The Saturday Read: Capital reigns

Inside: Taxing wealth, reversing modernity, food as status, and were the realists right?

Good morning, and welcome to the Saturday Read, the New Statesman’s weekly guide to the best writing on ideas, politics, books and culture. This is Will. We have lost Harry this week to the Mediterranean. Freddie has stepped in.

This week I’ve interviewed the MP Danny Kruger (see below) and the philosopher John Gray (out soon). I’m writing this on a train to Scotland to interview another, well, sort of Conservative. We have just left Berwick-upon-Tweed station, a name guaranteed to make Americans laugh, and also a stop along one of the great train lines in Britain, dramatically parallel to the North Sea. There appear to be more seagulls than people up here.

If today’s pieces intrigue, perhaps you’d like to try a trial subscription to the NS. Read three free articles after registering on our site. A digital subscription is only 95p a week. Let’s get to it.

1—“The wealth of the very richest is boundless yet bound in by Britain.”

The political question of the moment is what Labour would do with victory. Rachel Reeves, the shadow chancellor, has categorically ruled out taxing wealth. In this week’s cover story, Harry argues she is wrong. FH

Labour is ignoring wealth at its peril. Reeves is rejecting the most consequential tax reforms open to her, despite polling that suggests each reform she has ruled out would be highly popular. They are also vital. Britain’s growth rate is in a multi-decade decline, while wealth inequality has become entrenched. It hasn’t fallen in the 17 years the Office for National Statistics has recorded it. Every year you can expect £4 in every £10 of new wealth to go to the wealthiest 10 per cent, while £1 in £10 is shared by the bottom half. In stagnant societies, capital reigns.

The Tories have lost credibility, gifting Labour a generational opportunity to be heard. There is no better story Starmer could tell than the story of tax: who it serves, who it exploits, and how it could be fixed.

2—“Modernity has brought little but ruin to Britain.”

There are few Tory MPs as secure in their beliefs as Danny Kruger. He has emerged as a figurehead for the National Conservative wing of the party – an amalgam of those who want lower immigration and long for traditional values. Has Will returned from this interview with a letter from the Conservative Party’s future? FH

Danny Kruger MP was pondering when the best time to be British was. We were sitting in a living room at his home in Wilcot, Wiltshire. Around us: a cello, a cricket bat, portraits, books, bottles and half-empty glasses. So much posh clutter. “The best time to be alive,” said Kruger, “if you were healthy and wealthy was the late 18th century.” It’s not a struggle to imagine Kruger in a top hat, clutching a cane or complaining about Pitt the Younger in a tavern. “To be a healthy English gentleman in 18th-century England was as good as it gets.”

England is in decline. That is one of the messages of the Conservative MP’s trenchant new book, Covenant: The New Politics of Home, Neighbourhood and Nation. The book, and much of what Kruger says publicly, is influenced by the philosopher Alasdair MacIntyre, the theologian John Milbank and the late Roger Scruton. Kruger, an evangelical Christian since his wife gave him a copy of CS Lewis’s Mere Christianity when he was 28, has built a reputation as one of the most Tory Tories in the House of Commons, which he joined in 2019.

3—“The breathless hype that characterised early media coverage has curdled into doom.”

As the counteroffensive falters, the West appears to be falling out of love with Ukraine and Volodymyr Zelensky. The signs from Washington, argues Lily Lynch, are ominous. Western support for this war may have been more conditional than it first seemed. WL

The deadlock has increasingly resembled brutal, unabating, First World War-style combat, with the Ukrainian army rapidly depleting artillery ammunition supplied by the West. Distant audiences, who always treated the war as a team sport, and Ukraine as an underdog defying the odds against a larger aggressor, are thinning out; surely many will soon turn their attention to the partisan conflict of the forthcoming US presidential election. Optimists say the change in the media’s tone is indicative of little more than the inevitable pendulum swings of war and that Ukraine may yet emerge victorious. But such a view elides a host of unavoidable realities.

4—“Before he wrote history, EP Thompson made it.”

This week marked the 30th anniversary of EP Thompson’s death. Thompson still is principally known today for The Making of The English Working Class (1963). But as Madoc Cairns explains, Thompson’s life was, if anything, as compelling as his work. WL

For all Thompson’s professed materialism, he never wavered in his conviction that history is not just a record of action but a means of exchange, a place of meeting: deep underneath the earth we walk on, in places the powerful never consider and the cynics can never reach, course underground rivers of struggle, friendship, justice, love. And that there are times in history when “the stored energies of the dead flow back into the living”, when those forgotten rivers burst to earth. Thompson didn’t know if he was living in such time. But the hour was late. For four decades he’d fought and lost. The treaties had been abrogated; the powers were gearing for war – a war, many analysts thought, that would come quickly, and leave nothing behind. He had to try.

What your organisation needs to combat modern cyber threats

Hybrid working has brought new challenges for securing networks. But investing in good software can ensure businesses are safer than ever before.

5—“Vittles asks the urgent question: what if we went to Edmonton for dinner?”

Food is not about what appears on your plate, says Finn McRedmond. In fact, when it comes to restaurants, status matters more than taste. London food criticism has been changed in recent years by Vittles, a politically charged newsletter dedicated to out-of-the-way eateries, hole-in-the-wall kitchens and food vans. Vittles is not quite what it seems. WL

Pinballing around London, Vittles guide in hand, in search of undiscovered culinary gems is about as bourgeois as it gets. But somehow the loyal proponents of Vittles… have adopted a patina of class activism: no better way to demonstrate the right kind of thinking than trading Covent Garden for Tottenham Hale. Of course foodie-ism suffers a dearth of legitimate diversity; for too long it has been the preserve of the elite. A course correction is welcome. But at the end of the day going to Enfield for breakfast just because you can is about as middle class as it gets. Eating dosa is not political.

6—“For every internal border removed an external border has been fortified.”

The barrister Marina Wheeler reviews Eurowhiteness, a new book by Hans Kundnani that challenges Europe’s self-conception. The European project is built on myths, Kundnani claims. The EU was never merely about preventing war; it was about power. Binding the continent together also meant shutting out the rest of the world. FH

When I was a pupil at the European School in Brussels I learned that the point of the European project was to make war between France and Germany “not merely unthinkable but materially impossible”. But, writes Kundnani, European countries did not reject war after 1945. They rejected it within Europe; outside it they continued fighting colonial wars until they were spent or defeated. On 8 May 1945, the day Europe celebrated peace, French forces were suppressing Algerian independence with a massacre at Sétif and Guelma.

Astonishingly, when the Treaty of Rome was signed in 1957 to create the European Economic Community (EEC), France and Belgium’s colonial possessions were included, meaning most EEC territory was in Africa, not Europe. Free movement didn’t apply, but the treaty let France and Belgium consolidate colonies they could not have maintained on their own. At the same time many of the EU’s founding fathers signed up to a revived idea of “Eurafrica” – a movement to modernise Africa and access raw materials.

7—“It’s no coincidence that crypto’s rise happened in the wake of the 2008 financial crisis.”

In the US, the cryptocurrency boom was driven by advertising featuring Hollywood actors. Unlike some of his colleagues in Los Angeles, Ben McKenzie – that’s Ryan from The OC – is also a trenchant critic of digital currencies. He told Megan Gibson why they’re a scam in our Weekend Interview. WL

Though McKenzie is openly critical of the celebrities who have pushed these products, he lays ultimate blame on the sluggish regulators that allowed it to happen. “I think in many cases the celebrities didn’t really understand what they were selling. Which is not to absolve them of a moral, ethical [or] potentially even legal responsibility for their actions. But they don’t need to be bad people – they just see easy money, right?”

8—“It is so boldly different it creates a mini-genre all of its own.”

The resuscitation of Theresa May’s reputation marches on. The former prime minister has inverted the genre of memoir in her new book The Abuse of Power, argues Andrew Marr. Gone are the self-pitying excuses found in most books of this type, and in comes a call for those in power to act with integrity. The result, Andrew writes, is bold and unexpected. FH

Theresa May’s roll-call of failure’s victims is horrendous. There are the 97 victims of the Hillsborough disaster, cover-up and smear. There is the uncountable number of scarred women and badly malformed babies from the pregnancy-testing drug Primodos; the 72 dead at Grenfell; the estimated 3.1 million British adults who suffered sexual abuse as children; the 1,400 abused children in Rotherham; the 122,000 people said to be living in modern slavery in Britain; the victims of the Windrush scandal; the family of the murdered Daniel Morgan; the 27,000 recipients of unlawful stop-and-search police interventions in a single year… and many more.

Plainly written, sourced almost entirely from official enquiries, and deficient in quotable character assassinations, this is a serious book by a serious woman.

Will’s Best of the Rest

FT: One year in a struggling British school. A brilliantly illuminating longread.

Times: Nadhim Zahawi helping Barclays regain Telegraph in UAE.

Wired: Preferring biological children is immoral. The term for this is “one hell of a take”.

Atlantic: The real men South of Richmond.

Christian Lorentzen: Don DeLillo’s systems.

Caitlin Flanagan: Not all masculinity is toxic. Tell my mother that!

Tajja Isen: Goodreads is awful for books.

Pankaj Mishra: “Brics” is a meaningless acronym.

Christopher Caldwell: The general who defied Meloni.

LinkedIn is “weirdly personal” now. Does anybody know why they are on LinkedIn?

ChatGPT’s popularity wanes. Maybe it’s boring to have your work done for you by a machine?

Elsewhere on the NS

Prigozhin’s death was not a victory for Putin, argues Lawrence Freedman. Caution, sloth and apathy will continue to reign among the Russian military fighting in Ukraine, whatever happens in Moscow.

How will that conflict end? Wolfgang Münchau looks at the historical record, and suggests that it offers slim hope for a decisive Ukrainian victory.

Charlotte Stroud gets stuck in a cupboard and finds more than she bargained for inside.

Britain’s petit bourgeoisie are seriously misunderstood, says Dan Evans. But they have become the subject of the nation’s most popular meme: Deano.

Donald Trump’s return to Twitter – sorry, X – is less a victory for the 45th President and more a confirmation that he’s just another creature in Elon Musk’s circus. Sohrab Ahmari thinks the platform was better when it was run by the left.

Bruno Maçães interviews Representative Don Bacon, a Republican congressman from Nebraska, on whether the US will keep sending financial aid to Ukraine.

Lewis Goodall breaks down the myth that Britain is at war with motorists: “Car owners are in fact likely to be richer, older and of greater social status, though we rarely hear that expressed. It is often the poor and the young who rely on public transport, if it exists, but how often are they part of the conversation?”

“We lack the ability to conversationally differentiate between porn as it has classically been known and the internet addiction that defines it at present.” A gem of an essay on pornography and Camille Paglia from Magdalene Taylor.

How to get into: Cities

Each week we ask someone to recommend three books as a way into a subject. This week we turned to Megan Gibson, our international editor. She offers her guides to understanding the city, the place where the politics of the age invariably plays out.

The Death and Life of Great American Cities by Jane Jacobs (1961): Read this not only for Jacobs’ ideas – on the sidewalks, parks and neighbourhoods that make cities work – but the writing, which is a pleasure, filled with description, character, and bite. Jacobs, writing at a time of large-scale modernist projects, casts both heroes and villains in her classic work. Robert Moses, New York’s most influential planner, does not come off well.

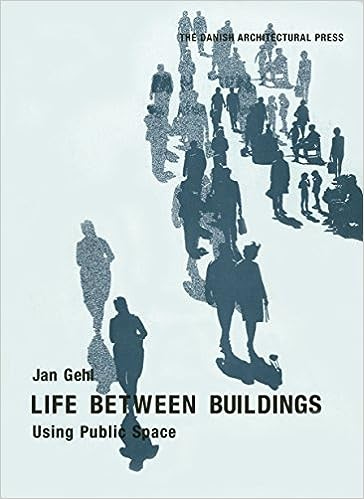

Life Between Buildings by Jan Gehl (1971): Reshape cities in favour of pedestrians and cyclists, argues Gehl. The city isn’t made for its buildings; it’s made for its people.

Municipal Dreams: The Rise and Fall of Council Housing by John Boughton (2018): Written in the wake of Grenfell, this narrative history captures how the ideal of the council home was undermined in the UK over decades by both parties.

Thank you for reading. Don’t miss out – subscribe to the New Statesman and stay up to date with everything you need: from news and analysis to comment and criticism.

Whether you’re looking for a sharp blog or a finely written feature, the New Statesman has you covered. Have a good week, and catch you next Saturday.

Thanks to Chris Bourn and Freddie Hayward.