The Saturday Read: Built on sand

Inside: Rutte, Cruise, Carrie, Weil, Goodreads, and the search for Labour's ideas.

Good morning, and welcome to the Saturday Read, the New Statesman’s weekly guide to the best writing on ideas, politics, books and culture. This is Harry, along with Will.

Today’s Saturday Read has been sent, in scaled-down form, from abroad. We are away but the NS is not, so here are our ten picks for your weekend. The SR will return in full next week.

NB: If this email doesn’t load for you in its entirety, you can view it online (or in app) by clicking on the button you see when the email cuts off. The email hasn’t ended until you reach the sign-off. Today’s is on Disgrace, the JM Coetzee novel.

If the pieces below intrigue, perhaps you’d like to try a trial subscription to the NS. Read three free articles after registering on our site. A digital subscription is only 95p a week. If you are already a subscriber, thank you for reading us. Let’s get to it.

1—“Labour wants to rely on the old assumption that if you grow the economy everybody will grow with it. That has not been the case since the 1970s.”

George Eaton, our senior editor, has interviewed David Edgerton, a historian whose key work – The Rise and Fall of the British Nation (2018) – has currency in today’s Labour Party. Britain, he argues, has little hope of being in the front rank of nations any longer, and should stop acting as though it is. The horizons of our politicians need lowering, and focusing on “a politics of modesty and a politics of improvement”. HL

“We had a lot of talk not just about ‘Global Britain’ but about a ‘science superpower’, a real sense that the UK is not just a special nation by virtue of its history but that it is stuffed full of entrepreneurs. What’s happening now is a reaction to some of that; all of those promises have revealed themselves to be essentially false.”

For Edgerton, the danger of a melodramatic account of British failure is that it leads to deluded dreams of British rebirth. “It is an intellectually fatal position to take. Behind declinism is an appalling top-dog-ism: if we get it right we can regain our proper place in the world.

“The UK accounts for 2 per cent of global manufacturing and 2 per cent of global R&D. You’re not a science superpower if you do 2 per cent… You can’t go around claiming that in seven years’ time the UK is going to be a climate leader or a leader in green tech, it just doesn’t make sense.”

2—“In a 2013 public lecture Rutte said that he believed ‘vision is like an elephant that obstructs the view’.”

Megan Gibson, our international editor, explains how Mark Rutte – the Dutch prime minister since 2010, and the longest-serving head of government in the EU after Hungary’s Viktor Orbán – is finally to step down this autumn, his fourth coalition having come apart amid a crisis over refugee families. HL

Rutte presented as a moderate but was adept at channelling the forces of the nationalist populist right. His first coalition government, formed in 2010, relied on an outside support agreement with the Party for Freedom (PVV), led by the far-right, anti-Muslim Geert Wilders. But after Wilders pulled support in 2012, prompting the government’s collapse, Rutte shifted tactics; in later elections he ruled out partnering with Wilders.

To stop the far-right from peeling away votes from the VVD, Rutte instead adopted some of its rhetoric and positions as his own. Ahead of the 2017 election, Wilders borrowed his campaign slogan from Donald Trump: “Make Netherlands Great Again.” Rutte’s slogan was just as crude: “Act normal, or go away.”

3—“These are serious, dangerous times – more serious than the current feuding, elitist culture seems to appreciate.”

Britain’s summer of scandal is a tawdry sideshow that only the nation’s media-political elite are enjoying, argues Andrew Marr. While these decadent insiders have been gossiping about “poisoned pen” emails and the Sun’s controversial story about Huw Edwards, real problems remain outside their ability to solve, and grow ever more pressing. WL

Rishi Sunak’s five pledges – from halving inflation to stopping small boats in the Channel – are in disarray, and his party is too busy squabbling among itself to care. Keir Starmer has not yet translated his five missions into an overarching vision for post-Brexit Britain. Where there should be a vigorous and urgent debate about our nation’s future there is a void. Scandal is filling it.

Sign up here to our daily political newsletter, sent Monday through Friday:

4—“Ours is a world both objectively and figuratively built on sand.”

We think the world now depends on software – writes Will Dunn in his review of Ed Conway’s new book, Material World – because it is the interface through which we all now work and live online, but “in reality we live, as previous generations did, in an economy of oil, glass, steel and sand”. (Will D also has an interesting interview out today.) HL

Humanity has taken the most basic, widely available material and refined it into everything from skyscrapers to components smaller than the wavelength of visible light. In doing so we have created a new kind of instability. The more advanced our technology becomes, the more specialised the facilities needed to produce it, such that there now exists a small number of mines, factories and labs on which the whole teetering edifice of modern capitalism depends.

Choke points, as they are known in the supply-chain world, are everywhere: each one carries the risk of disruption, inflation and recession. Some are geopolitical in nature: Taiwan, where TSMC creates the world’s semiconductors, considers itself an independent territory, but China, which is years behind on chip-making, disagrees.

5—“The budget of Mission: Impossible – Dead Reckoning Part One is $290m, seemingly spent on blowing up a bridge.”

I remember watching Mission: Impossible 2 in 2001. Aged nine, I picked it out at Blockbuster on a Friday night with my dad, to celebrate moving to a new school. Twenty-two years later, Tom Cruise is still going. Ann Manov wishes he wasn’t. HL

Everything about Mission: Impossible – Dead Reckoning Part One is larger than life. With a thin plot filled out by half-hour chase sequences, the film is 163 minutes long: even at the press screening, people were checking their phones. Richard Wagner’s 1874 Ring cycle totals about 15 hours of music. If Dead Reckoning Part Two is the same length as Part One, the Mission: Impossible franchise will soon exceed the Romantic masterpiece in length. And Tom Cruise has assured us Ethan Hunt is not finished yet.

From our sponsor

And, not or. We’re investing in today’s energy system and the transition to lower carbon energy. So whilst we keep oil & gas flowing from the North Sea, we’re also designing two hydrogen plants intended to reduce emissions, helping create & protect jobs. Explore these projects and more.

6—“Truly, it’s biblical: the horror, the foreboding.”

Rachel Cooke, our TV critic, reviews the latest series of Sex in the City, the show that won’t die. It was good once! HL

The boxes of race and gender having been ticked courtesy of new characters and Charlotte’s trans child, it’s full steam ahead with late capitalism. Put Trump, DeSantis and all the others out of your mind, and enjoy instead – so funny, so cute – the spectacle of Charlotte haggling over a child’s Chanel dress; of Carrie making a six-figure donation to a non-existent magazine purely to assuage her embarrassment over a dick pic; of Lisa (Nicole Ari Parker) and her husband accidentally wasting thousands of dollars on a dinner that will never be eaten.

7—“There was nothing Weil despised more fiercely than seeking refuge in grand terminology that promised salvation.”

War and peace, suffering and salvation, experience and ideology – the thought of Simone Weil, writes Wolfram Eilenberger, has never been more relevant, or seemed more radical. WL

For Weil, we are beings moved to action not, in the first instance, by concepts but by forces beyond ourselves: experiences of suffering, love, profound insight or disturbance, whose origins Weil did not shy away from calling transcendent, even divine. Weil believed that true awakening can be achieved only when we find within ourselves the necessary stillness, the necessary weakness, to move on from the world of conceptual thought.

8—“Labour is again resorting to the language of feelings.”

One slightly worrying joke that makes its way around Westminster from time to time is: Keir Starmer does not understand economics. (Less a joke, more a morbid punchline.) In her debut column for the magazine, Ashley Frawley considers what happens to a party that has no idea what to do with Britain’s ailing economy. The answer lies in attempting to maintain and engineer what the late JG Ballard called “inner space”. WL

But Starmer’s education speech was symptomatic of a deeper malaise. Having given up on exerting control over the economy or their economic lives, subjects can only be “resilient” to whatever exogenous shocks transpire around them. The message of Brexit was “take back control”. The dominant political message today is, “we can’t control”. We just have to be “resilient” to a world beyond our control. This is the dark, unspoken side of securonomics.

9—“Britain is the only major European state that is expecting a significant electoral swing to the left.”

After Brexit, Britain was supposed to become a nation in the mould of Philip Larkin: wintry, xenophobic, and stranded in its own dark interiors. Yet here we are barely a decade later, says Philip Cunliffe, with Labour about to assume power and the continent lurching further and further to the national populist right. WL

As difficult as it might be to countenance, British liberals and leftists have to reckon with the fact that it is Brexit that has given Britain the opportunity to escape the populist vortex engulfing Europe. While liberals have tended to see Brexit as a populist insurrection led by charismatic and mendacious figures such as Boris Johnson and Nigel Farage, Brexit was in truth always larger than any party or single leader – which is why it has survived both of them. Far from stimulating populism, Brexit destroyed it, torpedoing both Ukip and the Brexit Party, by removing their sole reason for existing.

10—“Why does the word ‘Goodreads’ summon in me a creeping feeling of dread and nausea?”

In the world of books, Megan Nolan explains, Goodreads is almighty – a combination of Twitter, Facebook and Instagram. The site allows users to log what books they read, then rate and review them. Goodreads is now, from the writer’s perspective, an inescapable nightmare. WL

I had scarcely heard of Goodreads prior to writing a novel, but when my first book was published, I was warned of it in ominous tones by every novelist I met. I first looked at my page in the winter of 2020, months before my debut novel came out. The very first proof copy had arrived at my house that day; nobody but me and the publisher had seen it. Despite this, it had received one review already: two stars, left by someone I had inconsequential personal discord with. It was completely impossible for him to have read the book.

And with that…

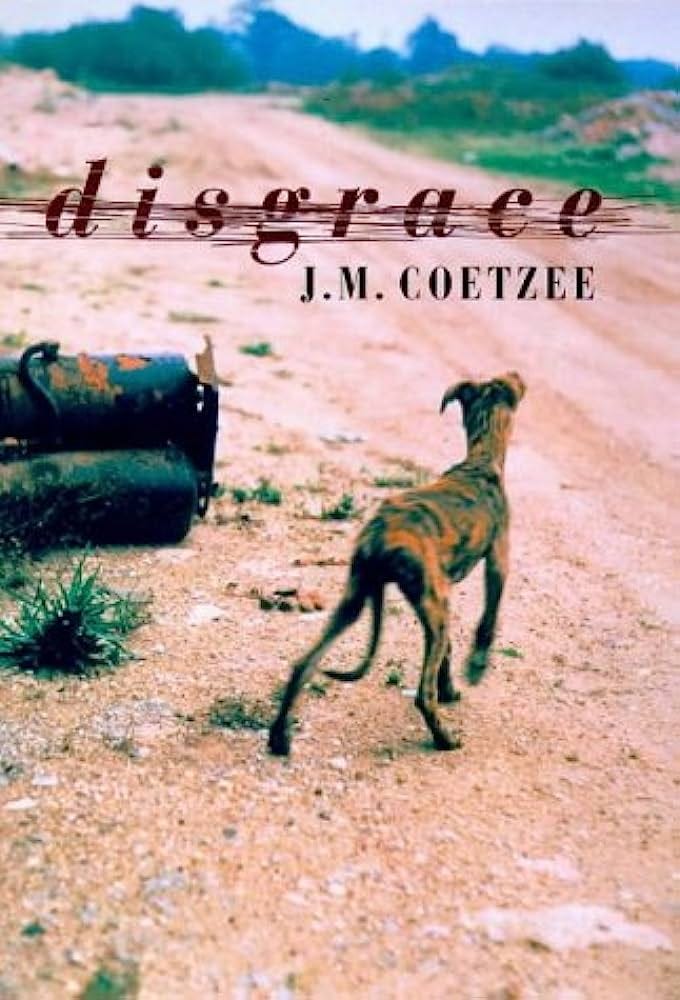

“For a man of his age, fifty-two, divorced, he has, to his mind, solved the problem of sex rather well.” So begins Disgrace (1999), JM Coetzee’s best known book. Jason, our editor-in-chief, described it in 2001 as that rare novel which brought “urgent news of our times”. Leo Robson, also in our pages, labelled it an atypical “albatross” in Coetzee’s oeuvre 20 years later. It was selected as the greatest novel of the past 25 years in a poll by the Observer of 120 literary critics in 2006. It won Coetzee the Booker Prize for the second time and the Nobel Prize in Literature shortly after its release.

So is it any good? Thankfully I did not know of its standing when I opened it. I just knew that my grandmother, who is South African like Coetzee, had told me to read it years ago. I picked it up in a house last weekend. It is brief – 220 pages – and reads even quicker.

There are moments when the book doesn’t work: when the characters ventriloquise Coetzee’s allegorical thoughts rather than speaking in words as fractured as the situation they find themselves in, and when Coetzee gets lost in the book’s juvenile B-plot – its protagonist’s abortive bid to write an opera centred around Byron. But Disgrace is propelled by scenes you won’t forget.

The man of 52 to whom we are introduced is a professor whose solution to the “problem of sex” unravels page by page. First he pursues one of his students. Then his daughter is pursued. Will thinks the professor is changed by disgrace. I thought his delusions remained in tact as his world collapsed.

These are the kind of sentences you will be left with: “Not rape, not quite that, but undesired nevertheless, undesired to the core. As though she had decided to go slack, die within herself for the duration, like a rabbit when the jaws of the fox close on its neck. So that everything done to her might be done, as it were, far away.”

Thank you for reading. Don’t miss out – subscribe to the New Statesman and stay up to date with everything you need: from news and analysis to comment and criticism.

Whether you’re looking for a sharp blog or a finely written feature, the New Statesman has you covered. Have a good week, and catch you next Saturday.

Thanks to our colleague Chris Bourn.

I enjoy your email every week and subscribe to the NS.

Edgerton is over stating. We do have DeepMind and the covid vaccine and an advantage on AI regulation. Not bad for such a small country!

Also London’s not exactly devoid of entrepreneurs...