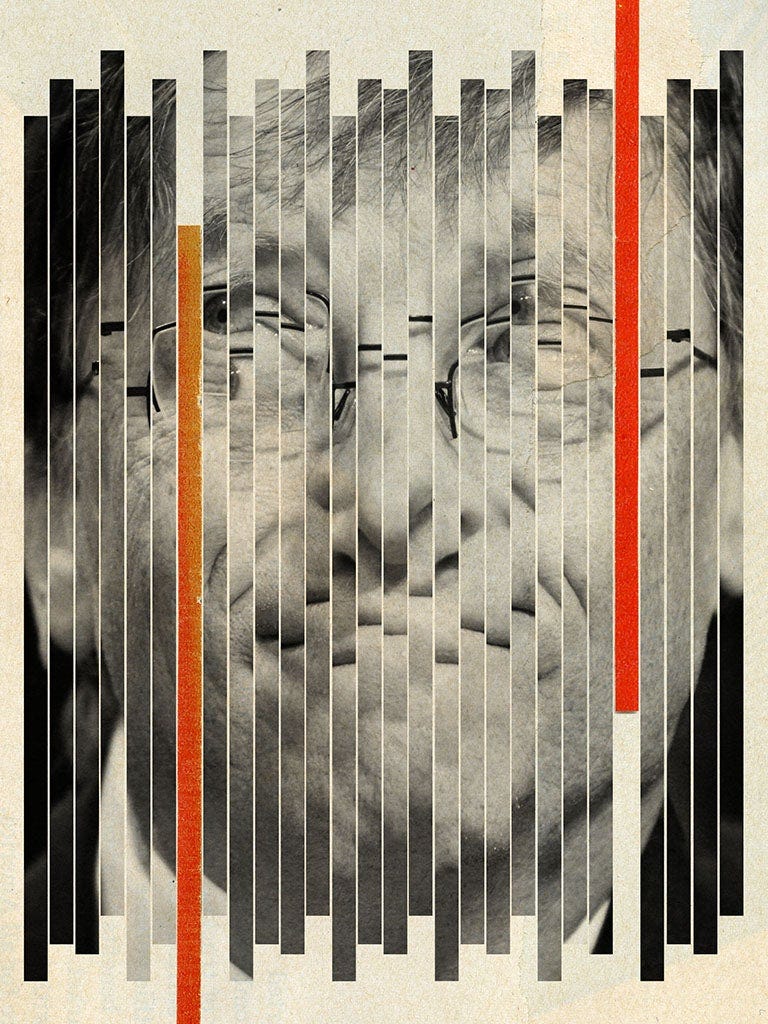

4—“Human lives have to be more than notches on a plutocrat’s bat.”

Bill Gates is a totemic figure in the minds of conspiracy theorists, who imagine his enthusiasm for vaccine programmes has a darker motive. The thing is, argues Quinn Slobodian in his review of Tim Schwab’s The Bill Gates Problem, the tin-foil crowd have a (bit of a) point: rather than paying plenty of tax and allowing the state to do good, he wants to do the good himself, and his means are often questionable. WD

The easiest way to get into the pantheon is to build one of your own. Like many rich people, Gates fancies himself a polymath because there is always an employee around to admire his new titbit of learning. His masterstroke was to transform an entire media ecosystem into an army of yes people. A broad swath of what is usually considered the centre-left wing of global journalism– such as the BBC, the Financial Times, the Guardian, the Atlantic, the New York Times, Le Monde, Der Spiegel and Al Jazeera – is funded by money from the Gates Foundation. Time and again, Schwab gives examples of those outlets soft-pedalling criticism of Gates’s philanthropy.

bp is working to bring more lower carbon energy to the UK and keeping oil & gas flowing to help meet today’s energy needs. And, not or – that’s our approach. See how bp is backing Britain.

5—“Before it was respectable, economics was a substantially female activity.”

Emma Rothschild, the Harvard professor of economic history, read Rachel Reeves’ The Women Who Made Modern Economics and – aside from all that copy and pasting – found it to be rather good. PB

There is a question, in the end, that is implicit in Reeves’s evocation of the eminent women economists and policymakers who have had a distinctively empirical way of thinking: is there something unabstract about the economic thought of women? Or is this no more than the outcome of the institutional circumstances of the economics profession, in which the opportunities for making one’s living by being abstract – as a professor in a large university, for example – have been almost entirely opportunities for men, the recent Nobel prizes notwithstanding?

6—“She learned how to play the game.”

Rachel Cunliffe profiles Claire Coutinho, the secretary of state for energy. Could Coutinho, a favourite of the increasingly unpopular Rishi Sunak, be the next Tory chancellor – before the next election? PB

“Different wings of the party would all think she’s one of them,” a fellow MP told me, adding she was “not easily boxed”. One-nation centrists can point to Coutinho’s social justice credentials and environmental work; the right to her championing of the government’s Higher Education Freedom of Speech Act, legislation designed to combat cancel culture at universities. The conservative philosopher Roger Scruton is one of her political heroes, but in today’s “vibes-based” politics, Coutinho gets cast with liberal Tories. She entered parliament as a Johnson Brexiteer, was promoted by Truss, and now stands as Sunak’s right-hand woman. This ability to quietly adapt, without accusations of inauthenticity, is a valuable skill for anyone looking beyond the next election.

7—“Anyone but the Yanks!”

Finn McRedmond breaks down the Booker Prize’s long spiral into irrelevance. HL

The Booker, like any cultural machine, is vulnerable to the throes of politics. Emily Wilson, who judged the prize in 2020, later told the Guardian, “It’s actually OK, if multiple books are good, to think we might want to longlist more by young people and more by people of colour.” A worthy mission, perhaps, and certainly a well-intentioned one. But youth and ethnicity are hardly relevant criteria for selecting the best work of fiction published in a year. Total puritanism may be impossible, but a good panel should attempt at least to limit their judgement to aesthetic merit.

8—“The fatal conceit of the progressive mind is the belief that once the influence of repressive traditions is removed, all of humankind will share its values.”

John Gray weighs in on the Israel-Gaza conflict, and the contorted position in which many progressives find themselves, knowingly or not. HL

There is a certain logic in progressives allying themselves with Islamist movements. In their support for universal human rights they are prototypical liberals; but since they believe Western power lies behind injustice everywhere they feel bound to overlook atrocities committed by Islamists, who reject human rights tout court. The West is not killing itself, as conservatives sometimes say. That would require a degree of self-awareness of which there is no sign. As in the fable of the scorpion and the frog, Western progressives cannot help poisoning their host.

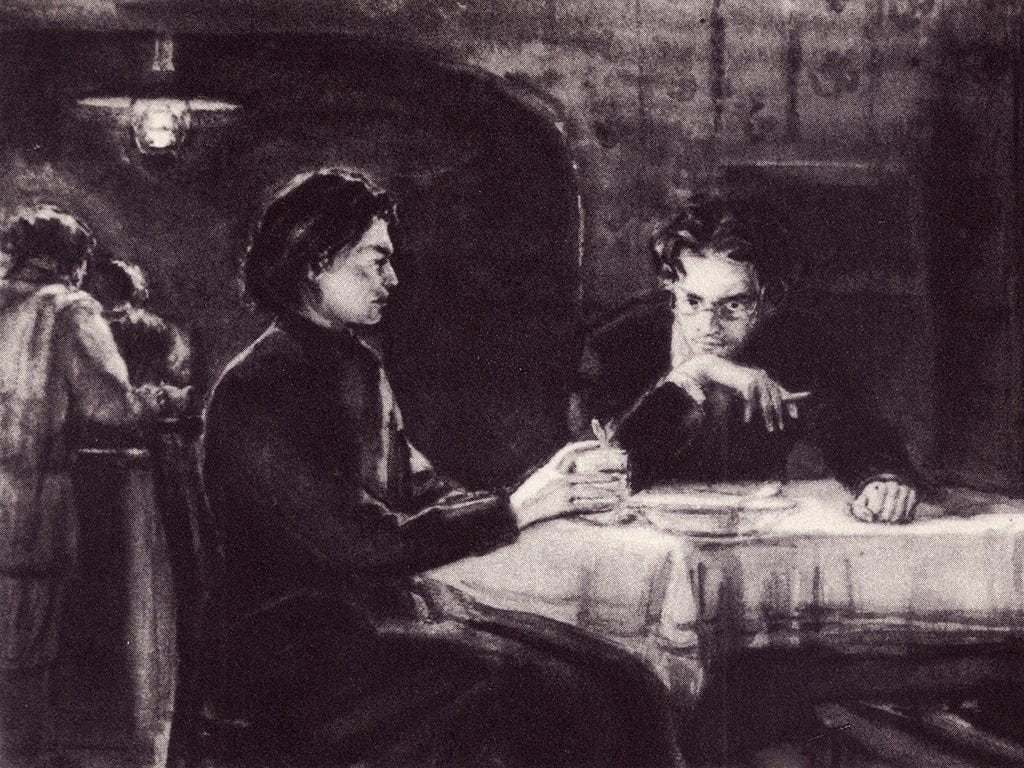

9—“One can’t help but wonder whether, had been alive, he’d have been cheering on fascism’s rise.”

Sam Earle, one of our finer essayists, takes on Dostoevsky, the Brothers Karamazov, and the strange, sonorous tale of the Grand Inquisitor. HL

The Brothers Karamazov also contains flashes of Dostoevsky’s messianic nationalism and virulent anti-Semitism, both of which hardened towards the end of his life. In one egregious passage, Liza, who is 14 years old, asks Alyosha whether it is true “that at Passover the Yids steal and slaughter children?” Alyosha, beacon of life and empathy, can only reply: “I don’t know.”

The young girl then reveals that she has been reading about “some trial” concerning “a Yid who took a four-year-old child and cut off the fingers from both his little hands, and then crucified him”. Here the book’s moral refrain – why do innocent children suffer? – is effectively pinned on the Jewish people. It is only the most glaring of several passing swipes. Zosima’s message of compassion and empathy only stretches so far.

Best of the Rest

On war rations in Will’s absence.

Reuters: 24 hostages released by Hamas in temporary Gaza truce.

Atlantic: Have you listened lately to what Trump is saying? It ain’t good.

Compact: The influencer-journalist.

The Critic: Britain’s Rush Limbaugh.

Liza Mundy: The women who saw 9/11 coming.

Boris Johnson: Here’s how to fix the immigration system I created.

Peter Hitchens: Why I work bank holidays.

Elsewhere on the NS

Is Nikki Haley a threat to Donald Trump? Katie Stallard has answers.

Brendan Simms writes on the global surge in anti-Semitism.

Charlotte Stroud has written a marble-smooth piece on the hard truths of AS Byatt, the modernist who clung fast to realism during a time of faddish post-structuralism.

One of Newsnight’s founding presenters wrote a fine piece for us recently on the programme, which may be facing closure. It doubles as a piece on leadership in media, and how often it is absent. John Tusa explains the two journalistic practices that once divided the BBC. The “Puritans of News” believed in the primacy of “the fact”. For the “Cavaliers of Current Affairs” a fact was simply the start of the story. (In today’s BBC, newsgathering has won.)

TikTok has unearthed Osama bin Laden’s 2002 “Letter to America”.

Sohrab Ahmari on why the election of Javier Milei has caused him to rethink his long-standing defence of populists.

Lola Seaton delves into how we create meaning for ourselves through sport.

“The Dutch have voted for one of the most extreme policy platforms in Europe, but they may not get it.” Ben Coates writes on Geert Wilders’s shock victory.

NB: You can now follow us on WhatsApp. Turn on notifications to stay up to date.

And with that…

The great 20th-century American composer/conductor Leonard Bernstein has had something of a Hollywood renaissance of late. First his West Side Story was re-adapted by Steven Spielberg, then his tutelage of the fictional Lydia Tár became canon. Now Bradley Cooper plays the mercurial Bernstein in the award-chasing biopic Maestro (also his second outing as a director, following A Star Is Born).

The film starts in November 1943 with Bernstein receiving a phone call that will change his life: he is to make a last-minute debut conducting the New York Philharmonic. In one unbroken shot we soar with Cooper’s Bernstein from the bedroom to the theatre – his two great stages. The question the film asks is whether he was at heart a composer – introverted, alone, with a grand inner life – or a conductor – extroverted, a performer, with a grand outer life? Despite his long marriage to a woman, Felicia Montealegre (Carey Mulligan), he also had a number of affairs with men. “I love too much,” he shrugs, “what can I say?”

Thankfully, as I am tired of films about men whose cruelty we forgive on account of their brilliance, Maestro is Mulligan’s film; she is its heart. The poise with which she holds sweetness, sacrifice, denial, love and rage within herself is exquisite.

Today’s title should really be a reference to the great novel. A piece to come.

Perhaps you might even like to subscribe to the New Statesman. Stay up to date with everything you need: from news and analysis to comment, criticism and long-reads.

Whether you’re looking for a sharp blog or a finely written feature, the New Statesman has you covered. Have a good week, and catch you next Saturday.

Thanks to Chris Bourn.