The Saturday Read: Bright green light

Inside: Starmerism, Swinney, the Saudi golf grab, campus strife, Dublin, and Brentford.

Good morning. Welcome to the Saturday Read, the New Statesman’s weekly guide to politics, culture, books, and ideas. This is Harry, along with Jason, Pippa and George.

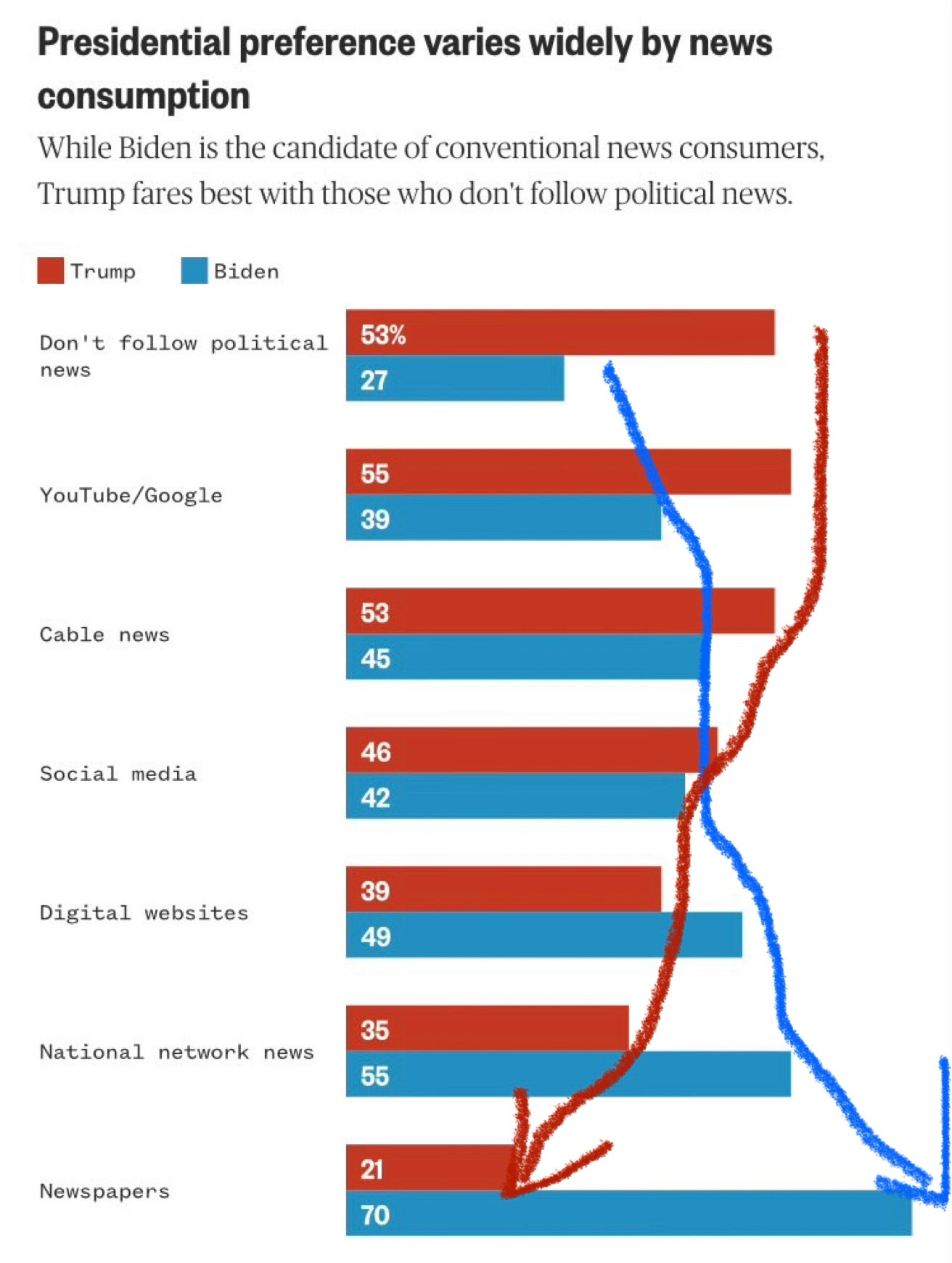

Before this week’s picks, here is a fascinating (sobering?) graphic for you, which I have annotated in crayon. It shows support for Trump and Biden split by how a voter gets their news. Trump’s superficial appeal is sustaining him, whatever it is exactly.

He is thriving in news deserts, among people who don’t follow the news at all, or only follow events on YouTube and Google. Alphabet owns both companies. If Trump wins this year, expect a wave of think pieces attacking it for the way it has allowed these platforms to develop as sources of information, just as Facebook was attacked in 2016.

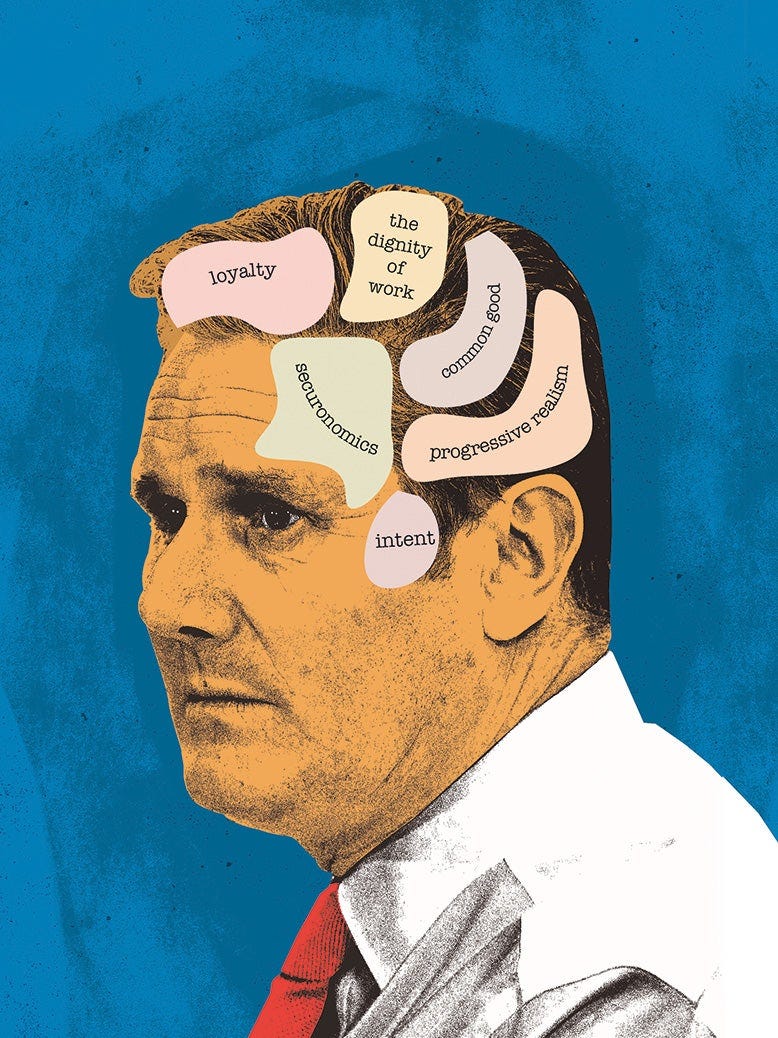

George Eaton returned to the parliamentary lobby for us this year to lead the New Statesman’s coverage of the Labour Party – its ideas, its people, its politics – as it prepares for power. This week he has written our cover story on what we think are the three big ideas behind Starmerism. But are we seeking an intellectual coherence in the Starmer project that perhaps even Labour itself does not recognise?

I had a quick chat with George about the concepts and values powering the next Labour government. You will find my conversation with him in the sign-off at the end of this week’s email – and click below to read his piece.

Another turbulent week at Holyrood – smartly analysed by our political editor, Andrew Marr – ended with John Swinney set to become the next first minister of Scotland. This is a case of Continuity Sturgeon: Swinney is a former (and failed) SNP leader and was deputy first minister from 2014 to 2023. If he does not address the changes many voters north of the border are seeking after a long period of complacent SNP misrule, then Scotland, as we argue in our Leader, may soon declare independence from the SNP.

It is notable that the SNP’s brightest talent, Kate Forbes, has declared her support for Swinney and will no doubt have a prominent role in his government. I spent some time talking to Forbes late last year for a long profile we published in our Christmas issue, “The rooted nomad”. Forbes is a politician of unusual interest and integrity and remains an SNP leader-in-waiting. She is surely the politician, in the post-Sturgeon era, who most unsettles unionists, for various reasons – her first-rate abilities, her charisma, her financial acumen, her ardent Christianity and her social conservatism.

Scotland under the SNP became more than a one-party state. It was a party-state: its leaders believed that the party’s interests were coterminous with those of the Scottish people. They were not – as the SNP has discovered to its cost. The independence movement has fragmented across three parties.

1—“Once something has been industrialised, it is also inevitably dehumanised.”

Ed Smith, the former Test cricketer and England national selector, takes us inside the fight for power roiling the world of golf. If you too have only followed from afar the story of LIV Golf, a Saudi-backed attempt to remake the sport, Ed explains all. HL

The PIF’s effect [the Public Investment Fund of Saudi Arabia] has been like watching sport’s uncertain relationship with money play out at x30 speed. In particular, its entry into golf – a sport that possesses the incendiary mix of liking big money but also perceiving itself as “gentlemanly” – was always going to be an epic clash of styles. Golf Wars, by the respected BBC golf correspondent Iain Carter, takes us inside his sport just as it is being split down the middle.

Breakaway leagues are always noisy, and usually more morally complex than a “good guys vs bad guys” narrative. Kerry Packer, the brash Australian whose World Series Cricket revolutionised the game in the 1970s, is a case in point. He waltzed into the Australian Cricket Board saying, “Come gentlemen, there’s a little bit of the whore in all of us; name your price.” But Packer saw his motives as half-altruistic. In the old way of doing things, the players weren’t getting a fair deal. After Packer, basically they have.

2—“We cannot put Gen P – the pick ’n’ mix generation – back in a box.”

Why is the general attitude in the West one of profound malaise when so much has improved in the past century? Gillian Tett asks whether a world of endless consumer choice has deepened the crises of democracy. PB

From the Renaissance on, Europe and then America began to get “Weird”, to use Henrich’s tag, meaning “Western, educated, industrialised, rich and democratic”. There was a Copernican shift in which human beings were seen as individuals that could exist separately from, or before, the social group; society was a derivative of people, not the other way round. This was reflected and reinforced by René Descartes’ “I think, therefore I am” philosophy, and the emergence of the concept of human “rights”. This trend intensified in the 20th century, producing the “Me” generation and Margaret Thatcher’s claim that “there is no such thing [as society]! There are individual men and women.”

3—“It was all I could do to keep myself from jumping out of my seat and crying out to her to stay home.”

We turned to Lee Siegel to make sense of the startling scenes playing out across US campuses. Lee’s pieces are always written in a different key to everyone else’s. GM

Israel is a beautiful, redemptive idea; Israel acts like a ruthless, amoral state. The pro-Palestinian protests are rooted in real, terrible injustice and suffering; they are fuelling an authoritarian right; they have been commandeered by people who think nothing of the shocking stupidity of having the students wear masks like the Hamas invaders who raped and butchered Israelis on 7 October. Protesting students are acting like feckless students; protesting students are the only people in society free enough to protest an ongoing mass slaughter.

The universities have misappropriated Said’s excoriations of scholarly malfeasance as admonitions against politically unacceptable speech altogether; the Republicans are threatening the universities’ independence, which is the lifeblood of a democracy; the universities have to be allowed to handle their own affairs; the universities are incapable of handling their own affairs. In 1968, everything converged. In 2024, nothing is aligned with anything else – even as everything is connected in some way.

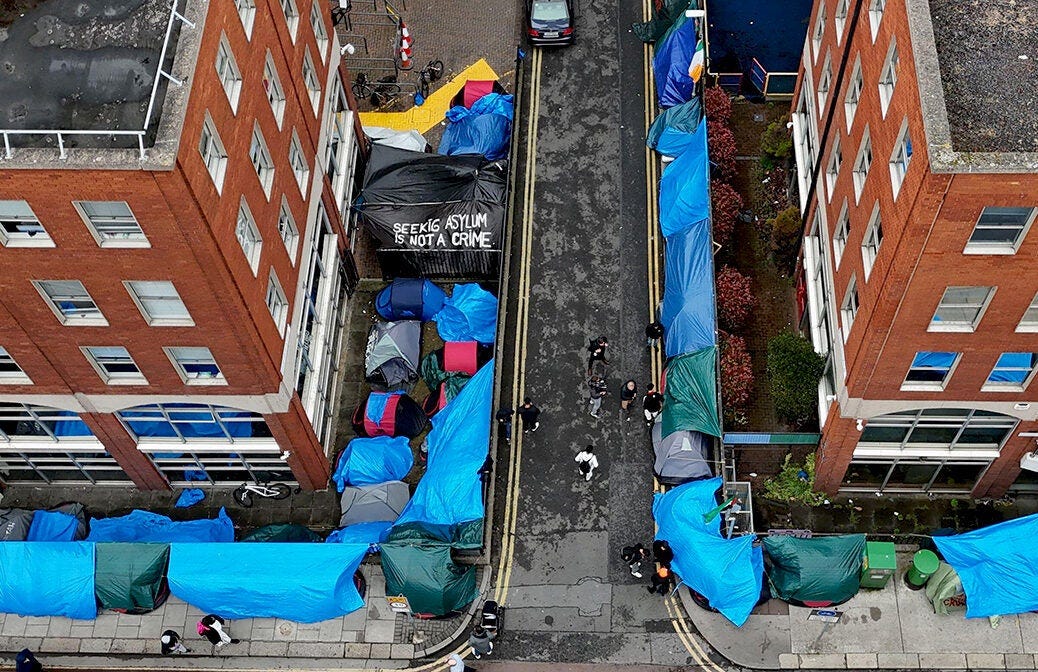

4—“The greatest trick Dublin ever played was dressing up its naked self-interest as an urgent moral issue.”

Compare the following remarks, both in our pages this week. David Gauke in his column: “In other words, Scotland is not that different from England.” Finn McRedmond in this piece: “In fact, the [Irish] government has begun to behave just like the Brexit Britain it so abhorred.” It seems we all stand alike, in the rubble of these beautiful islands. GM

All of a sudden that open border – insisted upon by Fine Gael as a matter of principle – doesn’t look and feel so good. With the government on the verge of deploying police officers to that border, it is hard not to notice the political inconsistency. Now that anti-immigrant sentiment is about to boil over and the political consequences will be felt in Dublin, it seems Ireland’s lofty principles in the Brexit years were more malleable than we were led to believe.

5—“Putin had a sense of humour once. He doesn’t seem to have it any more.”

George Robertson, the Labour peer and former secretary general of Nato, told Freddie this week that Vladimir Putin isn’t afraid of Nato, or Nato enlargement, but of the European Union. Robertson discussed his conversations with the Russian leader, and also reflected on his own notorious (and perhaps prescient) views on the SNP. PB

Whereas Putin, he went on, was “thin-skinned”, so “when Obama said that Russia was just another regional power [in 2014], that would cut through”. But Robertson views the UK and US’s failure to punish the Syrian president Bashar al-Assad for using chemical weapons in 2014 as the moment Putin realised he could act with impunity. “[It was] the most extraordinary thing to take place: a prime minister recalls the House of Commons in order to get backing for a military action… and gets defeated. And not only that, [he] then stays on,” he said. “In the Kremlin, that must have been a bright green light.”

6—“We are a lost generation.”

Is Gen Z as lonely as the statistics suggest? Is it because of rising social media and smartphone use, as Jonathan Haidt and others have argued, or is something else going on? In this arresting and disturbing piece, Sophie McBain spoke to the experts, and Gen Z, to find out. PB

Loneliness is a relatively modern phenomenon, the cultural historian Fay Bound Alberti observes in her 2019 book, A Biography of Loneliness. Until the 1800s loneliness was most frequently used to describe places that were unfrequented or remote, and if it was used to describe a person loneliness was seen as interchangeable with “loneliness”, a word that simply meant being physically alone. Only later did loneliness move inwards to become an emotional state, a feeling you could experience – sometimes most acutely – in a roomful of people. This idea of loneliness emerged as faith in an omnipresent, paternalistic God receded in the Victorian era, and as society transitioned from an agrarian, face-to-face society to an urban, industrialised one, alongside the growth of individualism.

7—“Every football club is a Ship of Theseus.”

Barney has reviewed Alex Duff’s history of Brentford Football Club, Smart Money. Upon its ascension to the Premier League, Brentford could not outspend other clubs. So it had to out-think them. Their thinker was Matthew Benham, a former banker and former gambler, who arrived at the club in 2012 with a unique way of thinking. GM

Smart Money, Alex Duff’s history of the club, ranges nimbly from the town’s sulphurous, Victorian peak, to bookmaker dens in Bangkok, to Sam Allardyce gulping down energy drinks in sweltering Florida. But his real star is Matthew Benham, the man who, after making his fortune in the City, and then through professional gambling, acquired a controlling share of the club in 2012. By instilling a reverence for data analysis and other statistical wonkery, Benham took Brentford from the muddy lowlands of the Football League to the shiny echelons of the Premier League.

George’s Best of the Rest

AP: Police clear Palestine protesters from Columbia University.

Alex Williams: Paul Auster dead at 77.

Joseph W Sullivan: The rise of the slacker aristocracy.

Juliana Geran Pilon: Liberalism hijacked.

Theodore Dalrymple: Orwell’s arresting ambiguities. We’ll just leave this here…

Time: How far would Trump go?

Tourist-hating Japan town builds screen to block its own view of Mount Fuji.

Sign-off: What is Starmerism?

Jason Cowley: George, you’ve written a very interesting reported essay this week on what we are calling Starmerism. But some say it’s too early to speak of “Starmerism”. The general view on the Labour leader is that he is a pragmatist and incremental social democrat. But you suggest there is more in play?

George Eaton: Thank you, Jason. My feeling is that there is more in play for two main reasons. First, because Starmer’s emphasis on the “dignity of work” and class – informed by his background – gives him a distinctive ethical and political position. It distinguishes him both from New Labour and from those who championed a British version of Emmanuel Macron’s En Marche.

Second, because of the world in which Starmer has become Labour leader: one in which the state has re-emerged as an economic actor and public ownership as a legitimate tool. Starmer has put politicians who have embraced these ideas, such as Rachel Reeves and Ed Miliband, at the heart of his project.

JC: But many politicians, especially on the left or in the Labour Party, have humble, working-class backgrounds. I agree about the return of the state, though: of a strategic state, but also of what we have long called a protective, even moral, state – in the efficacy and compensatory functions of the state to protect. How important is Rachel Reeves? I was with her in Washington DC last year, when she gave her first big “securonomics” speech.

GE: Reeves is pivotal. She spotted the return of the active state, and has fashioned it into a doctrine of her own. I thought the Mais Lecture, which she gave in March this year, was a good answer to the question of what a social-democratic agenda looks like in the 21st century. Starmer values her economic and intellectual acumen and her political experience: he doesn’t have an economics background and became an MP five years later than she did.

Reeves is a thoroughly Labour politician – as people such as Bernard Donoughue [director of policy for Harold Wilson and James Callaghan] recognise. She was never a fellow traveller of Change UK or Corbynism. Although it’s intriguing to remember that Andrew Fisher, Jeremy Corbyn’s head of policy, suggested she be appointed to the shadow cabinet on the grounds that she was “solid on the finances… and increasingly radical and in the same place [as Corbynites] on economic issues”.

JC: Is securonomics anything more than a form of protectionism in an age of geopolitical upheaval – or, as we and others have said, Bidenomics without the mighty dollar? Or does Reeves understand something fundamental about the world today?

GE: Reeves understands that, in a world in which the US, the EU and China have embraced forms of statism, the UK cannot stand apart. This requires her to reject the intellectual assumptions not only of Nigel Lawson’s chancellorship but of Gordon Brown’s (as she did in the Mais Lecture).

She also understands that economic growth is central to social democracy: it’s easier to share the cake if you’re also expanding it, and higher productivity is the only sustainable way to boost wages or you simply generate inflation. That’s a course correction. In the aftermath of the 2008 crash, the centre left became preoccupied with redistributing wealth rather than creating it (although Harry has also argued in our pages that Labour should redress taxation). Harold Wilson, who was an evangelist for growth, would appreciate this shift.

JC: David Lammy, the shadow foreign secretary, has a new concept which he popularised in a recent Foreign Affairs essay: “progressive realism”. We have long argued for realism in foreign affairs. But what of the progressivism? Are there echoes here of Robin Cook’s so-called ethical foreign policy that was swiftly undermined by events? After all, the world, as VS Naipaul writes in the famous opening sentence of A Bend in the River, is what it is…

GE: The progressivism is a commitment to causes such as human rights, international law and environmentalism. As you suggest, Lammy cites Cook as a lodestar but also the realist Ernest Bevin, Clement Attlee’s foreign secretary, who was pivotal to the creation of Nato and the nuclear deterrent.

Lammy believes that you can pursue realist means – engaging with countries such as China and Saudi Arabia, rather than treating them as pariahs – and achieve progressive ends: ambitious global agreements on climate change, a more peaceful Middle East.

JC: So the three pillars of Starmerism are the common good, securonomics and progressive realism. Does the project have such coherence or is the New Statesman creating it for them?

GE: The three pillars aren’t Labour’s own, although they were influenced by conversations with key aides, and I think you can draw illuminating links between them. Starmer’s ethics do inform Labour’s economics: the best example being the New Deal for Working People. The economics, in turn, inform the geopolitics: Lammy is clear about the foreign secretary’s role in promoting the active state.

Starmer is a pragmatist, so will govern according to the world as he finds it. But those decisions will be informed by his values and the intellectual currents within Labour – that’s the point of the piece.

If today’s pieces intrigued, you can subscribe to the New Statesman below. Stay up to date with everything from news and analysis to comment, criticism and essays.

Whether you’re looking for a sharp blog or a finely written feature, the New Statesman has you covered. Have a good week, and catch you next Saturday.

Yet again, I find I want to read everything. Well done!

Fascinating graph in the first paragraph re-news/electoral choices. I don't seem to be able to find the source, could you possibly share it ? Thanks