The Saturday Read: Dispatched

Inside: Iran, Truss, O'Hagan, Schumann, a fool, Rushdie II, and live from Trumpland.

Good morning. Welcome to the Saturday Read, the New Statesman’s weekly guide to politics, culture, books, and ideas. This is Harry, along with Jason, Pippa and George.

If you would like to read a dispatch from Trumpland, here’s a short report from the Pennsylvanian suburbs, where the former (and future?) president made various incredible statements at a rally last weekend. At one point he spoke favourably of executing all drug dealers after a one-day trial (“if they're guilty, which they always are…”), a moment that evoked no comment because Trump said it.

Jason starts us off with a reflection on Salman Rushdie, while Nicola Sturgeon, whose husband was also in the news this week, has reviewed Rushdie’s new book for us. And after this week’s picks we’ve spoken to The Atlantic about their recent success.

The author’s blurb on Salman Rushdie’s new book, Knife, styled as “Meditations After an Attempted Murder”, describes him as one of the “world’s most acclaimed, award-winning contemporary authors”. True enough. He is also perhaps the most hunted and most resilient: misunderstood, misinterpreted, misread or not read at all. The man who attacked him on stage at the amphitheatre in Chautauqua in upstate New York in August 2022 said he’d read a “few pages” of his work. He delivered his verdict with a knife.

Rushdie, now 76, has lived under a sentence of death since the fatwa was ordered against him in 1989, in the long, bitter aftermath of the publication of The Satanic Verses. (The street protests against the book and its author began in Bradford, England.) Even today Rushdie remains reviled by some as an anti-Islamic heretic but by others, rightly, as a heroic champion of free speech and the open society. Now he is blind in one eye following the near-fatal attack on him, but no one has taken his voice away: he is still speaking and writing well.

I first spoke to Rushdie in spring 1992. I’d recently joined The Bookseller, a venerable trade journal founded in the Victorian age, my first job in London after leaving university. In one of my early weeks there the editor, Louis Baum, said: “I’d like you to do an interview this morning?”

Who with?

“Salman Rushdie.”

Salman Rushdie!?

“Yes, he will call at an agreed time, and I will put you through.”

Baum was well connected in literary London, I discovered as I got to know him, and his partner, Liz Calder, had edited Rushdie.

This was only three years after the fatwa and Rushdie was in deep hiding – or, as Cynthia Ozick once put it, “wrapped in hiddenness”. He was still published and gossiped about but seldom seen. (We know now that he was living in a mansion on The Bishops Avenue in north London, a billionaires’ road popular with oligarchs and Gulf Arabs.)

I was thrilled to speak to Rushdie whose story and its radiating consequences I’d followed with rapt fascination ever since he went into hiding with a bounty on his head. I met him in person a year or so later when I sat on the same table as him at the Booker Prize dinner; the anonymous man in a tuxedo next to me turned out to be Rushdie’s police protection officer and, as we chatted, he quietly opened his jacket to reveal the handgun he carried.

Rushdie had a reputation back then for extreme arrogance, but I found him courteous and amusing. He was a raconteur but not a tyrannical monologist; I think he spoke a lot about Star Trek that evening, for some reason.

In her piece published today about Rushdie, Nicola Sturgeon, the former first minister of Scotland and an excellent New Statesman book reviewer, calls Knife “therapy, a healing process for Rushdie’s mind”. After all this time, he remains bitter about those writers, politicians and intellectuals who were reluctant to support him publicly after the fatwa. Or who were even openly contemptuous.

He cites John Berger, Germaine Greer, President Jimmy Carter and Roald Dahl as well as various British Tory grandees. He does not mention John le Carré or VS Naipaul, who were both notably dismissive (he was later reconciled with le Carré). When I once mentioned Rushdie to Naipaul, he said: “Why are you asking me about the man who writes like the blind Irishman!” He presumably meant James Joyce.

Sturgeon says that we “we should all reflect on, with some shame” the failure to defend Rushdie and an artist’s right to free expression in an age of creeping censorship and illiberal liberalism (the italics are mine). “In the midst of our modern-day debates about the rights and limits of free speech, we should pay attention to his words,” she writes. I hope they are listening in Scotland as the country is embroiled in a row over the SNP’s authoritarian hate crimes law.

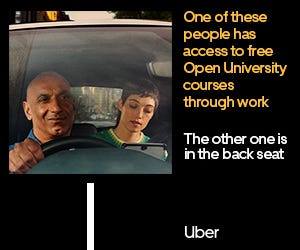

Iran and Israel’s deadly game

Our magazine cover story on the Israel-Iran conflict this week is by Jeremy Bowen, the BBC’s international editor. Bowen writes with terse muscularity and combines on-the-ground reporting with a hard-won understanding of Middle East history – of its factions, religious divisions, and post-imperial torments. “The question is how much room is left for mistakes before the Middle East slides into something infinitely worse,” he asks – by which he means an all-out regional war. (Lawrence Freedman has also written on the conflict for us here.)

1—“Trump wants his crowds to fear, to hate, to act.”

Last Saturday’s Trump rally in Schnecksville, Pennsylvania was the third I’ve attended, after other surreal evenings in 2016 and 2022. Someone I was with captured something I’ve always felt when I go: “There’s an eerie sense that we’re all friends here.” HL

For an hour Trump pummelled his audience, whose attention he does not know how to hold but whose loyalty he has already won. “The [2020] election was rigged, a disgrace… They’re weaponising government, they’re trying to hurt your favourite president… We have to get him [Biden] the hell out of office and send him back to wherever he comes from.”

“The whole world is ablaze,” Trump went on. “Viktor Orbán, a very strong guy, who I think happens to be a very good person, was asked ‘What’s going on with the world?’ And he said, ‘Bring Trump back as president and it’ll all stop!’ Never forget my enemies want to take away my freedom because I will never let them take away your freedom. In the end they’re not after me, they’re after you, and I just happen to be standing in their way.”

2—“He is writing against abject dependency.”

Waterstones, Walkers and Weetabix are US owned. Large American corporations made £2,500 from every UK household in 2019, and two million Brits work for them. And as Will Dunn reminds us in a review of Angus Hanton’s Vassal State: How America Runs Britain, our politicians asked for this. GM

Britain has been singled out for special treatment. The investment made by the US into the UK outweighs its spending in the rest of Europe combined. This is not just because we have a shared language and we were on the same team in the Second World War. Our political leaders have actively courted this takeover. Voters have been told that foreign direct investment, or FDI, is an unequivocal good; it means foreign investors building new factories for grateful British workers.

The reality is that a lot of this “investment” is US private equity firms helping themselves to British companies that are cheaper to buy (thanks to our less buoyant financial markets) than American businesses. This is good for the financial sector, which profits from the boom in buyouts – in 2022-23 alone, US private equity firms bought 181 British businesses – but it means swathes of companies come to be owned by people for whom local employment is not a concern. The UK has lost two million manufacturing jobs since 1991.

3—“This is a big, maximalist, bonkers novel.”

The critic Edward Mendelson defined encyclopaedic novels as those that “attempt to render the full range of knowledge and beliefs of a national culture”. Their audacity alone makes them interesting. Andrew O’Hagan’s Caledonian Road wants to exhaust contemporary London; Anna thinks it successful, if not entirely so. (Anna has also written on the “tortured” Taylor Swift.) GM

Caledonian Road, a book billed as a “headline-grabbing entertainment”, arrives with a TV adaptation (from Chernobyl director Johan Renck) already in the works. O’Hagan and Faber’s publicity team have also branded it a “social novel”, a “state-of-the-nation” novel, even a “reported novel”. O’Hagan has experience here: he has published long-form journalism on subjects including the mysterious founder of Bitcoin, the Grenfell fire and Julian Assange, who he spent hours with while ghost-writing Assange’s memoir.

There is so much going on in this novel – from the unequal impact of the pandemic to organised crime in the art world – and he suggests that corruption is a terminal disease the capital can’t recover from. He has crammed his book with observations of the living, breathing city: O’Hagan has said he walked Deptford streets at two in the morning and visited ritzy Belgravia restaurants on the same day as his characters to make sure every element – architecture, weather, post-Covid regulations – is accurate.

4—“A dishonest, self-serving, self-congratulatory stunt.”

The British TV comedian Joe Lycett, if you haven’t heard, is concerned by fake news. So much so that he’s planting fake stories in the media to promote his new show. Sarah Manavis brings him in for a good drubbing. GM

Lycett has certainly been effective in showing that fake stories can be nefariously planted into the mainstream press and fool journalists. But – if we think about it for more than half a second – what value is there to this gag, really, beyond boosting Lycett’s celebrity and Channel 4’s ratings? It’s not hard to argue that one of the biggest buzzwords of the past ten years – “fake news” – is something the general public cannot detect very well.

But what does Lycett’s stunt teach us? That, uh, fake news… exists? That PRs can write convincing emails that are typically taken in good faith? His moral framing feels confused: is it really a good thing that a set of silly lies made it into the press, rather than the “hateful”, “polarising” stories Lycett tells us normally make headlines? This is a faux-educational, self-righteous prank that shouts about its own importance without saying anything at all.

5—“There is a naive assumption among a certain type of liberal that tolerance is the factory setting of British life.”

The High Court ruled in favour of Michaela Community School – run by “Britain’s strictest head teacher”, Katharine Birbalsingh – after a Muslim student sued it for banning prayer. Twitter detonation of the week goes to Finn McRedmond, who hailed the decision as a win for tolerance. GM

Birbalsingh’s argument is simple: everyone must make sacrifices at the altar of social harmony. Jehovah’s Witnesses, she says, accept studying Macbeth in spite of religious stipulations about texts that contain magic and witchcraft. Christian students attend revision sessions on Sundays. Muslims do not have access to prayer rooms. Every student eats vegetarian food owing to Hindu restrictions on beef and Muslim restrictions on pork.

6—“He frequently suffered excruciating, soul-sapping lows after his creative highs.”

After Bach and Sibelius, Phil Hebblethwaite is on to Schumann. It’s a fascinating tale of a genius raging against the machine. His wife pleaded with him to produce something more palatable, but Schumann could not bear to sanitise his brilliance. GM

For years before Robert Schumann completed his First Symphony in 1841, which he nicknamed the Spring Symphony, he’d been finding that his riotously original solo piano music tended to perplex, even irritate, listeners. Clara Wieck, the greatest female pianist of the age, who became his wife in 1840 after a protracted battle with her disapproving father, would ask him for less nutty pieces that she could play at her recitals, to help draw attention to his obvious raw talent as a composer.

But, as he once said to a critic who reproached him for not writing piano sonatas that obeyed traditional structural rules: “As if all mental pictures must be shaped to fit one or two forms! As if each idea did not come into existence with its form ready-made! As if each work of art had not its own meaning and consequently its own form!”

Five minutes with… Nick Thompson, CEO of The Atlantic

The Atlantic is one of two American magazines in the midst of a golden era right now. (New York Magazine is the other.) We will have more in the NS soon on the degree to which the major British news publishers – The Times, Guardian, Telegraph, FT and Economist – are prospering as the digital era develops; their numbers may surprise you.

This week we spoke briefly to Nicholas Thompson, The Atlantic’s CEO, and former editor-in-chief of Wired, about how the magazine has turned itself around in the past three years, reaching profitability, passing 1 million subscriptions, and winning the US magazine industry’s General Excellence award for the third year in a row. HL

What have you found to be the main reasons why people subscribe?

Many factors come together: brand association, writer association, support of the mission. But to choose one sentence and one reason, I would say: “to read stories at specific moments that people are talking about.” It’s very story-specific.

Writing big pieces that people feel the need to read remains the game. But what has surprised you in the past few years?

We started running lots of tests – on the placement of our paywall, on our pricing point – and it turned out that a tighter paywall actually worked. I had assumed that you need a looser wall, but most of the experiments we ran led us to a more restrictive one.

How much is journalism now a star-led business? How much are you kept awake at night wondering if Caitlin Flanagan, Tim Alberta, or Jennifer Senior might leave?

I think having a roster of writers that people associate with your title is absolutely essential. But I don’t think that’s changed in the past two years, I just think we’ve made The Atlantic a good place for the best people to work.

But do you have good data on who brings in subscribers?

I have all the data, but I’ve never looked at it. No one looks at it. We are much more general in how we think about strategy. I also don’t weigh in on who we should hire as writers, that’s Jeff’s domain [Jeff Goldberg, The Atlantic’s editor].

How much of a threat is Substack to lure away the top 1 per cent of your talent?

There was a period where I thought Substack was the number one threat to take writers but that moment was passed. It seemed like everyone could make tons of money from writing their own newsletter but now it’s clear that only some people can. We also put more effort into our own newsletters, which gave writers who were seeking that an outlet. We are focusing on areas where we control the relationship with the reader.

How do you think about traffic at this point?

One of the shocking things about our subscription success is that we’ve done it with so much less traffic, because of the changes to social. We’d be doing way better if we’d built all these models back when we had lots of traffic.

We work as hard as we can to get as much traffic as we can from the social platforms, whether it’s from X, Instagram, or Google Discover. But if you look at the amount of traffic we used to get from, say, Facebook, it’s been a catastrophic decline. There were tons of people who would have found The Atlantic through the old Facebook algorithm who would ultimately have subscribed, who do not find it anymore. I sure wish we had that back.

How do we protect the upsides of flexibility for workers whilst providing security and union representation? What is the right balance between workers’ autonomy and worker protections? Listen here to our exclusive podcast episode, in partnership with Uber as they approach the three-year anniversary of their recognition agreement with GMB Union, where we discuss the future of work in 21st-century Britain.

George’s Best of the Rest

Telegraph: Majority of Gaza’s IVF embryos destroyed by Israeli strike.

FT: US aid to Ukraine on verge of being passed by House after long delay.

Sky: Nicola Sturgeon’s husband, Peter Murrell, charged in connection with embezzlement.

Christopher Gage: On the great British smoking ban.

George Parker: Lunch with Liz Truss. I leave the withering asides to you.

Ross Barkan: The parasocialism era.

John Hendrickson: RFK Jr’s strategy clicks into focus.

Kyle Chayka: On the internet’s new favourite philosopher. A dubious honour.

Northern lights shine over Iceland’s erupting volcano. Save some spectacular nature for the rest of us, Iceland!

Endangered Bornean orang-utan born in Florida, weighing 3lb.

If today’s pieces intrigued, you can subscribe to the New Statesman below. Stay up to date with everything from news and analysis to comment, criticism and essays.

Whether you’re looking for a sharp blog or a finely written feature, the New Statesman has you covered. Have a good week, and catch you next Saturday.