The Saturday Read: Meltdown

Inside: Liberation day, the British curriculum, Picasso’s muses, lawfare in France, the Daily Mail, Gary Stevenson’s economic vision and the Europeans who built Britain.

Good morning. Welcome to the Saturday Read, the best of the New Statesman, in print and online this week. This is Finn with Nicholas and George.

At the end of January I titled an edition of the Saturday Read “Move fast, break things” – in reference to Mark Zuckerberg’s 2012 coinage, and an attempt to reckon with the energy of the newly inaugurated Trump administration. It feels quaint to think about now: that was before Elon Musk took a sledgehammer to American bureaucracy, before the US retreated as Europe’s security guarantor, and long before “liberation day” lit a match under the global economic system.

The world may be on the brink of a full-scale trade war after Donald Trump announced steep tariffs on imports to the US. Yesterday, China accused the US of “unilateral bullying” and retaliated with its own 34 per cent tariffs. Meanwhile, Keir Starmer and the EU are holding fire, cautiously optimistic that Trump can be convinced to soften measures. But for now, the markets are in turmoil: on Friday the FTSE 100 suffered its worst day since March 2020.

Will this end up a mere macroeconomic blip or a historic turning point? Will Dunn investigates below. And our politics team across Washington DC and London will help you navigate the coming weeks and months. As ever, thanks for reading and have a great weekend.

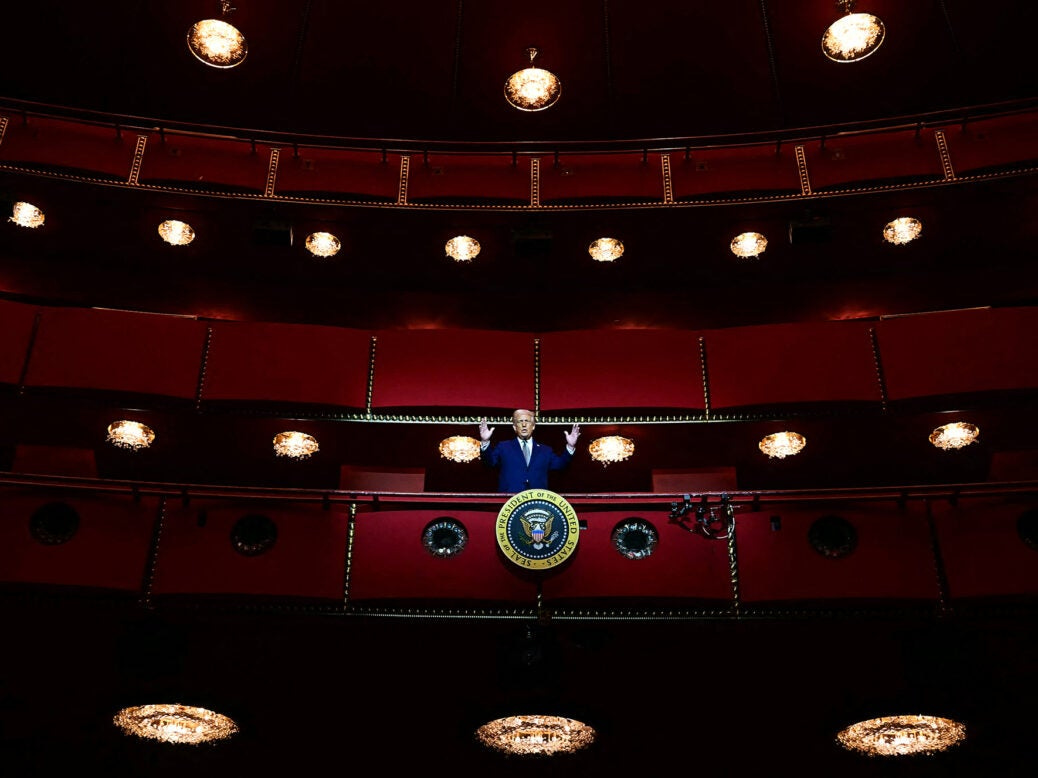

1—“Assert dominance”

And here is Will on it all. Yes, it’s the economy (stupid!). But it’s also about restructuring the world to be even more accommodating of America’s corporate and political caprice. FMcR

Consider also this line from the White House fact sheet accompanying Trump’s announcement: “Access to the American market is a privilege, not a right.” US officials recently confirmed this when they wrote to European businesses demanding they comply with Trump’s executive order banning diversity programmes if they supply goods or services to the US government. These letters claimed that Trump’s policy “applies to all suppliers and service providers for the US government, regardless of their nationality or the country in which they operate”. It may be that America is following China in using the power of its consumer market to export its politics. If you operate an airline with flights to the US, for example, there might come a time when you have to think about how your company’s maps describe Greenland.

2—“The soul of English education”

In some moment of adolescent pique, we’ve all asked the question: “What is school for?” For this week’s cover story, Pippa steps forward to answer in a totalising survey, taking in the history of British schooling, and the purpose of education itself. NH

Should school prepare children to take an economically productive place in the workforce, or to thrive in the academic rigour of university? Does it have a more holistic purpose, to create well-rounded, emotionally mature members of society? And is it possible to design a curriculum that works for children who will go on to be doctors and lawyers and those who will be bus drivers and mechanics? It is these questions of purpose, as much as any arguments over diversity or decolonisation… with which Labour and its curriculum review must now do battle.

3—“Small cracks”

It felt odd to see Maga lose, but it happened in Wisconsin this week. Elon Musk poured $25m into the Republican-backed candidate for Wisconsin’s supreme court, to no avail. Freddie explains how it happened. GM

This might have seemed like an obscure state judicial race in the first place, but Musk got involved because the stakes were so high: the Wisconsin Supreme Court could order congressional districts to be rejigged, which could help the Democrats win back the House of Representatives at the mid-term elections next year. Even if Trump doesn’t sour on Musk, expect this result to energise Musk’s dissenters over on the Hill.

4—“He found his next muse…”

Pity the embattled Picasso fan: “Yes, terrible man, I know… great paintings though, but yes, what a jerk.” To love art that emerges from a malign source requires constant rhetorical gymnastics. And this wonderful essay by Sue Prideaux – on his mistreated lovers – won’t make the exercise any easier. FMcR

Two of the six killed themselves. Picasso was a coercive controller well before the term was coined; not untypical of his time. His own particular repeating pattern was to be attracted to strong women, compel them into swearing extreme oaths to love him forever – “…and whoever breaks this contract will be sentenced to death…” ran a declaration he signed in 1918 – then, when they got ill or pregnant or he found a new muse, to cast them off like used gloves, as novelists of the time were fond of writing. The unasked, and unanswerable, question resounding through the book’s harrowing narrative is: how much of his greatness would have been lost had he been nicer?

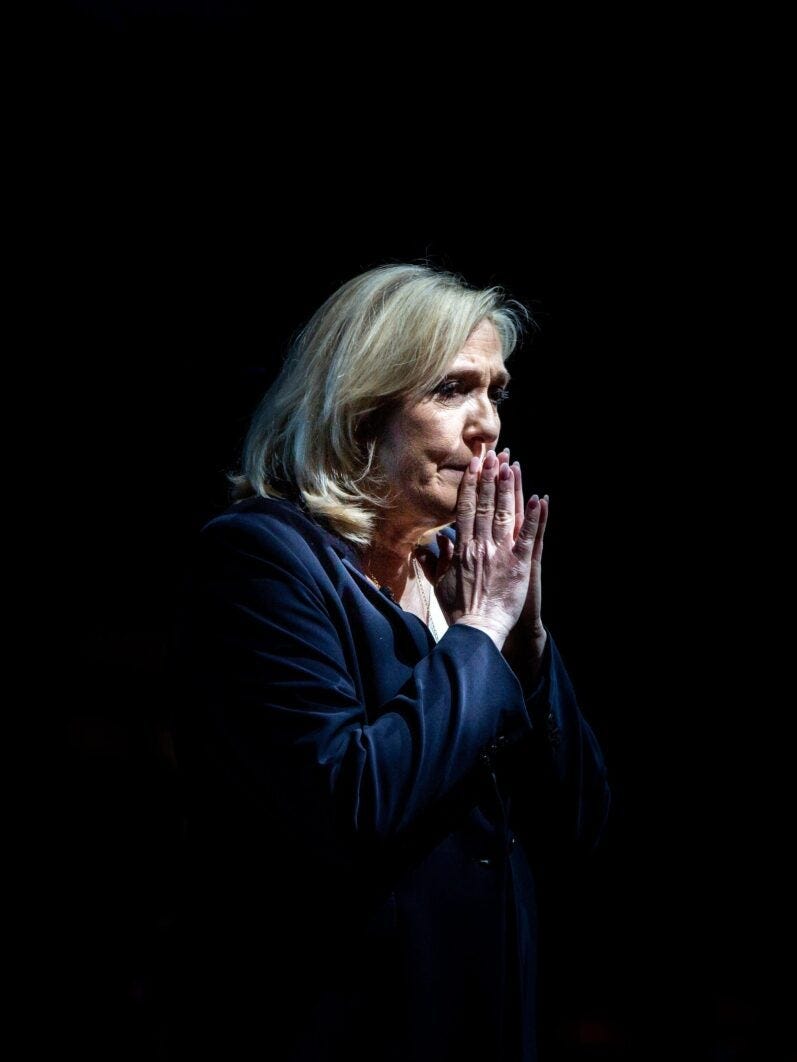

5—“Fired the starting gun”

In the whirlpool of tariff week, try not to forget the news from France: Marine Le Pen of National Rally, the frontrunner candidate for the presidency, has been disqualified from 2027’s election. (Though I suspect it is unlikely her politics will be defeated by lawfare.) David Broder, an expert on the European right, has the details. FMcR

Jordan Bardella, the 29-year-old president of the National Rally, likewise claimed that French people’s choice was being denied. “Today, it is not only Marine Le Pen who is being unjustly sentenced: French democracy is being executed.” The party’s preaching against the “corrupt political class” and its scandals has vanished, in favour of the claim that the legal process is politically weaponised. Bardella, the party’s candidate for prime minister last year, may run in Le Pen’s place in 2027.

In a way, it’s a chance for him to forge his own reputation independent of Le Pen – though Le Pen’s conviction will surely hang over the entire presidential campaign.

To enjoy our latest analysis of politics, news and events, in addition to world-class literary and cultural reviews, click here to subscribe to the New Statesman. You'll enjoy all of the New Statesman's online content, ad-free podcasts and invitations to NS events.

Why adversity creates opportunity:

Discovering the best dividend payers means digging deep, biding your time and choosing your moment to buy the best, writes Ross Mathison, deputy manager of The Scottish American Investment Company (SAINTS). Capital at risk and income not guaranteed. Read now.

6—“The Mail folded under his arm”

When the Daily Mail festooned its front page with Starmer praise, many asked what on Earth was going on. Nicholas answers: the plan. Labour’s chief of staff Morgan McSweeney has long been wooing “the bloke you see in the pub”. GM

With the ascendancy of McSweeney’s Labour Party, we are seeing this Labour tradition in its 21st-century form. This is the age of Daily Mail socialism. And its enemies are as easily personified as its Middle England constituents. McSweeney again: “Why should Labour be the party of the judges? Why should we be the party of the BBC?” For the parts of the left that turned Brenda Hale into an anti-Brexit hero, for the public-sector workers who reliably vote Labour, such talk will seem heretical.

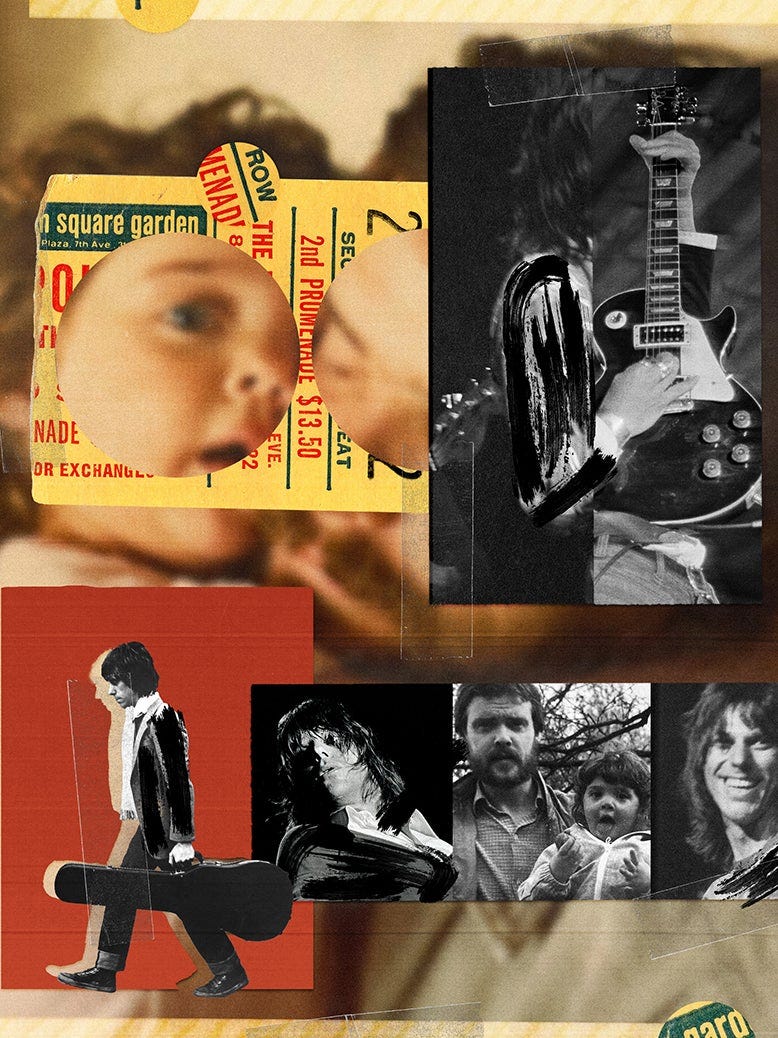

7—”Direct line to the soul”

Kate Mossman’s music profiles have long cried out for collection, and to mark the publication of Men of a Certain Age (available here), this week she wrote a very moving first-person piece on her “quadrophonic” listening habit of hearing music through her father’s ears. NH

Pop music is often thought to be a rehearsal for adult experience – a space in which teenagers explore the complicated shades of romantic feeling they haven’t yet met in the world. I think it can be something else, though – a form of regressive longing, taking you back to your earliest feelings of love. It is part of an adolescent’s job to regress like this – to seek some rejuvenating return to childhood feelings amid all the new experience.

8—“Intellectual refugees”

German émigrés fleeing fascism transformed British culture to an extent most us cannot comprehend. But if you have walked past London’s Trellick Tower or picked up a brown Penguin paperback, you felt their influence. Nikhil Krishnan investigates the Europeans who built this country. FMcR

When the first intellectual refugees arrived in Britain, the country they entered was “irrational but smooth and pleasant… insular and monocultural; cold and emotionless”, Hatherley writes. It was “a culturally conservative enclave distant in mind from continental Europe and implacably hostile to avant-garde ideas”. Even the artistic elites who had an interest in modernism were Francophiles, and saw little of worth in the culture of Weimar Germany. A New Statesman critic, revolted by the “Twentieth Century German Art” exhibition that had been organised by émigrés to counter Nazi propaganda, wrote that the Führer’s dislike of these paintings “must be one of the best things about Hitler”.

9—“Frank, optimistic, demotic, sincere”

Why does the trader-cum-activist Gary Stevenson provoke such serious indignation? Because, James Meadway argues, of his unstinting and over-straightforward rhetorical campaign. NH

Gary is probably the foremost communicator of economic ideas we have in this country. Still eloquent, his combination of experience and background currently gives him a Teflon quality that drives his opponents apoplectic. The crypto hucksters and the von Mises fanboys hate him, truly hate him for this: he’s marched into their safe space and bagsied it, and their audience, for himself.

10—“A conspiracy of globalist schemers”

Drawing on the research for his new book, Ghosts of Iron Mountain, Phil Tinline traces one of the America’s greatest hoaxes, and follows the lead to current anxieties about the “deep state”, Elon Musk’s Doge and his state-scything chainsaw. NH

Even as the fortunes of the real state soured, the notion of the sinister power elite soared. The Watergate scandal broke President Nixon – but it also fostered the idea that large, nefarious forces were at work. Congressional inquiries exposed the illegal schemes of the secret state: the FBI’s attempts to destabilise the radical left, the CIA’s horrifying efforts to master “brainwashing”. These revelations humiliated the agencies involved, yet confirmed their sinister power. No wonder that in 1980, the proportion of Americans who told pollsters they thought government was “run for the benefit of a few big interests” hit 70 per cent.

George’s Best of the Rest

Thomas L Friedman: The future has left America

Daniel Finkelstein: Austerity Reeves is at one with Osborne

Freya India: The right has forgotten feeling

Fabian Scheidler: Preventing peace

Seamus Perry: William Blake’s sea monsters

Christopher Gage: The art of doing nothing

Amelia Tait: Correcting everything I’ve ever said

Island inhabited only by penguins also gets tariffed. They’ve had it too good for too long.

And with that…

Whenever I rendezvous in Notting Hill, I keep my eye out: those stuccoed crescents are some of our nation’s most desirable streets, bringing together fame, cheekbones, and capital-gains. Until this week my gawping had been largely disappointed, its sole fruit being a view of Jamie Laing, thick in Lycra, unlocking his house after an early-morning run.

However, on Wednesday morning, I struck a very different carat of celebrity. Sat in one of the booths of an organic and expensive coffee shop was the former heroin addict, semi-aristocrat and novelist Edward St Aubyn, author of the Patrick Melrose series. I regard St Aubyn among our greatest living writers and, while not quite reclusive, he’s not exactly a chat show regular. This encounter therefore represented an extraordinary stroke of fortune. But more than that, it was something of a cosmic coincidence: I’m currently reading and rereading St Aubyn for a piece I’m looking forward to sharing with you all soon.

Given his reputation for satirical cruelty, in his writing and reportedly towards strangers, my approach was nervous. But he was a picture of generosity, signing “Teddy” on the trembling copy of On the Edge I offered him. And, he provided a few pointers regarding his new novel, Parallel Lines. St Aubyn is a laureate of irony, “that deep-down need to mean two things at once, to be in two places at once, not to be there for the catastrophe of a fixed meaning”. He has called that “the hardest addiction of all”. He would know, and I largely agree. But for exactly that reason it was pleasant to experience an undiluted, unironic feeling of literary awe.

The New Statesman is home to the finest writing on politics, culture and ideas. To stay up to date, subscribe using the link above.

— Finn, Nicholas and George.

Will Dunn’s piece struck a nerve. “Access to the American market is a privilege, not a right” is more than policy—it’s imperial logic rebranded for the neoliberal age. As China mirrors that stance, we’re not witnessing the rise of multipolarity—we’re witnessing the gamification of global power. No wonder the FTSE wobbled. Markets hate narrative disruption.

Seems to me "trust" is the one thing you can't dial into spreadsheets, price into markets etc...

because there's no way Trump can regain it...

https://justhinkin.substack.com/p/losing-hand?r=3cs2wr