The Saturday Read: Distorting mirror

Inside: Glazer, Ramallah, TBI, tech, Butler, Tavistock, Oyler, Kate, and rural wrath.

Good morning. Welcome to the Saturday Read, the New Statesman’s weekly guide to politics, culture, books, and ideas. This is Harry, along with Pippa, George Monaghan, and Will Dunn.

This week we interviewed Thomas Piketty, perhaps the most consequential economist of the 21st century (it’s early yet). You may enjoy the conversation. We highlighted the piece in Morning Call, our political newsletter, to which it is now possible to subscribe and receive a daily recommended piece in full in-email, among other delights. A year’s subscription is £3 a month.

A gangster called “Barbecue” is said to have taken over Haiti, a state in collapse. Don’t miss this NS report by Pooja Bhatia from last May on the country’s descent into hell. And John Berger has signed us off this week, from 1954.

1—“Why would Glazer, of all people, give the slightest weight to this libel?”

Jonathan Glazer won a richly deserved Oscar (Best International Feature) for The Zone of Interest last Sunday. He then delivered “an apology for his Jewishness so grovelling in its emotional simplicity it would have made the angels – of any religion – weep”, writes Howard Jacobson. “Right now, we stand here,” Glazer said on stage, “as men who refute their Jewishness and the Holocaust being hijacked by an occupation which has led to conflict for so many innocent people.” What did he mean by that? HL

There is disagreement about the meaning of this clumsy formulation. Is Glazer refuting his Jewishness full stop, or refuting his Jewishness being hijacked to justify an occupation? Because I want to give him every benefit of every doubt I will accept the latter explanation. So that’s all right then. He’s holding on to his Jewishness after all. Whew!

Except that it’s not all right. What and where is this hijacking of which he wants no part? I have not myself heard any serious, thinking moral Jew adducing the “occupation” to the Holocaust, though I have heard it said by those for whom discrediting Jews is a passion that this is the sort of moral blackmail Jews routinely employ. Jews, it is said, cry anti-Semitism only to silence criticism of Israel, just as they help emergency relief efforts in other countries only to harvest the organs of the dying, just as they selectively murder children because that’s what they’ve been doing for centuries…

2—“The West Bank is at boiling point.”

Megan Gibson reports from Ramallah, where Israeli security forces have been extending their presence in the occupied West Bank, and illegal Israeli settlements are being built under the cover of the war in Gaza. Will sectarian tensions ignite? Settler violence – torching cars and houses, beating and driving Palestinians out of their homes at gunpoint – is rife. PB

Khalil Shikaki is one of the leading scholars on Palestinian state-building and public opinion. He has conducted more than 200 polls among Palestinians in Gaza and the West Bank over the past 30 years. When he describes the West Bank as “boiling”, one should take notice… As the Israel Defense Forces prepare to launch a ground incursion into Rafah, where as many as 1.4 million displaced people are gathered along the Egyptian border in Gaza, there are fears that Palestinians are reaching a breaking point. As Shikaki put it, “Since the end of the Second Intifada, the West Bank has never seen the kind of destruction, the kind of violence that we see now.”

3—“Sectarianism has returned to England.”

Jonathan Rutherford takes the temperature of sectarian hostility in these Isles, and finds it far too high. A Labour government, he cautions, will not survive one term without a thoughtful response to this new danger. He also captures something deeper about how power now works across many powerful organs of British society. HL

Part of the ruling class but subordinate to the economic elite, [the] power [of this professional class] lies in its control of communication, language and valuable cultures. Its administrative method of change circumvents democracy through its control of NGOs, and institutions of learning and culture. While it attacks the inequalities of the old bourgeois society it advances its own inegalitarian class privilege as judge and regulator of the normative structures of society. Higher-educated, liberal, and majoritively white it allies with the interests of oppressed groups in order to sustain its own status and power.

4—“In very crude terms, the TBI people are fascinated by the possibilities of using tech.”

The New Statesman’s polling model predicts a 182-seat majority for Labour if an election was held tomorrow. With the growing likelihood of a Labour government comes a growing battle over who will secure its priorities. Andrew Marr reports on the struggle at the heart of the next government. WD

The previously neat division in Starmer’s office between those tasked with winning the election – led by Morgan McSweeney, Labour’s campaign director – and those thinking principally about life after a victory – led by Gray, Starmer’s chief of staff – is proving increasingly unsustainable. The manifesto must be both a weapon to win votes and a guide to life after the election: “Nothing would be worse at a time of low public faith in politics than winning and then changing direction,” says someone close to Starmer.

5—“How do we consume as much of your time and conscious attention as possible?”

True happiness, according to Epicurus, was not found in indulgence or excess but in the state of ataraxia – the untroubled mind, the freedom to focus and think with clarity. Ed Smith remembers being taught this principle at 18, when a cricket coach told him what makes great players distinct is that they are capable of “the absence of irrelevant thought”.

The smartphone is a machine for introducing it as often as possible. The business model that underpins it is that human attention must be broken, again and again. Silicon Valley has conducted a 15-year, unregulated experiment on the brains of most of the world’s children; Jonathan Haidt, author of The Coddling of the American Mind, wants to call time on it. WD

Haidt cites Kurt Vonnegut’s 1961 short story “Harrison Bergeron”, which envisages an American dystopia in which being excellent at anything (and therefore un-egalitarian) has been made illegal. The preferred weapon of “handicapping” exceptionally bright people is to make them wear an earpiece which buzzes roughly every 20 seconds to sabotage sustained concentration. Stopping attention is the lever by which intelligence can be flattened.

Virtual reality platforms like Rezzil are helping athletes like Marcus Rashford return to the game with confidence. Find out more

6—“Is ‘gender theory’ totalitarian or are its opponents?”

“Judith Butler’s hip quietism is a comprehensible response to the difficulty of realising justice in America. But it is a bad response. It collaborates with evil. Feminism demands more and women deserve better,” wrote Martha Nussbaum in 1999 in a famous essay on Butler I linked to last week. (“The Professor of Parody”).

That essay is worth reading before diving into any other piece on Butler, such as this review by Lyndsey Stonebridge of her new book. For Stonebridge, those who disagree with Butler’s position on gender – that it is a social artifice – are driven by “moralism, certainly, but with a sadistic charge”. Some readers may find that reductive. HL

The arrival of gender theory into university classrooms did not herald a new progressive dawn. In the UK, memories of Section 28 – the legislation banning the “promotion of homosexuality” in schools – regular attacks on abortion rights and the always present hum of misogyny and homophobia made sure of that. Still, there was a loosening and a sense of possibilities opening up. Straight boys would try to get into the London gay nightclub Heaven by wearing eyeliner and tagging along with their queer friends.

Nobody then, and certainly not, I imagine, Judith Butler, could have imagined today’s gender wars. In our joyless, ungenerous, unironic times, gender theory has become an ideological and at times literal battlefield.

7—“It is possible puberty blockers will never be available again on the NHS.”

NHS England this week confirmed that puberty blockers will no longer be prescribed on the NHS. The polarising decision is, writes Hannah Barnes, “based on evidence”. It means there will be no medical pathway for those presenting at the new gender services that are due to replace the Tavistock on 1 April. PB

The thorny issue of private providers prescribing puberty blockers remains unaddressed by the announcement. NHS England says it fell outside the scope of its consultation. However, it said that it did not know of any regulated source of blockers outside the NHS and could not support anyone sourcing of them privately because of a lack of sufficient evidence over the “safety and clinical effectiveness” of the drugs.

8—“The technique gives her essays a titillating immediacy.”

Lauren Oyler – whose “preoccupations could not be more Small Circulation Lit Mag, spring 2024, if they tried”, as Rachel Cooke recently put it – is famous for being mean. But is she? Lola Seaton examines her new essay collection. Oyler obsessively builds defences, then obsessively highlights, thereby undermining, those same defences, producing a thrilling ambiguity. “Oyler’s overt self-awareness,” Lola proposes, “makes us self-aware”. GM

She cut her teeth writing for Vice and her career has been distinguished by “lily-pads of semi-viral critical articles”. A self-described internet addict with a sizeable Twitter/X following, Oyler is fearsomely fluent in digital culture, especially the idioms and humour of social media. She knows how to sound interesting online and this has left its mark on her style. Her prose has the taut, incessant wit of repartee, as though each sentence had to be worthy of a tweet.

9—“You are not supposed to question its reality.”

Our national psyche is never more eccentric than in our treatment of the royals. This week, as Will Lloyd recounts, we were consumed by the eerie edits made, allegedly if implausibly, by Kate Middleton to a photo of her and her children. “This is what happens when the most photographed woman in the world stops being photographed.” GM

That it has taken a manipulated photo to put dents in that machine is telling. The British generally want to believe in their royals. (You do not visit the zoo to question the veracity of the zebra’s stripes.) This unforced error, at a time when all institutions lack credibility and the King is seriously ill, has broken the story the Windsors tell their people. Late on Monday 11 March, another photo appeared. Prince William, accompanied by a cloudy grey smudge in the back of an official car. The smudge was supposed to be his wife. In a strange way it felt like we were seeing Catherine properly for the first time.

10—“All this is a dim memory in today’s Democratic Party.”

When the Democratic Party was founded in the late 1820s, it threatened to smash the “moneyed aristocracy” and to empower small-time farmers and urban workers. Today, many supposedly progressive commentators are scornful and dismissive when addressing the back country. But if Joe Biden cannot win back more of rural America, November’s election may be lost, writes Sohrab Ahmari. PB

Consider the Washington book du jour, White Rural Rage: The Threat to American Democracy, by the political scientist Tom Schaller and the journalist Paul Waldman. The “threat” in the subtitle concerns the outsized influence rural whites supposedly wield over the political process. This, even though they also harbour “undemocratic, sometimes violent impulses”, according to Schaller and Waldman. Rural folk are, they say, bigoted, conspiratorial, anti-democratic – just appalling.

11—“Mr Tinker has been unreasonably persistent.”

At least ten of the estimated 67,000 people to have been affected by the loan charge – a retroactive tax demand by HMRC – have taken their own lives. Many more have faced bankruptcy, family breakdown, the loss of their jobs. Our investigation finds that they thought that they were paying tax when they used “payroll loan” schemes, and were given little reason to worry by HMRC, which was aware of how they operated. Gary Tinker was one of those people, but he’s not just fighting his own case. WD

On the messaging channels used by people affected, he has seen the panic and misery that the loan charge has caused, again and again: people suffering in silence because they don’t want to tell their families, people whose marriages have been broken by the sudden collapse of their finances. The suicides, while they are the most disturbing result of the policy are “the tip of the iceberg”, he told me.

George’s Best of the Rest

Variety: Oppenheimer sweeps Oscars. It blew away the competition.

Barron’s: Saudi king calls for end to “heinous” Gaza crimes in Ramadan message.

AP: Biden-Trump II: officially the first presidential rematch since 1956. No Googling it now!

WSJ: As the US TikTok crackdown intensifies, a forced sale looks likely.

Jonathan Haidt: End the phone-based childhood now.

Spencer Klavan: The Ick. He’s a ten but he’s not subscribed to the Saturday Read.

Oliver Bateman: The Rock is a harbinger of America’s decline.

Freya India: You can’t buy an authentic self.

Declan Ryan: Getting messianic with Seamus Heaney. And what venerable outlet first published Digging?

David Schaengold: A world nobody wants.

UK middle-aged cancer deaths fall by a third over the past 25 years.

Britain to catch American tree-height record in 590 years. That means we win.

Elsewhere on the NS

Was the social media response to the Amber Heard trial a coordinated campaign of hate? A new podcast doesn’t quite find the answer, writes Anna Leszkiewicz.

An anonymous polyamorist warns of free love’s perils.

Gus O’Donnell, the former cabinet secretary, is quite Pollyannaish about Rachel Reeves, Keir Starmer and Labour in this interview with George Eaton. He’s not keen on Brexit, though: “We haven’t been able to offset the obvious fact of tearing up one of the best trade deals we ever had with our largest trading partner.”

Did Capital in the Twenty-First Century, Thomas Piketty’s landmark study of inequality, change anything? Quinn Slobodian investigates. “For now, the target demographic for books on inequality remains what Piketty scathingly identified as the ‘Brahmin left’ – highly educated people willing to consume critiques of the system while remaining too materially committed to risk its transformation.”

Sarah Manavis explains the return of the easy, hashtag-friendly feminism of the early 2010s.

Ellen Peirson-Hagger meets Suzie Miller, the former lawyer whose play about sexual assault, Prima Facie, changed the law – and won Jodie Comer a Tony.

Jonny Ball finds Andy Burnham and Steve Rotheram’s new book about the north of England suspiciously laddish.

Katrine Kielos-Marçal argues that if you fear AI, you really fear yourself.

Richard Beard discusses the revelations of private school sex abuse in Charles Spencer’s new memoir, concluding that “scrutiny is timely and necessary”.

And with that… John Berger: Why Picasso? (1954)

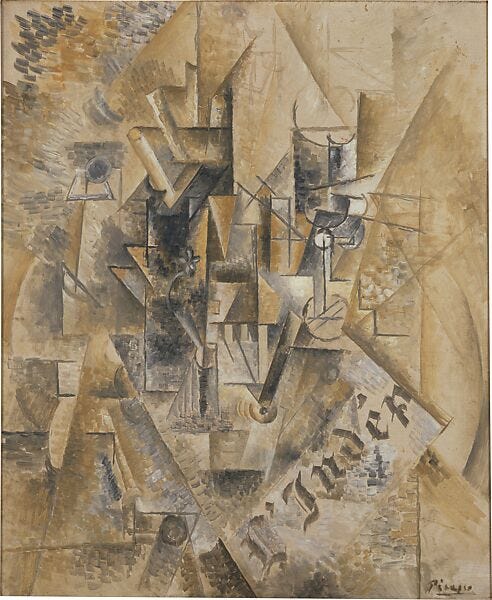

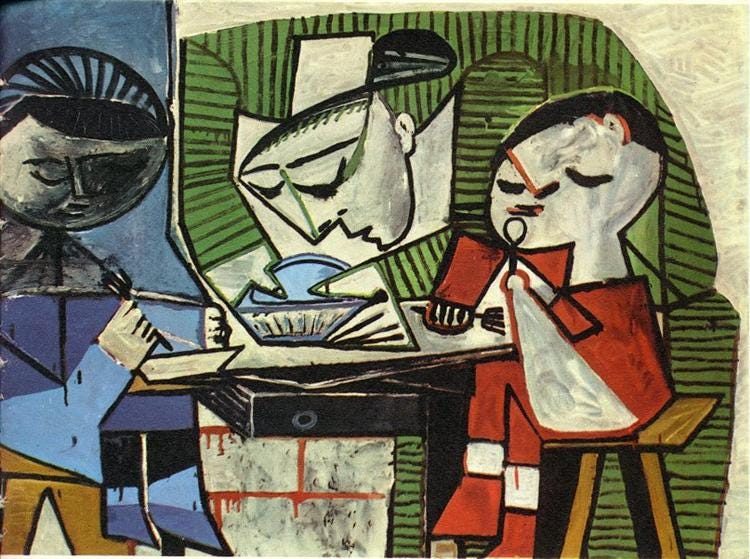

Why is Picasso the most famous living artist in the world? Why does everything he does have such news value? Why do even those of us who are more seriously interested than the sensational press, go to a new Picasso exhibition hoping to be surprised? And why do we never come away disappointed?

Take the present Picasso show at the Lefèvre. It contains two jokes cast in bronze. One is an ape with a toy model car for a head, a vase for a belly and a piece of an iron bracket for a tail. The other is a bird with a head and plume made from a gas-tap, a tail from the blade of a small shovel and legs and feet from two kitchen forks. The fifteen paintings include some recent sketches of women’s heads in which profile and full-face are dislocated and re-assembled together, a flippant canvas of a dog and a woman wrestling hammer and tongs on the floor, and two small pictures from the tragic series of women in hats painted during the German occupation – their faces brutally wrenched into shapes reminiscent of gas masks. There are no important works in the show. Yet it remains intensely memorable. Why?

The easy answer is to say: because Picasso is a great artist – because he can set a model car in clay and somehow make it convincing as a head of an ape – because he can draw a goat’s skull (No. 20) with such finesse that one can feel every twist and turn worn away by the muscles. But to answer like that is to beg the question. It doesn't explain why the scrappiest work by Picasso is so disproportionately compelling, or why all his work is so much more immediately arresting than that of, say Matisse or Léger who in the long run will probably be seen to possess equal or even greater genius as painters.

Those who petulantly and sceptically say ‘You only admire it because it’s been done by Picasso’, are in a way quite right. In front of Picasso’s work one pays tribute above all to his personal spirit. The old argument about his political opinions on one hand and his art on the other is quite false. As Picasso himself admits, he has, as an artist, discovered nothing. What makes him great are not his individual works but his existence, his personality. That may sound obscure and perverse, but less so, I think, if one inquires further into the nature of his personality.

Picasso is essentially an improviser. And if the word improvisation conjures up amongst other things, associations of the clown and the mimic – they also apply. Living through a period of colossal confusion in which so many values both human and cultural have disintegrated, Picasso has seized upon the bits, the fragments, the smithereens, and with magnificent defiance and vitality made something of them to amuse us, shock us, but primarily to demonstrate to us by the example of his spirit that within the confusion, out of the debris, new ideas, new values, new ways of looking at the world can and will develop.

His achievement is not that he himself has developed these things, but that he has always been irrepressible, has never been at a loss. The romanticism of Toulouse Lautrec, the classicism of Ingres, the crude energy of Negro sculpture, the searchings of Cézanne towards the truth about structure, the exposures of Freud – all these he has recognised, welcomed, pushed to bizarre conclusions, improvised on, sung through, in order to make us recognise our contemporary environment, in order (and here his role is very much like that of a clown) to make us recognise ourselves in the parody of a distorting mirror.

In Guernica the parody was tragic; there, angrily and passionately, he improvised with the bits left over from a massacre: as in other paintings, also tragically, he improvises with features and limbs dislocated and made fragmentary by the dilemmas of our time. But the process, the way he works – not by sustained creative research but by picking up whatever is in front of him and turning it to account, the account of human ingenuity – is always the same. Even when as now he makes a bird from the scrap metal found in some cupboard.

Obviously this shorthand view of Picasso oversimplifes, but it does, I think, answer the questions I began by asking. And also goes some way to explaining other facts about him: the element of caricature in all his work; the extraordinary confidence behind every mark he makes – it is the confidence of the born performer; the failure of all his disciples – if he were a profoundly constructive artist this would not be so; the amazing multiplicity of his styles; the sense that, by comparison with any other great artist, any single work by Picasso seems unfinished…

The conclusions one can draw are these: that it is Picasso’s simple and incredible vitality that is his secret – and here it is significant that of all his works it is those that deal with animals that are most complete and profound in sympathy; that to future generations our estimate of Picasso, judged on the evidence of his works themselves, will seem exaggerated; and that we are absolutely right to hold this exaggerated view because it is the present existence of this spirit that we celebrate.

First published in the New Statesman, 1954.

If today’s pieces intrigued, you can subscribe to the New Statesman below. Stay up to date with everything from news and analysis to comment, criticism and essays.

Whether you’re looking for a sharp blog or a finely written feature, the New Statesman has you covered. Have a good week, and catch you next Saturday.

Re Glazer

This is a hopeless piece of coverage and I’m surprised. It is amazing how such a clear and brave statement has been so widely misinterpreted… he was clearly refuting the hijacking of his Jewishness by the occupation which is killing so many people in Israel and Gaza… that ‘s clearly a reference to the current aggressive, genocidal and apartheid tendencies which tragically characterise the current identity of Israel . In fact as Naomi Klein I think sez in the guardian today, his film is about people who continue to pursue their best life in spite of the terror and destruction that is being carried out in their name all around them. Please read this article in the London review of books and find some serious historical analysis of the hijacking of which Glazer speaks. https://www.lrb.co.uk/the-paper/v46/n06/pankaj-mishra/the-shoah-after-gaza

The New Statesman is fabulous ... always has been ... I have been a fan for the past 51 years that I have been a foreign correspondent (NYTimes, CBS, and beyond) ... now CNN columnist but especially SubStack's Andelman Unleashed ! You folks should (also) subscribe (free) to me! e.g.: https://daandelman.substack.com/