The Saturday Read: Market decadence

Inside: The return, the Iliad, the G20, two interviews, and lessons from Latin America.

Good morning, and welcome to the Saturday Read, the New Statesman’s weekly guide to the best writing on ideas, politics, books and culture. This is Harry, along with Pippa. Will is tied up catching a marlin this week.

Who started this culture war? The Guardian’s music desk this week took a strong line against the pop singer Róisín Murphy, after it was discovered that Murphy had questioned the prescription of puberty blockers for children. The review, which set fire to Twitter and contained assertions contested by readers, revived a perennial debate: should you review the opinions of an artist when you review their work?

If today’s pieces intrigue, perhaps you’d like to try a trial subscription to the NS. Read three free articles after registering on our site. A digital subscription is only 95p a week. Let’s get to it.

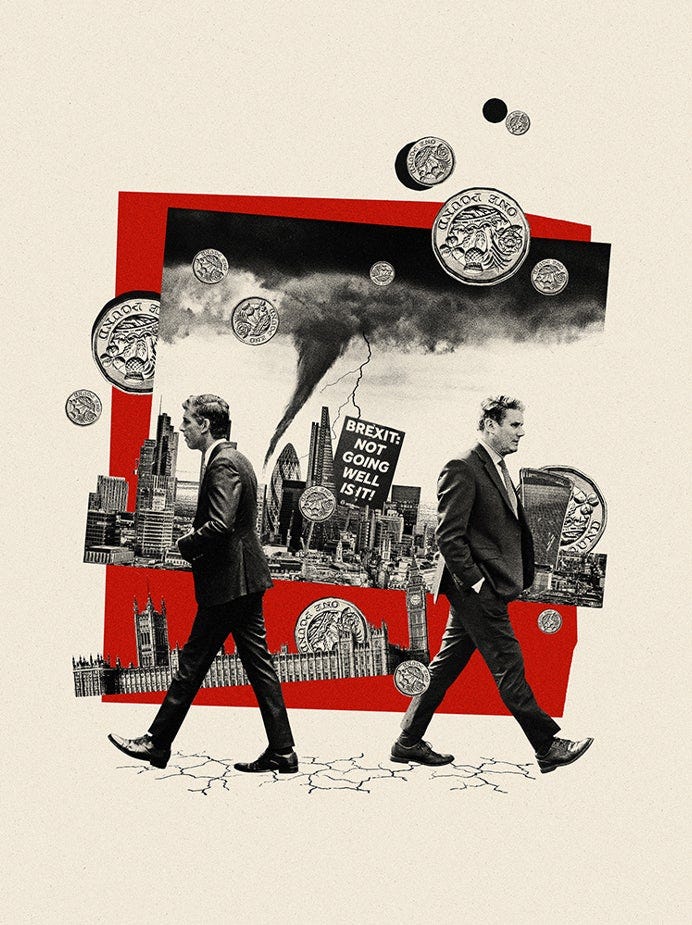

1—“The point of August is perspective – having the time and space to see the bigger picture hidden by the clattering Westminster treadmill.”

The great crack-up is coming, if it’s not already here, writes Andrew Marr in this week’s cover story. (Will Dunn has more on how some of Britain’s schools have come close to crumbling.) “The tough truth,” Andrew argues in his survey of the scene, “remains that we inhabit an economy too small to deliver the social goods British people expect, and with a terrible productivity record over the past two decades.” HL

The English schools crisis is a good example of the consequences of relative economic failure. That so many were constructed out of something that appears to be closely related to Aero chocolate bars is not particularly surprising: lots of technical and construction errors have occurred in recent history. What is noteworthy is that the problems were spotted early but dealing with it was endlessly put off, most recently by Sunak, until this autumn’s crisis.

Perhaps you might like to sign up to our weekday political newsletter:

2—“Until the Great Depression and the takeover of power by a military junta in 1976, Argentina was a first-world country and one of the richest.”

John Gray takes us to another era on the other side of the world to explain our present moment at home. An outsider candidate and market fundamentalist – Javier Milei, also known as “the Wig” – has taken the lead in Argentina’s presidential primaries, six weeks before the country votes. How did we get here? And what does Argentina’s political arc reveal about Britain? (NB: Sohrab Ahmari has reviewed John’s new book for us here.) HL

The old Peronist smiled when I asked what would be the next big change in world politics. Speaking in immaculate English, he replied: “The decadence of market power.” Near the end of the Nineties, it was a strikingly prescient observation. Comfortably seated beneath a vast portrait of the dictator’s wife, Eva, the exquisitely tailored survivor from another political era anticipated the deliquescence of the post-Cold War global market, which opinion formers throughout the West believed to be everlasting.

3—“Life, even for the hero, is short and vulnerable.”

There aren’t many people more qualified to write on gods and men than the former archbishop of Canterbury, Rowan Williams. He reads a new translation of Homer’s Iliad by Emily Wilson and finds a bleak depiction of human self-interest. PB

The fates of individuals are fixed and even the highest of the gods would be ill-advised to meddle with this. What is left? Making sure that honour and status are properly observed, that you have the right place reserved at feasts and the appropriate solemnities after death. That is why honour matters so intensely: there is nothing else to work for. Yet working for it as Achilles does is fraught with risk and constantly rips apart the ordinary well-being of the world.

Homer never argues or rebukes: but he diagnoses the sickness. The confusion between humanity and deity, the identification of self-interest with the eternal order of things, is the root of murderous and uncontrollable strife.

4—“At a certain point you realise it’s very funny.”

After years of being mistaken for the conspiracy theorist Naomi Wolf, the writer and activist Naomi Klein had had enough. She tells Sophie McBain how her fascination with her doppelganger led her into a mirror world of “alternate facts”. PB

Wolf was enjoying a surge in online popularity as a Covid denier who compared the vaccine roll-out to mass murder. On right-wing news outlets, she accused the global elite of using the pandemic to usher in mass surveillance. It was as if, Klein observed, she had lifted ideas from Klein’s 2007 book, The Shock Doctrine, “fed them in a bonkers blender and shared the thought-purée with Tucker Carlson”. Klein became curious, and then obsessed: how had this liberal feminist become a regular guest on Steve Bannon’s War Room podcast?

How to make IT sustainable

The IT industry has been a significant source of environmental damage, but is now transforming itself. It has responded to the need to develop better sustainable IT, from manufacturing to services to decommissioning. In partnership with Intel vPro.

5—“First it’s Ukraine, then it’s Poland. We are western Europe’s minefield.”

The Polish MEP and former foreign minister Radek Sikorski tells Katie Stallard what Putin’s war on Ukraine looks like from his side of the border, and why the destruction of Nord Stream was a good thing. PB

“Realism about Russia grows in proportion to the shrinking physical distance [between your countries],” Sikorski said. “If you are Portuguese, or Spanish, or Italian, then you have never had Russian soldiers in your country against your will, and you never will. Whereas we have had them looting and raping and imposing an alien political system on us, repeatedly, over 500 years.”

6—“It would be preposterous to suggest that India will dominate our century either militarily or economically.”

With India hosting the G20 this weekend, Pratinav Anil takes a look at the world’s potential “third power”. This piece will tell you a lot you might not know about the country – its political life, its geopolitical position, and its leader, Narendra Modi. HL

At the age of 72, Modi is rising. But is India? The middle class is smaller than you might think. Multinationals dream of Indian yuppies consuming their products, but only 84 million Indians (out of an estimated population of 1.4 billion) earn more than $10 a day. A third of the country’s workforce is made up of footloose labourers, casually employed on farms and construction sites far removed from their homes. A tenth are child labourers. The female labour participation rate stands at 22 per cent. The country’s wealth is no longer flowing outwards, to a distant empire, but rather upwards, to billionaires. At the G20 summit, Modi will no doubt remind his audience that India is the fifth-largest economy in the world. For most Indians, however, another statistic appears more relevant: in per capita terms, India ranks 139th.

7—“McDonald is presented as the standard bearer of a new, purified Sinn Féin.”

Finn McRedmond reviews The Long Game: Inside Sinn Féin, by Aoife Moore – a new book which attempts to track the strange evolution of Irish republicanism from murderous irredentism to party of government. HL

Sinn Féin is in psychological turmoil. It wants to be seen as a contemporary party fit for office, shorn of its violent history and no longer inextricably tied to the IRA. But it does not want to betray its legacy, namely those who fought and died for the republican cause. The party’s president, 54-year-old Mary Lou McDonald, has come to symbolise this bipolarity: she is a slick, well-educated politician with a Dublin accent and the manners of a Tory; she is also willing to defend the party’s militant record and commemorate the lives of the IRA. As Sinn Féin has emerged as the most popular and well-funded party north and south of the Irish border, the question lingers: what does it mean for Sinn Féin to absolve itself of its bloody past? And does it even want to?

8—“Hello everyone. Thank you for inviting me here.”

That’s Tom speaking, the AI that has solved climate change – will the prime minister take its lead? This is an inspired, Black Mirror-esque piece of speculative fiction, only Will Dunn is funnier than Charlie Brooker. PB

People moved with caution, as if the heat was an illness, which for some it was. Everywhere there was a smell of straining electrical components, hot plastic, damp shirts. On one side of the dais at the end of the hall, banks of monitors were being set up, while in its centre a lectern waited.

The people wanted an answer. A lot of people had wanted answers for a long time, of course, but until June it had all been something that happened in the Global South, or in the minds of scientists and doomsayers. The protesters were twats, easily ignored, and the more annoying they became, the easier it was to deride them or lock them up. And now they were gone, the roads were clear, but the tarmac was melting and if you didn’t have reliable air-con you’d end up like those poor people on the M5, burning their hands on the gleaming bonnets as they staggered for the ambulances.

9—“Success in the global technology game was a factor of a country’s power and sovereignty, not of its inventiveness and openness to new ideas.”

Evgeny Morozov turns to the “other 9/11” – the coup that toppled Salvador Allende’s Chilean government in 1973 (an event Gabriel García Márquez covered at the time in the NS). That coup thwarted democracy in Chile. It also thwarted plans for an “International Technology Fund” in the mould of (but superior to) the IMF. HL

In the new global system envisioned by Letelier and Allende, each nation, including those currently referred to as the Global South, would eventually be capable of developing their own unique industrial – and technological – stack. This strategy would prevent them from having to rent various technologies – think of cloud computing or artificial intelligence today – from the multinationals, thereby halting the cycle of their own technological and economic dependency.

But this vision was never realised. Merely six weeks after the summit in Lima, on 11 September 1973, Allende’s government was toppled in a military coup that ushered in General Augusto Pinochet’s brutal dictatorship. Orlando Letelier spent the next 12 months in brutal concentration camps, alongside many other prominent members of Allende’s administration.

Will’s Best of the Rest

WSJ: The Middle East is a global ATM. And yet they still won’t give me money to cover my rent.

Telegraph: Starmer’s “band of Blairites” reshuffle. Let’s hope they have no plans to invade Iraq this time.

Vulture: How Zadie Smith lost her teeth.

Times: Mental health “higher priority than climate” for the under-40s.

Laura Kuenssberg: My ratings are actually good. God loves a trier.

Yiyun Li: Montaigne is better than yoga.

Tyler Cowen: AI hype is over, but the revolution continues.

Joe Garcia: Listening to Taylor Swift in prison. Imagine being on Death Row and only having her for company.

Christopher Caldwell: Did the US really abolish affirmative action?

Starmer rolling around in hay. About as convincing as the time Gordon Brown claimed to be an Arctic Monkeys fan.

Elsewhere on the NS

“This has been a week of ghosts of politics past. It found its best expression in an unlikely place – in the grand temple of Joseph Chamberlain; the Victorian corridors of Birmingham City Council.” Lewis Goodall looks at the council of his home city and its lurch toward bankruptcy.

In one of the Peak District’s most beautiful valleys, a battle over who secretly runs the world rages. Freddie Hayward reports.

Throughout his career, Britain’s wartime prime minister studied how other leaders – Roosevelt, Attlee, Stalin and Gandhi – exercised power. David Reynolds on Churchill.

Hannah Rose Woods says the history wars aren’t a modern phenomenon: the British empire has always been contested.

Erica Wagner reviews the Irish author Anne Enright’s new novel of love and trauma, The Wren, The Wren.

A bucolic camping weekend in Kent was interrupted for Pippa Bailey by a run-in with a group of traveller children and a lost dog.

Peter Williams finds David Stubbs’s history of British comedy disappointingly hackneyed.

Kim Darroch has filed this week’s Diary. It includes an amusing insight into diplomacy at a G20 summit in London, featuring Nicolas Sarkozy and an unplugged sound system.

Drill, writes Josiah Gogarty, is the UK’s real cultural export. Global Britain? This is it.

How to get into: Ballet

Each week we ask someone to recommend three books as a way into a subject. This week we turned to Zuzanna Lachendro, who assists the editorial team at the NS.

Apollo’s Angels: A History of Ballet by Jennifer Homans (2010): The New Yorker dance critic Jennifer Homans presents an immersive historical survey of the globally revered art form, beginning with its origins in 18th-century France. Homans links the developments in technique to great political and intellectual movements over the centuries and draws on the influences of French classicism, romanticism, Bolshevism and the Cold War. Today ballet is in a crisis, Homans fears. The brilliant minds behind it are “dead and gone”.

A Life in Motion: An Unlikely Ballerina by Misty Copeland (2014): In 2015, Misty Copeland became the first African-American woman to perform as a principal dancer with the prestigious American Ballet Theatre. Her memoir offers a unique perspective on the life of a ballerina breaking into the form’s “white and wealthy world”.

Bolshoi Confidential: Secrets of the Russian Ballet from the Rule of the Tsars to Today by Simon Morrison (2016): In Bolshoi Confidential, Simon Morrison, the musicologist, traces the nuanced history of one of Russia’s most prestigious institutions – an acid attack in 2013 partially blinded its artistic director – and how its power has always been twinned with Russia’s neo-imperial ambitions.

Thank you for reading. Don’t miss out – subscribe to the New Statesman and stay up to date with everything you need: from news and analysis to comment and criticism.

Whether you’re looking for a sharp blog or a finely written feature, the New Statesman has you covered. Have a good week, and catch you next Saturday.

Thanks to Chris Bourn and Pippa Bailey.

A reliable weekend delight. Thanks.