The Saturday Read: Paradigms lost

Inside: AI, The Finale, profiteering, Burke, Oxford, China, Kissinger, and immortality.

Good morning, and welcome to the Saturday Read, the New Statesman’s weekly guide to the best writing on ideas, politics, books and culture. This is Harry. Will, who co-writes everything in this email, has also written today’s sign-off.

This week I took the plunge that, it seems, we must all now take: I started reading up on AI. The field has three founding scientists. I met with one of them, and I hope to have more for you on that soon. Another, Yoshua Bengio, spoke to the BBC and described feeling “lost” over his life’s work, such is the threat that he fears we now face over runaway intelligence. Others in the field think these fears absurd.

Read Thomas Kuhn’s The Structure of Scientific Revolutions (1962), the slim, masterful work that coined the term “paradigm shift”, and this moment may feel familiar. Six decades ago, Kuhn explained how scientific knowledge develops – not progressively but disruptively, in moments of great upheaval that destabilise the scientists at its core. Bengio’s words echo Wolfgang Pauli’s, who wrote to a friend in the uncertain months before the discovery of a new quantum theory, “At the moment physics is again terribly confused. In any case, it is too difficult to me, and I wish I had been a movie comedian or something of the sort and had never heard of physics.” We may be at such a moment with AI.

If the pieces below intrigue, perhaps you’d like to try a trial subscription to the NS. Read three free articles after registering on our site. A digital subscription is just 95p a week. If you are already a subscriber, thank you for reading us. Let’s get to it.

1—“Of course, their union can’t last.”

Anna Leszkiewicz’s piece on this week’s major TV event – the finale of Succession – is exquisitely tuned. (NB: Spoilers ahead.) When I saw it, I didn’t absorb the meaning of the video of Logan that the siblings watch during the episode. Anna helps capture it below. (For more on Succession, see Anna’s interview with Jesse Armstrong, its showrunner, last year, as well as Olivia Pym’s reflection in our pages this week.)

But even more painful is the “virtual dinner with Pop” – a video that Connor (Alan Ruck) plays at their late father’s home. Shiv, at Logan’s funeral, tells a story of how she and her brothers would play outside his locked office. “What he was doing in there was so important. We couldn’t conceive of… of what it was… He kept us outside. But he kept everyone outside.”

Their desperation to enter that room has profound consequences. Here – watching their dad recite a long list of presidential losers, laugh at Connor’s impressions of him, and sing along with Karl’s rendition of “Green Grow the Rashes”, while Kerry cuddles up to him – they are shut out again, looking into a room they were never allowed to access, seeing a side of their father he would never show them. This has always been a show about how a traumatic childhood stalks and corrupts a grown-up family, how easily the search for love becomes the search for power.

2—“No one should underestimate how serious the threat posed by high food prices is to the social fabric.”

For our cover story this week, our business editor, Will Dunn, examines Britain’s age of greedflation. While inflation is portrayed in the news as a single number, Dunn writes that it is more “like a pandemic” arriving in waves as new forms develop. At the end of 2022 a third wave arrived. The force driving up prices? Greed.

The inflation is worst in staple foods: baked beans are up 41 per cent, sliced white bread is up 28 per cent, dried pasta 22 per cent. According to the retail data analyst Kantar, groceries now cost the average household an extra £833 a year. For a low-income family, that is already unsustainable. A recent YouGov poll of 10,000 adults found that one in five people in the UK has recently reduced the amount they are eating or skipped at least one meal due to the high price of food.

3—“There was talk of 500 drag queens – no, 1,000 drag queens! – descending on the union’s debating chamber.”

There were widespread fears – held by no less an authority than Rishi Sunak – this week that Kathleen Stock’s talk at the Oxford Union would not go ahead. It did happen but what resulted was a farce. Will was there to watch it happen.

It took ten minutes for the day to collapse in on itself. Stock was patiently explaining her position on whether trans women should be allowed to enter single-sex spaces such as bathrooms and prisons when it happened. A single clear voice, before a deluge of other voices: “Trans rights are human rights.” It was the thin student – Possnett – who had stood near me in the queue. They stood up, squirted glue into their left palm, walked calmly to the space in front of the stage, sat down and affixed themselves to a floorboard. “Oh dear,” said a voice behind my seat. Another protester at the back of the hall unveiled a trans flag. A third protester handed out leaflets (“Kathleen Stock is not welcome here…”). Those two were ushered out.

4—“‘You have supported the cause of the Gentlemen,’ King George III is supposed to have said to Burke.”

In our weekend essay, Sam Earle recovers hidden aspects of Edmund Burke, Conservatism’s philosopher king – and perhaps the first modern reactionary. Burke’s maxims are repeated endlessly by Tories, and often admired by liberals, but the truth is that he was a much more radical thinker than is usually recognised.

Burke also knew when to fight. He recognised that to defeat radicals, you sometimes needed to act like one. “To destroy that enemy,” he wrote, “the force opposed to it should be made to bear some analogy and resemblance to the force and spirit which that system exerts.” Mary Wollstonecraft saw in the intensity of Burke’s thought, in his radical commitment to defending inequalities, a revolutionary in gentleman’s clothing.

5—“Since 1982 Kissinger has been the world’s leading consultant, a business figure, not a diplomatic one.”

The centenary of Henry Kissinger was either greeted with cheers (he is a genius) or jeers (he is a war criminal). What if, Ben Judah writes, the real story – and the real Kissinger – was something else entirely?

The actual Kissinger genius over the last few decades was not these anodyne comments but the ability to listen – and therefore say exactly what the client, the sponsor or the establishment wants to hear. This is in sharp contrast to committed public thinkers on geostrategy such as Brzezinski or George F Kennan, who often said what Washington didn’t want to hear. The result is that Kissinger, far from practising what his associates such as the political scientist Graham Allison call “the moral idealism of realism”, has blown with the wind. Kissinger supported the Iraq War when it was the establishment line, the “reset” with Russia when it was popular and now, contrary to all his previous writings, the admittance of Ukraine into Nato.

From our partners

BP’s transformation is underway. While today we’re mostly in oil & gas, we’ve increased global investment into our lower carbon & other transition businesses from around 3% in 2019 to around 30% last year. From offshore wind to EV charging to oil & gas, see how we're putting plans into action.

6—“I’ve noticed how silent the Commons seems to be when he speaks.”

Rachel Wearmouth, our deputy political editor, has written a great piece on Pat McFadden, the most consequential Labour politician you’ve never heard of (he ranked 25th on our recent left power list). As shadow chief secretary to the Treasury, McFadden controls Labour’s spending plans, serving as Rachel Reeves’ de facto deputy.

McFadden is also viewed as one of the leaders of the party’s “Ming vase” brigade (an allusion to Roy Jenkins’s description of Blair before the 1997 election as “a man carrying a priceless Ming vase across a highly polished floor”). This tendency believes Labour should be cautious on economic policy for fear of jeopardising its electoral chances. Morgan McSweeney [Labour’s highly influential campaign director] and others, it is said, would prefer Labour to be bolder.

7—“I would rather end my days in an English churchyard than an American freezer.”

Martin Rees, the astronomer royal, has written for us on the increasingly well-funded quest for immortality. Does lengthening telomeres – the stretches of DNA at the end of chromosomes, which shorten as people age – hold promise as a means of extending life? Does cryogenics? And what would it mean if people (or only some people) could prolong their lives? The question is not moot. In many ways we already live with the inequalities Martin describes: life expectancy in richer areas of the UK is around a decade longer than in poorer areas.

There would obviously be a fundamental inequality between those who had taken the elixir and those who had not. And if everyone’s life was extended, how could an overcrowded and unsustainable world be avoided? And how much does this depend on the magnitude of lifetime-enhancement, from a mere doubling of lifespan to a near-permanent indestructibility? It’s a philosophical issue whether personal identity can be preserved indefinitely, so that after thousands of years you would still be you in any meaningful sense.

8—“Are you trying to get me kicked out of the party?”

For our weekend interview, George, our senior editor, spoke with Faiza Shaheen, purportedly the “only left candidate” Keir Starmer has allowed to stand as a prospective Labour MP at the next election (we’ll have to see how that turns out).

Some on the left now feel betrayed by Starmer who has discarded campaign pledges such as abolishing tuition fees and taking private utilities into public ownership. Does Shaheen? She eventually gave a careful answer: “I’ve heard a lot said about how circumstances have changed; what I’m trying to do locally with my members is to be clear about where I stand: you’re not going to hear me taking lines from the Tories on immigration or talking about tagging refugees. I don’t believe in that. I still think public ownership is a good idea.”

9—“We’re stuck paying ballooning bills to the freeholders – often faceless companies – who really own our homes.”

Anoosh, our Britain editor, reports on the great leaseholders’ revolt. “No tenants on my estate – council, private rental, or leasehold,” she writes, “have any control.” Michael Gove pledged to abolish the “feudal” system of leasehold ownership, but he has failed to do so. His plan has been dropped as a government policy. Why?

Legalistic and tedious, the pitfalls of leasehold tenancy are hardly the stuff of slogans. But the Tories take an electoral risk betraying these voters. Many are young professionals who have “done everything right” by the government, using Conservative interventions like help-to-buy and shared ownership to buy their first homes. On the brink of starting families and upsizing, they should also be teetering on Toryism as they age – a trend that has stalled.

10—“Europe will not become a vassal to China.”

As China and the EU edge ever closer to a trade war, Bruno Maçães, our foreign affairs correspondent, interviews Beijing’s top diplomat in Europe, Ambassador Fu Cong, in Brussels. Asked if China was a democracy or an autocracy, Cong gave Maçães an intriguing answer.

We see ourselves as a democracy. So that’s why we say this is a misleading narrative. Who gives a country the right to define whether other countries are democracies or autocracies? It’s dangerous in the sense that if you divide the world into two different ideologies, into two different blocs, you will be in effect taking the world back to the old Cold War days.

Best of the Rest

Daily Mail: Biden laughs off third fall this year, then bumps his head.

Nautilus: The longevity sceptic.

Guardian: Xi plans state control of AI.

Slate: Staring into the soul of the GOP. Nice to see that American politicos drink as much as their British counterparts.

NYT: Elon Musk’s weird social life. Allegedly the world’s richest man just wants to be funny.

Thomas Meaney: The literary equivalent of quantitative easing.

Phillip Schofield: “Do you want me to die?”

Lara Spirit: The many mindless WhatsApp groups of Westminster.

Larry Elliott: I can’t tell the difference between Labour and the Tories.

Peter Thiel: The diversity myth.

I think he’s a bit too old to be doing this. At least he’ll be able to afford a good nanny.

Egg vending machine. The man who built it is looking for a “love match”, God bless him.

From our partners

As interest rates rise again and food-price inflation is at a 45-year high, people are continuing to feel the squeeze on their living standards. But these costs are not felt equally; disparities across income, employment, health and housing are all driving regional inequalities. PwC has released an annual Good Growth for Cities Index, which ranks large UK cities across 12 economic success measures. Read more here.

Elsewhere on the NS

“He’s taught me that it’s actually not half bad to be alive.” Charlotte Stroud has discovered the perspective-altering essays of JB Priestley (“that ass Priestley” as Evelyn Waugh called him in his notorious BBC Face to Face interview with John Freeman, who went on to edit the New Statesman).

Lamorna Ash paid a highly imaginative tribute to her grandfather in her column this week.

We should really be more incensed by the vast sums of money Mark Zuckerberg burned in building the Metaverse, argues Sarah Manavis.

Jason, our editor, reflects on Elton John’s long, sparkly goodbye.

Andrew Marr has coined a new demographic: “Mavis” – the middle-aged, volatile and insurgent voters reshaping Britain’s politics. Who are they?

Armando Iannucci, like many others in Britain, cannot think of a single “landmark Tory initiative in the past 13 years that’s been of lasting benefit to the country”.

“In 1965 the architect Leslie Martin was commissioned to design a new ‘government quarter’ for Whitehall. A platform of ziggurats was proposed over a motorway leading from Victoria Street to the British Museum. Such was the ethos of the day that such colossal destruction evoked little comment.” Simon Jenkins revisits the extraordinary postwar plans for the architectural reinvention – or rather, demolition – of London.

Perhaps you might like our daily political email. One in five Saturday Readers subscribe.

How to get into: American power

Each week we ask someone to recommend three books as a way into a subject. This week we turned to Gavin Jacobson, our ideas editor.

Kissinger’s Shadow: The Long Reach of America’s Most Controversial Statesman by Greg Grandin (2015): “Once you’ve been to Cambodia,” the late Anthony Bourdain once said, “you’ll never stop wanting to beat Henry Kissinger to death with your bare hands. You will never again be able to open a newspaper and read about that treacherous, prevaricating, murderous scumbag sitting down for a nice chat with Charlie Rose or attending some black-tie affair for a new glossy magazine without choking. Witness what Henry did in Cambodia – the fruits of his genius for statesmanship – and you will never understand why he’s not sitting in the dock at the Hague next to Milošević.” Grandin’s biography is the indispensable account to read in the wake of Kissinger’s 100th birthday last weekend.

American Foreign Policy and Its Thinkers by Perry Anderson (2015): A masterful survey of US grand strategy and its architects, Perry Anderson’s slim volume is a vital enchiridion for understanding the goals of American foreign policy since the birth of the Republic to the Barack Obama administration. Anderson shows that key theorists (“spear-carriers of empire” in Chalmers Johnson’s phrase) – including Walter Russell Mead, John Ikenberry, Zbigniew Brzezinski and Francis Fukuyama – have been concerned not only with national security but making the world safe for capitalism under the aegis of American might.

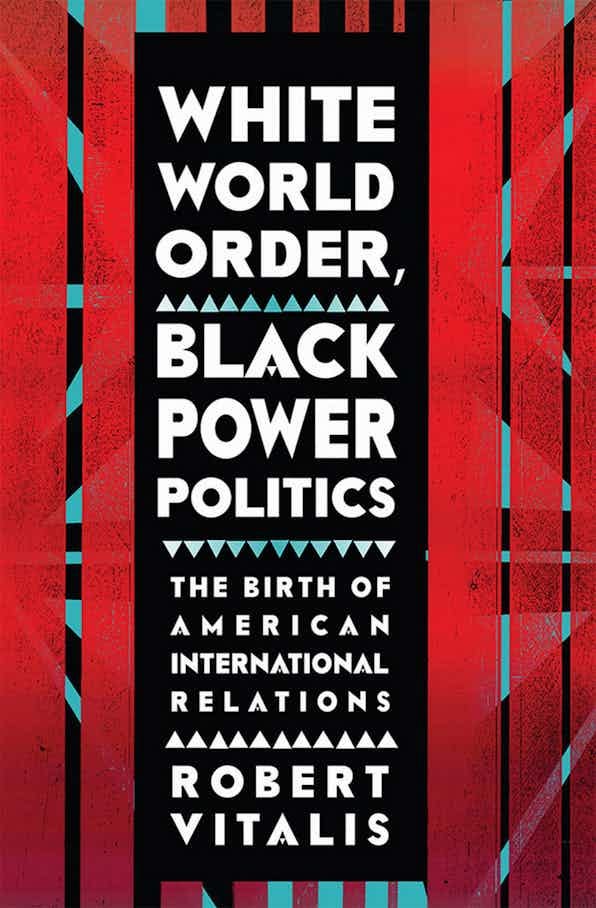

White World Order, Black Power Politics: The Birth of American International Relations by Robert Vitalis (2015): In 1910 The Journal of Race Development was established as an academic journal of international relations. It signalled the centrality of “race” to political science at the time. A few years later, the title was bought and renamed Foreign Affairs, now the in-house title of the DC Beltway. This fascinating detail is one of many in Vitalis’s critical history of how the field of IR in the US was developed to serve the interests of imperial power and to justify the claims of global white supremacy in a multiracial and increasingly interdependent world.

And with that…

On Monday afternoon I watched Sally Rooney talk to Annie Ernaux at the Charleston Literary Festival. Charleston was once the home of Vanessa Bell, the English painter (and Virginia Woolf’s sister). The house is somehow both damp and well looked after; its walled garden, lake and grounds tended to with as much sagacity as they were when the Bloomsbury Group used to lay around the place, arguing about beauty and sleeping with one another. Really, if Charleston tells a story, it’s a generational one. Bell and her friends were living off the rock-solid dividends and stable money of their Victorian parents. The profits of empire supplied an Edwardian garden with flowers, and the Bloomsberries with the means to avoid doing much work.

I drank an absurdly strong Negroni and entered the tent where the two authors were due to speak. Rooney asked good, thoughtful, attentive questions. Ernaux replied, and expressed her words with her hands as she talked. An interpreter finished off her answers in English for the audience. The Nobel Prize in Literature, which Ernaux won last year, had given her writer’s block for the first time in her life. She said she found it impossible to do any writing: writing was her future, and her pleasure, and she felt as if it had been taken from her. Reluctantly, Ernaux’s words reminded me of Woolf’s last diary entry, and her sense of being “nipped & silenced”. Woolf was writing about her depression and Ernaux was describing the consequences of success. Few realise that they can be the same things.

Thank you for reading. Don’t miss out – subscribe to the New Statesman and stay up to date with everything you need: from news and analysis to comment and criticism.

Whether you’re looking for a sharp blog or a finely written feature, the New Statesman has you covered. Have a good week, and catch you next Saturday.

Thanks to our colleague Chris Bourn on this week’s edition.

Looking forward to reading Anoosh’s piece - though I have to warn as the owner of a flat in Scotland that things aren’t all rosy without leasehold either. Without any central organising body, any repairs to the building involve getting 16 other owners’ agreement (many of whom are landlords who don’t spend any time on the building), and there’s no provision at all for much needed maintenance