The Saturday Read: Bonfire of the vanities

Inside: Oasis, Donald Trump, Vladimir Putin, the Queen and the Kennedys.

Good morning. Welcome to the Saturday Read, the New Statesman’s guide to politics, culture, books, and ideas. This is Finn, together with, Nicholas, Pippa and George.

The last day of August is a good time to reflect on the defining events of this rather unusual summer. The first half was almost entirely dominated by the general election and the end of 14 years of Tory rule. But Labour’s honeymoon was short: in the comedown of their victory the country was beset by riots and the disturbing sight of ethno-nationalism on the streets. Donald Trump survived an assassination attempt; Joe Biden clung on as long as he could, before the powers in the Democratic establishment finally twisted the knife. Despite a shaky start, the Paris Olympics were a triumph. Charli XCX and her boorish Brat completely captured the zeitgeist. And then, the most incredible news of all: Oasis announced their reunion.

In the latter half of August things have been relatively quiet in England and we have been looking, instead, to America. Last week we asked you who you thought would win the election in November. Among the thousands of votes cast, 84 per cent think Kamala Harris is on course for the White House, compared to the slim 16 per cent who think Trump still has it in him. The real polls are very tight (Ben Walker – our data whizz – breaks down the numbers here). I wonder if this confidence is primarily thanks to the celebratory atmosphere of the Democratic National Convention – even from a distance it was clear the mood in the party had shifted from defeatist and neurotic to energetic and joyful.

The question now is whether Harris can sustain this surprising momentum. November is a long time away, and there is ample opportunity for a misstep. If nothing else, the summer has reminded us how quickly events can spin out of control and coherence.

The picks…

Good morning, Nicholas here. This week, Sohrab Ahmari writes a first-class cover story about how Trump needs to rediscover his populist roots. His piece similarly leads the Saturday Read today. Phil Whitaker looks at a question tugging at the soul of the NHS. And Robert Harris talks to Pippa about World War I. As ever, thanks again for reading and have a great weekend.

1—“The dumbest, most boring version of the post-Reagan right”

Donald Trump is having an identity crisis – spooked by Kamala Harris and reliant on the good favour of a coterie of tech billionaires. Now, the man who shook up the establishment in 2016 is starting to sound like Mitt Romney. Sohrab asks how Trump can reclaim his populist mantle. FMcR

The trouble with defining Harris reflects the Trump campaign’s own identity crisis: is Trumpism still an uprising against elites and the American status quo in the opening decades of the 21st century? Or is the movement settling into familiar conservative patterns, battling “communist” phantoms, allying with powerful segments of American capital and abandoning a post-neoliberal trend first heralded by Trump himself in 2016? Evidence is mounting in favour of the second proposition: that Trumpism 2.0 is more conservative than radical or populist.

2—“Diffuse, headless, communal euphoria”

For better or worse, the Gallagher brothers are the rock ’n’ roll dynasty to whom I owe fealty, despite only having recently turned ten when Oasis split up. Now (pending the nationwide crush for tickets taking place this morning) that I have the chance to see them for the first time, I wrote about what makes their music special. NH

I think the only explanation can be the street romanticism their music encapsulates… Oasis’s most resonant lyrics might be considered thin written down, trading in a shopworn sentimentalism that eschews detail and sometimes coherence. But, such as it is, the imagery is universal, cycling through “souls” and “storms”, visions of weather and the natural world, of rebirth and renewal: “I live my life for the stars that shine”; “I just wanna fly/Wanna live, don’t wanna die”; “Wake up the dawn and ask her why/A dreamer dreams she never dies”.

3—“Vengeful, violent citizens”

Ukraine’s incursion into Russia’s Kursk region has brought Vladimir Putin’s army of young conscripts, who are usually protected from being sent to the front lines, into combat for the first time in over 20 years. Ian Garner analyses the implications for Russian civil society, asking whether Putin is inadvertently creating his own enemy within. NH

In a country in which returning troops committing violence is becoming common, betrayed conscripts may follow not in the footsteps of the heroes they see in the state’s movies about the Second World War, but in those of the Afghanistan generation. If the state does not respond to their concerns, and if the wider public at some point in the future tries to forget Russia’s brutal war on Ukraine, these men may find themselves on the periphery of society. If so, their experiences of betrayal and disappointment may lead them to bring yet more violence to the Russian Federation – and to threaten the national stability that Vladimir Putin has long made the foundation of his rule.

4—“No one wants to be a bad mother”

In Mother State, an ambitious history of British motherhood over the past 50 years, Helen Charman argues that all mothers are in some way part of the machinery of the state. Megan Gibson found that hard to accept. PB

Mother State argues that motherhood is not merely politicised, but needs to be understood as a political state in itself. Charman writes that the campaigns of recent decades – on the politics of breastfeeding or the rising costs of childcare – are worthy but atomised, and “fall short of understanding motherhood in its entirety”. Just as feminism made us acknowledge that what had once been considered private and natural was actually public and socially constructed, motherhood is due for a similar awakening. And yet, in politics and culture, it remains stubbornly in the domestic realm “where it can be conveniently ignored”.

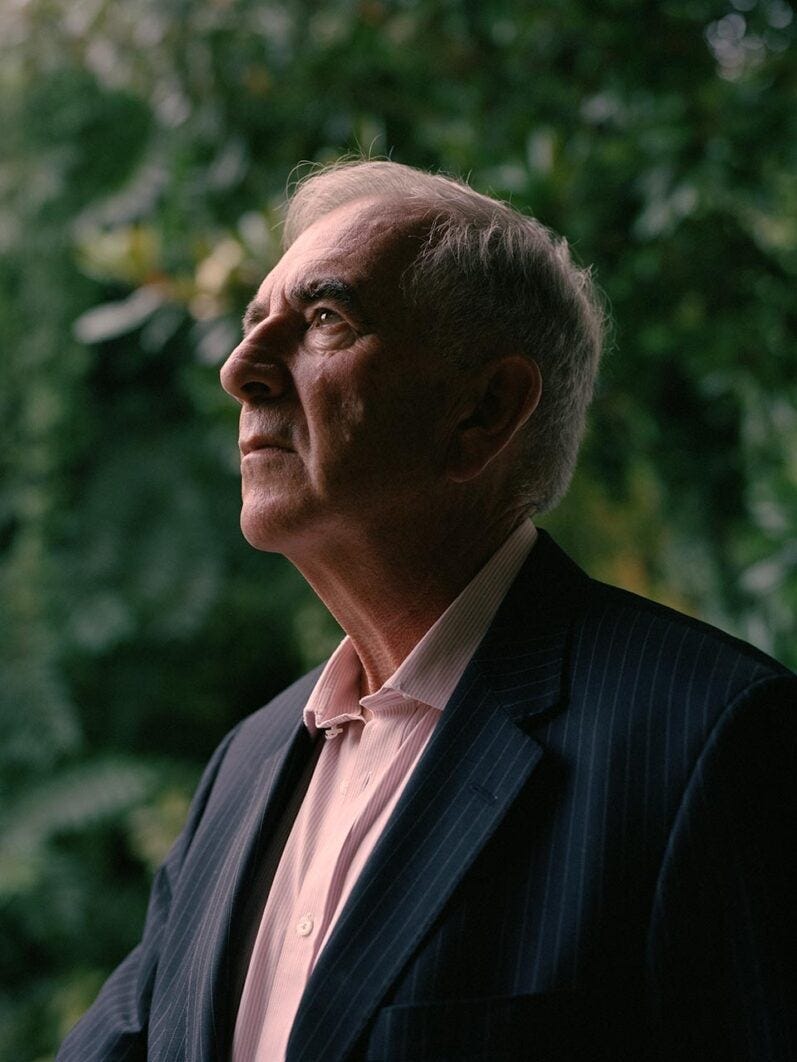

5—“The great politicians, they’re like artists”

Recently, Pippa met the historical novelist Robert Harris in anticipation of his new book, Precipice, set in 1914 (and about, you guessed it, Europe on the brink of war). There is more than one Robert Harris fan in the New Statesman office it seems. Coincidentally, this summer I reread (and highly recommend) his Cicero Trilogy. FMcR

Since Fatherland, Harris’s novels have roamed from Ancient Rome to 19th-century France at the time of the Dreyfus affair to a modern Vatican, but the First and Second World Wars keep drawing him back. The novelist was born 12 years after the end of the Second World War – “So, what’s that? The equivalent of 2012. It seemed at the time a huge gulf, but now I see it was nothing” – and believes we still “live in its shadow”.

“I think 1914 is the pivotal year in modern history. There’s a world before that and then a world after that. It was a breakdown of international order that had been preceded by upheavals intellectually, socially, after a long period of peace. It’s not hard to feel one’s living in that kind of period now.”

To enjoy our latest analysis of politics, news and events, in addition to world-class literary and cultural reviews, click here to subscribe to the New Statesman. You’ll enjoy all of the New Statesman’s online content, ad-free podcasts and invitations to NS events.

One of my favourite things about the summer months is giving myself – and readers – a break from the self-involvement of my back-pages column, Deleted Scenes (if you’ve not read it, think dating disasters, recurrent rental crises, and deep grief at my friends getting married and having kids), and handing it over to some of my talented colleagues. Earlier this month, Rachel Cunliffe wrote a moving piece about Jewish weddings, a funeral and finding hope in a time of great loss. And this week, Megan Kenyon takes us to her parents’ garden in Cumbria, which has a new inhabitant of the red squirrel variety. Alas, normal service resumes in a fortnight.

6—“America is in the throes of a far-reaching crisis”

How’s Western liberalism getting on? Badly, thinks John Gray. Neither of the US’s main political parties will accept a November loss as legitimate, he contends. Either result would likely trigger civil disorder “more protracted and more lethal” than the recent British riots. GM

The dethroning of Joe Biden will be followed by other regime shifts. Robert F Kennedy Jr’s endorsement of Trump suggests the game is not over, but a Harris presidency would be transitional in any case. As the intractably divided country threatens to slide into disorder, authoritarian demagogues more disciplined than Trump will appear on the right and the left. And as in the former Soviet Union, geopolitical retreat will surely be followed by nationalist self-assertion. Whatever the outcome of this election, America will rise from the wreckage of the post-Cold War global order as a post-liberal great power.

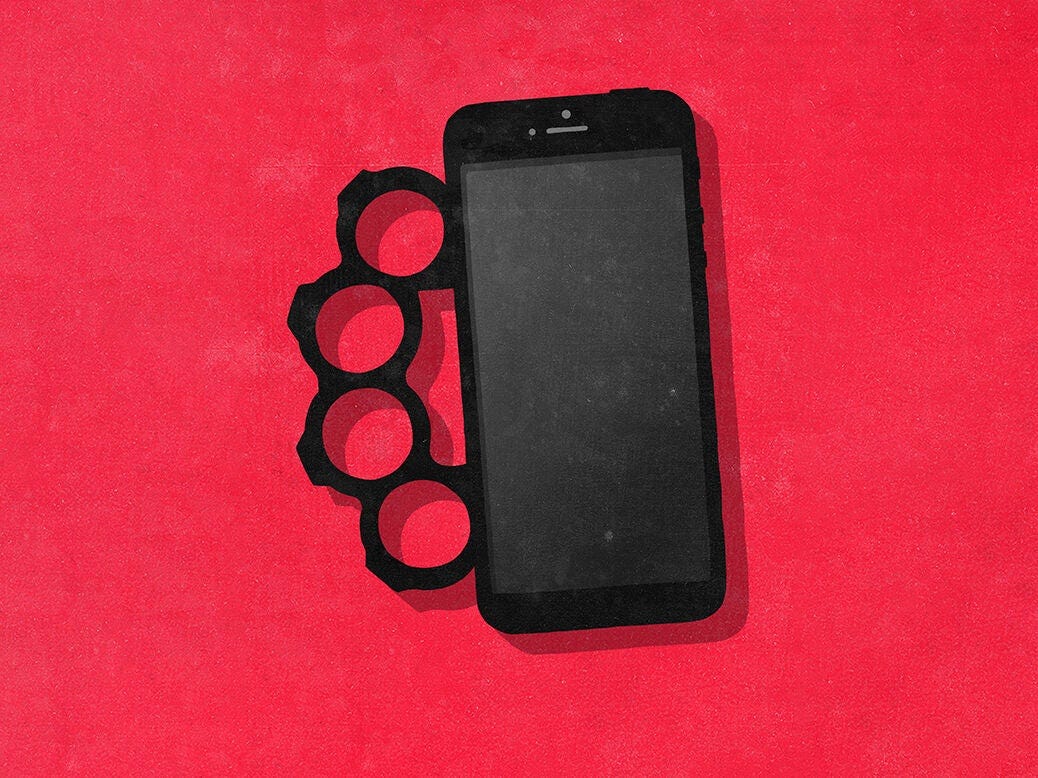

7—“The fight will be long, brothers”

What do far-right rioters, Islamist terrorists and election fraud conspiracy theorists have in common? The encrypted messaging app Telegram. Julia Ebner and Jacob Davey explain why the platform is an ideal incubator for extremism and violence. PB

The infrastructure of closed-chat applications accelerates dangerous group dynamics. Trigger points – events considered transformative or emotional, like a tragic attack or an election defeat – help foment something called “identity fusion”. Members on private channels merge their personal identities with a larger group identity. They start to view other members as kin-like, often referring to each other as “brothers” or “sisters” (evidenced perfectly by the Southport overture: “The fight will be long brothers.”)

8—“I saw a living goddess”

Half of everyone on the planet watched Queen Elizabeth II’s funeral, according to some estimates. A new book by Craig Brown explores one human’s impact on billions. The eminent historian Margaret MacMillan finds it a balanced, insightful account. GM

Occasionally the woman behind the role peeps out. In the Christmas speech of 1992, the year Princess Anne got divorced, Charles and Diana separated and much of Windsor Castle burned, the Queen talked about how, like other families, hers has had some difficulties. More recently, when the Sussexes lobbed accusations of royal racism from California, the phrase “recollections may vary” was apparently the Queen’s own. She was obliged to entertain some appalling people, from Idi Amin to the Ceaușescus but made it clear she did not like them. President Donald Trump she found “very rude” and wondered why on Earth his wife stayed married to him. There is no danger here of candyfloss overload.

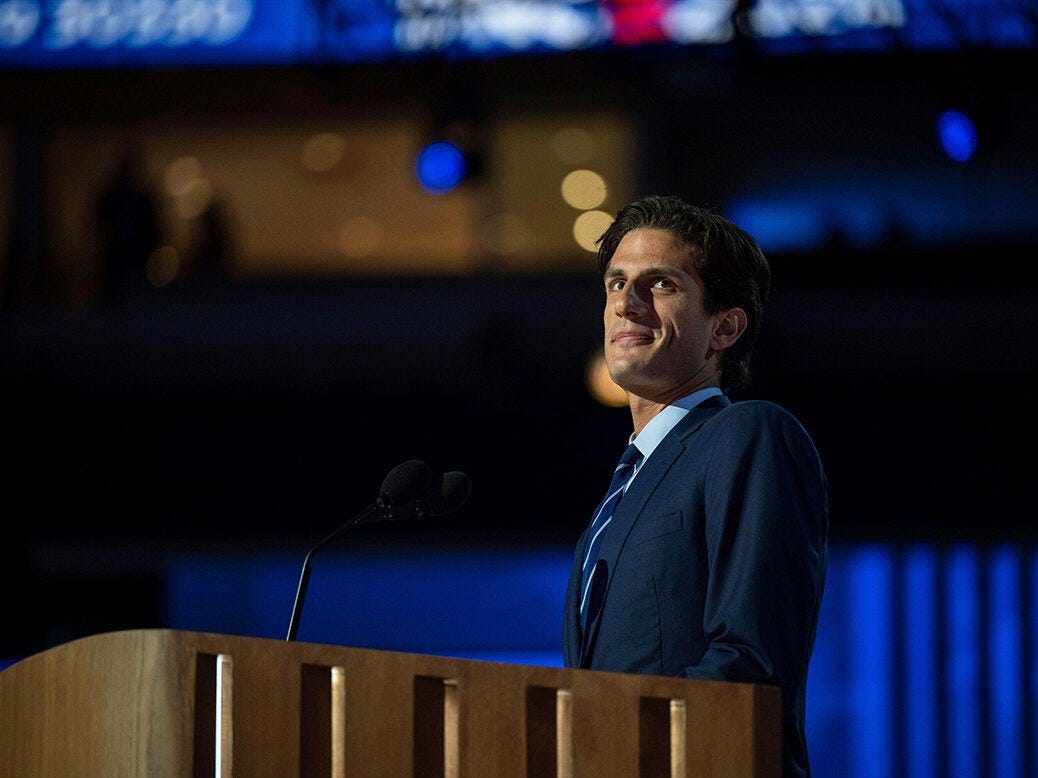

9—“America’s vanity heir”

The newest Kennedy on the block is the young, telegenic and foppish Jack Schlossberg – a social media sensation and, for some reason, Vogue’s political correspondent. Kara Kennedy (no relation!) interrogates his hollow appeal. FMcR

The last example brings us to the public face of the latest generation of Kennedys, Jack Schlossberg, son of Caroline. Recently named as Vogue magazine’s political correspondent, Schlossberg has made a name for himself as… just kidding. His name was made already. But he has used his name – which changes from Kennedy Schlossberg to Schlossberg, depending on the setting – differently to how his parents and grandparents and aunts and uncles traditionally have. Today, given the privilege of good looks, money and fated success at whatever you choose, the thing someone would choose is TikToking and being a journalist. The king of Camelot today is he who posts.

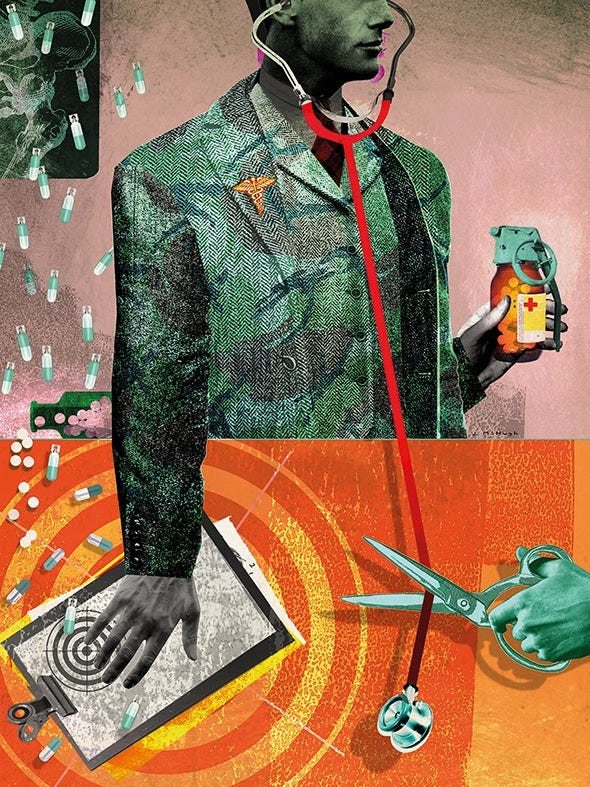

10—“Demoralising bottlenecks at every stage of medical careers”

Conflict has erupted within the NHS over an attempt at cost-cutting: the expansion of the role of medical associate professionals. With two years of condensed medical training, these practitioners are expected to alleviate the pressures on doctors by taking on “simple” cases. This new medicine war, our medical editor and practising GP Phil Whitaker writes, cuts to the heart of what a doctor is for. PB

The core problem – whether in general practice, hospital medicine or the administration of anaesthesia – lies in the concept of the “simple” case. Which cases are simple can only be determined after the fact. Most chest pain is trivial, but some instances herald major heart or lung pathology. Most headaches are migraine or tension, but some can reflect serious disease of the brain. Leg pain and breathlessness might indeed be due to muscular injury and anxiety, but some will be due to pulmonary embolism.

George’s Best of the Rest

Carrie Battan: Sabrina Carpenter, blonde girl.

Blanca Schofield: They’ll be there for you: 30 years of Friends.

Joshua Barone: All hail Pevear and Volokhonsky.

Morten Høi Jensen: When Hitchens was good.

Billionaire’s lazy-river plan outrages Harry and Meghan’s community. Cool off, folks.

The best pictures from the Wildlife Photographer of the Year 2024.

And with that…

On Wednesday night, I went to see Geoff Dyer in conversation in central London. Geoff is one of literature’s exemplary bohemians, best known for his writing on such exotic subjects as Tahiti, drugs, Burning Man and Tarkovsky. A decade-long residency in California has only deepened this sunny charm. But key to his comedy has always been a certain salt-and-vinegar Englishness. And, though he’s written nearly as much about them as he has on Nietzsche or Adorno, I’ve always felt that the influence of more flinty writers like Raymond Williams and Philip Larkin has been understated.

Now he is returning to Britain permanently. His next book, Homework, is a family memoir about growing up in Cheltenham in the 1960s and 1970s, taking in the shadow of the Second World War, his working-class origins and his grammar-school adolescence. This world – the land of Airfix, currency devaluations and the 11-plus – feels very “in the air” at the moment. After all, our new-ish Prime Minister is a contemporary of this Dyer generation, and a product of the similar aspirational-educational trajectory. And Starmer is most often compared to Harold Wilson, the presiding political force of that time.

Speaking at the event, Geoff said the memoir was in part a social history of this “vanished England” and of his “being the beneficiary of a particular historical moment” of social mobility. I’ve often thought that moment in England’s postwar history has long deserved the kind of granular treatment Annie Ernaux gave France in her masterpiece The Years. Perhaps Dyer’s book can supply the positive vision of an England of “change” and an optimism our politicians seem unable to summon up.

— Nicholas

The New Statesman is home to the finest writing on politics, culture and ideas. To stay up to date, subscribe using the link above.

"The trouble with defining Harris reflects the Trump campaign’s own identity crisis: is Trumpism still an uprising against elites and the American status quo in the opening decades of the 21st century? Or is the movement settling into familiar conservative patterns, battling “communist” phantoms, allying with powerful segments of American capital and abandoning a post-neoliberal trend first heralded by Trump himself in 2016? Evidence is mounting in favour of the second proposition: that Trumpism 2.0 is more conservative than radical or populist."

This passage is the journalistic equivalent of describing imaginary figures in clouds.

Back on Earth, Trump used the presidency to advance his interests and those of his immediate family members and as an outlet for his basest impulses, most notably xenophobia and racism. How could it be otherwise? Trump showed no interest in the office apart from the trappings and the ability to threaten opponents with punishment. If anyone thought Trump was going to shake up the nation's elite, it was the press looking for a coherent narrative where there was none or the rubes, who we now know Trump referred to as "basement dwellers."

That "Trumpism" was an assault against elites and the American status quo would come as a surprise to the ultra-rich who were the beneficiaries of Trump's only real legislative accomplishment, a massive tax cut that screwed the middle class and created the largest deficit in American history.

It is ludicrous to treat Trumpism as a political movement in the conventional sense. Trumpist politicians live in fear of having their careers ended by a wrathful Trump or his feral base, and they carefully tailor their words and deeds accordingly. At the federal and state level, Trumpists live to pursue Trump's personal vendettas, interfere with attempts to bring Trump to justice and lay the groundwork for another attempt to steal a presidential election. Their legislative agenda, such as it is, amounts to further assaults on reproductive freedom and the on separation of church and state in order to codify right-wing Christian beliefs.

As Never-Trump conservative exiles from the Republican Party have made clear time and again since 2015, there is absolutely nothing conservative about Trumpism. Here is how The Financial Times put it in 2023:

"It seems a fair bet that the philosophical revivalists of American conservatism in the 1950s and ’60s — political theorist and social critic Russell Kirk and William F Buckley Jr, the National Review editor whose watchwords were fiscal responsibility, limited government and a forward position in the world assuming American leadership — would not have recognised much in the Trump presidency embodying those principles." https://www.ft.com/content/3b9a4ec5-8b5c-4f62-9da9-121d12743c7b

There's no need to speculate as to the nature of a second Trump presidency. Trump always says ahead of time what he intends to do. Compulsive liar that he is, Trump has denied knowing anything about the radical Project 2025. Trump also denied knowing E. Jeanne Carroll, and look how that turned out. Trump has his fingerprints all over Project 2025, as do Trump henchmen such as the ghoulish Stephen Miller. The Washington Post calls Project 2025 "a blueprint for the second Trump administration. These are some of the highlights:

"The centerpiece is a 900-page plan that calls for extreme policies on nearly every aspect of Americans’ lives, from mass deportations, to politicizing the federal government in a way that would give Trump control over the Justice Department, to cutting entire federal agencies, to infusing Christian nationalism into every facet of government policy by calling for a ban on pornography and promoting policies that encourage 'marriage, work, motherhood, fatherhood, and nuclear families.' " https://www.washingtonpost.com/politics/2024/07/12/project-2025-summary-trump/

How is that agenda even remotely conservative? There's a reason that knowledgeable observers regularly refer to Trump's authoritarian tendencies.

Finally, Trump's weird penchant for calling Kamala Harris and other Democrats "communists" has nothing to do with American conservatism's Cold War phobias. Instead, it is straight out of Trump's playbook of repeatedly telling outrageous lies about his opponents. By now Trump has so thoroughly shattered his base's grip on reality that they will believe anything he tells them. Never mind that the Rosicrucians probably rival today's American communists in number and influence. Trump might as well be calling Harris a witch.

Cognitive dissonance: "Sohrab asks how Trump can reclaim his populist mantle." Despite some otherwise insightful observations, the writer either takes DT seriously or adheres to the tradition of horse-race journalism. Regardless, never buy a currency that is not backed up by a navy -> do NOT buy Trump's new crypto-currency.