The Saturday Read: Summer's lease

Inside: Virginia Woolf, disaster nationalism, and the Olympics.

Good morning. Welcome to the Saturday Read, the New Statesman’s guide to politics, culture, books, and ideas. This is Jason, together with Finn, Nicholas, Pippa and George.

This week’s magazine is a bumper summer special. (Bumper: an archaic word used only in the media by editors promoting special seasonal print editions.) The issue features some of our favourite cultural essayists – Anna on Virginia Woolf, Kate on Žižek, David Hare on the press, Rowan Williams on conservatism, Helen Macdonald on nature, Ed Smith on sport and art, Richard Harries on the remoralisation of politics, Edward Docx on Beethoven, and much more.

Perhaps my favourite piece is the great John Gray on French historian Marc Bloch’s L’Etrange Defaite (Strange Defeat, published posthumously in 1946). In a recent interview with the Economist, Emmanuel Macron said that to understand the risks and threats facing Europe today we should re-read Bloch, who having joined the Resistance was captured by the Nazis, tortured and shot dead with 27 others in 1944. I asked John to do just that – to re-read L’Etrange Defaite.

What did Bloch know? And what had led to the catastrophic fall of France? For Bloch, France’s collapse was caused by what he called “the ideology of international pacifism”. Through the media and education system, John writes, “a generation was taught that patriotism was the principal cause of war. The modes of warfare fomented and waged by rising authoritarian powers were not understood, or ignored.”

Here then, as Macron said – and as all eyes are on Paris for the Olympic Games and following the sabotage attacks on the French high speed rail network – is a warning from history. Do read John’s essay – and Bloch’s book – and I hope you enjoy the bumper summer special and today’s newsletter.

The picks…

Morning, Nicholas here. For the second Sunday in a row, the New Statesman’s regular programming was interrupted by dramatic news from America. Biden’s long-awaited withdrawal from the presidential election may have been less shocking than Trump’s shooting, but it marks the end of a long and eventful political career, and a presidency that was far from inactive on policy terms. Sohrab Ahmari pays tribute to the era of Bidenism below. Elsewhere, as politics begins to tread more lightly on our lives in the UK, we have an eclectic range of literary essays, sharp columns and fascinating interviews. To close, Finn signs us off with some thoughts on the Paris Olympics.

1—“Bidenism could be remarkably populist.”

Given that the Democrats marketed their 2020 candidate as the solution to the Trump problem, Biden borrowed deeply and liberally from his political playbook (from tariffs on Chinese goods to industrial onshoring). This was an economic agenda suited for a post-neoliberal age, writes Sohrab Ahmari in an admiring elegy to Bidenism, even if it failed to crack the immigration problem. The challenge awaiting any successor is to finish the job. NH

Can Kamala Harris – as either the Democratic nominee or the president – chart a different course? Would she even want to? Or would she ditch the populist elements of Bidenism and revert to some version of Clintonism-Obama-ism: that is, technocratic tweaks to the still-kicking neoliberal order combined with aggressive cultural progressivism? It’s hard to say, in large part because Harris is a policy cypher. In the event, the populist revolt hasn’t abated.

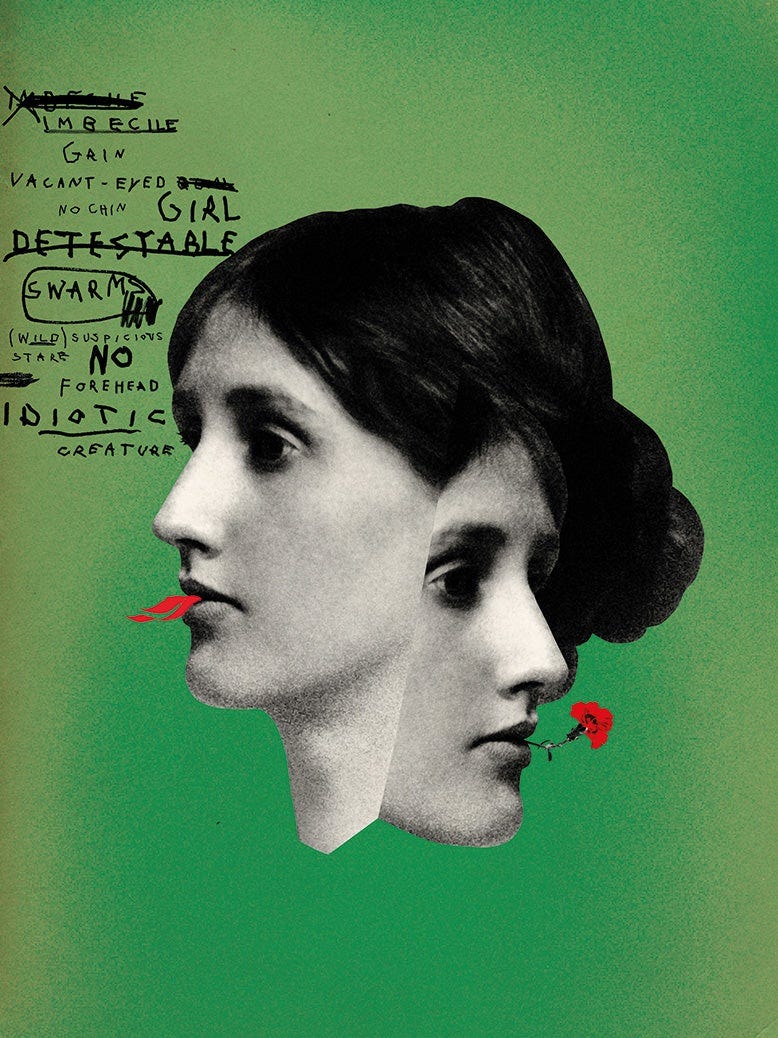

2—“Woolf’s cruel language is a symptom of her own fears.”

A statue of Virginia Woolf in Bloomsbury has been fitted with QR code postscript. Follow the QR code and you will be led to a website apologising for the author’s offensiveness. Most likely, the seven year old quoted here (troubled by Woolf’s harsher comments) has not read all five volumes of Woolf’s diaries; Anna has. She weighs in to set things straight. Has the council gone woke, or was Woolf truly “jarring”? GM

More than 100 years after Woolf wrote that notorious diary entry, she can be found on the very same stretch of towpath in Richmond. It’s a monument that takes a markedly different approach. Here is a bronze, life-sized statue of Woolf sitting on a bench, turned to the empty space beside her, her arm outstretched along the bench’s back, as if waiting to put her arm around someone yet to sit down. This is a warmer and more welcoming Woolf than the one I have in my mind, who I imagine preferred to do her people-watching from a slight distance. Here, she looks cheerful, inclusive, photo-ready. Tourists and walkers sit beside her and take selfies. Woolf sits silently, and smiles.

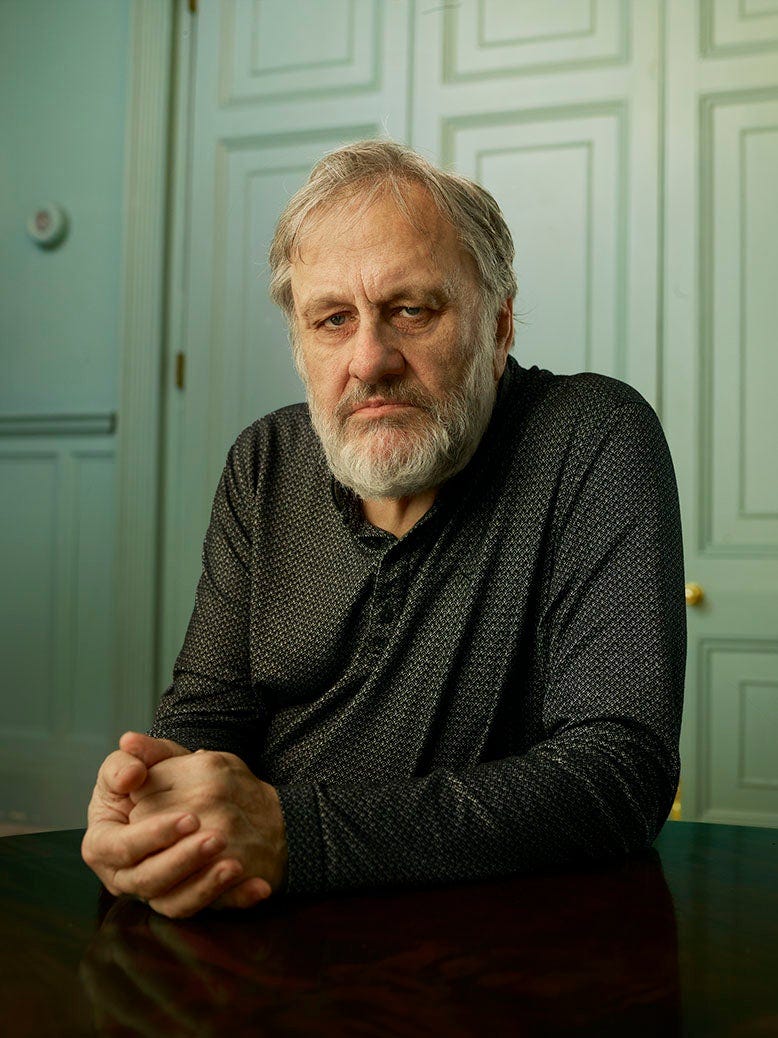

3—“Žižek’s war with the left.”

Kate Mossman visited Slovenia to spend time with Slavoj Žižek, who turned 75 this year. In the resulting wild ride of an interview – unpredictable, funny, provocative – the “rock star” intellectual covers his rejection by the mainstream media, the death of his mother, his “love” of Stalin, and so much more. PB

Žižek can’t stop talking, but he can turn up on time. He is always early for our many meetings, which take place over two days in June. While his home is off limits, his city, he claims, is entirely uninteresting – but we take a tour of it anyway in the warm rain. He has brought me an umbrella; he also has his own – he pats his top pocket – which in Žižek language is “of anal [pronounced annal] character”, meaning compact and easy to hide. Žižek has the obsession with the bodily and the filthy that often hangs around the great intellectuals, yet he is also very proper. He constantly checks for reactions to his jokes, to see if he’s gone too far.

4—“The EU is like the Holy Roman Empire in its decline.”

L’Etrange Defaite (Strange Defeat) by French historian Marc Bloch – a study of how France fell to the Nazis, published in 1946 – had long been consigned to the annals of history. In May Emmanuel Macron brought it back to life when he cited it in an interview as the best explanation for the dangers facing Europe today. The France chronicled by Bloch shares troubling parallels with today: a glut of careerist elites who failed to take the continent’s defence seriously; a refusal to acknowledge how war has changed with modernity; an inability to understand the enemy’s motivations. Jason asked John Gray to review this remarkable book. FMcR

The collective mindset Marc Bloch found in the societies he studied has broken down. The liberalism he gave up his life to defend has all but disappeared. A hyper-liberal progressive creed dismisses European civilisation as a monument to white supremacy, and the radical right is filling the cultural and political void. If the continent was ever governed by liberal values, it is no longer. Economically dependent on autocratic states, morally disarmed and seemingly possessed by a death wish, Europe is drifting towards a defeat stranger than any Bloch could have imagined.

5—“Ideas have been focus-grouped out of the public realm.”

When we compiled our Left Power List in June one thing stood out to us: the Labour Party had no backing in popular culture. Blair had Blur and Corbyn had Stormzy… why couldn’t Keir Starmer procure a rock star for the Labour project? This week I returned to the question of the party’s tricky relationship with culture. Starmer says he has no favourite novel, no favourite poem. It is almost as if he wants us to believe he has no intellectual hinterland at all. Why? FMcR

Could it be that abstract ideas have been focus-grouped out of the public realm? In Tony Blair’s wake, the field of vision has contracted, leaving politicians to declare their interest in cartography while eschewing their passion for subversive Scottish literature (a later Kelman novel, How Late It Was, How Late, won the Booker Prize in 1994). Perhaps it is electorally expedient (though I suspect the old line of attack about Britain’s national philistinism has been exaggerated). But politics needs complex ideas and ambition to work beyond the short term; without it, we risk managing our own decline through the fear of intellectual imagination.

To enjoy our latest analysis of politics, news and events, in addition to world-class literary and cultural reviews, click here to subscribe to the New Statesman. You'll enjoy all of the New Statesman's online content, ad-free podcasts and invitations to NS events.

6—“Sport and art trespass on each other’s territory.”

Ed Smith enters Cambridge’s Fitzwilliam Museum for the first time, three decades after he passed it daily as an undergraduate, for an exhibition marking the centenary of the 1924 Paris Olympics. Why, he wonders, has the tradition of sports painting failed to develop over the 100 years since? PB

The exhibition, which features Pablo Picasso, Robert Delaunay and André Lhote among others, is universal. In demonstrating the interrelatedness of sport and art in 1924, the show captures a particular cultural moment. Sport had suddenly caught artists’ attention, especially the cubists and the futurists, and the culture of games and competition looked like the future of art, not just the future of entertainment.

7—”It is not yet fascism, but something else.”

Something – the hard-right, the far-right, inchoate right-populism – is on the march, in Europe and America. Here, Richard Seymour takes one of the best runs yet at theorising this movement. Less brutally utopian than interwar fascism, it is an ideology of defensiveness and nostalgia – “disaster nationalism” – and it has mainstream liberalism on the run across the West. NH

What the new far-right offers is, as Trump often puts it, “winning”. When people are victimised by remote, abstract forces like capitalism or climate change, they often feel impotent to do anything about it… Even if we dimly sense that the system is to blame, we can’t take capitalism to court or have it shot. And where is the alternative? This is part of the general depression that is abroad. But disaster nationalism offers, instead, a politics of revenge. It identifies a series of phobic objects who can be punished and killed: migrants, “Antifa”, “cultural Marxists”, Muslims, “globalists”, Jews and “terrorists”.

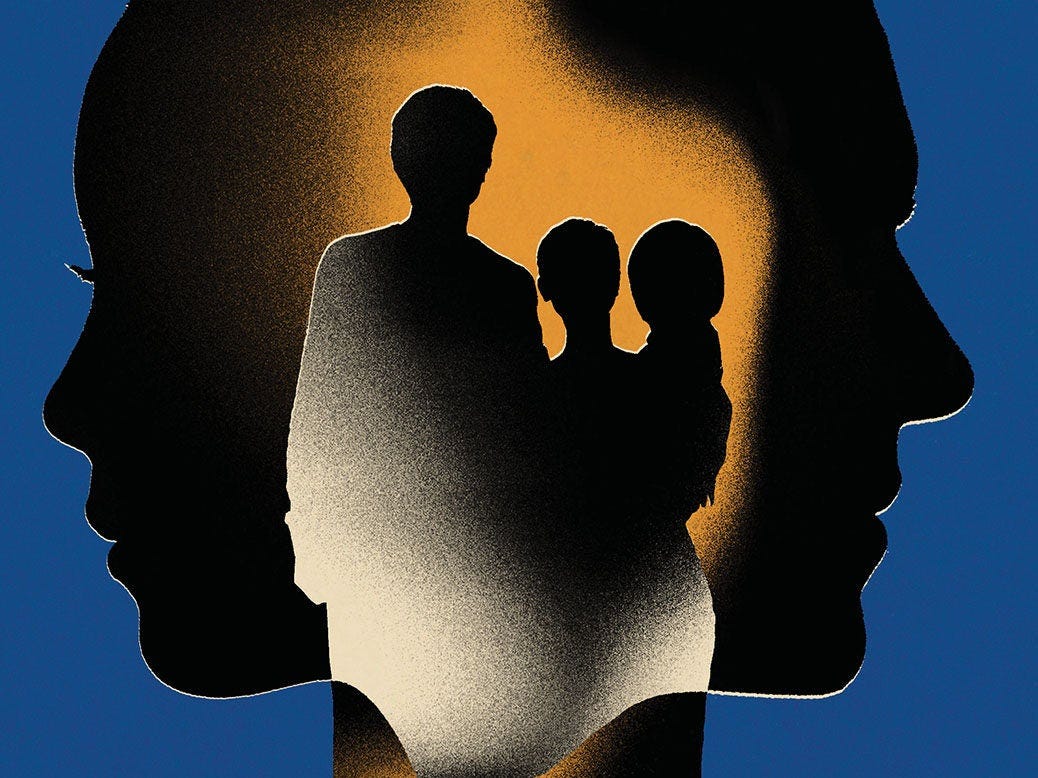

8—“Millennials act like eternal children, never ready for anything.”

Millennials are neither going forth nor multiplying, a new book argues. And this isn’t thanks to the usual economic pressures cited in declining birth rates, What are children for, contends. Instead it’s about this cohort’s fundamental attitude to life. They want a slow, perfect, and unlikely love before they even think about kids. Ann Manov finds it an exemplary bit of philosophy. GM

Earlier generations jumped into parenthood younger and poorer than we did; but we, even – or especially – when we have good jobs, stand nervously at the water’s edge. Largely drawing on surveys and interviews, the authors poignantly evoke a liberal world of neurotic individuals paralysed by choice, thinking about love, parenthood and creative fulfilment like a grocery shopper in the toothpaste aisle. We won’t have children until we have a perfect love (“I want 90, 95 per cent compatibility,” one woman says, not 70 per cent, like her friends have).

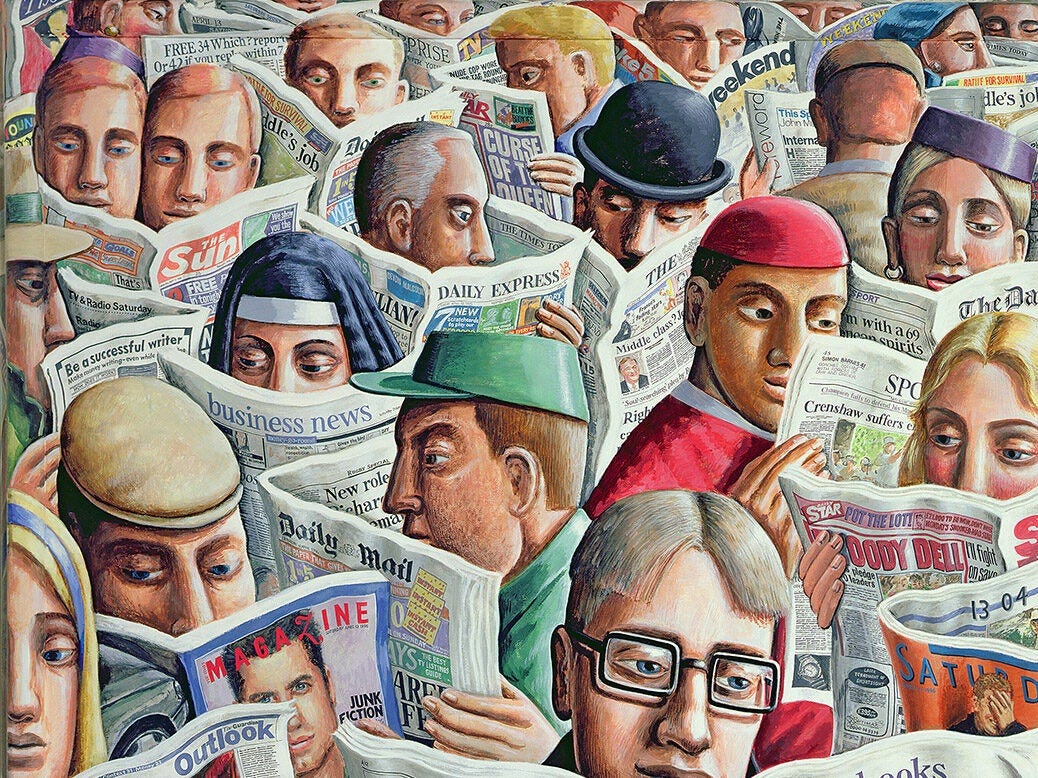

9—“If I had a pound for every article that was structured round that proposition…”

The Telegraph ran the headline “Starmer’s worst mistake yet” – five days into Starmer’s premiership. David Hare sees the funny side in such an extreme case, but also argues that the disconnect between press and public is one of our nation’s greater ills. GM

William Hazlitt said that he never picked up a newspaper without a sense of anticipation, and never put one down without a sense of disappointment. I can think of few pleasures in life greater than buying a couple of broadsheets and getting on a train. I love print. But if I were now an editor, I would make it a sacking offence to go on representing “real” people as prejudiced and chauvinist in order to advance a dead argument about the governing class knowing nothing. Democracy has just delivered a group of highly educated people who hope to use the privileges of their education to govern well. Sneering at them for that desire is a mug’s game – or contemporary journalism, as we call it.

10—“There is a real risk Ukraine will fall.”

Keir Starmer might be inheriting the bleakest geopolitical landscape of any 21st-century prime minister, perhaps even since the Second World War. Brendan Simms, historian of international relations, explains the stakes – for Labour, the country, and the West – in a typically commanding essay. FMcR

Deterring Russia will not win Labour the next election, but failing to do so would be this administration’s defining legacy. If the new government builds a whole “New Jerusalem” of homes and jobs it will earn nothing if Ukraine and parts of the Baltic fall to Putin. The resulting refugee influx and increased defence expenditure will render those triumphs nugatory. That said, if Keir Starmer does not build a single new house, or open any new school, or curb any more emissions, but manages to contain Vladimir Putin, then he will go down in history as one of our greatest prime ministers.

George’s Best of the Rest

Edinburgh’s Broughton Spurtle has achieved the Platonic form of the local news story: What is this bit of road paint?

BBC: Manchester police officer suspended after kicking video

AP: Saboteurs paralyse French railways before Olympics (Meanwhile in Britain: adventurous pet tortoise paralyses Ascot railways)

Christian Wiman: Seamus Heaney: Music and mystery

Will Lloyd: Saintly quest of eco-zealot will lead more astray

William Fear: The philosophical genius of PG Wodehouse

Elias Wachtel: On the Appalachian Trail, I fell in love with America

Naomi Kanakia: It’s OK to take a book seriously The Very Hungry Caterpillar vindicated

Stephanie Burt: Who’s cooking? Formalism and younger poets

Paul Franz: Read James Salter

“I’ve tried 50,000 beers” And I would try 50,000 more!

And with that…

There is perhaps no country with a greater national slogan than France: Liberté, égalité, fraternité really is one for the ages. Why, then, did the Olympic opening ceremony in Paris last night read more Eurotrash than Great Republic?

Nick reviewed the spectacle in detail here. It had all the turbo-pageantry of Eurovision: Céline Dion, Lady Gaga, an Eiffel Tower laser show. And, an attempt at French intellectualism: Bizet, Debussy, Macron... The scenes of athletes carted down the Seine in boats amid a genuine downpour offered a moment for Anglo-French solidarity (England is not the only place where it rains, we were reminded).

The games have kicked off in a Paris beset by a serious sense of unease. Arson attacks on French railway paralysed travel across the country yesterday, scuppering the plans of about 800,000 passengers. And the recent election - a far-right surge, rebuffed by an unhappy left wing coalition - has set the nation on edge. Could the Olympics offer a unifying bandage to a nation with a fractured soul?

We might be reminded of the London Olympics in 2012 and Danny Boyle’s triumphant (if kitsch) opening ceremony. Only one summer prior the city had been set ablaze, consumed by riots and generalised civil unrest. The Olympics did not quite propel England to the end of history - a fully liberalised, tolerant and happy place - but they did return a sense of civic nationalism to a country that had lost sight of the prospect.

It is not as if Paris had only known cloudless harmony until recent years. But perhaps the games could offer a similar, momentary salve. After all, there are very few occasions that provide such an obvious chance for national re-definition. This is one of them.

— Finn

The New Statesman is home to the finest writing on politics, culture and ideas. To stay up to date, subscribe using the link above.

SIR STEER CALMER

… a new slogan just for you to adopt Andrew Marr, since being an optimist, you're my favourite journo at the moment.

This should work at the level where populism energises people. Grab the public imagination before the naysayers get stuck in…

I'm guessing you won't read this, since you'll be on holiday. But I’ll say it anyway: yet again, so much can't-miss reading it's almost propelling me into a major calendar revision. More slots to get through Saturday Read, but then, what can I delete to make room for it? What a quandary…