The Saturday Read: Sinister chords

Inside: Bill Gates, Da Vinci vs Michelangelo, Trump's cabinet, Hollinghurst, 100 years of Magic Mountain, and Ireland at the polls.

Good morning. Welcome to the Saturday Read, the New Statesman’s guide to politics, culture, books, and ideas. This is Finn with Nicholas, Pippa and George.

It has been a year of highly consequential elections - most obviously Labour’s loveless landslide over the summer and the fighting return of Donald Trump and the Maga vision to the United States. Finally, the Republic of Ireland headed to the ballot box yesterday, as the country is faced with a maddening question: status-quo or status-quo?

Thanks to the vagaries of Ireland’s political system, the two traditional parties of government - Fine Gael and Fianna Fáil - cohere around a liberal centre. Even Sinn Féin - a party that once optioned itself as the “change” candidate - has been dragged to the middle in a bid to gain mainstream electability. The result is a country run by an establishment hegemony with a disunited fringe.

Earlier this month I headed to Dublin, my home town, to report on this election. I found two Irelands on the doorsteps. One was of the liberal centre who preach fealty to Silicon Valley and is nervous to discuss immigration. The other was the Ireland that rioted last November in protest of immigration, the disaffected communities that threaten to burn down prospective asylum centres. Neither of these places know how to speak to one another.

Ireland and England are not the same. (The mountain of cash that Ireland is currently sitting on makes its problems distinct to its oldest and closest neighbour.) But the two nations share some parallels: the Dublin riot, in many senses, prefigured the tension unleashed on English streets in the sweltering heat of this August. These are two places where a long simmering resentment quickly spilled over into something much more dangerous.

Thanks for reading, and see you next week.

The picks…

Good morning, George here. We hope you enjoyed Jason’s interview with Bill Gates on Thursday. Below you’ll find another blockbuster – Pamela Dow on HR’s hostile takeover of Britain – among the usual range of politics and culture. In my pick of the week, Michael Prodger investigates the subtle world of Renaissance drawing. And keeping with the visual-media theme, Nick signs us off with some observations on the great photographers of the 1980s. As ever, thanks for reading and have a good weekend.

1—“No normal economy”

Analysts think Russia has shrugged off the worst effects of Western sanctions. Look closer, writes Will Dunn. You’ll find runaway inflation, ratcheting interest rates, a dysfunctional war economy and a national dependency on a volatile commodity: oil. NH

In the long term, what has long been evident is that Putin’s presidency has been little different from the Soviet era, in that he has made Russia a military giant but an economic dwarf. His gangster state has never been able to diversify; while the world buys Chinese cars and American software, the only thing we buy from Russia is oil, and the gradual turning away from hydrocarbons will eventually expose this as an appalling waste of a country’s potential… If Russia’s economy is roaring, it is roaring with dismay.

2—“A ragtag bunch”

If Donald Trump’s electoral coalition seems incoherent, his cabinet appointees are even more so, comprising everyone from exiled Democrats (RFK Jr) to silicon valley libertarians. This motley crew might hold together, Jill Filipovic writes, because Trump’s currency is loyalty, not politics. NH

In fascist Italy, Benito Mussolini enjoyed support not just from fascists but from Catholics, nationalists and even liberals; in Germany, Adolf Hitler’s policies were broadly popular across a diverse swath of the population. And elevating seemingly ridiculous figures to power is part of the autocrat’s game. As the historian and writer Anne Applebaum, who has spent her career writing on authoritarianism, recently said in an interview, people who are “given jobs because of their level of their loyalty to the leader… is one of the things that characterises an authoritarian regime”. Part of that loyalty test, she said, is very often “the forcing of people to adhere to a conspiracy theory or say things… that are patently untrue”. Team Trump’s demand that Republicans agree with the patently false claim that the 2020 election was stolen is one example

3—“Sublime gifts”

We can conjure from memory the great works of Da Vinci, Michelangelo and Raphael. But what about their first drafts? Michael Prodger reviews two exhibitions of Renaissance sketches, and finds new depths to these divinely talented artists. FMcR

By this time, however, jealousy meant that the older pair were already prickly with one another. Leonardo was one of the artists (Botticelli and Piero di Cosimo were among the others) convened by the Republic to advise on where best to site the David. Leonardo wanted it tucked away under the Loggia dei Lanzi, opposite the Palazzo della Signoria – the seat of government – denying Michelangelo as much glory as possible. He was outvoted and over the course of four days it was inched into position, in full public view, in front of the Palazzo.

There was, therefore, an element in mischief in the ruling council commissioning both Leonardo and Michelangelo to paint battle scenes for the Great Council Chamber, the Sala del Gran Consiglio, as part of a decorative scheme celebrating Florence’s escape from Medici rule.

4—“Damaged candidate, damaged party”

Ahead of the election on 23 February, Olaf Scholz is on course to be the first German chancellor since the 1970s to be voted out after just one term. Behind the collapse? Scholz’s fairy tale belief in the boundless power of green energy, Wolfgang argues. FMcR

Scholz’s coalition was also one of the biggest supporters of the EU’s Green Deal, with its compulsory CO2 targets for car companies, a 2035 ban on the sale of new fuel-driven cars, a nature restoration law that forces farmers to set aside land and now a law that demands businesses prove the products they sell have no connection to deforested land. Along with legislation on corporate social responsibility, this has all led to a big increase in costs and bureaucracy for companies. The electoral pushback is the first popular revolt against net zero in Europe. It will not be the last…

This is what happens when a country with an outdated technology hits the net-zero economy amid geopolitical conflict.

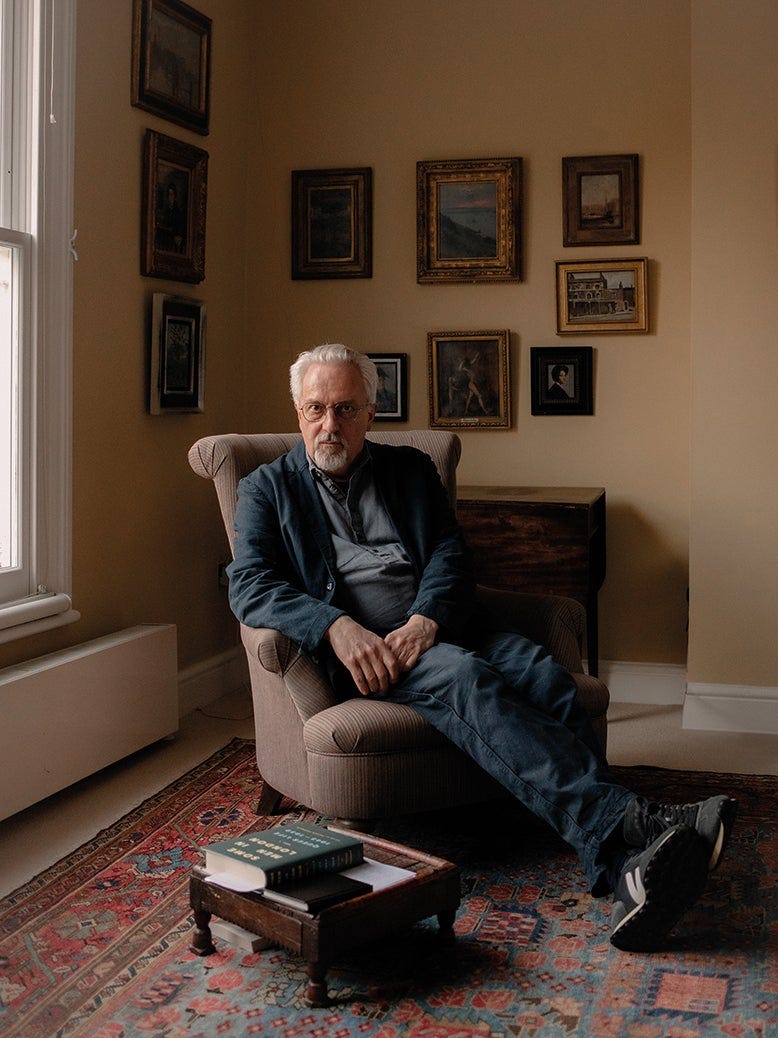

5—“Reconjuring lost Englands”

I am increasingly convinced Alan Hollinghurst is among our greatest living novelists, and it was therefore an immense pleasure to profile his life and work this week. We discussed his new book, Our Evenings, but also his enduring preoccupations: English history, upper-class hypocrisy, and the crime of gay repression. NH

The amateur historian is a recurring figure in Hollinghurst’s work: the private memoirist, the commissioned biographer, and then, more ambiguously, the photo-album rummager and prying researcher, assembling lost letters, papers and poems to reveal buried truths… Characters and sometimes entire families are shown to move through decades of England’s 20th and 21st centuries to the present, burdened with the experiences and indignities that have framed their lives – racial in Our Evenings, but social and sexual in his earlier books. This recasting of English history arguably constitutes the unifying theme of Hollinghurst’s fiction.

To enjoy our latest analysis of politics, news and events, in addition to world-class literary and cultural reviews, click here to subscribe to the New Statesman. You'll enjoy all of the New Statesman's online content, ad-free podcasts and invitations to NS events.

It’s 150 years today since the birth of Winston Churchill. A memorial issued at his funeral unhesitatingly called him “England’s greatest son”. He also topped the BBC’s “Greatest Briton” poll in 2002. In certain circles today, however, his name is met with ambivalence, even hostility.

But such circles went unrepresented in the crowd of 700 who packed the Royal Geographical Society in Kensington on Thursday to hear biographer Andrew Roberts discuss the statesman. The audience’s sympathy even breached the sartorial: it is said Churchill never saw a hat he didn’t like, and neither had they. The heads beneath this sea of trilbies tended towards the grey. My grandma, though, who remembers the war, said “What a youthful crowd!” So it’s a question of perspective.

David Reynold’s reminded us last week that Churchill was as funny as he was bulldoggish. Now that you can pass through the national syllabus with scant reference to the man, lessons like this are worth remembering. The talk ended with a joke. When told a Downing Street cook had fallen pregnant after a “nocturnal assignation” with a man she met in the streets of Verona, Churchill replied “Not one of the two gentlemen, then!”

Artificial intelligence is fast becoming a part of life as the UK strives to become a global AI superpower. But do we have the talent, skills and regulatory framework to deliver on that?

We hosted a fascinating discussion with 3M, and technology and business leaders, to explore how Britain can accelerate AI-driven innovation. Watch the full discussion here.

6—“Gates’ warning to the world”

For this week’s cover story, Jason interviewed billionaire philanthropist Bill Gates. He describes himself as an optimist, but he is anxious that the spirit of global collaboration that existed at the turn of the millennium is fading. Today, the world, he says, is at a dangerous tipping point. PB

Here, then, is the optimist’s dilemma in microcosm: the world is not as Bill Gates wishes it to be or believed it once was or would like to imagine. History does not move progressively forward in a linear way. In a world in turmoil the gains of progress can be reversed or lost. His priorities – as one of the world’s richest men and greatest philanthropists – are increasingly not shared by nation states committed to national exceptionalism and to spending more of their GDP on defence and security. The potential for technological innovation, Gates believes, is boundless, and yet something has been lost, the spirit of transnational and multilateral collaboration that illuminated the early years of the century. How do we encourage every nation to do what it can to help the poorest in a zero-sum world? Gates seeks light but darkness is visible everywhere.

7—“Not parliament as usual”

Yesterday, MPs backed assisted dying by 330 votes to 275. Rachel Cunliffe was in the House of Commons to watch this historic moment unfold. The debate was intense and emotional, she told me. But parliament did what it does not usually do: debate legislation properly. FMcR

By the time the debate began, we were familiar with the arguments for and against. We have heard them all: the case for humane compassion, for choice, for a “good death” and for alleviating terrible suffering, set against anxieties about the “slippery slope”, the risk of pressure and coercion, and crossing the so-called Rubicon by giving the state the right to end lives. We have seen them play out in newspaper columns and in television studios, harrowing personal stories (from both sides) set against medical and legal expertise (from both sides). Many of us will have heard something that changed our minds on this most serious question, only to hear something else that changed our minds again. Indeed, the same will be true for many MPs.

8—“A civilisation struggling to breathe”

Thomas Mann’s Magic Mountain is 100 years old this month. Tanjil Rashid travelled to Davos, where Mann first conceived the novel. Set in an “incurably sick Europe”, Mann captured a seductive blend of ideology and nihilism. No, doesn’t sound familiar at all… GM

How many young men today, from the incel to the Islamist, feel drawn to that perverse vision, who think, “what our age needs, what it demands” – as Naphta says – “is terror”? Even on my first reading The Magic Mountain in the feverish years after 9/11, when the cult of death had re-emerged once more as the zeitgeist, Naphta’s justifications struck a sinister chord in my own disaffected mind, disaffected with the West and its hypocrisies.

9—“An HR superpower”

In September, a report titled “Foundations” detailed Britain’s struggle with growth, productivity and state capacity. It blamed complex tax codes, overactive lobbyists, and a reluctance to build. Pamela Dow explains that it should have considered the vice-like grip of Britain’s HR sector too. PB

If we could track trends towards higher retention, happier workers, fewer grievances, this growth would be welcome. If there was a correlation with HR and improved outcomes it would be rational for leaders to invest more. There is evidence for the opposite. As HR roles have increased so too have the number of tribunals and days lost to work-related illness, while productivity has flatlined. HR expansion is not coinciding with desirable things and appears to be coinciding with undesirable ones.

George’s Best of the Rest

Thomas L Friedman: The world has changed since Trump was president

Fintan O’Toole: Ireland is rich but not happy

Janan Ganesh: We need EuroMusk

Becca Rothfeld: We used to call nostalgia a disease. More sensible days. I miss them!

James Marriott: Woke is waning, but was it ever more than a fad?

Kenan Malik: Defend the obnoxious

Adam Moss: How Jonathan Franzen learned to write Jonathan Franzen novels

Sheluyang Peng: Nietzsche’s eternal return in America

And with that…

In the 20th century we traded regnal eras - the Edwardian or Victorian periods, for example - for the more arbitrary “decade”. But which can you visualise more vividly, “the Sixties” or “the Elizabethan”? As if to prove the point, this week I visited the Tate Britain’s excellent new photography exhibition, “The 80s”. The decade curates itself: the miners’ strike, the Troubles, urban riots, racial politics and the rise of the yuppie. The exhibition is blessed by a generation of talent that witnessed these scenes, from Don McCullin to Martin Parr.

Parr is among the period’s greatest documentarians. Until I visited this exhibition, I had not realised how uncommon it was for photographers to work in colour film, preferring monochrome all the way into the late Seventies. But with his gaudy palette, Parr’s semi-satirical, semi-kitsch photographs of class in England capture the new age of consumerism at its most vivid. His picture of Conservative toffs (titled “Conservative Election victory party”) is the most striking, capturing the beneficiaries of the Thatcherite age in all their pasty glory.

— Nicholas

The New Statesman is home to the finest writing on politics, culture and ideas. To stay up to date, subscribe using the link above.

— Finn, Nicholas, Pippa and George.

Great read. Perfect title. Thank you once again.