The Saturday Read: Angular, anarchic, awkward

Inside: Tory rot, Labour in the world, antipodal writers, and three interviews.

Good morning, and welcome to the Saturday Read, the New Statesman’s weekly guide to the best writing on ideas, politics, books and culture. This is Harry, along with Will and Pippa. Will’s written today’s lead on this week’s Tory festival of self-immolation conference. Scroll down for Pippa’s sign off from the London Film Festival.

I have been zipping around interviewing people this week. The conversations veered from Shakespeare to nuclear fusion in 24 hours. They will be with you soon. In the meantime we have a trio of interviews and a panoply of other intriguing pieces today.

If this email cuts off, you can click through to read it in full online. If today’s pieces intrigue, perhaps you might like to try a trial subscription to the NS. Read three free articles after registering on our site. A digital sub is only 95p a week. Let’s get to it.

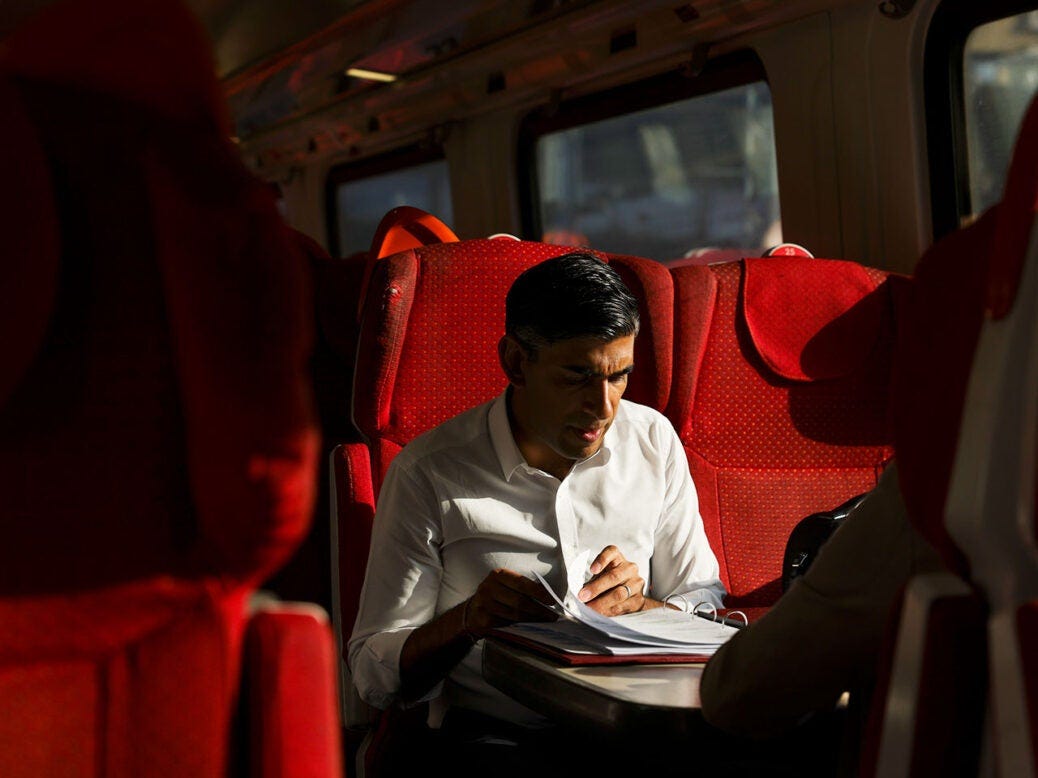

1—“The future did not belong to Rishi Sunak. It belonged to forces and personalities that are his antithesis.”

To Manchester, and the Conservative Party conference. All the headlines were made by dear Rishi Sunak, who is still technically the Prime Minister. Not that Conservatives at this annual jamboree seemed to care. They were too busy either disintegrating, as David Gauke put it, or turning into Trumpists, as Lewis Goodall suggested. Will was there for all four days so you didn’t have to be. He reports. HL

Why did Tom Tugendhat MP look so unhappy? It was 1 October, the Sunday evening at conference. The panel, where the Security Minister was joined by Michael Gove, the Levelling-Up Secretary, and Nick Timothy, Telegraph columnist and the prospective parliamentary candidate for West Suffolk, was there to discuss “the future of conservatism”. Nobody mentioned Sunak when they wrestled with the topic, which brooded over the conference for four full days.

Tugendhat, a liberal One Nation Tory who stood unsuccessfully for the leadership in 2022, is regarded as a decent, urbane man. He might have been a cabinet minister at any time in the past century for any party. Yet, as the Manchester rain fell gently outside, Tugendhat grimaced. He mentioned an extraordinary recent poll that suggested a mere 1 per cent of 18- to 24-year-olds would vote Conservative at the next election. He looked knackered: Dracula pallor, mouth stuck in a permanent upside down U-shape. But you would be unhappy if you were Tom Tugendhat, and you had to think about the future of conservatism.

2—“Now technocratic government’s smartest operator is signalling that it has had its day.”

John Gray sees something in Sunak that others do not: “After Boris Johnson’s buffoonish interregnum and Liz Truss’s kamikaze dive, Sunak has become the first serious exemplar of a new era,” he writes. Let him explain here. HL

Sunak has been accused of pandering to populism, but those who level the charge should ask themselves what it means. Populism is, among other things, the repoliticisation of causes judged to be so sacrosanct that they must be insulated from public debate and democratic choice. Conventional green agendas belong in that category, and so does immigration.

From Blair to Cameron, the de-politicisation of key areas of policy was secured under the aegis of technocratic pragmatism. Ideology no longer mattered, we were assured, only competence in delivering what the middle ground in society wanted. The actual outcome was the dominance of a single ideology – post-Cold War capitalist realism. The centre was a triangulation of positions within that neoliberal consensus.

3—“The world is a far darker and more dangerous place now than in 2016.”

Jonathan Powell was Tony Blair’s chief of staff for more than a decade. He looks at the global challenges facing Keir Starmer’s Labour Party, after 13 years of Conservative rule have put some wide dents in Britain’s international reputation. WL

The damage done to Britain’s standing in the world in the past six years is far worse than the legacy we inherited from Thatcher and Major. It will not be sufficient for Labour to not be the Tories. The three main pillars of our foreign policy – the US’s strongest ally, a leader in Europe and the soft power of development – have been systematically dismantled. To rebuild effectively, a new government will need a clear strategy in place to re-engage, and a plan to restructure the security and foreign policy machinery of government to deliver that strategy. Then world leaders will truly be able to say: “Britain is back.”

4—“I don’t think about the reader,” Fosse has written: “If I did that, I would end up feeling sorry for the reader.”

Jon Fosse was awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature this week “for his innovative plays and prose which give voice to the unsayable”. Earlier this year, Lola Seaton reviewed his seven-volume novel Septology. WL

The burden of describing Septology has weighed heavily on its critics. Several were so spiritually moved by the novel that they were unable or reluctant to articulate the experience, except by invoking stunned analogies. “The act of meditation,” Ruth Margalit wrote in the New York Review of Books, is “the closest I can come to describing” reading Fosse. Wyatt Mason in Harper’s could “only gesture at” what was striking about the book, but “felt… the urge, inexplicably, to pray”. “To describe what Septology is about,” is for Merve Emre, writing in Bookforum, “already to defile it. Perhaps it would be simpler to say that reading it is the closest I have come to feeling the presence of God here on Earth.”

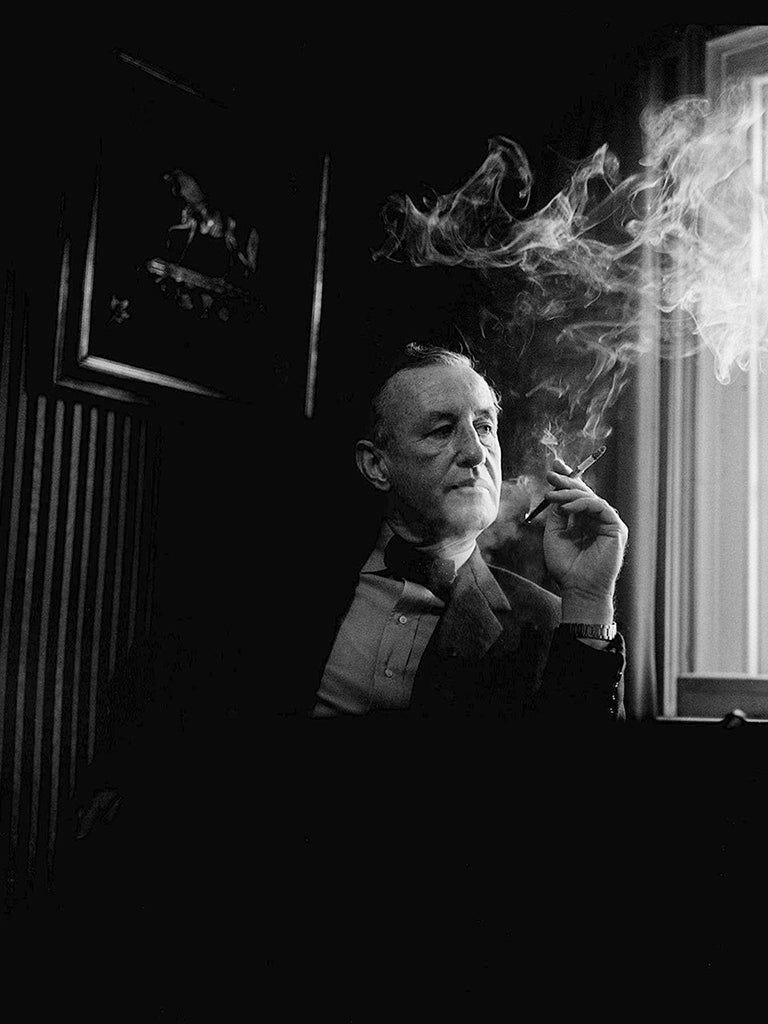

5—“I’m going to break you, Fleming.”

Who was Ian Fleming, the man behind Bond? Lyndall Gordon reviews a new biography that reveals the author of one of Britain’s chief cultural exports to be a product, like so many, of Eton’s “silken barbarity”. HL

Fleming was not decorated and his “brilliant” wartime efforts went unrecognised. Shakespeare makes a compelling suggestion that Bond’s exploits provided a fictional outlet: a way of releasing to the public schemes Fleming conceived, some of which were overruled and some carried out.

At first, between 1953 and 1956, the novels sold in respectable but not huge numbers. Then came a publicity boost during the Suez Crisis, when a collapsing Anthony Eden went to recuperate at Fleming’s beach-house in Jamaica. A further uplift came in 1961 when President Kennedy put From Russia, with Love at number nine in his list of ten favourite books. The following year the screen adaptation of Dr No launched one of cinema’s most successful franchises.

Sign up to our weekday political newsletter here:

6—“Labour is too cautious.”

Sharon Graham, the general secretary of Unite, Britain’s second largest union, tells Anoosh Chakelian what Keir Starmer gets wrong about picket lines and why she’d treat a Labour government just like any other. PB

The political moment calls for Labour leadership in the style of the 1945 government, which founded the NHS and welfare state, rather than 1997, Graham said. “I want Labour to get in, but I want it to count. There’s a difference between being in power and using your power for good. I want the Labour government to be bolder. The offer cannot be ‘a little bit better than where we are now’ – that just isn’t big enough for people. You’ve got to get them out to vote. Apathy will be the winner here if we’re not very careful.”

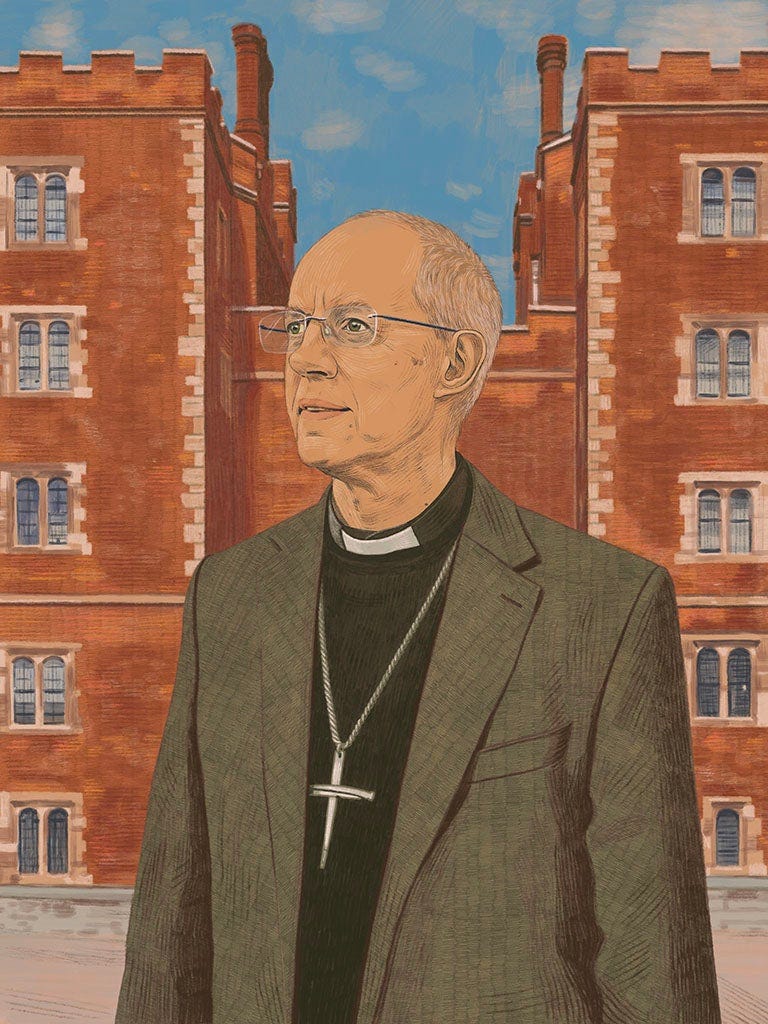

7—“It’s better to be woke than asleep.”

As the Archbishop of Canterbury, Justin Welby has one of the most impossible jobs in the country: those on the right decry his political interventions, while those on the left consider him too cautious and conservative. He talks to Kate Mossman about the refugee crisis, the fracturing Anglican Communion and how he judges when to keep his thoughts to himself. PB

Originally welcomed as a conservative but a good communicator, he was expected to be a unifying force – just as Pope Francis was. Some critics of Welby think he is too “woke”, intervening on issues he shouldn’t; others think he is not woke enough. He has spoken out against Brexit, Universal Credit and Suella Braverman’s immigration policies: he described her plan to send refugees to Rwanda as “ungodly” in an Easter sermon. Last month, his team confirmed that Braverman had refused a request to meet. Welby has defended trans rights, but for years sat on the fence about same-sex marriage, trying to hold together the fragile coalition of the Anglican Communion.

Writing in the Daily Mail last year, the columnist Stephen Glover accused him of spouting “trendy, shallow nonsense… one of the most garrulous and outspoken primates to have occupied Lambeth Palace since the Reformation”. Yet gay rights campaigners have demonstrated outside the palace, too.

8—“Anne Boleyn was not simply a stray femme fatale.”

Rowan Williams (it’s a big week for archbishops of Canterbury) asks whether we really need another book about Henry VIII and Anne Boleyn. Then he reads Hunting the Falcon by John Guy and Julia Fox, and finds it a “genuinely useful addition to the abundant literature about a period when the rule of law was more violently abused than at any other period in English history”. PB

Part of the story that Guy and Fox tell is about how Anne rapidly became a diplomatic liability rather than an asset. The humiliating spectacle of the divorce proceedings in the early 1530s, culminating in the hasty cobbling-together of an independent English ecclesiastical court to do what the King wanted (with the consequent rejection of the Pope’s jurisdiction), did not inspire confidence abroad.

In late 1535 a French diplomatic mission to England made it clear that Anne was an embarrassment and that any hopes of an Anglo-French entente cordiale, based on resistance to the Pope and recognition of Henry’s marriage to Anne (and of Elizabeth, the daughter Anne had borne to Henry), were pure fantasy.

9—“Germany remains divided between an east that looks towards the East and a west that looks towards the West.”

Wolfgang Münchau explains that Germany’s recent fall from economic success was no such thing. A sceptical observer could have foreseen that trade imbalances, dependence on Russian gas and the nation’s own supplies of coal, would eventually reveal major problems. Extremism is on the rise there for a reason. WL

My expectation is that Germany will remain anchored in the Western alliance, but German society has no appetite for increasing military spending, or for creating an alternative EU-wide security system. It will remain dependent on the US for security. The US has also become Germany’s largest export market. Unless the US were unilaterally to revoke its commitment to European security, for example if Donald Trump were to become president again, Germany will stay a loyal ally. But there is a cost to be paid. East Germany will not be on board. Old divisions will resurface.

10—“Socialists periodically predict the downfall of capitalism, but each decade the coffin remains empty.”

George has interviewed Yanis Varoufakis, the former Greek finance minister whose views now spiral in all sorts of directions (a Trump presidency would be good for the world; Starmer offers nothing; Biden is betraying Ukraine). HL

Varoufakis traces the right’s resurgence back to Syriza’s decision to ignore the 2015 bailout referendum result, in which the Greek people refused to accept EU austerity – the act that prompted his resignation as finance minister. “After eight years of this, the vast majority of people don’t care as to who was right and who was wrong… they look at both of us [him and Alexis Tsipras, the prime minister at the time] and say, ‘Bugger off. You gave us hope and then you dashed that hope.’”

Syriza, which originated as a radical left party, is now led by Stefanos Kasselakis, a shipping executive and former Goldman Sachs trader. “It’s worse than New Labour, it’s closer to the Democrats… I know nothing about him, I’d never heard of him till August; nobody had heard of him. He comes along with one video on YouTube and he wins. That’s when politics becomes depoliticised as a result of the failure of the left to keep it political.”

Will’s Best of the Rest

New Yorker: Jon Fosse’s search for peace. I want to read about his search for producing a novel that is shorter than his usual seven volumes.

Telegraph: Badenoch odds-on to be next Tory leader. People said this about Micahel Portillo. He now makes documentaries about trains.

Bloomberg: The secret plot against the WHO head.

Elizabeth Lopatto: How the Elon Musk biography exposes Walter Isaacson.

Jennifer Szalai: Michael Lewis can’t make a hero out of Sam Bankman-Fried.

Amanda Craig: How a silly blond toff transformed crime fiction. Other species-level events pioneered by dumb blonds include the conquest of Gaul.

Patrick Maguire: The real power behind Starmer.

Madeline Grant: The Tory party is becoming a drunken tramp. You know it’s bad when the Telegraph’s best writer is saying this.

Our hang-up with cougars. One of those pieces that might be about something going on in the writer’s life, but who could say?

Elsewhere on the NS

“Ah, briny, blustery Liverpool! For a conference all about order, predictability, stability and a smooth, unemphatic road to power, it’s hard to think of an odder venue for Labour than this great port city of radicals and immigrants, which in some ways seems barely English: it keeps its angular back to the rest of the country, and its default political culture is anarchic, jostling and awkward.” Andrew Marr previews this week’s Labour conference.

David Muir, a former close aide to Gordon Brown as prime minister, imagines a future in which China has invaded Taiwan – and Keir Starmer, as PM, must decide how to fight alongside America.

The Labour peer and former diplomat Catherine Ashton recalls dining with Putin in this week’s Diary.

How did Sharon White, a lauded civil servant, lead John Lewis astray? Will Dunn reports. (“That was one of the big moments,” a former partner told me, “where our customers turned around and said, you didn’t know what you’re doing.”)

For our Weekend Essay, Phil Tinline gives some much needed context to the rise of Starmer’s Labour.

Blind hatred never built a house. Be nice to Nimbys, writes Finn McRedmond.

The short-story writer Lydia Davis tells Ellen Peirson-Hagger why she’s declaring war on Amazon.

Sophie McBain on the deluded world-view of “confused boy” Sam Bankman-Fried.

How to get into: Inventive novels

This week Tom Gatti, our executive editor for books, print, ideas and culture, offers three books that capture fiction at its most novel.

The Private Memoirs and Confessions of a Justified Sinner by James Hogg (1824): The Goldsmiths Prize – for work that “extends the possibilities of the novel form” – has just announced its 2023 shortlist. Had the prize been around in 1824, this book would have been a shoo-in. It follows a young man, Robert, whose Calvinism, aided by a shady companion, urges him to commit atrocities. The story is told by an editor, and then by Robert himself: an unholy metafictional mash-up and an unsettling evocation of paranoia and psychosis, Hogg’s novel is thrillingly unorthodox.

Ducks, Newburyport by Lucy Ellmann (2019): This did actually win the Goldsmiths Prize. Telling readers that it is a 1,000-page interior monologue, largely in a single sentence, tends to put some off, so instead I’ll focus on its fizzing wit, propulsive rhythm and political urgency. An unforgettable book.

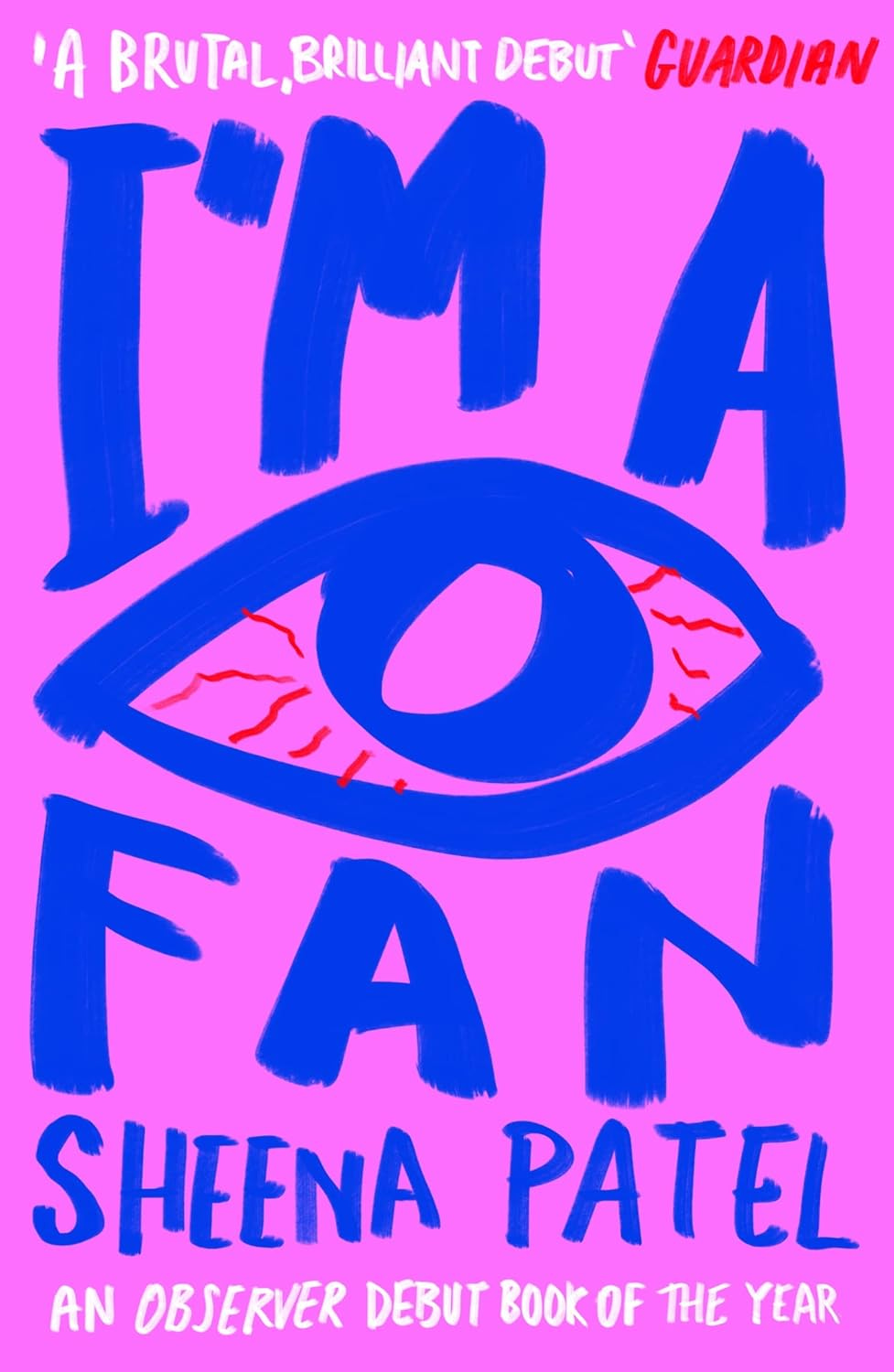

I’m a Fan by Sheena Patel (2022): As short and intense as Ducks is capacious, I’m a Fan has a young woman describing her relationships with “the man I want to be with” and “the woman I am obsessed with”. Through vignettes that are shuffled and dealt like a pack of cards, Patel assembles a portrait of a mind that is deeply perceptive about privilege, laugh-out-loud funny about online identity, and in many other respects utterly unhinged.

And with that…

While the serious politicos fell over themselves to tweet the funniest thing from the Tory conference, I stayed in the capital for the London Film Festival. Proceedings opened on Wednesday with Emerald Fennell’s Saltburn, a lurid skewering of toffs with cruelly high cheekbones. It’s as gleeful and darkly comic as you’d expect from the writer-director of 2020’s provocative Promising Young Woman.

I had great hopes for David Fincher’s The Killer, in which Michael Fassbender plays a joint-cracking, Smiths-obsessed assassin. But although it’s everything we’ve come to expect from the Fight Club director – stylish, propulsive, wincingly violent – it had a straight-to-Netflix energy.

Far more emotionally and intellectually stretching was Todd Haynes’ May December, loosely based on the case of Mary Kay Letourneau, who was jailed for rape after having a sexual relationship with a 12-year-old (and having his child) – only for the two to marry once she had served her time. Julianne Moore is on fine neurotic form as Gracie, whose unconventional family life is interrupted when an actress – Elizabeth (Natalie Portman), who is due to play Gracie in a film – visits to study her subject. It’s an uncomfortable and at times funny psychological horror, with Portman and Moore circling each other like lionesses.

Still to come: All of Us Strangers, a ghostly romance starring Andrew Scott and Paul Mescal, and a film adaptation of a childhood favourite, Michael Morpurgo’s Kensuke’s Kingdom. A black-tie wedding in Chelsea next weekend may prevent me from seeing a sequel 23 years in the making – Chicken Run: Dawn of the Nugget.

Thank you for reading. Don’t miss out – subscribe to the New Statesman and stay up to date with everything you need: from news and analysis to comment and criticism.

Whether you’re looking for a sharp blog or a finely written feature, the New Statesman has you covered. Have a good week, and catch you next Saturday.

Thanks to Chris Bourn.

I'm new to Substack and still finding my feet. But just want to say that I look forward to reading this every week. This newsletter is what inspired me to finally subscribe to the New Statesman. Thank you.

On Sharon Graham’s article about Labour needing to be bolder.

It will be very interesting to see how Labour positions itself as they head into their conference this week. To date, the strategy appears to be to sit tight, say very little and hope the Tories implode. Not a bad strategy but it only gets you so far.

At some point the voters are going to want to know what Labour stands for. What does it mean for taxes, spending and public services. We live in a world where money is scarce. This isn’t 1997. There really isn’t any money left.

So it will be down to choices and trade offs. This is all boring stuff for an electorate looking for hope and inspiration.

The real danger for Labour is that the silence turns people towards the populist messages of the emerging Tory campaign. In this vacuum, extremism can proposer.