The Saturday Read: Christmas Special II

Inside: Assad and Putin, America’s counter-elites, Paul McCartney, Michael Prodger on Handel, John Bew, Sven-Göran Eriksson, and where the Democrats go next.

Good morning. Welcome to the Saturday Read, the New Statesman’s guide to politics, culture, books, and ideas. This Finn together with Nicholas, Pippa and George.

While compiling our best stuff for you this week we noticed a preponderance of Johns. Philosopher John Gray, historian/former No 10 adviser John Bew and author John Banville all write for us this week. While John Simpson of the BBC and John Lennon provide some great subject material.

This is the last you will here from me, Nicholas, George and Pippa this year. For the closing Saturday Read of 2024 (next week’s edition), the New Statesman’s outgoing editor-in-chief, Jason Cowley, returns a final time. He has picked his ten favourite pieces published over his entire 16-year tenure.

Before then, George, Pippa, Nicholas and I just want to give a warm thanks to all of our writers – Johns and non-Johns – to the now 225,000 of you who subscribe to the Saturday Read, and to all our thoughtful and funny commenters. We will be back in the New Year, ready to peer into the American right and to ask whether 2025 is finally time for British politics to put the pipe down. Stay tuned and see you next week for Jason’s picks, 2008-present. As ever, thanks for reading.

The picks…

Good morning and Merry Christmas, Nicholas here. A spirited debate over Christmas No 1s in the office this week prompted Michael Prodger, our wisest and most owlish colleague, to nominate Handel’s Messiah. He discusses the original Christmas single below. Meanwhile, Leo Robson and Helen Thompson return to our pages, and Freddie signs us off with some tentative guidance for the American left in the new year. Have a great week – and a restful December.

1—“Globalisation’s retreat”

The American election was a fight between rival oligarchies: the elites (Bill Gates is their standard bearer) and the counter elites (think Elon Musk and Peter Thiel). This decisive shift away from the Democrat establishment, John Gray argues, is proof that progressive hegemony is ending. FMcR

It would nonetheless be mistaken to interpret the behaviour of these oligarchs as serving only their financial self-interest. To a considerable extent, they were reacting against a threat posed to an idea of America. Apparent collusion between the Biden administration and some big tech companies in attempting to stifle free speech in social media offended an image of themselves as enjoying a quintessentially American freedom. Above all, it was the extravagant sense of entitlement of the liberal classes, with their ill-concealed disdain for the values of much of the population, that enabled the right to mount its counter-revolution. Trump’s elites have their own ideologies, but they are more pliable than the rigid constructions of hyper-liberals, and their contradictions match those of American life.

2—“Russia’s prized foothold”

The Kremlin is attempting to play down the consequences of Assad’s fall in Syria. In truth Russia has suffered a serious strategic loss. But how much does it matter? Putin is closer than ever to victory in Ukraine, Katie Stallard suggests. FMcR

Still, this does not mean that all is now lost from the Kremlin’s perspective. Putin will seek to preserve his options for future negotiations, content to allow Assad to live, quietly, under his protection as he endeavours to retain what leverage he has, well aware of how rapidly the region’s past popular uprisings have descended into violence and renewed civil war. He will also be even more focused on his own regime security, having seen how quickly his Syrian counterpart’s grip on power evaporated. But above all else, Putin is likely to be even more determined to press ahead with his assault on Ukraine, where he believes his forces are now winning on the battlefield and a meaningful victory is finally within his grasp.

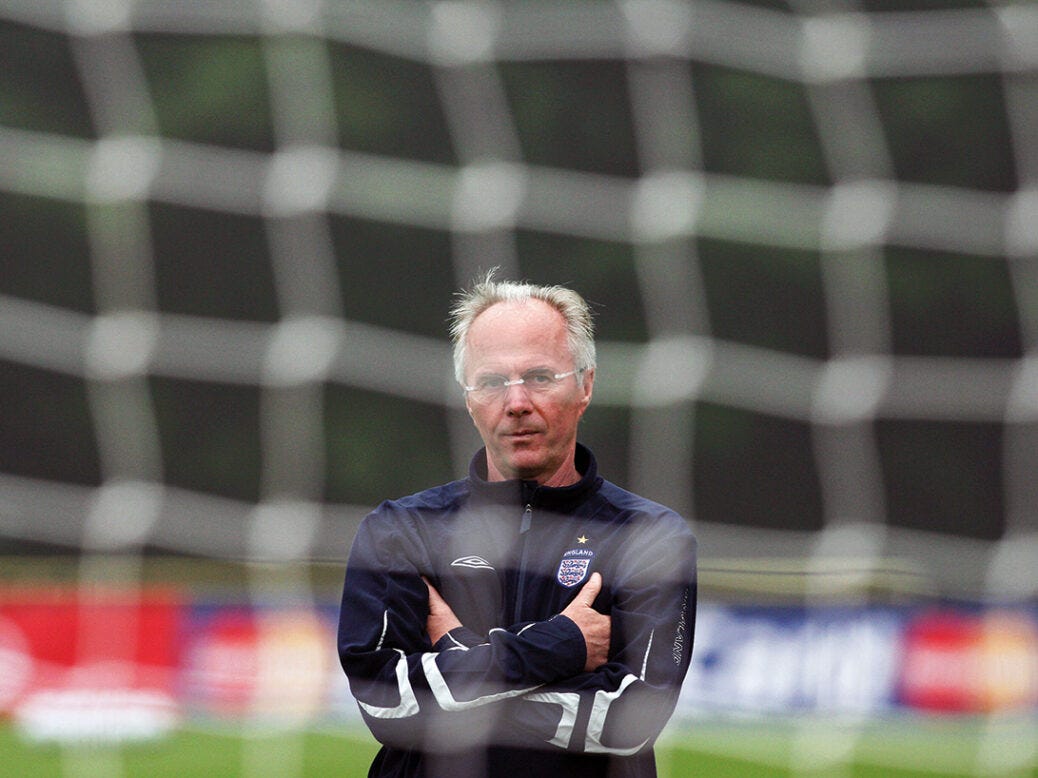

3—“The best apprenticeship for death”

Football provided the late Sven-Göran Eriksson with a particular stoicism as he reached the end of his life. In this review of the former England manager’s posthumous memoir, Leo Robson elucidates the dilemmas of Eriksson’s career – and an entire footballing era. NH

Eriksson was a victim of bad luck. He took charge of England for two World Cups and a European Championships. Before the first, Beckham broke a metatarsal; before the third, Wayne Rooney did… It’s also unclear that the Golden Generation were really golden at the same time. Michael Owen was more or less finished and Beckham had taken up his semi-retirement gig in Los Angeles before Rooney marked his 22nd birthday. The boring truth may be that whereas Eriksson had a lot of world-class talent to work with, it didn’t quite suit a diamond, a Christmas tree, or any other viable formation. That’s the curse of international management: you can’t recruit players.

4—“Too much, too quickly”

Crossing the globe and labouring to advance Shakespeare, Johnson and Joyce, Anthony Burgess wrote and lived enormously. John Banville tells us of his rich life and then of a lesser-known work that features “Promethapoleon” – yes, Napoleon as Prometheus. Who could say no? GM

In 1942 he married Llewela, or Lynne, Jones – tempestuous, intelligent and sexually liberated. The Burgesses’ marriage was a raucous affair. Lynne was a public drunk, and often got into fist fights in pubs or on the street. Her husband too was no slouch when it came to roughhousing. One of his biographers, Andrew Biswell, reports him at the age of 50 losing four of his lower front teeth in a pub fight in Chiswick with an Irishman who had insulted his dog.

5—“Condemned to disappoint”

For years – decades – John Lennon was considered the major Beatle and Paul McCartney the naïf, populist collaborator. Now McCartney is rightly heralded as the greater talent. Taking a break from industrial strategy, Helen Thompson unpacks his life and career. NH

If McCartney cares too much about the Beatles to compete in the performance of truth-teller, he will also not conform to the role of the artist. Melvyn Bragg once perceptively said that the 1970s McCartney had made a “magnificent attempt to be seen as, and to behave as, a very ordinary young English man” to hide the fact that “he was a most extraordinary young English man”. But in the classical compositions, the electronic music as the Fireman, the poems, the “Eyes of the Storm” photographic retrospective, and the painting exhibitions he has offered since the 1990s, McCartney’s artistic imagination has become conspicuous.

To enjoy our latest analysis of politics, news and events, in addition to world-class literary and cultural reviews, click here to subscribe to the New Statesman. You'll enjoy all of the New Statesman's online content, ad-free podcasts and invitations to NS events.

Centuries before the charity Christmas single came Handel’s Messiah. The composition was not, however, written as a seasonal work but covered the life of Christ from the Nativity through to the Passion and the Resurrection. Its first public performance was in Dublin on 13 April 1742 and its London premiere came a year later. Handel stipulated that he would never take money from the performances, or any subsequent stagings, but that all receipts should be donated to charity. The reason for this largesse, according to the Jewish novelist, journalist and librettist Stefan Zweig, was gratitude to God.

In 1927 Zweig wrote a series of “historical miniatures”, one of which was a vivid recreation of Handel at work. We published the piece in the magazine in 2014. Zweig recounts how Handel recovered from partial paralysis, debt, depression and composer’s block to write the Messiah in a fit of pure inspiration: “Tears blurred Handel’s eyes, so mighty was the fervour in him. Hastily, he picked up his pen and began setting down notes. He could not stop. It carried him away, like a ship with all sails spread, running before a stormy wind.” The work quickly became beloved by both performers and listeners, and it was the composer’s favourite too. In 1759, “severely ill and 74 years old, he had himself led to the podium of Covent Garden once more” for a final rendition. He died a week later, on 13 April, 17 years to the day since the world first “heard a work of music… such as had never been heard on Earth”.

6—“Indecisive nature”

In 1901-2, William James (the elder brother of the novelist Henry James) gave a popular series of lectures: “The Varieties of Religious Experience”. They covered mysticism, conversion, saintliness and more. It was the “leakiness” of James’s mind, writes Lamorna Ash, that made him open to such varieties. PB

In a letter from 1904, William James suggested that, though he himself had “no living sense of commerce with a God”, still “there is something in me which makes response when I hear utterances from that quarter made by others. I recognise the deeper voice. Something tells me: ‘thither lies truth’.” Through Varieties, I came to understand that with religious experiences the useful question was not “How can you believe that happened?” but “What has such belief done to you?”. “By their fruits ye shall know them, not by their roots,” James explains in the first lecture, reappropriating a line spoken by Christ in Matthew’s Gospel. His approach is that of an empiricist, a pragmatist (the movement “he largely created”, Menand suggests, together with the philosopher Charles Sanders Peirce). “I might multiply cases almost indefinitely,” he informs his audience, “but these will suffice to show you how real, definite, and memorable an event a sudden conversion may be to him who has the experience”.

7—“Engaged, devastated, comforted, invigorated”

It’s become commonplace to wonder whether the novel is still a valuable and relevant literary form. In an essay adapted from the New Statesman’s Goldsmiths Prize Lecture, Deborah Levy answers head on. Does the novel matter? Of course it does, duh! FMcR

During my father’s dying days he summoned me to his sick bed and requested I find a pen and paper. I believed that, at last, he was going to express his wishes for his funeral and its various rituals. In fact, he wanted to dictate a menu for the week. It turned out that he was not satisfied with his meals. For Tuesday he suggested fish curry, Thursday lamb chops, Friday roast chicken. My father was 91, fatally ill and could only swallow liquids. By the time he reached Saturday, I began to admire his bid to be alive for a whole week (unlikely) and to live imaginatively to the very end.

I understood that he was struggling with too much reality (imminent death) and needed a break. I accepted his language, and did not pierce it with a literal reply such as: “But you can only swallow thin soup.” We both knew this anyway. The various ways we negotiate with reality are at the core of all writing and living.

8—“He still has no nightmares”

At 80, John Simpson has been world affairs editor at the BBC for 36 years. He sat down with Kate Mossman over a double whisky at Broadcasting House to talk about his favourite dictators, how Tony Blair ruined the BBC, and why Putin is “not a madman”. PB

When he watched three botched hangings by the Mujahedin in Kabul, he thought he would never sleep again – but he wrote about it all in the Sunday Telegraph, dictating every detail to “a lovely motherly copy-taker” who said, “Oh you poor thing,” at the end of the call: the men have never featured in his dreams. He was tortured in Beirut in 1982: he will not say what was done to his body, but they followed with a mock execution – a gun detonated against his head, which turned out not to be loaded, then a handshake when he got off his knees. He had a crisis of confidence after that, because he realised he would talk under pressure: the only thing that stopped a confession was the state of his torturers’ English. “A terrible blow to my self-esteem. Realising that you’re not dying on the cross for all of this as you thought you were.”

9—“The raw power game”

Following the historian John Bew’s departure from government, he returned to the pages of the New Statesman with an extraordinary essay on foreign policy, idealism and the historical moment. As a true tour d’horizon, the piece even finds space for Flaubert. NH

We need a statecraft that goes beyond the maintenance of a rules-based international system, which has been the main business of our foreign policy for many years. That work remains vital, of course, and it matters deeply to the future of Ukraine and other parts of the world where revisionism risks global instability on a scale that surpasses anything we have yet seen. But we must be able to walk and chew gum with a bit of spaghetti-western swagger. And so the national interest of the UK – which I would define as improving the security, and social and economic life of the British people – requires us to get down to work to seek hard economic and security outcomes, rather than the sentimental education of those whose world-view does not exist in perfect sympathy with our own.

10—“Taylor lost. Oprah lost. Beyoncé lost”

Right up until Donald Trump’s win – the first popular-vote victory for a Republican in 20 years – people still thought Hollywood could drive votes. In an exciting NS debut, Ross Barkan explains how the bien pensant celebrity elite has lost power. GM

Throughout 2022, 2023 and well into 2024, party elites, prestige journalists and Democrat-aligned celebrities all insisted that the octogenarian Biden, noticeably fading, was fit to run for a second term. It took the greatest emperor-has-no-clothes moment in modern American history – a TV debate with Trump in which Biden struggled to finish sentences – for reality to finally set in. Millions of Americans began to wonder why they had been lied to.

Harris’s ascension, without a single vote cast for her in a Democratic primary, was also waved away. The celebrities sang for her. Following the DNC, to question her flailing campaign – to wonder why she was not talking more to traditional or alternative media, or demand she put forth a genuine policy platform – was to be labelled an apostate or a Trump booster.

George’s Best of the Rest

Charlie Warzel: Luigi Mangione has to mean something

Rana Foroohar: Europeans need to learn some lessons about power – and fast

Paul Krugman: My last column

Mattia Ferraresi: Giorgia Meloni is Trump’s bridge to Europe

Will Lloyd: How Ricky Gervais took on the “woke brigade” and won

Ted Gioia: Is social media a dying mall?

Timothy Aubry: The rise and fall and rise of close reading. Clothes reeling?! What’s that?!

Sarah Skwire: What did Roman emperors do all day?

And with that…

Collective amnesia gripped the Democratic Party after Donald Trump’s triumphant return on 5 November. Many acted as if the past eight years had not happened and clung to the false belief that Trump’s irruption into politics was temporary. Within hours, disbelief turned into a haughty disdain. The risk is that this now calcifies into inaction.

The irony is that are there many opportunities to counter Trump. His pitch as an economic populist which was key in 2016 has been dropped in favour of a vindictive politics reminiscent of Mafia-ruled 1960s New York. And his party is splitting into the techno-libertarians backing Elon Musk and conservative populists coalescing around JD Vance. Expect a power struggle to play out for Trump’s capricious ear.

The anti-trust movement against Big Tech is a way forward for the Democrats. In the hands of the right salesperson, it could be taken out of the law courts and into the political arena, sold as a stirring campaign against tyrannical corporations. But talk of Kamala Harris running in 2028 suggests not all in the party share this analysis.

Political violence has entered this void. Trump suffered two assassination attempts during the campaign. Many liberals have hailed the murder of a private healthcare executive in Manhattan in November as an act of justice – yet another sign that extra-constitutional opposition to the right is becoming normalised. While all three perpetrators appear to have acted alone, America could be entering its own Years of Lead.

In the meantime, Trump will become president at midday on 20 January. What explains his victory?

“We said things that were on the minds of the country,” he has since told Time magazine. “I don’t think [the Democrats] got the feel of the country. The country was angry.” He is right: the Democrats won’t succeed until they figure out how to respond to that anger.

— Freddie

The New Statesman is home to the finest writing on politics, culture and ideas. To stay up to date, subscribe using the link above.