The Saturday Read: Double-edged

Inside: Keir, the exiled right, cool girl novelists, IQ, the police, and capitalism itself.

Good morning, and welcome to the Saturday Read, the New Statesman’s weekly guide to the best writing on ideas, politics, books and culture. This is Will, along with Pippa and Harry.

I have been living like a hermit – or “catching a marlin” as Harry put it last time – for several weeks now as I put together quite a long, involved piece. It should be out relatively soon. In the meantime, here’s a hint for you.

If today’s pieces intrigue, perhaps you’d like to try a trial subscription to the NS. Read three free articles after registering on our site. A digital subscription is only 95p a week. Let’s get to it.

“Observing molecules in VR helps me understand them better than ever.”

1—“Labour must persuade voters not simply that the last 14 years have been a failure but that real change is possible.”

Our political editor, Andrew Marr, opens up the thinking going on inside Keir Starmer’s head right now. Who is the next prime minister? The Labour leader looks almost certain to win next year’s election – just don’t call him, or anyone in the leader of the opposition’s office, an optimist. WL

Personally, he is a principled and moral man. Add in his dislike of politics as a game; his preference for flying solo, rather than as part of a political club; and a powerful streak of hyper-competitiveness. Add, finally, his absolute refusal to use his own family for political advantage, and that he came late to politics… and the confusion about him is hardly surprising.

I think he would make a far better prime minister than a party leader. People who work closely with him say that his most powerful quality is his temperament. He doesn’t agonise about personal slights or hostile newspaper coverage. They say that compared to other political leaders he has remarkably little ego; that he is ready to give others the credit, and is calm about his personal status.

Perhaps you might like to sign up to our weekday political newsletter:

2—“In Westminster there are whispers that would have been unthinkable a year ago: Liz Truss was right.”

Just over a year ago, Liz Truss entered 10 Downing Street and cut the ribbon on one of the worst governments in modern British history. At least, that’s the conventional view. Rachel Cunliffe has interviewed many of the key players in Trussworld and discovered that some are less unhappy with what happened in 2022 than you might think. WL

Those who worked closely with Truss add (with varying degrees of tact) that the former prime minister bears some responsibility. “Things unravelled very quickly,” Kwasi Kwarteng told me, when reflecting on those frenetic weeks. He believes the “fundamental error” he and Truss made was the announcement of tax cuts alongside a £130bn energy support scheme without any accompanying savings. “I don’t think there was much strategy. She wanted to do things very, very fast. I look back, and even at the time I thought we were going very, very fast. I remember saying after the mini-Budget, ‘We need to calm things down.’ And she said, ‘I’ve only got two years.’ I said, ‘You’ll have two months if you carry on like this.’ She was just going to blow up.”

3—“In angsty novels by cool girl novelists it is the student condition, not the human condition, which is rendered.”

Charlotte Stroud examines the phenomenon of the “cool girl novelist” – or should it be “sad girl novelist”? They have become one and the same, she argues. A generation of Very Online millennial authors has taken to writing in a common tone: clipped, downbeat and adolescent. HL

The silly novelist has no desire to entertain, she wants to do something far worthier: to impress us. It is for this reason that the cool girl novel is glutted with irrelevant references to artworks and philosophical texts, sewn in like badges on a Brownie sash to display the accomplishments of the writer. It is for this same reason that we are often presented with etymologies or paragraphs on the mating patterns of molluscs. Like the student in a class, their arm stretched so high it begins to quiver, all these novelists want is for someone to say: “Well done! Top marks! Haven’t you read a lot!”

These writers, however, also know that it’s deeply uncool to be so eager, which is why they carefully mask it with a veil of teenage angst. If Jean-Paul Sartre gave us the original novel of existential angst, the adult version, then these books are written by his decadent great-grandchildren. The exiled artist, once a revolutionary figure, has become a brand. To be an exile, these writers believe, is not only a guarantee of your artistic sensibility, but of your social status. Alienation is cool. Our (anti) heroines are never at home – not in their bodies, not in their houses and not with other people. It would, after all, be a sign of unexamined conservatism to be anything other than deeply unhappy under capitalism.

4—“But what’s that, coming over the hill? Surely not – crimes!”

Richard Osman is, by the metric of sales alone, the country’s most popular novelist. Reading his bland visions of Britain, Anna Leszkiewicz wonders why. PB

“If Richard Curtis defined his Britain as ‘the country of Shakespeare, Churchill, the Beatles, Sean Connery, Harry Potter and David Beckham’s right foot’, then Osman’s is the country of Morse, Marks & Spencer, Escape to the Country, Holland & Barrett, Carpetright, talkSPORT, Celebrity Antiques Road Trip, Pizza Express, Rogue Traders, Robert Dyas and gins in tins. (This is the brand-name school of scene-setting.) Violence is localised and interpersonal – motivated by individual greed or petty revenge. Murderers buy their knives from John Lewis and fist fights break out over the Call the Midwife Christmas special. It is a portrait that is neither utopian nor satirical, but hangs limply in-between, existing to provoke a mild chuckle of recognition from middle-class readers.”

How to make IT sustainable

The IT industry has been a significant source of environmental damage, but is now transforming itself. It has responded to the need to develop better sustainable IT, from manufacturing to services to decommissioning. In partnership with Intel vPro.

5—“The return of IQ fetishism did not happen spontaneously.”

In this week’s magazine, Quinn Slobodian traces the revival of a toxic ideology – IQ elitism – and how it has become the creed of the new tech right. The essay is deftly bookended by Michael Young’s The Rise of the Meritocracy, 1870-2033. HL

In the run-up to Donald Trump’s election in 2016, the intelligence question emerged again in the ecosystem of what was now being called the alt-right. Charles Murray’s work on the supposed “forbidden knowledge” of intelligence research resurfaced for another round of controversies, claims and counterclaims, as the “intellectual dark web” earned excited profiles in the New York Times. Trump seemed fixated on IQ, referring frequently to his own apparently high score. The tone was captured well in a tweet from 2013 that read: “Sorry losers and haters, but my IQ is one of the highest – and you all know it! Please don’t feel so stupid or insecure, it’s not your fault.”

6—“If I see police officers coming towards me, I cross the road.”

Following a series of high-profile scandals, reports and gross failures, public trust in the police has more than halved in a year. Anoosh Chakelian asks: is the force beyond saving? PB

“When did policing in Britain become so broken, and who is to blame? In recent months, the New Statesman has spoken to dozens of people close to the front line, including serving and former officers, police chiefs, politicians and criminologists. They disagreed on much but concurred on one thing: that neither a change in leadership, nor a culling of the ranks – a mass “bad apple” composting – would solve its problems. Instead, they argued for something more radical: a complete reimagining of how we are policed, and of what the police are for.”

7—“The parallels between the two dictators are striking. Both articulated projects that are both colonial and decolonising.”

Brendan Simms on what Putin learned from Hitler: the Cambridge historian identifies common elements in the two autocrats’ world-views, and exposes their deranged language of oppression. HL

Again and again, Hitler referred to the Germans as “slaves” who lived on “plantations” in a colony run by allied “overseers”. Germany itself he described as nothing more than a “n****r state”. This was because the country had been beaten, (partly) occupied and subjected to a punitive reparations regime that threatened its national assets, such as the railways, and the very health of its people, who had already been weakened by the wartime blockade. Hitler explicitly compared Germany’s fate to that of areas colonised by the British in Africa, Asia and especially North America. After all, the Führer argued, the American continent had not been presented to the “white man” by a “host of angels”, but instead forcibly taken from the “redskins” with “powder, shot and brandy”. He dismissed international law in the form of the League of Nations as a mere instrument of the Allies.

8—“That’s Tronti. Double-edged, double-tongued. Paradoxical. Ironic.”

Another splendid essay from Madoc Cairns, on Mario Tronti, the radical Italian left-wing theorist. WL

So here we are: depoliticised societies, disorientated peoples: wasteland around us; deserts within. We’re trapped behind the bars of an eternal present, Tronti writes. We’re trapped inside ourselves. When people say capitalism reflects human nature – selfish, spiteful, unfeeling – they’re right. Capital remade us that way. This world can’t be accepted, Tronti writes. But neither can it be changed. How do you say no to a boss who lives inside your head?

Will’s Best of the Rest

Politico: The Silicon Valley doomers behind Sunak’s AI pivot.

Guardian: Monarchy “allowed to censor” coronation coverage. First Diana and now this!

FT: Labour cannot fix UK through tax and spend, says Tony Blair. Britain’s last Thatcher fan speaks out.

AP: Sweden brings back paper books and handwriting in schools.

Times: China’s spy at the heart of Westminster was a private-school boy. Anybody ever beat this guy up in a dorm room?

McKay Coppins: What Mitt Romney saw in the Senate.

Gaby Del Valle: The tradwife burlesque.

Taylor Lorenz: The woman who invented being an influencer. She has quite a lot to answer for!

Christopher Caldwell: The fateful 1990s.

Sophie Vershbow: How publishing became addicted to blurbs.

“I’m basically a human selfie stick.” Meet some very sad men.

Let children do whatever mad thing they want to do, say British.

No one’s talking online any more. No comment.

Elsewhere on the NS

The Pax Americana is over, and it’s not coming back, argues Michael Lind.

Katie Stallard writes about the world’s ugliest couple.

“Leaving nothing to the imagination, the lotus – the symbol of India’s ruling party – was chosen as the logo of the Delhi summit.” Shruti Kapila looks back at last week’s G20, and how it heralded Narendra Modi’s bid for a new world order.

“Gurner’s remarks have been ‘ratioed’ online, as the kids say. Yet he deserves gratitude for venting the id of neoliberal capitalism, giving voice to the fundamental assumptions that have guided economies across the developed world for the better part of two generations.” Sohrab Ahmari on the viral video of the week.

Pippa Bailey on life without a mobile phone. (Spoiler: it’s not easy.)

Ezra Collective may have won the Mercury Prize, but Britain is still scared of jazz, writes Kate Mossman.

David Sexton reviews A Haunting in Venice, an Agatha Christie that isn’t really an Agatha Christie at all.

Chris Patten has some advice for the government: stop being so nice to China.

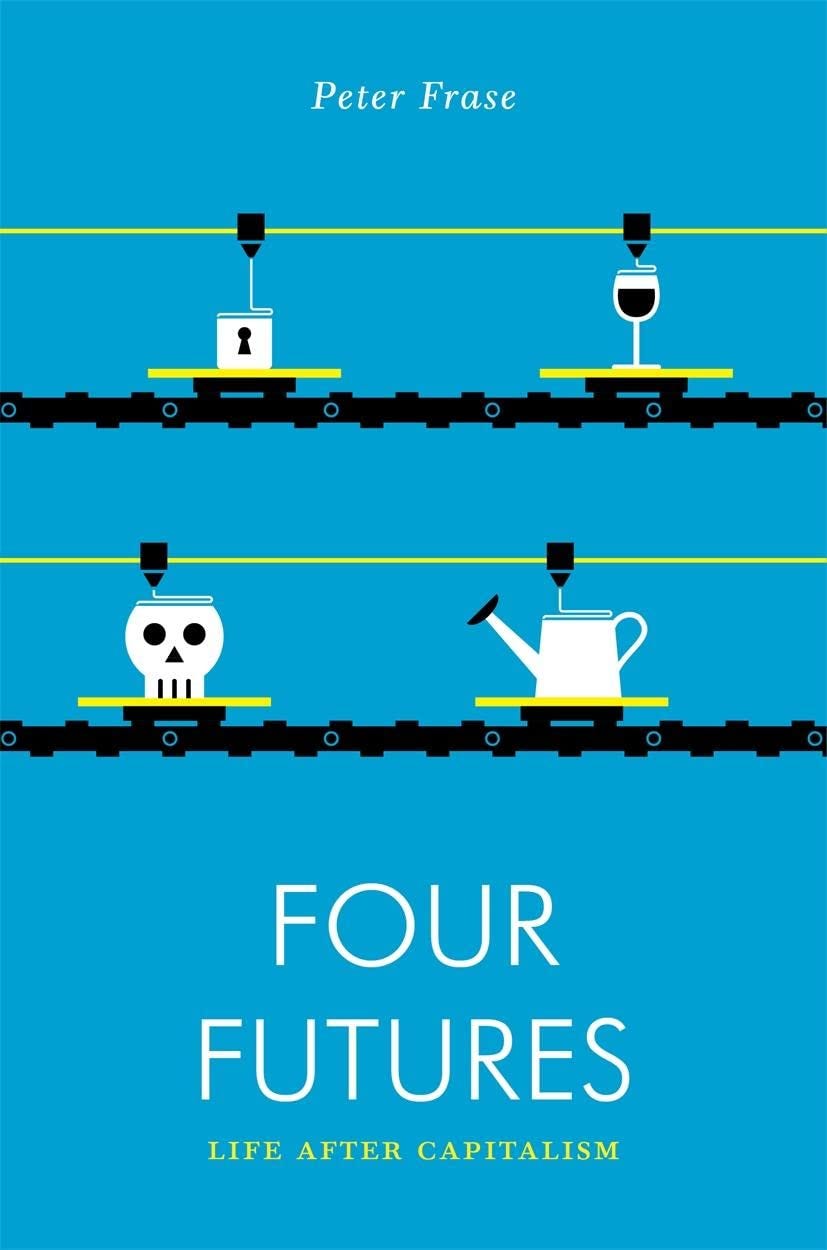

How to get into: Capitalism

Each week we ask someone to recommend three books as a way into a subject. This week we turned to George Eaton, our senior editor, who has picked three intriguing books on capitalism.

Dancing with Dogma: Britain Under Thatcherism by Ian Gilmour (1992): The finest critique of Thatcherism was written not by a liberal or a socialist but by that now rare species: a One Nation Conservative. Gilmour, who served for two years at the Foreign Office in Thatcher’s government, dismantles her economic policies with mordant wit. Of Britain’s privatisation mania, he writes: “If the left had ever perpetrated a similar confiscation on the rich, the right would have howled with righteous rage and pain.”

Too Big to Fail: Inside the Battle to Save Wall Street by Andrew Ross Sorkin (2009): Fifteen years on from the financial crisis, its aftershocks continue to shape the world. Too Big to Fail is an astonishingly rich portrait of the players and institutions who were at its heart: Dick Fuld, Jamie Dimon, Lloyd Blankfein, Hank Paulson. Such is the intricacy and depth of Sorkin’s reporting that reading his book resembles an out-of-body experience.

Four Futures: Life After Capitalism by Peter Frase (2016): This work of “social science fiction” by a Jacobin editor explores four possible scenarios for life after capitalism: luxury communism (equality and abundance), rentism (hierarchy and abundance), socialism (equality and scarcity) and exterminism (hierarchy and scarcity). Of these four, it is the last that lingers longest in the mind. Frase makes the haunting observation that “the great danger posed by the automation of production… is that it makes the great mass of people superfluous from the standpoint of the ruling elite”.

Thank you for reading. Don’t miss out – subscribe to the New Statesman and stay up to date with everything you need: from news and analysis to comment and criticism.

Whether you’re looking for a sharp blog or a finely written feature, the New Statesman has you covered. Have a good week, and catch you next Saturday.

Thanks to Chris Bourn and Pippa Bailey.

Another fine haul.

Charlotte Stroud: what to make of this strange Mansplainesque critique of contemporary women writers? Rachel Cusk reduced to ‘original cool girl writer’

With the suggested cure to all this lamentable cool girl ire, being more Clive James worthy quippage ...

WowFace