The Saturday Read: Alternative futures

Inside: Zelensky and Putin, John Gray on Peterson, Andrew Marr on Prescott, Ireland, Lammy, and the farmers' populist revolt.

Good morning. Welcome to the Saturday Read, the New Statesman’s guide to politics, culture, books, and ideas. This is Finn, together with Nicholas, Pippa and George. We would like to thank all of our new subscribers for joining us in recent weeks.

It’s the end of an era at the the New Statesman: our editor-in-chief Jason Cowley has announced he is standing down after 16 years in post. Jason – one of the longest-serving editors of the title, alongside Kingsley Martin – began the job in 2008 when the world was a very different place. In the years since he has interviewed Tony Blair on his return to public life in 2016; guided the New Statesman through the ructions of Brexit, a pandemic, and the return of a Labour government; and profiled Rachel Reeves as he worked out Labour’s plan for power in 2023. The late Bryan Magee – the politician, broadcaster and philosopher – gave Jason his final interview in 2018.

But more than that, Jason has been a great colleague – supporting young writers early in their careers and making sure all staff are up to date on the minutiae of Arsenal football club. He will continue to write for the title, and we hope – occasionally – drop by the Saturday Read.

Before then, Jason will lead us off for one final time in our last edition of the year, bringing readers his ten favourite pieces published over his 16-year tenure. In the meantime, read on below for the best of the New Statesman this week.

The picks…

We have been all over in recent days. George Eaton went to the United Nations in New York for an exclusive interview with Foreign Secretary David Lammy; Will spent a rainy morning on Whitehall with some rather disgruntled farmers (is this the making of a serious populist revolt against the government?); and I headed to equally rainy Dublin ahead of the election on 29 November to see what is underneath Ireland’s superficially centrist politics. Freddie signs us off with a note from DC.

1—“The Kremlin’s unbridled fury”

The US has given Zelensky the green light to strike Russia with American-provided ATACMS missiles. Naturally this has provoked a significant escalation in mood and rhetoric; Ian Garner explains why Putin’s “unpredictable” threats are not meaningless. GM

Donald Trump Jr. claimed that the “Military Industrial Complex seems to want to make sure they get World War 3 going before my father has a chance to create peace and save lives”. The worry is understandable. Not since American, British, and French arms and armies were deployed against the Bolshevik government in the Civil War a century ago, and 30 years before Moscow went nuclear, have Western nations come so close to physical contact on Russian territory. Putin is an unpredictable and megalomaniacal figure who should be taken seriously. When he and his allies declare their intentions to escalate, Western leaders and publics should have cause for concern. Yet in reality, the latest bout of splenetic rage emanating from the propaganda apparatus is not aimed at us — it is aimed at the domestic Russian audience.

2—“Remote, aloof, superior”

The “liberal elite”, whom Trump made his number one enemy during the campaign, were the biggest losers of the American election. In a bravura return to the pages of the NS, Lee Siegel asks whether we can really sustain a genuine and emancipating liberalism without them. NH

To be called an “elite”, on either side, is an abhorrence in a modern democracy. There will still, however, be people who, thanks to a slew of factors, in a countless variety of contexts, and playing one of an infinite number of roles, find themselves situated above other people… What liberals must do now, instead of playing the parlour game of distancing themselves from elitism, is make a choice. Do they want to pander to the new apples of their eye, the working class? Perhaps Lasch’s sudden realisation, in The Revolt of the Elites, that “common sense” is not the magical solution to a democracy’s conflicts, is something the newly anti-elite liberal elites need to take to heart. It became “common sense” for the white working class in Germany and Italy in the 1930s to imprison and murder their liberal intellectuals. One person’s common sense is another person’s irrational fury. And Trump’s “populism” appeals to fury far more than it does to concern over wages and prices.

3—“The malady of the West”

What a delight it is to have Saturday Read favourite, John Gray, on one of the most conflicting modern philosophers, Jordan Peterson. John reviews We Who Wrestle With God and contends that Peterson has not found a higher power, but instead sounds like the run-of-the-mill liberal rationalists he claims to abhor. FMcR

One problem is that a link between Christianity and liberalism exists only in branches of the religion. Eastern Orthodoxy has never promoted freedom of conscience in the manner of post-Reformation Christendom. Even in Western Christianity the connection is not universal. Toleration emerged in countries that rejected the authority of the Catholic Church over the inner life. Tellingly, it is in these countries – particularly in the Anglosphere – that woke movements have become most powerful. Woke – or, as it is more accurately described, hyper-liberalism – is a radical secular avatar of Christianity, in which the Protestant affirmation of personal autonomy in matters of belief has morphed into the assertion that truth is subjective.

4—“Destined for conflict”

Ahead of the Irish general election on 29 November, Finn headed to Dublin – a city riven with contradictions. The politics may be stable around the centrist establishment, but this masks a simmering discontent just below the surface. PB

Since the state’s inception in 1922, only Fine Gael and Fianna Fáil – which form the current governing coalition – have ever commanded enough support in the Irish parliament to produce a taoiseach, in spite of the multi-party state. Even Sinn Féin, a party born out of Ireland’s irredentist national movement, once an alternative to the status quo, is courting voters in the middle ground. Ireland’s mainstream political culture is homogeneous, centrist and conformist, while its edges remain fragmented. The general election will not stress-test that arrangement; Ireland will likely continue – as it did at this summer’s local and European elections – to stave off the populism that has crashed over much of Europe this year. But this surface-level stability lulls the nation into a false sense of security: the chasm between government and its electorate is widening.

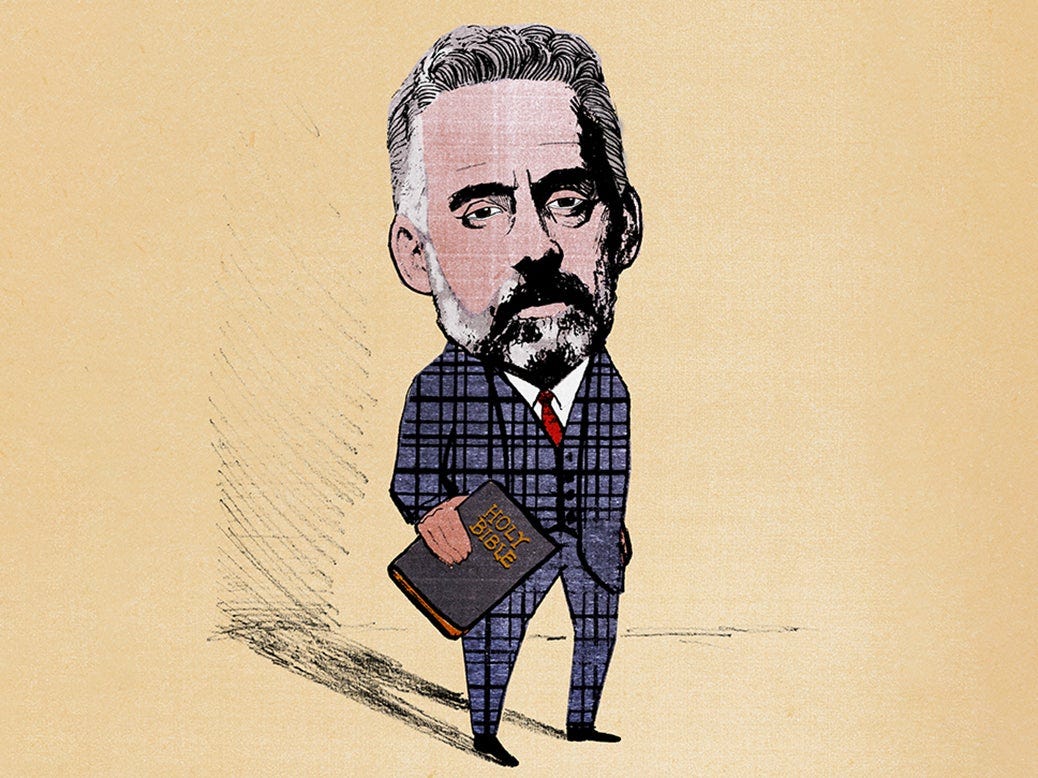

5—“Ernie Bevin of the 1990s”

Andrew Marr pays tribute to former deputy prime minister John Prescott, who died this week. Enjoy the anecdote below, and click through for reflections on how he alone could keep the Blair-Brown psychodrama stable. NH

People say John Prescott made an impact on Britain. He certainly made an impact on me: a series of vigorous jabs to the chest as, late one night in a deserted Labour conference corridor, he called me an effing bastard, saying he would “get me” in a spate of fruity language which visibly shocked the young civil servants around him. Although I was political editor of the BBC at the time and had just reported on the conference for the late-night news, I was confused. I couldn’t remember anything I’d said that could have produced such a volcanic response from the deputy prime minister. He charged off again. I stood there, silently puzzling. Then he suddenly emerged from round another corner, put a hand on my shoulder and said, “sorry about that… wrong bloke.”

To enjoy our latest analysis of politics, news and events, in addition to world-class literary and cultural reviews, click here to subscribe to the New Statesman. You'll enjoy all of the New Statesman's online content, ad-free podcasts and invitations to NS events.

Instagram Teen Accounts have new built-in protections to limit who can contact teenagers and the content they can see. Learn more.

6—“Yob rule”

From a distance, a riot can look like a rave: the flashes and flares, the pulsing mass, the possibility of injury. Crowds are historically ambiguous forces writes Sophie McBain, in this elegant review of a new study of the human herd by Dan Hancox. NH

Crowds are not always a force for good, or intent on creating a more egalitarian society. Hancox acknowledges this, and makes a distinction between the revolutionary crowd and the authoritarian one. The latter is directed from the top and works obsequiously for their master. The 6 January US Capitol rioters, he argues, were an authoritarian crowd. But not all history-making crowds seem to fall obviously into either category (how would Hancox define the Muslim Brotherhood protesters who gathered at Rabaa Square following the military-led ouster of Egypt’s Mohammed Morsi, I wondered?). Sometimes democratic values are best served by answering the demands of popular protests, and sometimes they are served when democratic institutions resist them, and it is helpful to be able to distinguish between the two.

7—“Bulldog to diehard”

The liveliest figure of our political imaginations has been dead nearly 60 years. For the 150th anniversary of Churchill’s birth this month, David Reynolds writes on the great leader’s enduring influence. He is all the things we think – defiant, resolute, bulldoggish – but he was also much, much more. GM

Today, however, facing the known unknowns of a Trump second term, at a time when the EU is struggling with a structural crisis, and Germany has lost its economic and political clout, there may be scope and space for the UK to be a significant actor. But only if it abstains from delusions of global grandstanding and accepts its role as a mid-sized power – though one with significant assets. Here’s where our national Churchill complex can get in the way. We must look to that other side of the man: the improviser rather than the bulldog. And it has to be realistic (yet adventurous) improvisation – the Churchill of 1940, not the fantasy choreographer of the 1950s. In that way, perhaps, his finest hour will not prove to be Britain’s as well. In other words, not our national obituary – all downhill after 1940 – but with the future still open.

8—“Raze the present, restore the past”

Donald Trump kept his distance from Project 2025 – a policy wish list for the restoration of ultra-Conservative America – during the election campaign. But now the Republicans have won, the project’s author, Kevin Roberts, is emerging “as the leading thinker of the incoming administration”. Freddie reviews his book. PB

To re-spiritualise America, Roberts wants to impose religion on a porn-addled, lazy, feckless nation whose education system has abandoned the Western canon. Roberts, a former president of a Catholic school, does not think America can be saved without the revival of religion; the alternative is so dangerous that Roberts flirts with theocracy. “We have in this country a glorious tradition of religious freedom, but it is not freedom from religion but freedom for religion.” America is rooted in Christianity, he writes, and so “institutions should not establish anything offensive to Christian morals”. He goes so far as to say that any institution merely “contemptuous of public prayer” should probably “be burned down”. This is a prescription hard to reconcile with a free press, the separation of church and state and the right not to partake in forced worship.

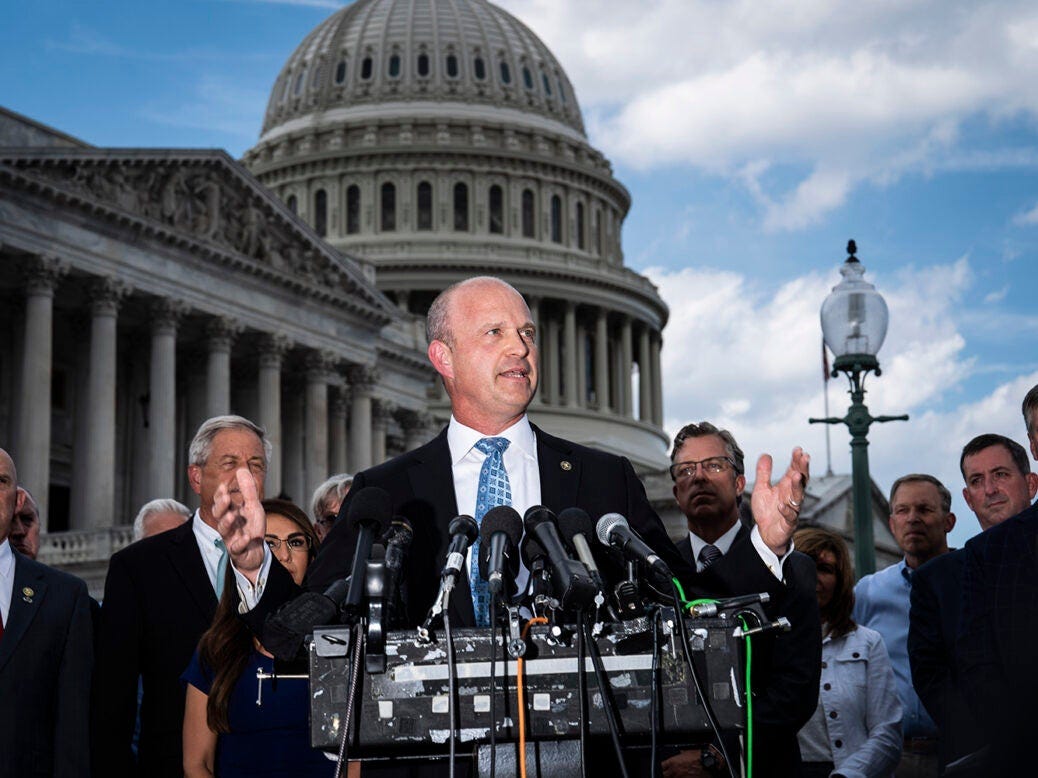

9—“A populist revolt”

Thousands of very unhappy farmers descended on Whitehall on Tuesday to protest Labour inheritance tax measures. Will joined them, witnessing the first mass demonstration of workers against this government. Through the cold and the rain Will saw Labour’s “even-handed technocracy” falling apart. FMcR

Bizza Walters, 26, hopes that she and her cousins will be the fourth generation to take on her family’s farm in Warwickshire, where her father and his two brothers raise around 500 sheep. The estate – including the land, buildings and equipment needed to make an income from it – is worth somewhere in the region of £10m. The CEO of any company with £10m in assets would expect to earn a very decent salary. Bizza’s father and his brothers, after the farm’s income has been reinvested into next year’s feed, crops, livestock, fuel and equipment, are able to pay themselves about £24,000 a year each. At seven days a week, they are effectively working for less than minimum wage.

This is the crucial difference between farmers and other business owners: most farmers wish their assets were worth less. On farmers’ forums, the prevailing sentiment is captured by an online poll which found more than 70 per cent would like land prices to fall (“like a stone” was the most popular choice). There is no landlord who feels the same way about their property portfolio, no start-up founder who wishes their share price was lower.

10—“Donald Trump doesn’t like losers”

George Eaton flew over to New York to join the Foreign Secretary, David Lammy, at the UN Security Council. They spoke about Ukraine’s future; what it’s like to have dinner with Donald Trump; and whether Labour had gone soft on China. PB

On the day we spoke, Starmer became the first UK prime minister to meet Xi Jinping, at the G20 in Rio de Janeiro, since 2018. The latter even referenced Rachel Reeves’ slogan of “fixing the foundations” of the British economy. In opposition, Labour had backed a motion declaring Beijing’s repressive treatment of the Muslim-majority Uyghurs in the Chinese autonomous region of Xinjiang to be “genocide” – a stance now abandoned. But Lammy rejects accusations of going soft. “I’ll tell you what’s going soft on China: it’s a UK where we just don’t know where we stand. I counted about seven positions on China under the last government. We had David Cameron and George Osborne’s ‘golden era’, where they were drinking beers in the pub with President Xi; we had the rather humiliating scene of Theresa May having to do a U-turn on the botched Huawei deal [for access to the UK’s 5G infrastructure]. The problem with our position on China was that we didn’t have a position. We didn’t have a position of dealing with a global superpower and that simply was not good enough.”

George’s Best of the Rest

Janan Ganesh: How Britain squandered the best hand in the world

James Meek: Nobody wants to hear this

Will Lloyd: Starmer’s farmer bashing may bloody us all

Dean Kissick: How politics destroyed contemporary art

Vincenzo Barney: Cormac McCarthy’s secret muse breaks her silence

Tyson Duffy: Reclaiming Ted Hughes

Sumana Roy: Melville doesn’t stop

Elizabeth Nelson: Thoughts on Bob Dylan and the border

Priest in trouble for letting Sabrina Carpenter film video in church. His boss: not that carpenter!

And with that…

The story of the American election can be told through the clientele of Washington DC’s bars. Groups of brash young men in dark suits are becoming an evening feature. “Republicans…” someone whispered to me when one such posse swanned into a low-lit establishment the other night. These men are ordering drinks with more bravado than before Trump’s victory. The Democrats – when they do drink – are holding their glasses a little more tightly.

The nature of the American system means swathes of civil servants are fired every four years, making way for the new administration. Old-timers can remember the optimism of the bright, young things arriving at the capital following Barack Obama’s victory in 2008. Now, even the anger which Democrats felt in 2016 has been substituted for weary resignation.

On the Sunday after the election, I went down to a climate rally a block away from the national mall. The tone was indignant and unreflective. Rally-goers were still wearing masks two years after the pandemic. Only one speaker – an impressive 18-year-old woman from the Sunrise Movement – held the Democrats responsible for their loss. But her attacks on the Democrats for not being radical on the economy rang hollow without an honest appraisal of the party’s unpopular policies on culture and immigration. As the sociologist Musa al-Gharbi tells me in our Weekend Interview, the progressive elites hold “idiosyncratic” ideas and habits which are alien to the rest of the country. One organiser hoped the election would be a “radicalising moment” for the left. That could have its benefits. But so could getting out of Washington.

— Freddie

The New Statesman is home to the finest writing on politics, culture and ideas. To stay up to date, subscribe using the link above.

Shut up and stop debating politics like it’s going to change anything—it won’t. The system is broken, and it’s designed to stay that way. No meaningful mechanism exists to hold leaders accountable. The same people in power are trusted to self-regulate—a catastrophic flaw that keeps corruption, inefficiency, and ethical breaches alive.

The destruction of small businesses, skyrocketing living costs, corporate profits driving inflation, soaring state debt, defunded health and education, and foreign-controlled banks draining billions from our economy—these aren’t accidents. Add human rights abuses, media manipulation, unlawful wars, and policies sold to corrupt donors, and it’s obvious: this is a system without accountability. Leaders act with impunity, and things will only get worse unless we demand real change.

Enter the Leadership Accountability Court (LAC): an independent, citizen-driven body that empowers everyday people to hold leaders directly accountable. The LAC gives power back to the public, ensuring decisions serve society—not self-interest.

Stop blaming politicians or parties. Stop pretending debate will fix this. Without the LAC, nothing changes. It’s not just a good idea—it’s the only solution. Face it: without accountability, you’re endorsing failure. Everything else is noise.

Jordan Peterson a philosopher? That's a laugh. Or perhaps that precisely what's wrong with him.