The Saturday Read: All the world’s a page

Inside: The Trump II vision, Frank Auerbach, Bob Dylan, John Gray, the history of Zionism, the Booker Prize, and the New Statesman’s books of the year.

Good morning. Welcome to the Saturday Read, the New Statesman’s guide to politics, culture, books, and ideas. This is Jason, together with Finn, Nicholas, Pippa and George.

Reading my colleague Nick Harris’s fine profile of Samantha Harvey, whose novel Orbital this week won the 2024 Booker Prize, I began to think about my own experiences as a Booker judge in an era when the contemporary literary novel seemed central to the culture rather than merely peripheral to it, as it is today. The Booker Prize used to be a national event, the annual award dinner at the Guildhall in London broadcast live on BBC television and the judging process obsessively followed by the newspapers as they pursued leaks, reports of feuds among the judges and what Saul Bellow called “event glamour”. (Back then the longlist was not published but was invariably leaked by Martyn Goff, a charming literary London fixer and éminence grise of the prize.) The whole thing was an amusing jamboree, not to be taken too seriously. But it still mattered.

I was a judge in 1997, when I was working as a feature writer on the Times. It was the pre-digital age: we did not have access to the internet in the office, or email. That same year I interviewed Martin Amis at his grand house near Regent’s Park. We chatted for several hours over a couple of glasses of white wine in his upstairs study; a postcard from John Travolta thanking Amis for a recent profile he’d published on the actor in Tina Brown’s New Yorker was displayed prominently on the desk.

Amis told me that his mission as a novelist was to go in search of “all the new rhythms”. What did he mean by that? “The task of the novelist is to interpret the present and the near future, to ask where are we heading, how are we changing?” he said. “I knew from an early age that I wanted to write about everyday life; that I wouldn’t write, say, westerns or historical works.”

That seemed right to me then. I was already irritated that so many of the entries I’d been reading as a Booker judge were historical or works of pastiche. Where was the ambition to document contemporary reality in all its urgent complexity, I wondered, the desire to show us who we are and how we were living? Why not be here now, as Oasis put it.

That was a long time ago. As I travel in and out of London most days, looking at people looking at their phones or watching video clips or movies, I am struck by the total irrelevance of the literary novel – certainly among men, especially younger men. As for the Booker… well, our winner in 1997 was Arundhati Roy’s The God of Small Things, which combined stylistic virtuosity and political power. Not a bad choice, as it turned out. Have a good weekend.

The picks…

Good morning, Finn here. If you cannot tell yet, this edition of the Saturday Read is a books special – with thanks to Jason for reflecting on his time judging the Booker Prize in the Nineties, and to Nick for his interview with this year’s winner. But that’s not all. Below, Tom Gatti returns to talk to us about the New Statesman’s books of the year. Outside of the strictly literary realm, Sohrab distils Trump’s vision for his second term; Francisco Garcia gets into the weeds of the true crime industrial complex; and I spend some time working out how “YMCA” became a Maga anthem.

It’s the New Statesman’s tenth year supporting the Cambridge Literary Festival, happening next weekend. You can purchase tickets here – don’t miss events hosted by our colleagues Tom, Will Dunn and Megan Kenyon. As ever, thanks for reading and have a great weekend.

1—“Giant undulations”

Few in Labour will have liked Donald Trump’s re-election; several cabinet ministers seem to loathe the president-elect. But Britain can’t afford to ignore it – thankfully, the Labour government is already restructuring its priorities in response, writes Andrew Marr. NH

Because we share a media space with America, we are vulnerable to the changed climate in Washington on – for instance – climate change, and the treatment of illegal migration. Farage-ism is boosted. One senior Starmer ally tells me: “Climate scepticism and scepticism about mass migration are going to become more mainstream simply because they are the views of the most powerful person in the world.” How will the party, including in parliament, respond? Natural Trump-haters, Labour people will loathe the spectacle of their ministers being polite, even bending the knee, to the great Orange King over the water. Starmer, as a man who thinks his first duty is to the country and state, will do whatever he believes needs to be done. It won’t make him more popular.

2—“The excesses of hyper-liberalism”

John Gray blames Barack Obama. And Nancy Pelosi. And, in fact, all of the Democratic establishment. Joe Biden’s description of Trump voters as “garbage”, like Hillary Clinton’s “deplorables”, confirms the party’s disdain for America’s working classes. The new world has no space for old Dems. GM

The collapse of the liberal order comes chiefly from overreach by American liberals. The charade in which Biden was ousted illustrates their fatal weakness. They believe their own legends. The Harris who campaigned for the presidency, less credible as a candidate than Biden, was a media simulacrum which evaporated on the night of the election. The Democrat insiders who invented the Harris facade, led by Barack Obama and Nancy Pelosi, sealed the fate of the regime they sought to renew.

3—“Overdeveloped macabre streaks”

There is a lot of money to be made when capitalising on people’s morbid fascination with death – the gorier the details the better. The true crime industry has its critics, but – as Francisco Garcia discovered at a London exhibition – it has even more shameless acolytes. His essay is as funny as it is perceptive. FMcR

That day’s weirdness came back to me as I prepared to shuffle across the exhibition space in Waterloo. What kind of tasteful offerings would the curators have in store? Certainly, it was difficult to understand what an intensely gratuitous, gore-covered reconstruction of a Jack the Ripper murder scene had to do with honouring the memory of the slain women. Or precisely what the poster offering a Top Trumps-style ranking of Britain’s Worst Serial Killers – Harold Shipman took pole position, with 1930s “Acid Bath Murderer” John Haigh coming in a disappointing tenth – did to further our collective understanding of criminology. Did the lovestruck young couple who stopped to coo at every glossy print-out and serial-killer biography really have sombre thoughts of victimhood in mind? Did the giggling adolescent German tourists who shrieked in delight at the plaster-cast model of John Wayne Gacy, clad in full clown suit?

4—“Terrestrial quandaries”

In recent years, the Booker Prize has been accused of placing politics above aesthetics, becoming something of a literary Eurovision. Fortunately this year’s winner, Samantha Harvey, whom I interviewed on Wednesday, has managed to fuse both considerations with beauty. NH

There is a good joke in the 2011 Booker Prize winner, Julian Barnes’s The Sense of an Ending, about the menagerie-poetry of Ted Hughes: “Of course, we’re all wondering what will happen when he runs out of animals.” A similar question hangs over the lyrical descriptions of the planet’s surface in Orbital: will she eventually run out of continents and landmasses, islands and archipelagos? She doesn’t: on almost every page there is an arresting line of rich description, simultaneously de- and re-familiarising the outlines of the globe. The Marshall Islands become a “fragile tracery of sinking lands so piecemeal and storm-worn”; French Polynesia is “dotted below, the islands like cell samples, the atolls opal lozenges”.

5—“A top lieutenant in Trumpland”

Over the 2010s, as a progressive social orthodoxy established itself across the culture, and particularly on university campuses, an ultra-conservative counterculture began to bubble beneath it. One of its founders and leaders was Charlie Kirk; he is now a key Trump adviser. Freddie Hayward tracks his rise and rise. NH

In the days following the election, Kirk was spotted around Trump’s Mar-o-Lago villa, reportedly advising the president-elect on who should get a job in the new administration. Kirk represents the culmination of alternative media, a consummate practitioner of transforming online influence into political power. In defeat, fewer Democrats are sneering at the online right than before; some even think the left should fashion their own. They might be too late. As Barack Obama’s former adviser Van Jones said on CNN after the election: “We were making fun of Donald Trump for having thrown away his ground game and doing some weird stuff online. We thought that [Musk and Kirk] were idiots. It turned out we were the idiots. We woke up in a body bag.”

To enjoy our latest analysis of politics, news and events, in addition to world-class literary and cultural reviews, click here to subscribe to the New Statesman. You'll enjoy all of the New Statesman's online content, ad-free podcasts and invitations to NS events.

It’s the most wonderful time of the year – when we turn over the entire books section of the magazine to a host of critics, authors and contributors, who share their favourite reading of the past 12 months. From Tina Brown to Julian Barnes, John Gray to Margaret MacMillan, Bernardine Evaristo to Ali Smith, this year’s selection is a box of delights.

What comes out top? Samantha Harvey’s Orbital was published in 2023 so doesn’t make the list (last year Mark Haddon picked it for us), but her fellow Booker shortlistee Percival Everett has the most-recommended novel of the year with James, his reimagining of Mark Twain’s Huckleberry Finn. Melissa Harrison, though, writes that “some Booker omissions are so surprising you find yourself wondering if the judges were on meth”: Evie Wyld’s snubbed novel The Echoes is “staggeringly good”, she says (and William Boyd agrees).

Beyond fiction, there’s a huge selection to add to your Christmas list: Neneh Cherry’s “enthralling” autobiography A Thousand Threads, Sam Leith’s “exuberant” history of children’s literature The Haunted Wood, Kate Conger and Ryan Mac’s “absorbing” account of Elon Musk’s takeover of Twitter, Alexei Navalny’s “funny and devastating” posthumous memoir Patriot. Time to get circling, highlighting and hint-dropping.

2024 marks our biggest construction year yet. This year, we’re building more renewable energy capacity globally than ever before. A total of 9.2 GW across three continents. Enough to power nearly eight million homes with green energy – energy that benefits climate, nature and people. Each project bringing us a step closer to our vision of creating a world that runs entirely on green energy. Find out more here

.

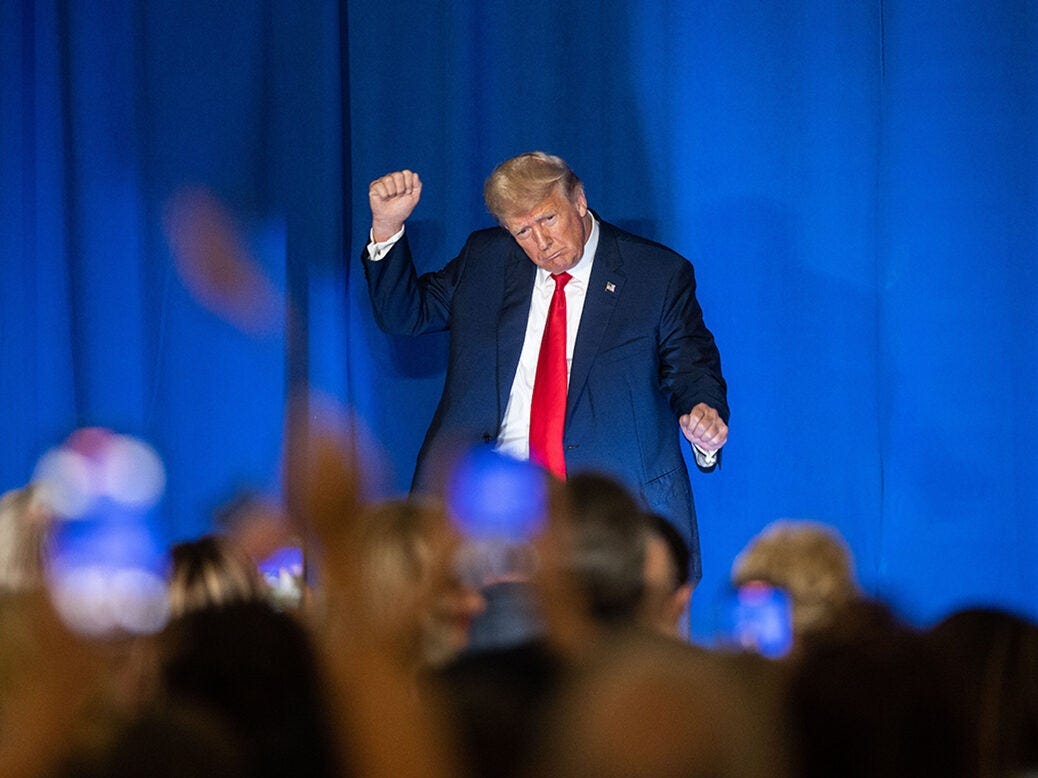

6—“Trump II, in its purest form”

Trump’s second term, Sohrab writes, will be defined by two ideas: “external protectionism and internal libertarianism”. The upside for workers is that it will protect their jobs from cheap foreign labour. The downside? An unrestrained market will exacerbate inequality. But that’s a trade-off workers were willing to make. FMcR

The corrosion of the New Deal order under the hammer blows of US elites, Republican and Democratic, has led American workers to make a drastic choice: an economy that is protected from offshoring and a reserve army of labour at the border, even as it offers fewer internal safeguards against the market power of the asset-rich.

It is hard to overstate the seismic nature, and potential dangers, of this shift. Those who believe in the dialectic might harbour a strange hope: it’s possible that the internal pressures – the labour crucible – of the 19th-century model will generate the kind of class consciousness and militancy that forced elites into striking the New Deal in the 1930s. The likes of Musk, in this reading, are the inventive but brutal robber barons whom the labour movement has to “go through” to bring about another, and doubtless very different, FDR.

7—“If Dylan is saying goodbye”

“What a f***ing t**t,” said a woman I saw outside a recent Bob Dylan concert. “Waste of bloody £200 quid!” Kate Mossman disagrees. She saw him at the Royal Albert Hall and thinks his current tour is the best in years. GM

An eccentric voice on a still-singing 83-year-old is now a wondrous voice – Dylan’s is more velvety than I recall it, or maybe that’s just the décor at the Albert Hall. Several times, I closed my eyes, or looked up into the dome, and tried to appreciate the fact that all this is coming to its end, and for now he is still here: the last person I saw on this stage was Eric Clapton, and I had a similar feeling. How amazing to be a gigantic figure like this, yet still be so protected by your own silence. At Christmas, Timothée Chalamet will play Dylan in A Complete Unknown, the biopic all about the time that he went electric. And while he may be saying goodbye, albeit slowly, he recently said hello, getting familiar with X for the first time, reviewing local restaurants, wishing unknown people “happy birthday”, and further confusing us all.

8—“The gay national anthem”

There is indeed no need to feel down, young man, especially if you are a young, Christian, Republican in America. Finn dissects the soundtrack of Trump’s romp to the White House, and notes how far the GOP has come, from its stern priggish days of yore to “the gay discotheque”. GM

Donald Trump, more than any living politician, knows how to create a moment. The photo of the now president-elect – defiantly punching the air against an azure sky and an askew American flag, blood dripping from his ear just moments after being shot in July – is a visual metaphor from Adam Curtis’s wildest fantasies. He hangs out of the window of a rubbish truck with an orange safety vest over his shirt and tie; he serves French fries in McDonald’s and looks like the subject of a Normal Rockwell painting. For all her qualities (there are some) Kamala Harris never had the aesthetic instincts of her rival.

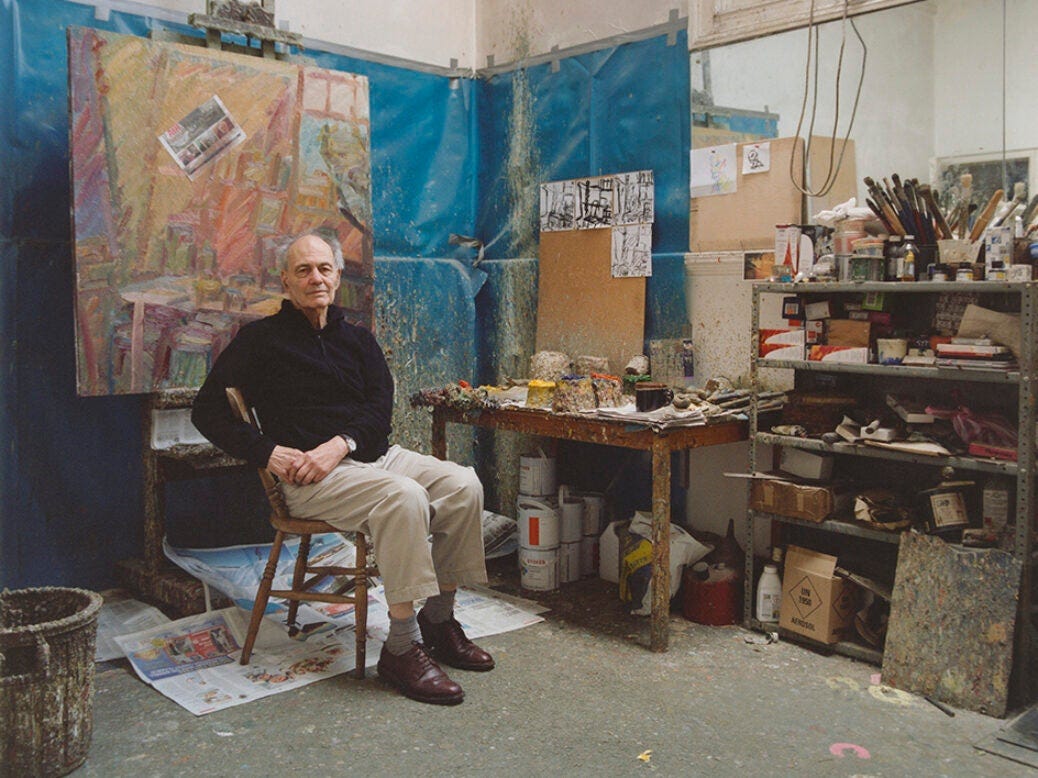

9—“Uninterested in the picturesque”

The German-British painter Frank Auerbach died this week at the age of 93. He was the last of the London School – a caste of painters who chronicled the postwar British capital and its inhabitants. Michael Prodger writes that his work is both the product of long Spartan efforts and irrational spontaneity. FMcR

Auerbach had none of the bawdiness or intemperateness of Bacon and Freud and, partly as a result, he found himself for years in their shadow. His work may have been less provocative but it was perhaps more consistently profound. The exhibition of his large charcoal portraits at the Courtauld Gallery last year confirmed him as a painter of disquieting seriousness and bottomless determination. He would never let a painting go until he felt it was right and had passed what he termed his “shit detector” test.

10—“The controversy of Zion”

In 1965, Bernard Levin wrote a celebrated essay for the New Statesman titled “Am I a Jew?”, probing his identity, and relationship to Israel and the global Jewish community. Revisiting that piece, Geoffrey Wheatcroft has produced a stunning “history of opinion”, unfolding the relationship between Israel, Jews and Britain. NH

Israel has gradually drifted away from the West in political and other ways, and that includes the Jewish diaspora, which finds itself in an agonising dilemma. David Baddiel may complain sarcastically that Jews Don’t Count, and Maureen Lipman may call the response of some of the critics of Israel “close to fascism”. But it seems unlikely that he or she feel much more affinity than the rest of us do with such ministers in the present Israeli government as Bezalel Smotrich, who once organised a “Beast Parade” as a protest against a gay pride parade in Jerusalem, or Itamar Ben-Gvir, who used to keep a portrait on his wall of Baruch Goldstein, the settler who massacred 29 worshippers in a Hebron mosque. As to the excruciating tension between the two largest Jewish communities, in Israel and the US, it was summed up by an Israeli executive quoted by Gideon Rachman in the Financial Times: “Eighty per cent of American Jews will vote for Harris. But 80 per cent of Israelis would vote for Trump.”

George’s Best of the Rest

Charlie Warzel: Bad news

Christopher Rufo: Why Boeing killed DEI

Tatum Hunter: Let’s reject location sharing

Conor Truax: Death to the internet novel

Owen Slot: Savour Gary Lineker

Cat Zhang: Is the femininomenon still happening?

Key update: Hvaldimir the whale once again believed to be Russian spy

And with that…

All quiet at the centre of the universe. In Washington DC on 5 November the air was slack and tensionless. No state voted bluer. On election night, at bars and parties it became a joke to ask: “So who are you supporting?” One woman laughed then pointed me to her Harris-Walz baseball cap, and T-shirt, and badge. She later won the bar’s raffle, but around her phone screens were flourishing the New York Times’s election ticker as the Harris odds began to plunge.

The bar emptied. The small whoop given by the badged woman as she collected her prize now sounded like a death omen. Rule and exception have swapped: Trump was not an aberration in liberalism’s long life; Biden was, instead, its death rattle. In 2016 commentators asked how to oppose the Trump paradigm – now they ask how to integrate within it.

The National Mall of the morning after was contemplative. We sat with others, quietly on the steps of the Lincoln Memorial. That is, until a pasty contingent of monument-dwellers suddenly rose and produced their cameras: Ed Balls was climbing the steps! He glad-handed and selfied. When it was my turn, he asked if I’d seen the Gettysburg Address on the wall.

“Yes, only 277 words!” I enthusiastically and incorrectly said of the famously 271-word speech.

“That’s right!” he generously answered.

— George

The New Statesman is home to the finest writing on politics, culture and ideas. To stay up to date, subscribe using the link above.

Re Zionism and the Jewish diaspora.

The views of Baddiel, Lipman and Howard Jacobsen are scarcely worth listening to. Their position tends to be Israel right or wrong and any criticism wherever it comes from is written off as anti-Semitism.

There are Diaspora journalists like Jonathan Freedland in the Guardian who take a more balanced and nuanced view.