The Saturday Read: Lasting legacy

Inside: Rochdale, Hoyle, Keir, 1974, Iraq, bluestockings, motherhood, and comedy.

Good morning. Welcome to the Saturday Read, the New Statesman’s weekly guide to the best writing on politics, culture, books, and ideas, sent to NS subscribers and registered readers. This is Harry, along with Will and George Monaghan.

This week Liz Truss, the once and future fool of British politics, appeared alongside Steve Bannon in America, spouting abstract conspiracy theories about the power of unnamed bureaucrats. “A new political era has begun. Or is it ending?” I wrote on the day she became PM in 2022, as we listened to her read off a set of utterly banal platitudes about “transforming Britain into an aspiration nation”. She never seemed likely to last and she had no redeeming qualities. I’d love to ignore her. But her spiral into quackery matters: it captures the Tory right’s disconcerting direction of travel.

Click to read online if this email cuts off. If you already subscribe to the NS, thank you. If you don’t yet and these pieces intrigue, perhaps you’d like to try a subscription.

1—“The plight of the Palestinians has made its way to the Pennines.”

Always read Anoosh, who wrote our cover feature this week on Rochdale, the upcoming by-election that captures what Britain is becoming. Travel with her across the constituency as she introduces you to its eclectic and universally undesirable mix of candidates. I love the way this piece ends. HL

On a blustery day in the Lancashire mill town of Rochdale, George Galloway rose to speak at a weekly lunch club of local women at Castlemere Community Centre, a handsome redbrick former Victorian school. He condemned the “carnage in Gaza”, mainstream politicians who were “ignoring” his audience and – with the same thundering intensity – the “state of the Exchange shopping centre”. The 70 or so women, mainly older British Muslims of Pakistani heritage, applauded from cabaret-style round tables bedecked in white tablecloths, as Galloway – who was expelled from the Labour Party in 2003 for his vocal opposition to the Iraq invasion – promised to bring a Primark to Rochdale. “Primark will be my lasting legacy!”

With its neo-Gothic town hall and faded civic grandeur, Rochdale is haunted by what it once was – a mighty industrial force in the high Victorian days of empire. The River Roch runs through the town and plastic bags float in waterways that once powered the cotton mills. Today, some abandoned mills are covered with “to let” signs, their chimneys mingling with tower blocks and minarets across the Pennine horizon.

2—“Bercow thrived on courting anger. Hoyle recoils from conflict.”

Freddie Hayward – who writes our daily political newsletter, Morning Call – takes us behind the scenes at Westminster during a week of high drama. Lindsay Hoyle, the Commons speaker, lost the confidence of more than a tenth of the House after being seen as having bowed to Labour on a question of parliamentary procedure, during a vote over the war in Gaza. HL

For 40 minutes on Wednesday afternoon, it was uncertain whether the Speaker of the House of Commons, Lindsay Hoyle, could hold out. Not in his job. But from being forced to return to his chair. The SNP’s pugilistic Westminster leader Stephen Flynn would not rest. He had just stood for the third time to demand to know where Hoyle was. Hoyle had gone against precedent – and his clerk’s advice – by selecting a Labour amendment to the SNP’s motion on an immediate ceasefire in Gaza. In doing so, he scuppered the SNP’s vote on the day it was supposed to control the parliamentary agenda.

It was 7.03pm before Hoyle returned. Here was the inattentive chef who had let the pans boil over. But he could not turn the temperature down. His defence was that Labour MPs needed to be able to vote on their amendment, and state to abusive and threatening constituents that they had voted for a ceasefire. Flynn was unappeased. “It will take significant convincing that your position is not now intolerable,” he growled.

3—“While everyone else made mistakes, he was careful.”

A former senior No 10 aide to David Cameron suggested to me this week that Keir Starmer would struggle in office. Starmer is not personally popular, and Labour are primarily heading back to power because of Tory error. That take may prove prescient, or it may age as badly as the comment a Labour supporter offered to me on the day of the 2010 election: “This is a good election to lose.” In a fine review of Tom Baldwin’s new biography, Andrew Marr considers the question of Starmer’s appeal and finds reason to like the man’s decency – and ruthlessness. HL

The problem for Starmer’s detractors is that it is impossible to imagine a journey for the Labour Party from 2019 to 2024, from the leftist wilderness to the edge of power, that could have been accomplished by stirring “Here I stand” speeches, and unchanging positions, always in the daylight.

Ed Miliband argues that “Keir is in nobody’s faction. I think he is bemused by the labels – he is nobody’s ‘-ite’,” but this does not mean he cannot be ruthless with people he sees as unhelpful in the party… The consequences can be severe for opponents. Michael Crick, the journalist who specialises in analysing candidatures, says the left has been “almost annihilated” in Labour selections under Starmer; out of some 200 candidates, perhaps only five left-wingers have been chosen.

4—“The tang of meth-enhanced custard remains an enchanting Proustian memory.”

This Colid Kidd essay on the 50th anniversary of the February 1974 election is full of things I didn’t know, including that the Norwegians managed to extract three times as much in tax per barrel of North Sea crude oil as the UK. They also set up a sovereign wealth fund that is today worth £231,000 for each of their citizens. Our North Sea inheritance was spent by Thatcher cutting taxes in the 1980s. Who wore it better? HL

There were reverberations then – and now – from the antipathy of recently independent African governments to the Asian populations that had arrived during the era of colonial rule. Indians in Kenya faced a hostile “Africanising” environment, and many, including Suella Braverman’s father, emigrated to the UK.

Things were immeasurably worse in Uganda. In August 1972 Uganda’s dictator, Idi Amin, who had seized power the year before in a military coup, expelled the country’s Asian population, giving them a mere 90 days to leave. In the course of 1972-73 around 40,000 Ugandan Asians – the majority of whom were British passport holders – came to the UK, including the parents of Priti Patel. An opportunistic Powell – still at that point a Tory MP – proclaimed that “people were rightly shocked at the prospect of 50,000 Asians from Uganda being added to our population”.

5—“Steve Coll is the Thucydides of American journalists: dry, cold, strictly factual and exhaustive.”

Robert D Kaplan reviews Steve Coll’s The Achilles Trap, a painstakingly detailed account of the relationship between the United States and Saddam Hussein’s Iraq. It’s a “devastating” story. WL

By the time George W Bush was elected president in 2000, Saddam and his regime were weaker than they had been in decades past. As Coll writes of Saddam: “Age, isolation, and a decade of family struggles had sapped some of his fire.” The great irony is that just as Iraq was becoming less of a threat the Washington elite was becoming more obsessed with the danger Iraq posed. The terrorist attacks of 11 September 2001, though not at all tied to Saddam, primed the Bush administration for focusing on him.

House views

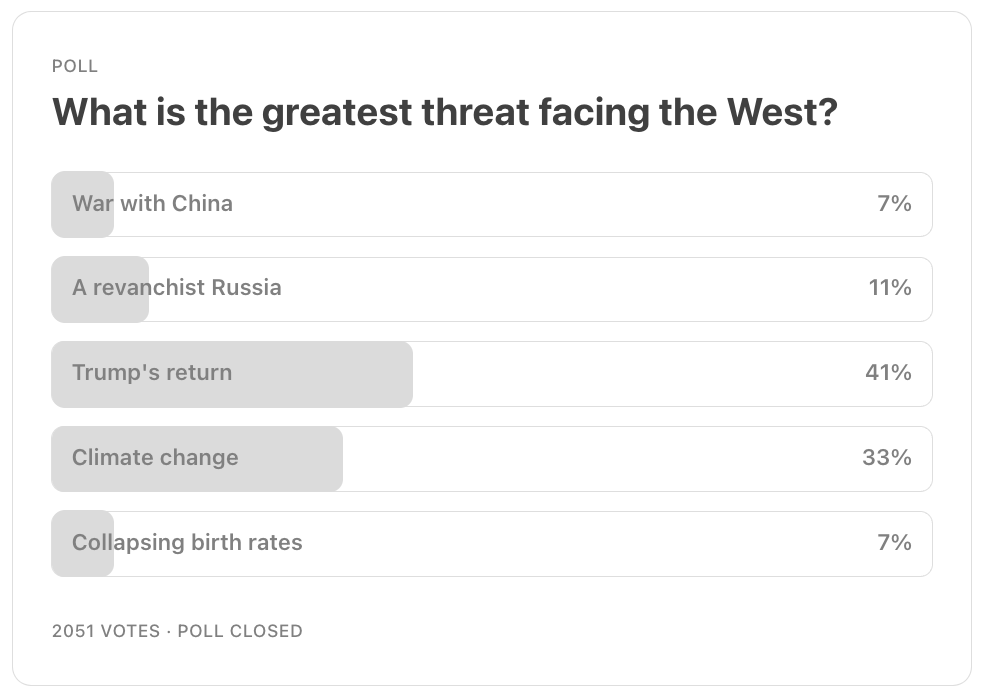

2,051 of you voted in last week’s poll on the greatest threat facing the West. Trump's return (41 per cent) edged out climate change (33 per cent) as your primary fear. A revanchist Russia (11 per cent), war with China, and collapsing birth rates (both 7 per cent) rated as secondary concerns.

Readers also wrote in: “Trump will come and go, but climate change will only come; it won't go away during the lifetime of anyone who is alive now.” “The return of Trump would affect all the others.” “Russia now. China, later.”

6—“The cardinal rules were to take learning seriously and to have fun with it.”

The bluestockings were 18th-century literary radicals who rebelled raucously against the idea that women could not be witty. Being a member of the movement sounds “both dazzling and exhausting”, Hannah Rose Woods writes, in reviewing Susannah Gibson’s new history of the movement. GM

It is, in every sense of the word, incredible that Thrale found time to read or write. Pregnant 15 times in 16 years, and violently ill with morning sickness, her twenties and thirties consisted of “holding my Head over a Bason 6 Months in the Year”. Only four of her children survived into adulthood. She stepped in to rescue her husband Henry’s brewing business when his disastrous venture with a charlatan scientist to transform rotten hops into “chemical beer” resulted in astronomical debts. She campaigned for his election to parliament. Any given day might have seen her tending to her dying child; her dying mother; her husband… after he had contracted another bout of venereal disease from one of his mistresses; and enduring the gloom and constant demands for attention of Dr Johnson, who had moved into their house in the expectation that she would tend to his eye infection. “Oh, what a life that is!” she recorded in her diary, “And how truly do I abhor it!”

7—“It’s completely devastating to a child’s life.”

Esther Ghey, the mother of the murdered teenager Brianna Ghey, has spoken to Sarah Dawood. One of the two killers, Scarlett Jenkinson, is thought to have been encouraged by watching murder and torture videos on the dark web. Where, asks Esther, are the protections for children online against destructive internet content? GM

Children have unfettered access to the most abhorrent content online, Ghey said, and it is impossible for parents to protect them. For this reason, she has empathy for the families of Jenkinson and Ratcliffe. “I have an understanding of what it’s like to be a parent to a teenager in this day and age. And with social media and the online world, you don’t really know what your child is up to. It’s just impossible to monitor them 24/7.”

8—“Time and time again, she prises open everyday scenes and extracts queasily beautiful images.”

Ellen has written a gorgeous review of Leslie Jamison’s new memoir, Splinters. Jamison admires her parents’ “shared ability to hold contradictory feelings”, and Ellen admires Jamison’s ability to do the same in her writing. The book “stacks up sensory, domestic details” and the review offers us a beguiling sample. This is how it should be done. Read it! GM

“In those early days, he was a man frying little disks of sausage on a hot plate in a Paris garret, asking me to marry him. Making me laugh so hard I slipped off our red couch,” she writes. Five years later, in a new home with her daughter, it’s: “Our nights were full of instant ramen and clementines. My fingers smelled like oranges all winter.”

9—“A display of courage I was certain I had never witnessed before: a man voluntarily delivering himself into the hands of his assassins.”

Why did Alexei Navalny return to Russia and to near certain death? What does his assassination tell us about Putin’s regime? Bruno Maçães explains how this murder, like the killing of Yevgeny Prigozhin last summer, demonstrates just how vulnerable Putin really is – a verdict with which Russian dissidents might disagree. WL

Navalny’s assassination is one more chapter in Russia’s descent into violence. Yet no state can live on violence alone. For Putin, the political problem is that the more he is forced to rely on violence as his only method of rule, the more violence has become the only metric by which he is judged. Has he become weak if a month passes without a high-profile assassination? Political history teaches us that no regime survives for long if it cannot appeal to a powerful idea. Putin is now engaged in a perilous experiment to prove that violence is enough. He appears ruthless at home, but two years ago this month that reputation pushed him to a war of conquest in Ukraine – he had to appear ruthless abroad – where victory remains doubtful and where defeat will dictate his destruction.

10—“In the current crop of late-night comedians’ jokeless taunting she might well have detected a strong echo of Trump’s own belittling laughter.”

What exactly is the status of laughter in democracies today, asks our critic Lee Siegel in this wide-ranging essay. This is an age of scolding, and cracking jokes carries roughly the same penalties as skipping through a field of landmines. Punchline at your peril. WL

Everyone knows that the frank speaking that is the heart of comedy is intrinsic to freedom. But we are living through a new epoch in which the right moment for such candour involves aligning it with intensely fragile selves – selves whose fragility (there’s no point in mocking, denouncing or lamenting this fragility; it is here to stay), which is the result of revolutionary forces, is creating a different politics and a different culture. Never mind what sort of laughter liberals or conservatives like. That lucubration itself sounds like the beginning of a joke. The democratic laughter of our time will have to nakedly acknowledge social and private pain at the same time as it makes its way through and around it.

Best of the Rest

Courtesy of George Monaghan this week.

Guardian: Barely 10 per cent of Europeans believe Ukraine can still defeat Russia.

Time: How Ukraine is really doing.

Times: Notting Hill capital gains tax exceeds that of the north’s biggest cities. I’m just an unfair tax system, standing in front of a population, telling it to stop complaining.

Ginevra Davis: How feminism ends.

Masha Gessen: The death of Navalny.

Dhruv Khullar: How Joe Biden could address the age issue.

Eliot A Cohen: Solzhenitsyn’s warning.

Alan Rusbridger: 7 October did not happen in a vacuum.

Tallest man and shortest woman become friends. Talk about a long distance relationship!

Monkey city – population: 30,000 – encounters planning objections. They’re going ape about this.

Elsewhere on the NS

Nigel Farage is (still) the man to watch if you want to understand the forces shaping British politics, argues John Gray. As in 2019, Farage once again has the power to sink the Conservative Party at the next general election. Will he use it?

“It is a bad time to be a British Jew.” Hannah Barnes examines the trends in the latest wave of incidents – most disturbingly, that one in five were perpetrated by children. David Feldman, meanwhile, points out the insidious stereotypes that have slipped into mainstream culture.

Britain matters again on the world stage, thinks Peter Ricketts, the former national security adviser and Foreign Office permanent secretary, thanks to the surprising return of David Cameron. It’s not what liberals or the left want to hear, but Ricketts lays out his case. (It also matters rather less since Brexit.)

Mormon “momfluencer” Ruby Franke has been arrested after starving her kids on the grounds that they were “evil and possessed”. Amelia Tait details the long dark relationship between fundamentalism and child abuse in America.

Jonn Elledge presents the depressingly persuasive case for a 2025 election. Ironically, it is now for the Tories that things can only get better.

Ben Walker, our pollster, examines whether George Galloway can win Rochdale.

David Gauke thinks the Lib Dems have a chance to soak up Tory votes. He’d know.

Donald Trump may have exhausted his capacity to shock, reckons Jill Filipovic, but his supporters have not exhausted their capacity for violence and abuse against his enemies.

Labour could “revolutionise the world of work”, thinks Daniel Chandler, so long as they don’t U-turn on their plans here too. Chandler backs policies in Germany, where employees get to choose at least a third of a company’s board members.

Tip of the week: The Way (BBC1)

Michael Sheen, James Graham and Adam Curtis have teamed up for a strange new TV drama, The Way, which hasn’t resonated greatly with viewers or critics. But Rachel Cooke thinks it’s well worth watching. Civil society breaks down in Port Talbot in a show that is “both hazily dreamlike and quite potently Welsh, a retro sensibility running right through it like a pattern in a pub carpet… It’s also quite thrillingly political, as if someone had lit a match beneath Newsnight… It’s provocative – audacious, even – in a way television rarely is now: not for the sake of it, but because it has an intellectual heart.” Let us know what you thought of the show if you saw it.

Talking of Rachel, I wouldn’t miss her review of Lauren Oyler’s new book of essays (Observer). She found little to like in this collection by a darling of the internet left: “While I understand its modishness perfectly well – its preoccupations could not be more Small Circulation Lit Mag, spring 2024, if they tried – it’s also rather cold and blank and small.”

Art corner

Michael has been to the Dulwich Picture Gallery’s new exhibition, “Soulscapes”, which he lightly skewers in the deftest of ways: “For a show that invites the viewer to look beyond the ‘cultural and socio-political formulations’ of Western landscape art, the majority of the works instead confirm the fact that, wherever it is sited and whatever form it takes, nature evokes a similar range of emotions in all artists, regardless of their roots.”

If today’s pieces intrigued, you could subscribe to the New Statesman. Stay up to date with everything you need: from news and analysis to comment, criticism and essays.

Whether you’re looking for a sharp blog or a finely written feature, the New Statesman has you covered. Have a good week, and catch you next Saturday.