The Saturday Read: Is Britain a Tory nation?

Plus your usual raft of picks for the Easter weekend.

Good morning, and welcome to the Saturday Read, the New Statesman’s weekly guide to the best writing on ideas, politics, books and culture. This is Harry Lambert. If you are receiving this newsletter for the first time, the Saturday Read is our new weekly highlights email. Each week we will send you a selection of our essential reads, 15 links to intriguing pieces in other outlets, and a handful of other NS articles we think you might like.

Will Lloyd, my co-writer, has posed this week’s question in the sign-off below. Do you think Britain is a Tory nation? Leave a comment and let us know, or get in touch by replying directly to this email. We’d also welcome your thoughts on any of the pieces below. If they interest you, you could try a trial subscription to the NS. Read three free articles after registering on the New Statesman site. A digital subscription is just 95p a week. Let’s get to it.

1—“In the 1990s Margaret Thatcher would sometimes declare: ‘Come on, we are going to march up Downing Street and reclaim No 10.’”

A decade after her death, George Eaton unpacks Margaret Thatcher’s legacy. The Tory leader redefined the limits of what was possible in British politics, although Thatcher was not quite as radical as she is remembered by contemporary Conservatives (she refused to sell off Royal Mail because she was “not prepared to have the Queen’s head privatised”). Yet the economic revolution she began was powerful enough to assimilate all potential challengers, including those in the Labour Party:

Blair boasted that his government would “leave British law the most restrictive on trade unions in the Western world”. Public investment was neglected in favour of the profligate private finance initiative and the City of London indulged as never before. “I always thought my job was to build on some of the things she had done rather than reverse them,” Blair confirmed on the day of Thatcher’s death.

Twenty-six years earlier, in the London Review of Books, Blair had written of the “tremendous danger” in believing that Thatcherism “is somehow now invincible, that it has established a new consensus and that all the rest of us can do is debate alternatives within its framework”.

2—”There has clearly been a lot of abuse, and our position is no one should be subject to that.”

The lines of tension in the fight over trans and sex-based rights are familiar. But is there more harmony between the two sides than there appears to be? Is there a landing zone for an agreement on the issue within Labour before the 2024 general election? I spoke to Rosie Duffield, Ben Bradshaw and others in the party for this new long-read on the vexed subject.

The disagreements between the two feel as if they become less severe as they get more specific. Bradshaw accepts that trans women may be excluded from specific spaces under the Equality Act (“Yes, in certain circumstances”) and does not think JK Rowling’s recent creation of a single-sex women’s refuge in Scotland was transphobic. (“There’s no problem with Rowling doing what she wants to do,” he says. “It's just not what most refuges are comfortable with.”)

Bradshaw is also open to the fact that sporting bodies may find it necessary to limit their competitions to those born female. (“Domestic and international sporting bodies are feeling their way very sensitively based on the evidence on all of these issues.”) He also thinks Isla Bryson, the convicted Scottish rapist who identified as a trans woman when awaiting her trial, was rightly removed from a woman’s prison. (“As far as I understand it, she was always kept segregated.”)

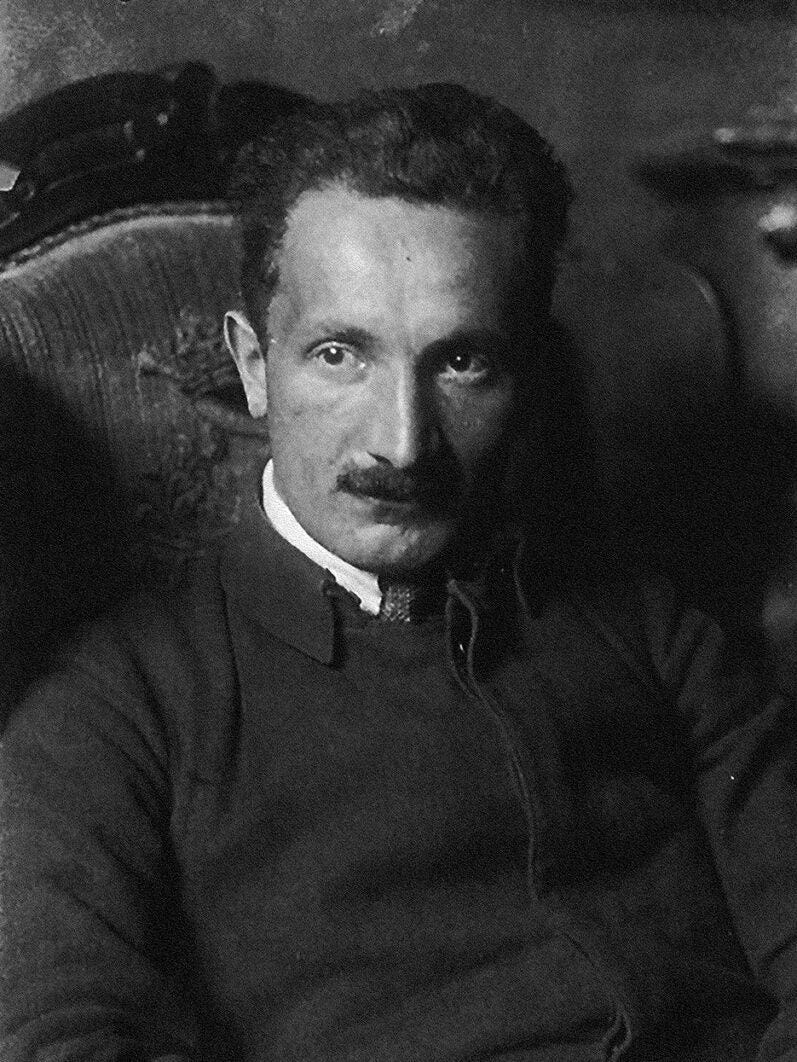

3—”Is this the moment of reckoning? Should we be afraid of Martin Heidegger?”

For our weekend essay Lyndsey Stonebridge considers the many afterlives of Martin Heidegger, the German thinker whose heavy flirtation with Nazism probably makes him the most radioactive philosopher of the 20th century. Stonebridge is good on the contemporary hard-right’s fandom of Heidegger, whether that’s in Russia (Alexander Dugin) or the US (Richard B Spencer and Steve Bannon). Still, Heidegger’s call for existential courage, however contaminated, does not belong to extremists alone.

Dugin first discovered Heidegger in the 1980s. Young, clever, restless and already a bit crazed, he spent the last grey days of the Soviet Union locked in a darkened room reading philosophy. Heidegger’s writing was not available in Russia, but Dugin had found a microfilm of the philosopher’s masterpiece, Being and Time (1927). He didn’t have access to a microfilm reader, so he rigged up a hand-cranked film projector and read Heidegger’s words projected on the wall above his desk, blinking out of the dark, mesmerised by the ideas that unfolded before him.

4—“We watched a man gradually cut himself to death – and for what?”

Katherine Cowles, our theatre critic, attended the play everyone is talking about (A Little Life, based on the novel by Hanya Yanagihara). Read her review and spare yourself a visit. This is a play better dissected for its bizarre popularity – as a book, and as a prospect for the stage – than it is enjoyed.

I would be worried about spoilers, but I’m not sure it’s possible to “spoil” so macabre an evening any more than it’s possible to spoil a funeral: there are no prizes for guessing the ending, and frankly there’s not much fun to ruin. Besides, there are trigger warnings before you even enter the theatre (the Harold Pinter, West End) that give a gloomy glimpse into the proceedings: “physical and emotional abuse… will be portrayed realistically and emotively which some viewers may find disturbing”. You think?

I doubt those who spent up to £175 per ticket will be put off by these omens if the 750-page book that inspired them didn’t do it. Some audience members are hemmed even closer into the action in the immersive on-stage seating, which creates an impression of intimacy and voyeurism, but also serves to emphasise the problem with this gruelling adaptation: we are held captive. Unlike with a book, we cannot look up from the horror or walk away. If this were television, I would have switched off at the ad-break. Told in this form, A Little Life feels like a litany of grief – relentless, to the point of tedium.

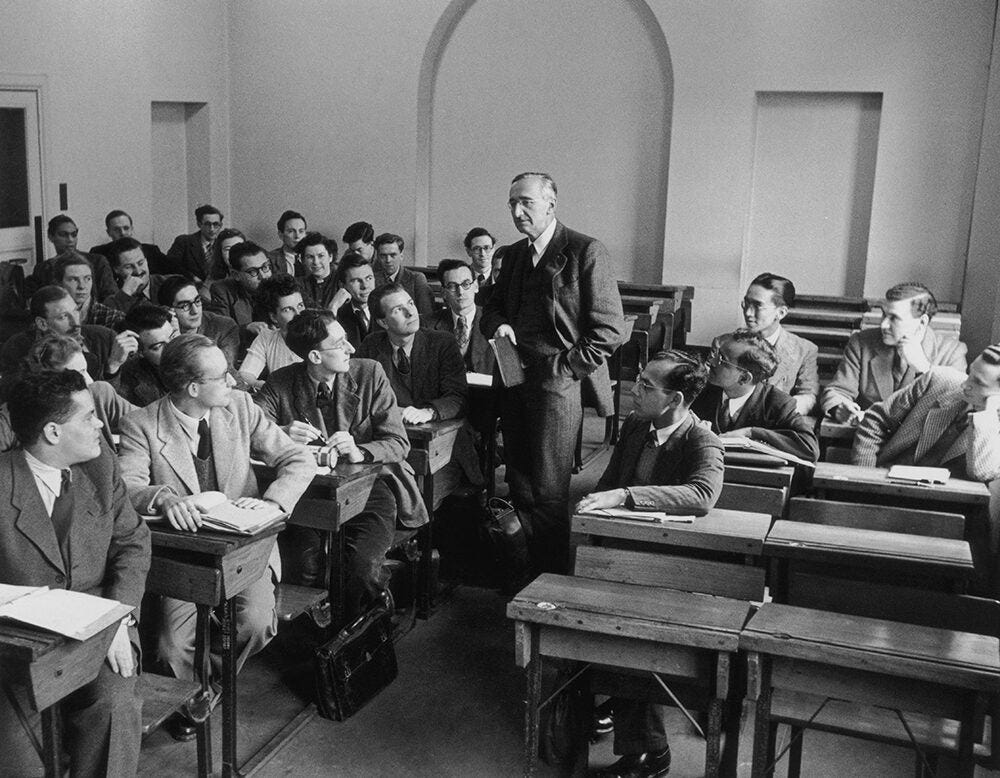

5—“Hayek was nothing if not a puzzler, someone who kept going back to problems as opposed to offering a definitive synthesis.”

What jumps out from this Jan-Werner Muller essay on Friedrich Hayek, the godfather of neoliberalism, is not merely how effective the Austrian was at building institutions and juggling the ferocious egos within them, but how much “Fritz” disliked the US, where he would become an intellectual hero to generations of economic policymakers.

Hayek’s impressions of the US make one read his dedication of Constitution of Liberty to the “unknown civilisation that is growing in America” in a new light. The Viennese visitor felt that his belief in “the vast intellectual superiority of the Europeans” had been confirmed; he complained to Mises about the “tastelessness and banality” of American life and, in a heroic act of old-world resistance, grew a moustache to “protest against American civilisation” (or lack thereof, considering the real meaning of the dedication). Hayek concluded that “America is a country to earn one’s money but not to live” (a comment that proved oddly prescient about Hayek’s later decision to maximise his salary at the University of Chicago to financially support the family he had abandoned in Europe).

Probably to the annoyance of aficionados of notions like the “Anglosphere”, Hayek also contrasted the cultural wasteland of the US with an England which he had come to idealise even before he visited.

6—“If someone leaked my message history,” one friend said, “I would quite simply die.”

Human beings, a friend once said to me, are not meant to remember everything. I think he was right. But the internet isn’t written in pencil, it’s written in pen. The consequences of that are most alarming on WhatsApp, “the app that ate everything” as Jonn Elledge puts it. (Pro tip: You can set your messages to disappear.)

Even in the personal sphere, there’s something terrifying and oppressive about the idea that off-hand comments could be recorded forever. WhatsApp preserves not just moments of romance and joy but of bitterness and conflict, too, and there’s something unnerving about having a box in your pocket containing a record of all the worst rows you’ve ever had. Perhaps it would be healthier to delete the lot. Once upon a time, our memories were enough.

7—“The ‘return to tradition’ looks suspiciously like something dreamt up by 1950s advertising executives.”

A trad wife – short for traditional wife – is, according to the TikToker Estee Williams, “a woman who prefers to take a traditional or ultra-traditional role in marriage, including the beliefs that a woman’s place is in the home”. When this trend surfaces on Instagram, Twitter and TikTok, you’ll often see it wrapped up in Christian theology. It’s a spurious association, argues Rose Lyddon, as Christianity has never been quite as family-friendly as it might seem:

For St Augustine, the monastic life pointed towards the kind of society that would characterise the world to come. This isn’t the spiritualised “Heaven” that people mistakenly think Christians believe in, but the real flesh-and-blood Kingdom of God where we will live after we’re resurrected from the dead. There will be no sexual reproduction or death, certainly no marriage. Freed from the drive to self-preservation and the limits of scarcity, we will be able to enter into relationships based on mutual self-giving love. As RA Markus wrote, the monastery “defined the permanent challenge to all other forms of social existence”.

8. “Have the streaming wars brought us better TV, or more muzak?”

Will Dunn, our business editor, has turned his attention to the streaming wars (remember those?). More than five million British households now subscribe to Netflix, Amazon and Disney Plus – but to what end?

If Netflix was so much cheaper, how was it able to spend so much more money? Partly the answer is that money itself was cheap: with low interest rates and quantitative easing, central banks created a global economy in which borrowing was practically free and investors were happy to gamble, especially on promising technology companies. Netflix was able to raise tens of billions from selling its equity and debt.

Thanks to Netflix, Amazon and Disney, we watch more American TV than ever before. Of the 50 most popular titles streamed in the UK over the last three years, only seven were set in the UK; the top two are The Crown and Bridgerton, American dramatisations of British history.

Best of the Rest

Guardian: The cost of the crown. The Graun’s fruitless bid to make a republic of us goes on.

Times: Half of voters don’t understand the point of Starmer.

New Yorker: Inside Hillsdale College. American conservatives are much better at building institutions than their UK counterparts.

Insider: Peace, love and Hitler: How Lex Fridman’s podcast became a safe space for the anti-woke elite. Who knew Fridman, the thinking man’s Joe Rogan, used to write erotic poetry?

Politico: Voter ID comes to England.

Rishi Sunak: What I learned from Nigel Lawson.

Petronella Wyatt: I’ve never forgiven Trump for making me pay for his taxi. The worst thing Trump has done yet.

Tyler Cowen: Game theory and the AI pause.

Erin Somers: My wild weekend at the Philip Roth festival.

Farage’s perfect G&T. He stresses the importance of “cold ice”.

Elsewhere on the NS

Tax capital at the same rates as labour! It’s the open goal Labour refuses to commit to scoring. Why? Asks James Meadway.

Keir Starmer’s mediocre approval ratings won’t prevent a Labour victory, thinks Ben Walker, our election data guru.

Is it all over for the SNP? Chris Deerin reports. Note: if Labour and the SNP tie on 35 per cent in Scotland at the next election, which is no longer unthinkable, the SNP could end up with fewer than 20 Scottish seats, down from 45 today.

“Where is there in this country that’s by the sea, where it’s not polluted?” Emma Haslett has written an essential piece on the plight of Britain’s fishermen and women. Water companies are discharging raw sewage into British waters hundreds of times a day, with fines having no effect on their practices. When are we going to act?

“What GB News does well is tap into the same mix of rage, absurdity, weariness, titillation and camp that the tabloids did in their golden age. It’s the perfect broadcaster for anyone who’s furious that the Sun costs 70p now.” Clive Martin on GB News and the rise of what he calls the pantomime right on the channel.

This government doesn’t have a clue about grooming gangs, argues Nazir Afzal, the former CPS prosecutor.

Lamorna Ash explains why you should learn poetry off by heart.

Jeremy Cliffe interviews Graham Allison: “American politics is driving towards a provocation that China could not avoid.”

Here are the NS’s books of the year so far.

Audio long-read: Is the future of Christianity African?

Tomiwa Owolade asks how immigration is revitalising British churches. Listen to his audio long-read here.

There is a building in the south London borough of Lambeth that used to be a bingo hall. For decades, generations of men and women came here for pleasure and recreation, community and belonging. Now its grey walls are scoured with graffiti. This building is silent for most of the week, a picture of dereliction – except for Sundays. Then, between 10am and 12pm, a resurrection begins.

And with that…

This week I have had my head buried in books about the Conservative Party. (Being a journalist is glamorous isn’t it?) Take the longest view and a clear picture emerges, both of the party and the country it so often governs. Britain, roughly since the days of the Great Reform Act in 1832, has been a Tory Nation. Though they are rarely supported by more than a quarter of eligible voters, the Tories – through a mixture of guile, systemic advantages and sheer luck – more often than not end up running Britain.

One thing Tories are good for, other than winning, is a quote. Here’s Denis Thatcher, caught in conversation a few days after Tony Blair’s landslide in 1997: “We must get back to basic Conservative principles – but don’t ask me what they are.” Here’s David Cameron, after being asked why he ought to be prime minister: “Because I think I’d be rather good at it.” And here’s Arthur James Balfour who, in a tight field, may have been the most magnificently negligent of all Tory leaders: “I would sooner take advice from my valet than from a Conservative conference.”

Keir Starmer’s move to the centre right in the last 18 months suggests that even when the Tories are out of power (which they surely – surely? – will be in 2025), Labour is forced to govern on Conservative terms. My somewhat gloomy conclusion from all this is that Britain is a deeply conservative country, and probably always has been. It was JS Mill who wrote that “the English, of all ranks and class, are at bottom, in all their feelings, aristocrats”. I would expect, with Britain’s population greying and the dawn of what has been called “the age of scarcity”, that the Tories will slouch back into office around 2030. It’s what they do, and it’s usually what we want.

Thank you for reading. Don’t miss out – subscribe to the New Statesman and stay up to date with everything you need: from news and analysis to comment and criticism.

Whether you’re looking for a sharp blog or a finely written feature, the New Statesman has you covered. Have a good week, and catch you next Saturday.

To be Conservative or conservative - that is the question. Whether 'tis better for your mental health to suffer the spin and untruths of outrageous Tory governments, or to take action against this sea of troubles, and by opposing end them?

To be conservative, is to find some change uncomfortable and to be passively resisted - at its heart our nation does not mind change, but we hate being changed. That is why the current Conservative government has gone too far for conservative Britain. First Brexit, and a very bad one at that, then the traducing of parliament, followed by attacks on our civil liberties, the destruction of our economy, the strangling of our NHS, the collapse of our care system, the imposition of more poverty, the dumping of asylum seekers on our towns, the trashing of our rivers and beaches, not to mention the visible evidence of decline - potholes, empty shops, petty vandalism, unsocial behaviour, and litter everywhere.

The conservatives are slow to anger and action, but when they do move against the Conservative government it will be a moment of catharsis for the country.

We are a small c moderately socially conservative country, but with a predominantly right wing (rabidly so) press, owned by too many non doms. This gives the Conservative Party an in built advantage. The fact that our left/liberal parties don’t like it each other and split the vote in a first past the post voting system, gives the Tories an in built advantage.