The Saturday Read: Move fast, break things

Inside: Trump’s inauguration, Bob Dylan, Gaza, 100 years of Gatsby, Thomas Piketty meets Michael Sandel, the musicians of Auschwitz, and a poem by Michael Longley.

Good morning. Welcome to the Saturday Read, the New Statesman’s guide to politics, culture, books and ideas. This is Finn with Nicholas and George.

Donald Trump was inaugurated as the 47th President of the United States on Monday, flanked by members of the tech-bro establishment – Zuckerberg, Musk and Bezos. All three in some form have undergone a political evolution, but none more so than Meta’s CEO, Zuckerberg. He was once an arch-liberal and a champion of coastal America’s progressive pieties. Now he is telling Joe Rogan that it’s time to restore masculine values to the workplace, and loosening his platforms’ restrictions on speech.

But perhaps Trump and the entrepreneur were never that different. In 2012 Zuckerberg coined the maxim of Silicon Valley’s dreams: “move fast and break things”. The new president – never one to be paralysed by indecision – might be Zuckerberg’s motto made incarnate. Trump started signing executive orders before even returning to the White House on Monday. He has declared a national emergency at the southern border and withdrawn from the Paris climate accords and the World Health Organisation. On the same day he rescinded 78 of Joe Biden’s executive orders, too.

In our diary column this week – “An abomination of an inauguration” – Tina Brown laments the Capitol dais groaning under “the whole trashy crew”; “The visuals alone” she says “aroused in me a technicolour replay of political agita.”

Meanwhile, I am delighted to read the first in a new series of columns by our former editor-in-chief Jason Cowley, who will be writing weekly in the NS. Jason spent some time last year with David Lammy in Washington, working out how Labour would handle a second Trump administration. Now he flips the script, writing on Team Trump’s true feelings about Labour. It includes some wisdom from the “maverick” Labour peer Maurice Glasman: Maga thinks “the EU is a progressive death hole”. Well, then.

Below there are ten of our favourite pieces from across the magazine and website this week. To sign us off, a poem by Michael Longley. As ever, thanks for reading and have a great weekend.

1—“Legitimate ideologies”

During Trump’s inaugural address, Joe Biden and Kamala Harris sat on the side in silence, a chastening symbol of the humiliation of the Democrats. Thomas Piketty and Michael Sandel discuss how the left paved the way for right populism. NH

The taxpayer bailout of Wall Street cast a shadow over Obama’s presidency. It dashed the hopes for a revival of progressive or social democratic politics that his candidacy had inspired. And it generated two currents of protest: on the left, the Occupy movement, followed by the surprisingly successful candidacy of Bernie Sanders in 2016 against Hillary Clinton; on the right, the Tea Party movement, and the election of Donald Trump. Both of these strands grew from the anger and outrage and sense of injustice at the bailout and the building back up of Wall Street, without holding anyone to account. So in a way, the progressive, mainstream centre-left politicians who governed in the aftermath of Reagan and Thatcher laid the groundwork for the right-wing version of populism

2—“Paralysis, decay, denial, complacency”

Unusually aggressive weather patterns caused Los Angeles to burn for days in the middle of winter. But it was a long-fomenting combination of climate change, budget-slashing and general urban neglect that turned the region into a tinderbox, Richard Seymour writes. FMcR

Also at stake here is a defunct model of fire management. Lately, the right-wing press has credited Trump with having warned Governor Newsom about the wildfire danger. He claimed in 2019 that he told Newsom “from the first day we met that he must ‘clean’ his forest floors regardless of what his bosses, the environmentalists, DEMAND of him”. He also issued an executive order to increase logging on the grounds that this would curb wildfires in overgrown and fuel-dense forests. In fact, logging and “cleaning” the forest floors removes a source of moisture that retards flames. The evidence is that protected forests experience much less severe fires. As fire management expert Stephen J Pyne has been arguing for decades, suppression is bad management. It derives from an inappropriate importation by colonists of European fire practices, and it makes wildfires worse. California’s chapparal biome is adapted for fire: it burns, because it is meant to burn. It is human action, above all climate change, logging, real estate sprawl and dysfunctional public infrastructure that makes it more deadly than it need be.

3—“More durable than it appears”

To the question of the week – whether Musk intended that gesture – Ross Barkan has a controversial answer: it doesn’t matter. America is too big, wild and differentiated for fascism ever to take hold. GM

Those who speak of American fascism tend to do so from the airy citadels of media and academia. They barely seem to understand how the US functions. Consider public education. Any American fascist worth his bright red tie would be able to subdue the schools and begin to teach MAGAdemics, or at least get all those pesky liberal books banned – all of them, because fascism doesn’t demand anything less. In the US, there are nearly 14,000 separate public school districts with more than 94,000 elected board members. Some of the larger counties, like the battleground of Loudoun in Virginia, have a single board. Others are carved up into so many segregated duchies that consensus can never be achieved. On New York’s Long Island, among just two counties, there are 125 public school districts. There is no such thing as a centralised educational system in America. The US’s educational sprawl is Hapsburgian, with no single monarch able to dictate its direction for very long.

4—“Much-coveted metal”

A mine, an autocratic ruler, diplomatic feuding and hundreds of innocents caught in the middle? It sounds like a Conrad novel, but, courtesy of Francisco Garcia, it’s the true story of a Serbian lithium mine, a battleground for superpowers competing to fuel the energy transition. NH

Western coverage often portrays Serbia under Vučić as merely a Russian vassal state, but the reality is more complex. Vučić – a hard-right nationalist and arch political operator who served in various senior roles under the brutal Slobodan Milošević in the 1990s – has dominated Serbian politics since his election in 2012. Corruption is commonplace and the domestic press is tilted overwhelmingly towards the administration. Deep links between government and organised crime are well established. The Hungarian politician and sociologist Bálint Magyar has labelled Serbia a “post-communist mafia state”, along with his home nation and several others in the region. Serbian openness to foreign investment – Chinese, Russian, Western – is accompanied by brutal gutting of workers’ protections and a collapsing middle class. If international capital increasingly views Serbia as a land of opportunity, ordinary citizens have yet to feel the benefits. Mining is already a significant – and deeply controversial – plank of the Serbian economy.

5—“Even in hell, there was music”

At Auschwitz, where more than one million Jews were murdered, 15 orchestras operated. The Last Musician of Auschwitz tells their stories. Hannah Barnes found this new documentary extraordinary and haunting. GM

I am haunted by the story of Ilse Weber – the Czech Jewish songwriter – and how she turned to music in her worst moments. As pro-Nazi sentiment rose in late-1930s Czechoslovakia, Weber sent away her eldest son, Hanuš, to escape persecution; he became one of 669 children saved by the Kindertransport. In late 1944 the children at the Theresienstadt ghetto – including Weber’s youngest son, Tommy – were summoned to Auschwitz. Weber refused to let them die alone, so she chose to accompany them. At Theresienstadt, she had worked in the children’s hospital. While forbidden to provide medicine, Weber would sing lullabies to provide comfort instead. Later, at the entrance to the Auschwitz gas chamber, a guard advised Weber to gather the children, sit together on the floor and sing. It would reduce their fear, he said – and singing would help them inhale the gas faster, so they would die more quickly. I cannot get the image out of my mind.

To enjoy our latest analysis of politics, news and events, in addition to world-class literary and cultural reviews, click here to subscribe to the New Statesman. You'll enjoy all of the New Statesman's online content, ad-free podcasts and invitations to NS events.

Watching the new Bob Dylan biopic, A Complete Unknown, I was disappointed to find that it cuts off just as things got really crazy for Dylan. The film ends in 1965, with Dylan’s great electric turn. But 1965-66, before a mysterious summer motorcycle accident, always struck me as Dylan’s true apex. That was when everything started happening at once: globe-bestriding fame and recognition; a relentless touring schedule run on fumes and amphetamines; all while a stream of culture-defining verse poured from his head.

My favourite of the songs Dylan produced around this time is “It’s Alright, Ma (I’m Only Bleeding)”. It gets a walk-on in A Complete Unknown – Dylan wakes up a snoozing Joan Baez in their hotel room as he wrestles with the first few verses, essentially to crowbar one of Dylan’s best-known lines (“He not busy being born is busy dying”) into the movie. But the rest of the song is a masterpiece of flashing, associative imagery: “Darkness at the break of noon/Shadows even the silver spoon,” it opens, and follows in free-flowing, aphoristic fashion (“Money doesn’t talk, it swears”). At moments like this, Dylan enters the ranks of the greatest postwar poets. These lines will last long after he finally unplugs his electric. NH

6—“First as tragedy, second as reprimand”

Robert D Kaplan’s new book, Wasteland: A World in Permanent Crisis has an interesting premise: we should think of the global order through the analogy of a single state (a “geopolitical Weimar”, perhaps). Bruno Maçães reviews this unusual argument, and finds Kaplan’s instincts too fogeyish for the times. FMcR

I happened to be reading Waste Land as I was rereading The Man without Qualities, Robert Musil’s novel on the dissolution of the Austro-Hungarian monarchy. At times Kaplan’s voice became that of the imperial officials or respected members of the Viennese bourgeoise that, in Musil’s pages, haughtily proclaim that it is all very well to dream of a better world, but no one should actually try to bring it about. Kaplan should know that such words are almost always vacuous. If a political order leaves more people outside its orbit than those who are content to remain within it, there is little use for this paternalistic advice. The existing global order is now so tenuous and so limited in its reach that refusing to think of what will come next betrays nothing but a failure of imagination.

7—“Implicit remarks”

Deep breaths. We’re talking about Brexit again. David Gauke, former secretary of state for justice and now New Statesman columnist, was among the slew of Tory Brexit rebels in 2019. Now he makes a convincing case nearly six years on: the European question is far from resolved. FMcR

On the merits of her case, speaking as a member of the cabinet when our departure from the EU was triggered, she has a point that it would have been better to have come up with a plan for Brexit beforehand. But, in practice, delaying our departure would have been politically impossible given the views of Brexiteer MPs. Delay would quickly have been seen as betrayal. And even if we had taken more time, the same trade-offs and challenges would have existed. To put it another way, we would still have ended up with a situation that would have made it harder to grow the economy than if we had remained. It is a myth to believe that there was ever a brilliant Brexit growth plan out there. This point will be challenged by Leave supporters. But, given her remarks, the onus is now on Badenoch to devise her own plan to make a success of Brexit.

8—“Shaky political horizons”

The guns are (mostly) silent in Gaza, and the ceasefire appears to be holding. But, after 471 days of fighting, what is the long-term future of the Strip and its population? Yair Wallach unpicks the forces at play: a hard-right Israeli administration, the regrouping of Hamas, and a displaced people. NH

The sight of Hamas militiamen openly roaming in Gaza makes a mockery of Netanyahu’s “total victory”. Yet the re-emergence was inevitable given the lack of any alternative plan. The emergence of a legitimate Palestinian governing body in Gaza could prompt calls to establish a Palestinian state in Gaza and the West Bank. This is anathema for Netanyahu and his government. Instead, we may be seeing a revival of his and Hamas’s belligerent pact. The group’s survival provides Netanyahu with an excuse to extend the war indefinitely, as he fears he would be forced out once it is over. It is widely assumed he will try to sabotage the negotiations over the ceasefire’s next phase and resume the fighting.

9—“Literary synaesthesia”

F Scott Fitzgerald dreamt of writing “something extraordinary and beautiful”. One hundred years after The Great Gatsby, the world agrees that he succeeded. But the book is easily misunderstood, warns Sarah Churchwell. Don’t call it realism; Fitzgerald does not just describe reality – he enlarges it. GM

These deadening clichés distort our view of Gatsby in important ways. They keep us from registering how rich and strange and alien its world is: the New York of Gatsby lures us in because it is a surreal and surprising city, without a trite yellow cab in sight – but a lavender one is waiting for those who care to notice. All these carefully chosen details also suggest a world beyond the merely mimetic – what John Updike once called the ability of language to be “worked into a supernatural, supermimetic bliss”. The reason everyone who reads Gatsby wants to join the fun has far less to do with our ideas of what a jazz-ge party looked like than with the vital strangeness of Fitzgerald’s writing. The lavender taxi is hyper-realistic, but it is also surrealistic, capturing the phantasmagorical qualities of Gatsby’s New York.

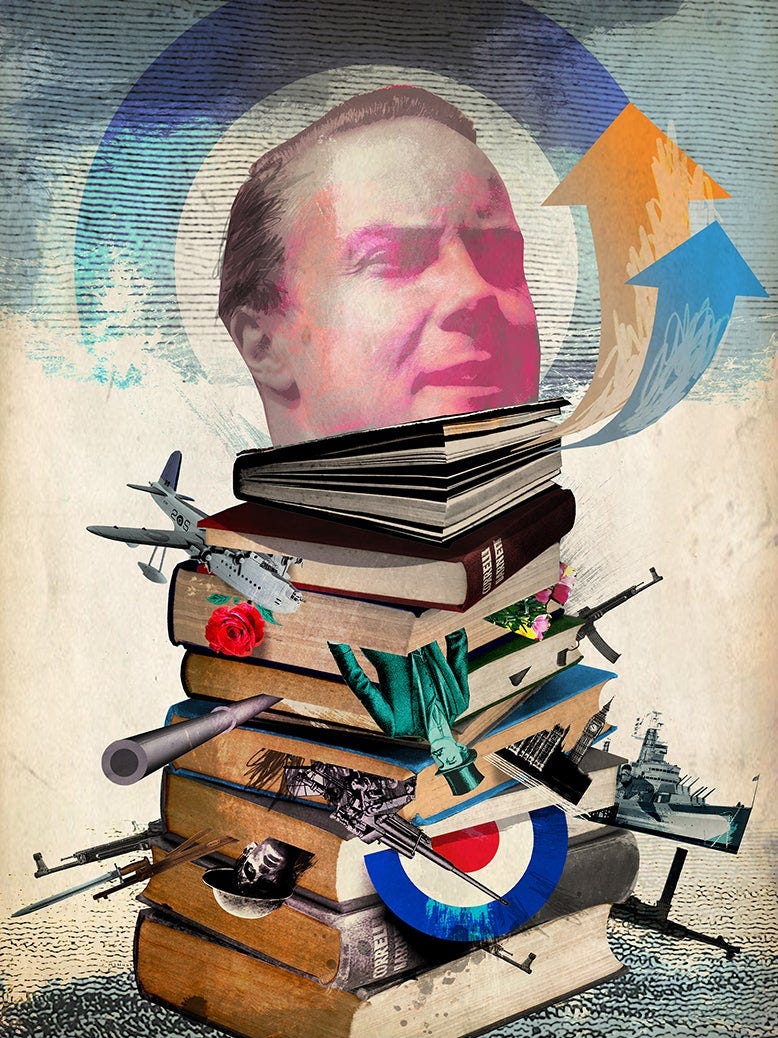

10—“The conservative underground”

Something is twisting within British conservatism, whether you’re looking at Dominic Cummings’s Substack or the attempted rehabilitation of Enoch Powell. To get a better sight of these murky currents, John Merrick traces them upriver to Correlli Barnett, the court historian of Thatcherism. NH

Analyses of our denuding economic and geopolitical condition have… often been entangled with a more emotional historical diagnosis: that these failings can be traced to a corruption at some point in our past. If those failings can be remedied, the thinking goes, then Britain can resume its exulted global role once more. The primary and most forceful exponent of this view in 20th-century Britain was the historian Correlli Barnett. And while Barnett hasn’t yet been taken up by those despairing over our national condition today – and resorting to extreme politics to rescue it – he singularly exhibits the pathologies of this pattern of thinking. In his work above all, we can find the source of the national self-loathing, geopolitical isolationism and ruthless economic radicalism currently at large.

George’s Best of the Rest

David Coates: Liberalism’s Breshnev era

Honor Cargill-Martin: Must democracy die?

Max Nelson: David Lynch and women in trouble

Daniel Immerwahr: The attention span moral panic

Faye Curran: The decline of the pauper’s funeral

Allie Volpe: “Protecting your peace” kills friendships

Jason Cowley (from the vault): Gatsby at 75: beautiful but damned

Pat P Pat, the decorated monkey who helped a World War II sergeant

Ceasefire, 1994

On Wednesday the Northern Irish poet Michael Longley died at 85 years. In 2017 he delivered a lecture, published in the New Statesman, about the troubles and the peace process, poetry and partisanship, and the horrors of war. I have long been struck by the huge debt the Irish literary tradition owes to the classics, and Longley is no exception. His poem Ceasefire compresses the Iliad’s most famous episode, as Priam begs Achilles to return his son Hector’s body. It was published in the Irish Times in 1994 the week that the IRA declared their own ceasefire. And it feels as live now as it must have done then. FMcR

i

Put in mind of his own father and moved to tears

Achilles took him by the hand and pushed the old king

Gently away, but Priam curled up at his feet and

Wept with him until their sadness filled the building.

ii

Taking Hector’s corpse into his own hands Achilles

Made sure it was washed and, for the old king’s sake,

Laid out in uniform, ready for Priam to carry

Wrapped like a present home to Troy at daybreak.

iii

When they had eaten together, it pleased them both

To stare at each other’s beauty as lovers might,

Achilles built like a god, Priam good-looking still

And full of conversation, who earlier had sighed:

iv

“I get down on my knees and do what must be done

And kiss Achilles’ hand, the killer of my son.”

— Michael Longley, © Jonathan Cape, used with permission of The Random House Group Ltd

The New Statesman is home to the finest writing on politics, culture and ideas. To stay up to date, subscribe using the link above.

— Finn, Nicholas and George.

The author says Servia is a vassal State of Russia. Is he blind or acephale? How would he classified UK and EU member states towards their absence of reaction and Sanctions in front of the Gaza Genocide?

At Auschwitz, where more than one million Jews were murdered, 15 orchestras operated?

Seriously? Like Christianity, Holocaustianity is just another power-seeking, money grubbing hustle.

The numbers of dead in the decoded messages from Auschwitz roughly correlate with the numbers of dead recorded in the Auschwitz death registry volumes. Since the Germans made their reports in top-secret transmissions using a supposedly indecipherable code, why would they report deaths from shootings and hangings but not from homicidal gassings? The Germans would have no reason to hide deaths by homicidal gassings in their secret messages if such deaths had actually taken place.

David Cole, a Jewish American, has also produced a very revealing video based on his visit to Auschwitz in September 1992. Wearing a yarmulke and pretending to be a righteous Jew wanting to answer those who question the Holocaust story, Cole paid extra for his personal English language tour guide. The video shows numerous weaknesses of the alleged homicidal gas chamber at Auschwitz: 1) Obvious marks on the walls and floors where apparently walls have been knocked down; 2) Equally obvious holes in the floor where bathroom facilities had been; 3) A flimsy wooden door with a big glass pane in it; 4) A doorway with no door and no fittings for a door leading to the crematorium ovens; 5) A big manhole right in the middle of the gas chamber; and 6) No Zyklon B staining in the walls. Any reasonable person can tell that the alleged gas chamber shown in the video could not possibly function as a homicidal gas chamber.

In response to David Cole’s questions, Cole’s tour guide repeatedly states that the gas chamber at Auschwitz was in its original state. Unable to answer all of Cole’s questions, Cole’s tour guide went to get a woman who was introduced as the Supervisor of Tour Guides for the Auschwitz State Museum. In response to Cole’s question, the Auschwitz tour supervisor states that the holes in the ceiling of the alleged gas chamber at Auschwitz were rebuilt after the war. Thus, contrary to statements made by Cole’s tour guide, the Auschwitz tour supervisor acknowledges that the alleged gas chamber at Auschwitz is not in its original state.