The Saturday Read: Farage's tune

Inside: Gary Lineker's last act, Wes Anderson's return to form, Thatcher's children, the escalation in Gaza, the slow death of the semicolon and David Tenant in conversation with Gordon Brown.

Good morning. Welcome to the Saturday Read, the best of the New Statesman, in print and online this week. This is Finn with Nicholas and George.

Unsustainable net migration figure falls to… unsustainable net migration figure. That’s how the median British voter will feel this week, according to our polling whizz Ben Walker. The ONS published its latest numbers on Thursday, and estimates that net migration has halved from 860,000 in the year ending December 2023 to 431,000 in the year ending December 2024.

This direction of travel should be a win for Labour, at least at the polls. But the party has to be careful – there is no use in sounding like Reform-lite. How can Keir Starmer wrest back the immigration conversation from Nigel Farage, and make it on Labour’s terms? Come back tomorrow for Ben’s full analysis on this thorn in the government’s side.

As ever, thanks for reading and have a great weekend.

1—“You’re sounding Scottish”

Somewhere between the international speaking circuit and the filming schedule for the next Jilly Cooper bonkbuster, Gordon Brown and David Tennant crossed paths. Kate Mossman took notes as they discussed Shakespeare, the Church and philanthropy. NH

“Politics and playwrighting have always gone together. Shakespeare’s history plays are all pretty political, John Osborne shook the cage in the Fifties, the agitprop theatre of the Seventies and Eighties was making – often quite unsubtle – political points. These days we’ve got James Graham and Jack Thorne and a slew of writers who are continuing the tradition of writing about the world and society in a way that’s political and personal. Drama is always political because it’s about human beings and how we interact with the world around us.”

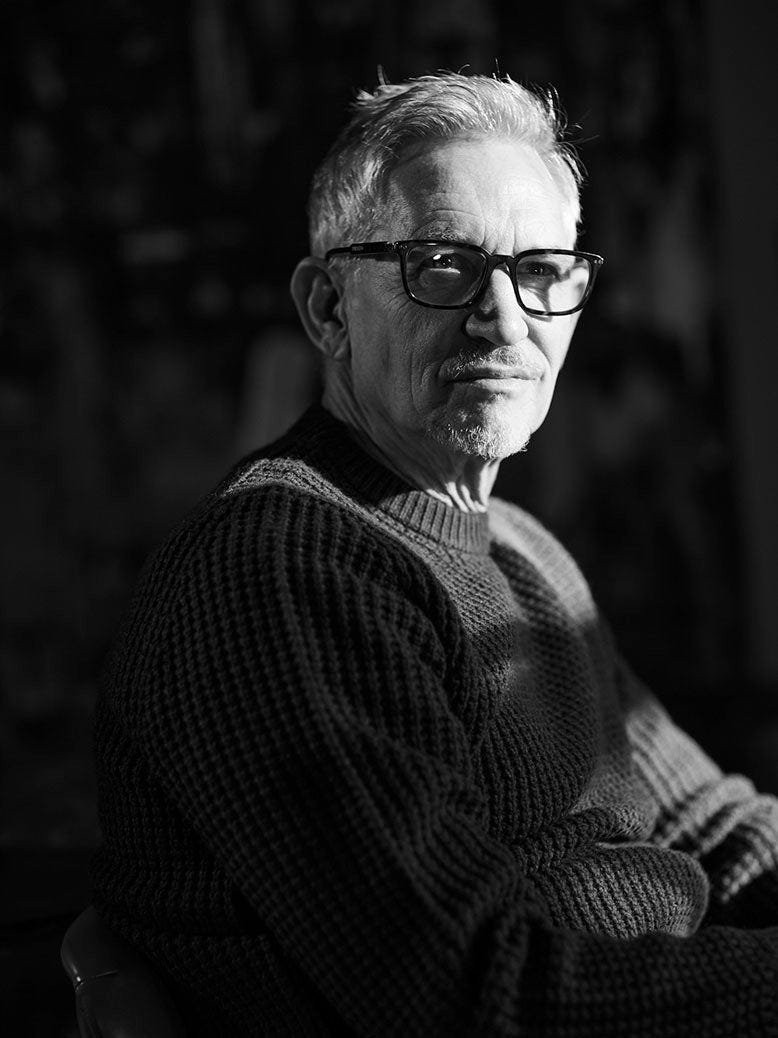

2—“They think it’s all over”

Gary Lineker has lost control of his carefully choreographed exit from the BBC – he will present his last Match of the Day this weekend. Jason interviewed him late last year. He reflects on their meeting here, and finds a man who friends describe as “immaturing with age.” FMcR

For all his accomplishments, the naivety remains. I didn’t find him at all grand or self-celebrating in our interview last year. He answered questions candidly and even guilelessly. If there was a deeper calculation, I was not aware of it. A shrewder, more sophisticated operator would surely have been more circumspect on social media and not have blundered so abjectly as he has in recent weeks.

3—“Uncomfortable, intriguing”

The problem of contemporary fiction is that there’s no such thing. So reckons novelist Sarah Moss, who reflects on the efforts that went into her upcoming book Ripeness, and the impossibility of capturing a world that insists on slipping through our grasp. The present will always elude us. Why – and how – do we keep trying? GM

There will be novels about what has happened in the Middle East in the last two years, as there will be novels about Trump’s re-election and whatever happens next in Ukraine. They will be written by people who have, through experience or research, an understanding of the intimate, material detail of individual lives in those times and places, because fiction runs on intimate, material detail. Other people living other lives, including me, will continue to write about other matters, all of which continue to be related to each other.

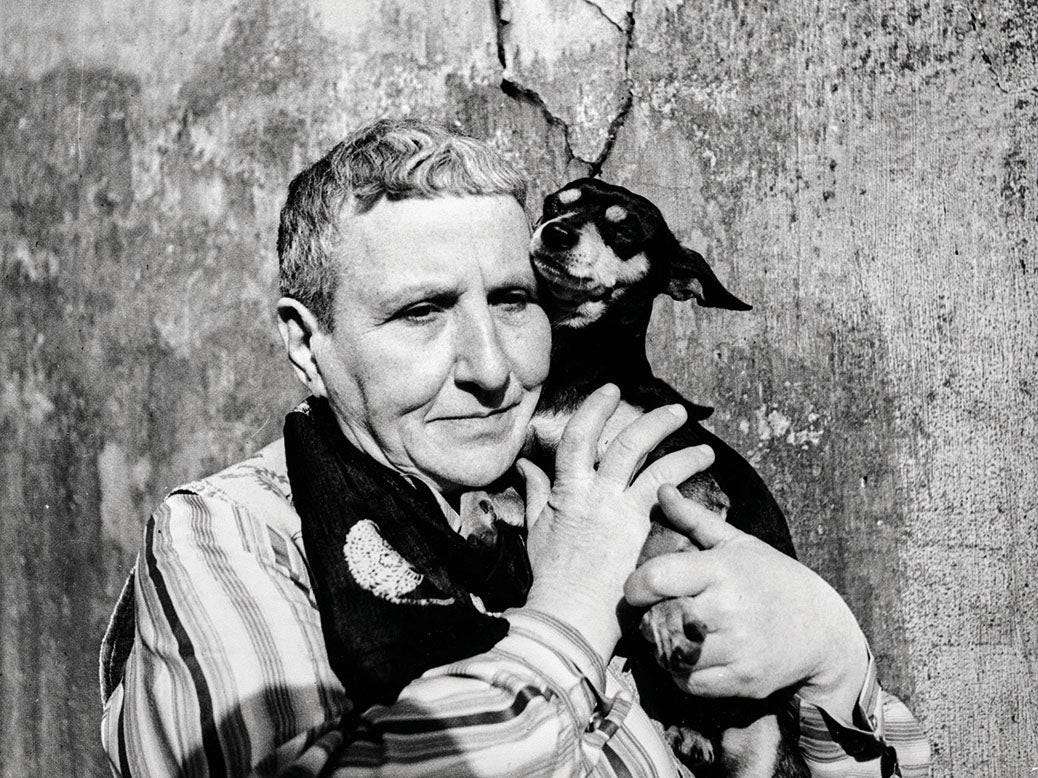

4—“That’s me”

For this special piece, we asked a glittering cast of writers to provide and reflect on photos of their childhood selves. I liked Michael Morpurgo’s, quoted below (and pictured above), and we also have Bernardine Evaristo, Frank Cottrell-Boyce, Mark Haddon, Geoff Dyer, Malorie Blackman – to name just a few! GM

My best days: going to the milk bar, watching the trains come chuffing by. I’m aged five. It’s 1948. I’m living at 44 Philbeach Gardens, London. It’s my first year of school, at St Matthias with St Cuthbert’s LCC school. That’s on the Warwick Road. Mum always walks us to school. And we do hop-scotching on the way sometimes.

5—“Lapsing into self-parody”

Wes Anderson’s recent cinematic efforts certainly left me wanting. The French Dispatch was boring, sprawling and simply too episodic. But with his latest release, The Phoenician Scheme, Anderson has found his groove again, David Sexton argues. FMcR

Unlike its predecessors, it has a story to tell, rather than being an anthology of incidents. It uses all of Anderson’s stylisations but is not primarily about them, as his later films had started to seem. He takes his own cinematic language almost for granted here, rather than foregrounding it relentlessly. In a recent interview, he seemed almost to acknowledge that his “visual handwriting” had become a burden, a distraction from content.

To enjoy our latest analysis of politics, news and events, in addition to world-class literary and cultural reviews, click here to subscribe to the New Statesman. You’ll enjoy all of the New Statesman's online content, ad-free podcasts and invitations to NS events.

6—“Decades of political neglect”

The NS’s house photo junkie Gerry Brakus has put together a marvellous visual essay from Craig Easton’s photography series Thatcher’s Children. It follows families in England’s north from infancy to parenthood, from the Nineties to today. GM

Developed through long-term relationships with the families, the project approaches their lives with dignity, not judgement. One mother, Kirsti, captures both the joy and quiet despair of parenting under pressure: “The only thing that puts a smile on your face is seeing your kids happy. When I was younger we didn’t even have 1 per cent of a chance to have a good life. And at times I worry that I can’t give my kids a chance either. You don’t want to put your worries on them. Later on they’ll learn.”

7—“Can forests think?”

Due to his urban upbringing, my colleague George has a strange predilection for diving into icy waters, chatting to woodland, and generally hanging out with Gaia. But in the nature writer Robert Macfarlane, who thinks rivers are “alive”, he’s found a comrade. NH

He led me to what looked like a pond. In fact it was a surfacing of the book’s chalk stream. He dropped to his knees and tapped the water. A large black fish swam up, sort of belched its mouth out beyond its lips, and bit Macfarlane’s finger. I realised, with horror, that it was now my turn. “Hold your nerve,” he said, as I extended a tremulous digit towards the fish, who thankfully was no longer interested. I withdrew my arm the moment I was told I had passed “the great carp test”.

8—“Stein’s formidable output”

This piece made me feel a little less guilty for not having read Gertrude Stein, but a lot keener to do so. Margaret Drabble has reviewed a new book about the great modernist’s rise. This description of an estrangement sold me: “Little by little we never met again.” GM

Gertrude Stein is, famously, one of those authors whose name is better known than her works. This was so during her lifetime, as the biographer Francesca Wade demonstrates in her readable and illuminating account of Stein’s life and literary afterlife. Wade explores how we have come to perceive Stein, as a writer and as a character. And a “character” she was: a self-created literary phenomenon, keen to have her name in the press and to have herself talked about, for good or ill.

9—“Not in my name”

British Judaism is no monolith, but many want an end to the senseless killing in Gaza, Hannah writes. Since 7 October, Israel’s response has become “increasingly disproportionate: indefensible”. The same feeling is spreading among our leaders, too. GM

The Jewish people know more than anyone how damaging collective silence can be. The only thing necessary for the triumph of evil is for good men to do nothing. I know that whatever I write will not make a difference. I’m sorry Dad. How could it? What can any individual possible say or do to stop the killing and see the hostages returned? British Jews are not a monolith. But I know there are others who feel what my father and I feel, too. Who are ashamed of what the current Israeli government is doing. And who want to say: “Not in my name.”

10—“Dickens’s Britain”

The NS’s acting editor Tom Gatti is off to pastures new. In his final editorial note he reflects on his 11 years at the Statesman, Gordon Brown’s guest edit on child poverty, and – in typically literary fashion – the long shadow of Dickens. FMcR

The New Statesman staff are sometimes drawn to the windows of our first-floor office in Hatton Garden by events unfolding outside: a purple Lamborghini pulling up to the jeweller’s next door, a music video being filmed on phones in the middle of the road, groups of men striking deals or squaring up to each other while security guards coolly observe. I’m always aware, though, that what we’re looking at are Dickens’s streets.

George’s Best of the Rest

Larry Elliott: Cutting aid for girl’s education is bad economics

Jeremy Bowen: Goodwill running out towards Israel

Duncan Robinson: Bring back Boris Johnson

Vinson Cunningham: Why I can’t quit the New York Post

David Thomson: Terrence Malick melts away

Meaghan Garvey: Morgan Wallen is the problem

Britain needs an al fresco dining revolution – and pronto!

A scientist fighting nuclear Armageddon hid a 50-year secret

And with that…

An extinction scare is upon us! I refer not to the hawksbill turtle or the scalloped hammerhead shark, but a far more delicate beast: the semicolon. A new study suggests that our most rarefied punctuation mark is in terminal decline. Some squad of syntactic scientists have found that 67 per cent of students in Britain never or rarely use them; this was followed by a further survey of London undergrads in which half of respondents didn’t even know how to use them.

As evidenced above, I do know how to use it: as a handy adhesive for two independent clauses which feel like they should go together, and also (for some reason) when doing big lists that need harder bracketing. But the case for the semicolon is not only practical but aesthetic. This is an Atlantic struggle: between what Zadie Smith, in her introduction to Edward St Aubyn’s The Patrick Melrose Novels, calls the “puritan brevity of the American sentence” and the “English sentence, [with] its twists and turns, its subtlety and comedy”.

If you believe in the latter, you believe in semicolons. As Smith writes, “Oh the semicolons, the discipline! Those commas so perfectly placed, so rhythmic, creating sentences loaded and blessed, almost o’erbrimmed, and yet sturdy, never in danger of collapse.” Imagine if anyone, let alone Zadie Smith, said that of a sentence of yours. So come on kids: buy yourself a copy of Fowler’s Modern Usage and get to grips with the semicolon, the only punctuation mark that winks.

The New Statesman is home to the finest writing on politics, culture and ideas. To stay up to date, subscribe using the link above.

— Finn, Nicholas and George.

The Guardian having become a more or less unreadable cosmo-comic, and The Observer having been more or less obscured along with its best writers, you fine people offer a warmly oaked port within which one may moor a leather wingback and briefly forget our extending anachronism.

'Charlotte' from the estate agency called yesterday. Upon my answering with a simple 'hello', she set herself off like a Radio 2 teenager who sounds perpetually on the verge of climax: 'Hiya, y'alright... I've spoken to... blah blah...', after which, having no idea, I disarmed her with a long pause and 'excuse me? Who are you?'

For some reason, it is un-politically correct to call out how dismal this country has become, and thus its trajectory. But I'll do it anyway. Farage is coming. The New Statesman makes it all better for a bit. So, ta very much, mate, as I'm sure is now the English tutors' vernacular from whence I hailed. I shall imagine Mr Simpson looking down upon me now smiling wise counsel and rubbing his yellow fingers in catholic delight. Sorry to rant. "Je suis Nicholas".

By the way, the BBC has been playing the "impartiality" card for so long that were this country not split into its supporting feudal overlords, and (sub)urban bumpkins, it would have been held to account. The rot is entrenched; the BBC has been discernibly (albeit with nuance and requiring a basic level of critical contortion) far from impartial for at least one decade and arguably two.

For as long as publicly identifying someone to their face as a shameless liar continues to be perceived as worse than goat buggery we shall get what we deserve.

"He did not seem to understand that the issue here was not one of free speech or even his trenchant opposition to Benjamin Netanyahu; it was about his role at the BBC and its charter commitment to impartiality"

How can anyone be impartial about genocide?