Good morning, and welcome to the Saturday Read, the New Statesman’s weekly guide to the best writing on ideas, politics, books and culture. This is Harry, along with Will.

On Wednesday we sent you the first Saturday Read Conversation, a new series of periodic Q&As with leading writers and thinkers. We spoke to Helen Lewis, deputy editor of the New Statesman from 2010 to 2018 and now a staff writer at the Atlantic. If you didn’t catch it, you can read it here. And you can subscribe here to Helen’s weekly Friday email:

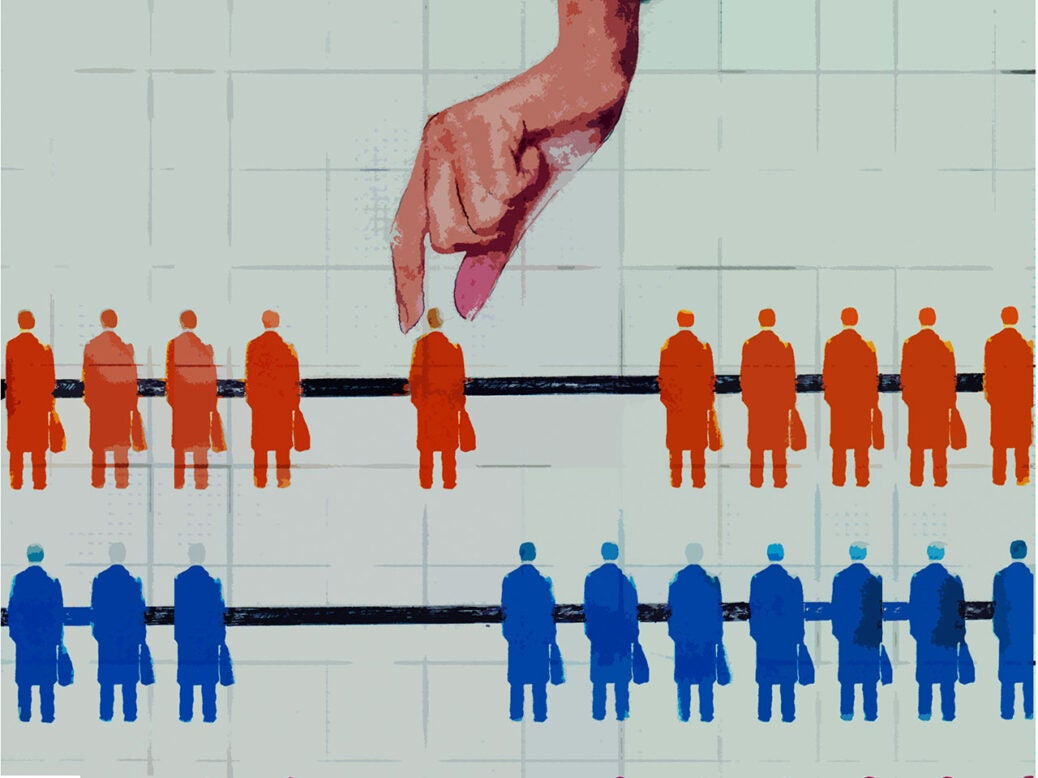

One stat that caught my eye this week: one in four Republican voters say they are “not open to Donald Trump” as the party’s nominee, with three in ten of these voters saying they would vote for Joe Biden over Trump in next year’s presidential election. In other words, 7 per cent of Republican voters say they will vote Democrat next year (think Republicans like Liz Cheney). That is huge – enough to decide ’24 if it holds true.

NB: If this email doesn’t load for you in full, you can view it online (or in app) by clicking on the button you see when your email cuts off. Will has written today’s sign off, on Paul Theroux and VS Naipaul’s fractured friendship.

If the pieces below intrigue, perhaps you’d like to try a trial subscription to the NS. Read three free articles after registering on our site. A digital subscription is only 95p a week. Let’s get to it.

1—“America is nothing more than a self-help society.”

For our Weekend Essay, Sohrab Ahmari examines the return of cultish self-improvement fads inside the American middle classes. Radicalism has given way to wellness crazes and bodybuilding with political inflections. Not for the first time, Ahmari argues, the bourgeoisie have traded politics for the cultivation of their inner lives. WL

“Working on yourself” these days bears surprising political valences. On the left, it often means “unpacking” the biases that blinker even the most well-meaning liberals, a process involving arduous examinations of conscience and public contrition. For those who belong to marginalised groups, meanwhile, self-help progressivism offers uncritical affirmation and uplift: their subaltern stories are to be foregrounded, while those from dominant groups are told to listen.

Yet the rise of self-help politics is as much a phenomenon of the online right as the left. If you know your way around Twitter’s darker corners (or parts of Lower Manhattan), you will have encountered a renascent racialist right. This scene is devoted to liberating the white man’s heroic spirit from the “longhouse” – an anthropological metaphor for the loss of autonomy and adventure that supposedly attended the long-ago transition to sedentary, agricultural civilisation.

2—“What is the EU doing, exactly?”

The most important resource to Russia is oil, not gas. Most of it is transported out of Russia by ship. Most of those ships are Greek, owned by oligarchs who, under the Greek constitution, do not have to pay income tax or capital gains tax. Will Dunn sheds light on a startling reality. HL

“Oil is the single biggest source of revenue for Russia,” Brooks tells me, “[and] the Greek shipping fleet is the single biggest provider of transport to Russia, even including Russia’s own ships… nobody comes close.” Brooks’ research shows that before the war in Ukraine, Greek shipping companies provided around a third of the shipping capacity for Russian oil exports; he says it’s now more than half. The uncomfortable fact, Brooks tells me, is that “Russia depends on Western transport infrastructure to keep its war going”.

Most Greek shipping firms are private, family-owned businesses, and they seem unconcerned by the moral implications of their trade. Greece, Cyprus and Malta comprise less than 3 per cent of the EU population, but – in what Brooks calls an example of “extreme dysfunction inside the EU” – they have successfully restricted decisive action against the Russian economy on behalf of a handful of well-connected companies.

3—“They had attractive girlfriends and wives, nice cars, and almost always owned their own house… I inspired genuine pity.”

Britain’s petite bourgeoisie are the most under-examined class in the country, the sociologist Dan Evans explains to Anoosh in our Weekend Interview. A media class obsessed with the housing crisis, landlords and climate change has spent the last decade missing another story, of upward-mobility, in a parallel Britain. WL

Evans derided Westminster’s target voter caricatures such as “Mondeo man” and, more recently, “Stevenage woman”. “It’s cod sociology, rather than looking at the UK in terms of class,” he said. “What they are really talking about is the petty bourgeoisie; it’s on the periphery of their vision, they know it exists, they talk about it every four years, but the problem is they don’t understand it.

As a socialist embedded in conservative values, and an ex-Corbynite dissenter, Evans felt like a lone voice. “The left has given up trying to understand popular conservatism,” he said. “There is a desperate lack of reflection on where the left has gone wrong, and its relationship to people outside the circles it occupies.”

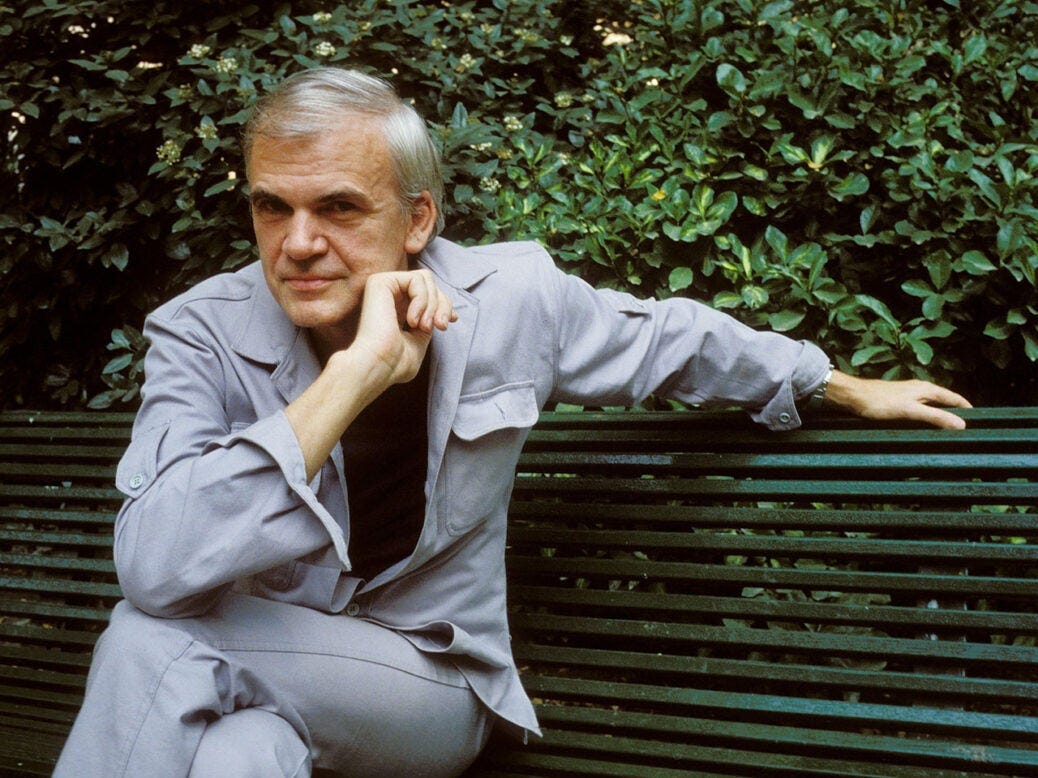

4—“A strange posthumous role in the new Cold War has thus been assigned to a novelist who went awol from the old one.”

This is fascinating by Christopher Caldwell, who dismantles much being written about the supposed relevance of Milan Kundera’s work to Ukraine’s current fight for survival. HL

Kundera was a sex novelist. Until he left Czechoslovakia in his forties, he spent more of his career building communism than he did resisting it. In half a century of French exile, Kundera cared more about the Great Divide between the sexes than about the Iron Curtain that had fallen across Europe. His specific sexual ideas – which tightly link domination and arousal – come off today as repugnant, repugnant to the very Western “values” we claim are at stake in Ukraine. In exile, Kundera insisted again and again that he was a writer, not an ideologue. Is his posthumous politicisation a zealot’s misreading? Or are we missing something?

5—“There is growing bipartisan consensus in the US that trying to avoid a great-power war is a waste of time.”

Foreign Affairs carried a good piece last month on how the US war machine, now in private hands, is struggling to supply Ukraine. Malcom Kyeyune picks up that thread here, and claims the West can no longer make war (forget about Taiwan). I’m not completely convinced: necessity tends to be the mother of invention. HL

The Second World War was the ultimate industrial war, and so it pitted the entire productive might of the world’s greatest powers against each other. No new washing machines or car models were released during the height of America’s participation: industrial capacity went completely into the effort to destroy the Axis powers. Jukebox and typewriter factories produced M1 carbines in endless quantities; car manufacturers became tank manufacturers overnight. None of that is possible for Western countries any more.

6—“Campbell’s issue isn’t her privilege – it’s her total lack of self-awareness.”

Esther Watson takes a sharp, subtle look at the career of Grace Campbell, daughter of Blair’s spinner, stand-up comic, and perennial fixture of British newspaper weekend supplements. Watson diagnoses something that Campbell can’t quite recognise: she has no idea who she is. WL

Campbell has set out to be a new kind of icon for young women, embracing a version of female empowerment that was epitomised by Lena Dunham’s seminal Noughties sitcom Girls. Campbell has praised Dunham in the past for her “honest and comical” depictions of sex and for making “an irrational and unhinged woman like me feel a bit more normal”, and she clearly draws inspiration from her: “I’m very open and I think that might make people feel less like freaks.” Like Dunham, Campbell speaks openly about sex, mental health, and bodily functions we don’t necessarily need to hear about. But unlike Dunham, Campbell lacks the brilliance of a cultural phenomenon such as Girls to fall back on.

7—“Why does David Walliams retain such a grip on our children’s imaginations when his own is so impoverished?”

And they say the hatchet job is dead. This is glorious from Tom Gatti on the books David Walliams writes, nominally for children. HL

It is difficult to imagine a large language model AI turning in anything as lazy as Walliams’s prose. He loves onomatopoeia but employs it in a deadeningly literal way: “Peter gulped in fear. Gulp!” When he invents a word – “pongtasmagoric”, for example – he is so pleased with himself he includes an arch footnote flagging it. The rest of the time he is careful not to exert himself. Walliams is happy with “dreaded double history”, so why shouldn’t it be followed by “dreaded worksheets”? When a “damp, limp vegetable” is thrown, why wouldn’t it leave “a damp, green, vegetably mess”? In the fictional theme park of “Loopyland”, the most spectacular attraction is called the “Loop-the-loop Loopy Coaster”. This is the Boaty McBoatface school of writing.

8—“Liberalism did not fail; it was assassinated by a large and open conspiracy.”

Master essayist George Scialabba takes on Patrick Deneen’s new book, Regime Change. Deneen may be the premier critic of liberalism writing in the United States today, but Scialabba unwinds his thinking in such a quietly devastating way that I will never be able to read him in the same way again. WL

Deneen is a little bit equivocal about democracy. He would replace the negative liberty and procedural equality of liberal democracy with a “common-good conservatism” based on “classical or Christian liberty”: “A condition of self-governance… requiring an extensive habituation in virtue, particularly self-command and self-discipline over base but insistent appetites.” Only virtue, he instructs us, makes true liberty possible.

But does it? Saints have been tyrants, again and again: the Christian Roman emperors who persecuted unorthodox Christian theologians; the medieval Catholic prelates who exterminated the Cathars and Albigensians; the inquisitors who burned Jews, scholars and hapless peasants; Geneva under Calvin; the ascetic Brahmins who for centuries have treated the lower castes with barbarous contempt and cruelty; the Iranian mullahs, obsessed with female modesty and homosexuality. Virtue may be a necessary condition of political liberty, but it is hardly a sufficient one.

Will and Leila’s Best of the Rest

Times: Sunak embraces the drill. Sadly this is an actual drill, not a music video made on Snapchat.

Foreign Affairs: The BBC and the decline of UK soft power.

New York: How trauma became the way America makes sense of itself.

Lit Hub: A brief history of crying while reading.

Seamus Perry: Two Evelyn Waughs. This may contain the best last line of an essay this year.

Tom Stevenson: The secret life of diplomats.

Francis Fukuyama: AI and democracy.

David Samuels: The Obama factor. Vital reading on a seriously misunderstood president.

Elsewhere on the NS

Keir Starmer will bury Blairism, writes Jonathan Rutherford. In office, circumstances will force the Labour leader to break with his party’s liberal progressivism.

Retromania was coined to describe our rampant pop culture nostalgia – now it fits our politics, thinks Fergal Kinney. We are living in the Nineties on repeat.

Polling is the “junk food” of journalism, argues John Oxley, and ruining our politics.

The deceptions of longtermism – the defining idea behind effective altruism – may well be devastating, Émile P Torres believes.

Kate Mossman meets Antonia Fraser.

How did Barbie become a phenomenon? By being loud before it was good, writes Sarah Manavis: “Marketing teams increasingly prioritise social media campaigns over critics’ reviews… At a London press screening of Barbie attendees were heavily encouraged to share their ‘positive feelings’ online, even though it would be days before the embargo would be lifted on reviews.”

Oxford has appointed a new professor of poetry: AE Stallings. Emily Formstone introduces us to her.

When is Ukraine going to break through Russian lines? Lawrence Freedman offers a history of attrition.

How to get into: David Foster Wallace (without reading Infinite Jest)

Each week we ask someone to recommend three books as a way into a subject. This week we turned to Chris Bourn, who puts the Saturday Read together with us.

There are good reasons for not getting into the writing of David Foster Wallace. His celebrated style – a verbose hipster fugue – is off-putting to many, even occasionally to converts. Damning recent accounts of Wallace the man have wrecked his cultural standing. And his most popular work, Infinite Jest, is a 1,100-page barrier to entry in the mould of Ulysses or Being and Time. It sat on my bookshelf for a year before I managed to pick it up, and it took me longer than that to read it.

But, almost exactly 15 years after his death by suicide, the influence of his voice and his omnivorous critique of pop culture is still fizzing. There remains no surer way to sharpen your understanding of culture, language and psychology – how they mesh and mash to create our shared experience – than an immersion in Wallace-world, especially his non-fiction.

“Derivative Sport in Tornado Alley” in A Supposedly Fun Thing I’ll Never Do Again (1997): A short, accessible (for him) autobiographical introduction, sketching his childhood as a “near-great junior tennis player” in Illinois – which also serves as a primer for Infinite Jest and its otherwise baffling tracts on clay-court geometry.

“Authority and American Usage” in Consider the Lobster (2005): This deeply unpromising essay begins with some observations about dictionaries, and balloons into an almost comprehensive explanation of socio-political divisions in Western democracies.

The Pale King (2011): Wallace’s unfinished, posthumously published third novel is his best, conjuring poetry and life from the dourest of subjects: the US tax code and deathly office boredom. It is much, much better than that sounds.

And with that…

VS Naipaul disliked “fine” writing. No John Updike then. He disliked “experimental” writing. No James Joyce either, nor any Samuel Beckett for him. Naipaul, who was born in 1932 and died in 2018, rarely had time for his contemporaries. He ignored or disdained them. He was from Trinidad, an island naked without literature. He was a new man, self-created, who developed a new style to clothe his homeland in. Who did he read? Thomas Mann, Proust, Chekhov, Trollope, Dickens, Shakespeare. Certain Latin poets had an appeal: Martial, Horace. Oh, and there was the King James Bible. “It’s frightfully good,” said Naipaul.

I learned this reading Sir Vidia’s Shadow: A Friendship Across Five Continents by Paul Theroux. When he was young and adrift in Uganda in 1966, Theroux, 25, met Naipaul, then 34 – “so certain, so intense, so observant, so hungry, so impatient, so intelligent”. Theroux became his helper, his driver, his guide, his translator, his listener and, in a skewed way, Naipaul’s friend. In return Naipaul gave Theroux the permission every young writer needs to start: he tells him he has the gift.

The partnership between the two men, always uneven, eventually capsizes. Sir Vidia’s Shadow tells the story of a literary friendship gone wrong. It’s a tribute that doubles as an attempted execution. And the tools of literary assassination are always the same: envy, bitterness, resentment. Startling and unembarrassable, with intimately high stakes, Sir Vidia’s Shadow is the most unnerving book about writing and writers I have ever read.

Thank you for reading. Don’t miss out – subscribe to the New Statesman and stay up to date with everything you need: from news and analysis to comment and criticism.

Whether you’re looking for a sharp blog or a finely written feature, the New Statesman has you covered. Have a good week, and catch you next Saturday.

Thanks to Chris Bourn and Leila Moore.

How the Left Forgot the Petty Bourgeoisie is an excellent piece.

George Scialabba's take on Patrick Deneen isn't a "quietly devastating" "unwinding" of his book - at least if your snippet is anything to go by - so much as a failure to understand the essence of the Post-Liberal critique of liberal individualism. He goes down a silly and tendentious rabbit hole about Christian history which completely misses the big picture. The critique of Western liberal individualism (as it turned out anyway) is that:

1) hardly anyone really wants the Equality implied as the ideal end-state of liberal democracy; they just want the nice feeling they get about themselves from saying the word.

2) very few people can really cope well with the 21st c. hyper-liberal version of Freedom either; it's too hard, too disorienting, too lonely and conflicts with the huge human need to feel like an insider of a group. https://grahamcunningham.substack.com/

John Gray would have written a much more penetrating one.