The Saturday Read: Tears in the rain

Inside: Blood Meridian, diaries, Bibby Stockholm, Niger, Meloni, and accidental lives.

Good morning, and welcome to the Saturday Read, the New Statesman’s weekly guide to the best writing on ideas, politics, books and culture. This is Harry, along with Will.

I hope you are enjoying the calm of August. Time moves different in summer. I hope you enjoy today’s edition too – there are some pieces here that really struck me.

If so, perhaps you’d like to try a trial subscription to the NS. Read three free articles after registering on our site. A digital subscription is only 95p a week. Let’s get to it.

1—“In the end its beauty is mute and distant, unable to intervene in the wreck of human affairs.”

Nick Burns has written The Piece on Blood Meridian, the one Cormac McCarthy book that seems to lure readers of every type. Fine, fine writing. HL

Racism is not beyond the novel’s panorama: McCarthy’s Glanton appears as an avatar of white supremacy, directing the slaughter of peaceful and warlike native Americans alike, of Mexican villagers, vouchsafing his hatred of Indians at critical moments and even expressing an outlaw’s remorse for his brethren (“I don’t like to see white men that way. Dutch or whatever.”) But his eventual fate – head cleft in twain by an Apache axe while he shouts a final slur – suggests a view of race prejudice as simply another moral luxury that the imperatives of the country do not permit. Such is the extent of McCarthy’s social optimism.

Unlike Melville he is little interested in psychology, more concerned with man’s actions and final destiny than with the contours of the mind – even, notoriously, discounting Proust and Henry James as unconcerned with literature’s ultimate questions of life and death. This was something that would favour him in the 1980s and 1990s, in a climate of opinion marked by an assault on Freud’s legacy, one that opted for biological ways of thinking that were better adapted for an age re-equipped with laissez-faire notions of the economic survival of the fittest.

2—“For all our talk of individuality, compassion and subjective truth, we’ve replaced diary-keeping with a practice centred on its opposite.”

The diary, writes Grazie Sophia Christie, used to be where people would write about their inner lives. These volumes – like Virginia Woolf’s – brimmed with confession and regret. But it has been replaced by the journal, a multi-use therapeutic tool. That process tells us something unsettling about the way we live now. WL

Social media is crammed with bullet journals, gratitude journals, manifestation journals, dream journals, prayer journals, therapy journals, but very rarely diaries… Such workbooks take for granted that well-being comes in the form of productivity, or inversely, that productivity makes you well; that darkness is meant to be healed, “processed” but not dwelled upon or, God forbid, relished; that the only acceptable form of egotism is improving yourself; that if productivity, healing and self-improvement are the chief ends, the journal habit is our means of reaching them – and so they can be solved without much nuance, like plugging variables into equations.

These limitations arise from the way contemporary journals are used: as therapeutic tools. Subliminal and subconscious possibilities are eliminated, probably because they can’t be filmed. Woolf’s diaries belong to an earlier tradition, when diaries were literary, but also confided in, confessed to, ranted to, almost like friends.

3—“‘Humanity’ cannot take control of the evolution of AI, because humanity – understood as a collective agent – does not exist.”

John Gray turns his gaze on AI: its inherent momentum, the metaphysical shock of machine consciousness, prospects of catastrophe. These closing paragraphs are still reverberating in my mind. HL

The logic of AI is the progressive displacement of actual experience by mechanical simulacra. Instead of the daily encounters that enable communities to sustain a common life, random collections of solitary people are protected from each other and themselves by unblinking video surveillance. Rather than connecting in troublesome relationships, they are turning to cyber-companions for frictionless friendship and virtual sex. The contingencies of living in a material world are being swapped for an algorithmic dreamtime. The end-point is self-enclosure in the Matrix – a loss of the definitively human experience of living as a fleshly, mortal creature.

A depleted human species may linger on, but AI may still bring an end to the human era. If ever more people opt for a programmed existence in the techno-sphere, the human world will be emptied of meaning. What will be lost are the fugitive sensations of accidental lives – the defiant smile in the face of cruel absurdity, the glance that began a love that changed us forever, a tune it seemed would always be with us, tears in the rain.

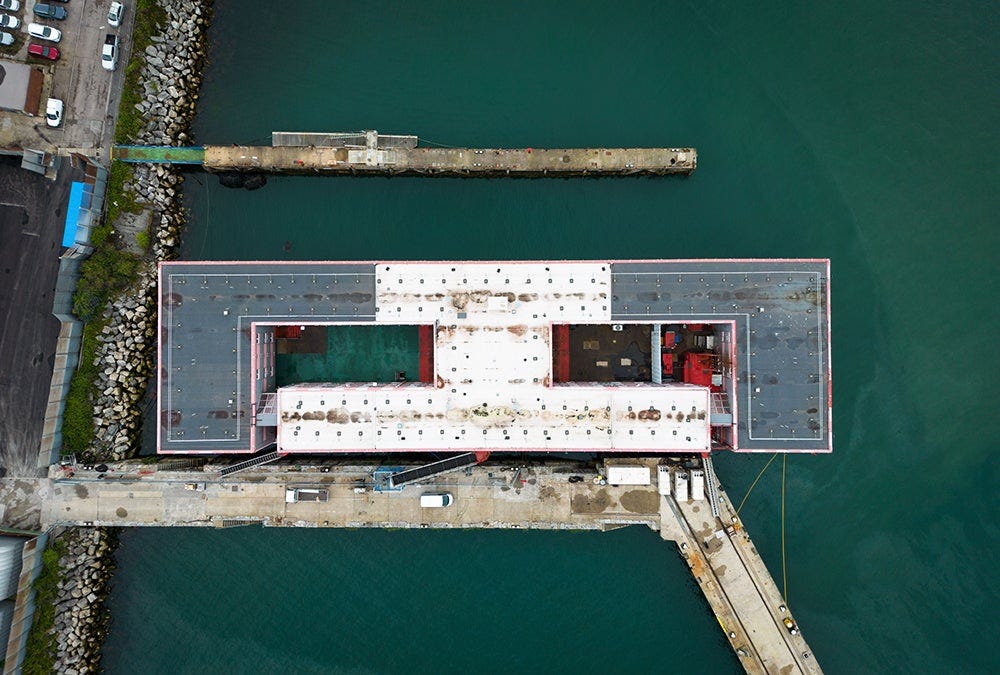

4—“He had a ‘horrible feeling that if something happens, it will be caused by a Brit. The community can self-destruct on its own; this is just ammunition.’”

Anoosh reports from Portland, Dorset where this week the Bibby Stockholm barge received its first tranche of asylum seekers. She speaks to them and to the Portland community, and uncovers a tinderbox. WL

Portland has some of England’s most deprived neighbourhoods. In the last five years the hospital lost its beds and minor injuries unit. Low-wage jobs compel the young to leave. “To people hostile to the refugees,” said Philip Marfleet, a 75-year-old professor from nearby Poole, “we say focus your efforts on the government, which is responsible for running down the local economy, and 30 years of disinterest in the lives of local people.”

Volunteers plan walking tours and cricket matches for the newcomers, and an extra £2m was granted to help Dorset Council step up provision. But I watched two Bibby buses arrive in Weymouth while two local services were cancelled back-to-back, leaving a queue of sweltering pensioners waiting an hour at the same bus stop. A taxi driver told me that if asylum seekers miss the bus, they can call a number that goes through to local firms. “They’re getting everything for free and this is one of the poorest places in the country,” he said. “Drunk idiots might kick off; I told my Indian friend to be careful, in case he’s mistaken for a bargeman.”

How to make IT sustainable

The IT industry has been a significant source of environmental damage, but is now transforming itself. It has responded to the need to develop better sustainable IT, from manufacturing to services to decommissioning. In partnership with Intel vPro.

5—“Brexit is a trade war by the UK on itself.”

This is a good stat-packed interview by George with Adam Posen, the grandee American economist and former member of the Bank of England’s Monetary Policy Committee. Two facts stood out. First, the UK is paying 10 per cent of its tax revenues in debt next year – four times the western European average (in 2009 we paid the same proportion). Second, the US is possibly richer than you realise: it now accounts for 58 per cent of the G7’s GDP, up from 40 per cent in 1990. HL

Posen, who hosted a Q&A with shadow chancellor Rachel Reeves during her recent US visit, is sharply critical of Labour: “I think the priorities are out of whack. I would not be so afraid of being characterised as ‘tax and spend’. I would be looking for places to raise taxes including carbon taxes, wealth and property taxes… I would use that money not to pay down debt but for public investment and to get rid of the two-child benefit limit. I was gobsmacked that any Labour shadow cabinet member would speak in favour of it.”

6—“The accidental coup could well culminate in a regional war involving countries with a population of more than 400 million.”

Bruno Maçães examines why calls for stability in Niger are unlikely to defuse tensions there. In West Africa stability has become a “cursed word”. WL

Stability is unlikely to return to West Africa any time soon, but there is a difference between recent events and those at the time of Sankara in late 1980s Burkina Faso or Jerry John Rawlings in 1990s Ghana. Unless Emmanuel Macron – in a moment of madness – decides to send French special troops to occupy the Presidential Palace in Niamey, this time the great questions about the region’s future will be decided by Africans. There seem to be two sides at the moment. Continuity will be favoured by authorities in Senegal or Nigeria. In Niger and Burkina Faso, the mood is very different. Continuity offers little hope and people like Traoré and many of the young officers in Niger see their future as intimately connected to a new wave of political revolution in Africa.

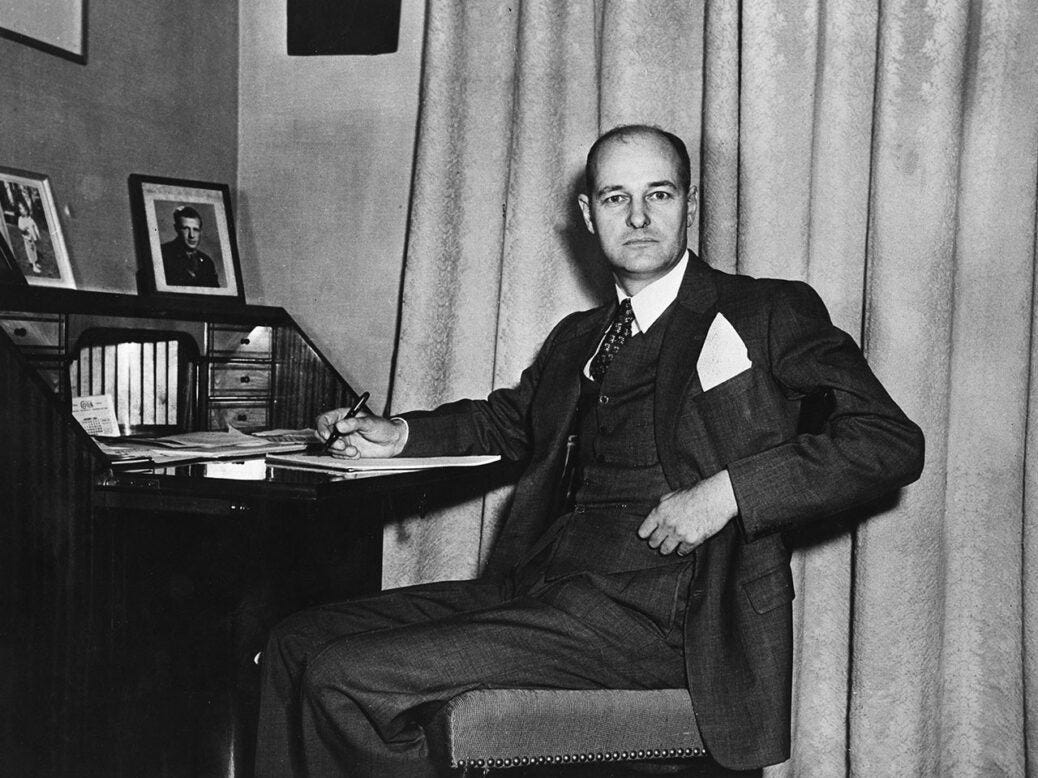

7—“Kennan viewed himself as a loser, an exile of a now-vanished world of reason, the ambassador of an ‘old regime’ that nobody remembers.”

Ivan Krastev and Leonard Benardo dissect George Kennan, the American foreign policy sage – and relic of his age. Featuring a fascinating aside on how Carl Schmitt invoked De Tocqueville to defend himself against charges of Nazism. HL

Schmitt writes of the 19th-century French aristocrat and diplomat: “Every sort of defeat was crystallised in his person, and not just accidentally but as a kind of existential destiny. As an aristocrat, he lost out in the revolution… As a liberal, he anticipated the revolution of 1848 and its divergence from liberalism, and he was cut to the core by the onset of terror he knew it would bring. As a Frenchman, he belonged to a nation that was defeated after twenty years of coalition warfare… As a European, he was again in the role of the defeated since he foresaw the development of two new powers, America, and Russia… that would push Europe to the margins. Finally, as a Christian… he was overwhelmed by the scientific agnosticism of his era.”

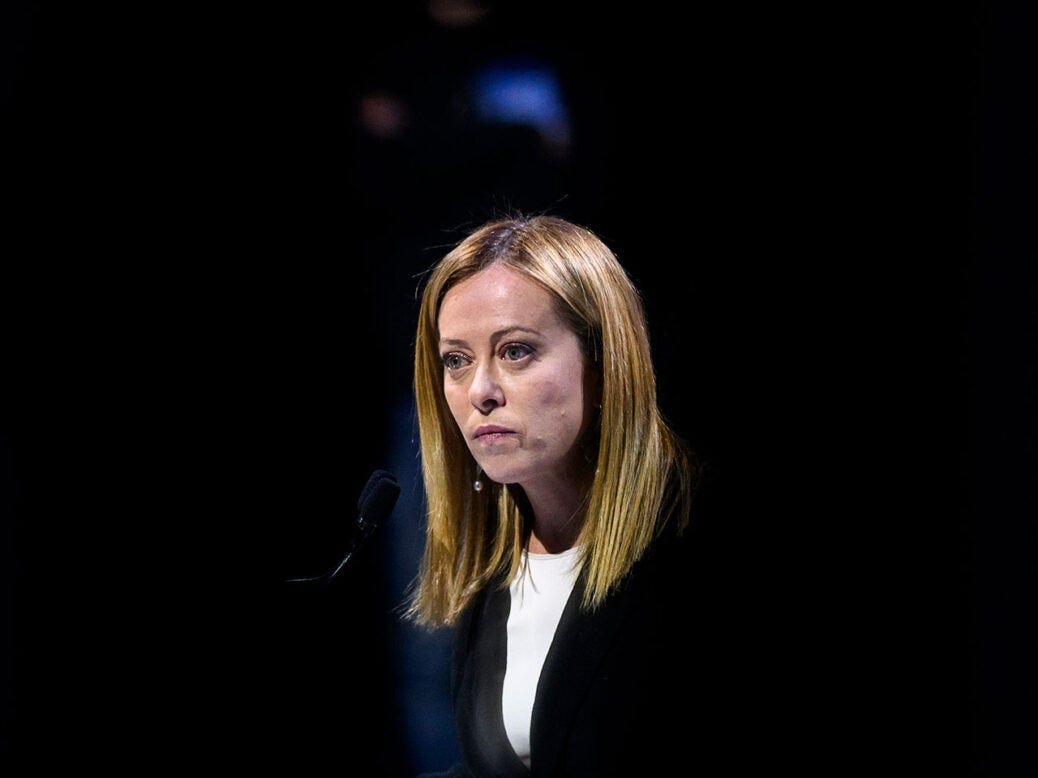

8—“Is this an affront to the banks, a rebuff to neoliberalism, even the harbinger of a clash with Europe?”

Giorgia Meloni announced an eye-catching new windfall tax on banks’ profits last weekend. The move caught many commentators by surprise. They ought not to have been, argues David Broder: the tax is not as radical as it appears. WL

Efforts to paint the government’s economic agenda as “left wing” are wildly misplaced… In reality, Italians at the bottom end of the income scale have more to fear from this government than those at the top. December’s budget announced a phasing out of citizens’ income, an up-to-€780-a-month benefit for low earners and the unemployed that had been introduced in 2019. Meloni’s party has long damned “handouts” to those who “stay on the sofa” rather than find work. In July, 169,000 families received text messages telling them their payments would stop imminently. The government is replacing this with a more restrictive workfare scheme, offering a meagre €350 a month.

Will and Leila’s Best of the Rest

Bloomberg: China’s economy is “ticking time bomb” claims Biden. Is being 81 years old also a ticking time bomb?

Guardian: News Corp’s AI-driven future.

WSJ: No one in Asia wants to make your cheap crap anymore. And who can honestly blame them?

Christine Emba: The ideal man does exist.

Hillary Clinton: Let me cure your loneliness.

Dominic Cummings: My delusions of grandeur. He still has good lines doesn’t he?

Robert Kaplan: The Middle East after empire.

Isaac Wilks: Interrogating the “zoomer question”. A magisterial attempt to understand what makes everyone under 25 so sad.

Eugenics is evil. Sometimes it has to be said.

Elsewhere on the NS

We shouldn’t bank on a Labour victory at the next election, thinks Ben Walker – the data shows that a Tory recovery is still possible.

Meet Liz Truss’s biggest rival since the lettuce that outlived her premiership.

“X” is going well, isn’t it. Elon is now threatening to sue the non-profit Center for Countering Digital Hate. Sarah Manavis reports.

Britain’s reactionary political “centre” has resorted to splitting the world into friend and foe, writes Finn McRedmond. Why has it become so irrational?

Zoe Strimpel went behind the scenes of a Hungarian radical conservative festival. Here’s what she found.

The Japanese asset bubble burst in 1990. Its reputation as one of the world’s enviable economies waned. George Magnus thinks China could face the same fate.

Liam Duffy examines the jihadist roots of the most destructive riots in France’s recent history. They have finished for now – but how long until the violence resumes?

“These methods are hardly Bolshevik. He is no Ken-in.” Lawrence Freedman has written a strategic political and military analysis of Barbie. It’s hilarious.

Here are the summer’s best books, reviewed in short by some of our contributors.

How to get into: Distance running

Each week we ask someone to recommend three books as a way into a subject. This week we turned to Olivia Woosey, who runs SEO here at the NS and just happens to be running the South Downs Way this weekend. That’s only… 100 miles.

The best way to get into distance running is, undoubtedly, to find somewhere with scenic trails; then just put your trainers on and jog along to your heart’s content. Here are three books that may inspire you to do just that. If not, it will offer an insight into the minds of the crazy people that do.

Born to Run by Christopher McDougall (2010). This classic tells of McDougall’s journey to discover the secrets of the Tarahumara tribe, the world’s greatest distance runners. At the same time McDougall delves into the science of running, pointing out that we did not evolve to run on expensive cushioned trainers. Stripping it back and running barefoot could be the key to running further and better.

What I Talk About When I Talk About Running by Haruki Murakami (2009). The novelist started running in the 1980s, and has run regularly ever since (typically six days a week), competing in ultra-marathons and triathlons. This is, in his words, “a kind of memoir that centres on the art of running”. It gives a taste of the mental clarity you can achieve on long-distance runs and why you should run. You can’t force someone to run 26.2 miles – be out there because you enjoy it.

Solo by Jenny Tough (2022). Jenny Tough (yes, real name) documents her incredible journey running solo and unsupported across a mountain range on every continent. As well as an epic adventure, this is a story of personal endurance, self-discovery and challenging perceptions.

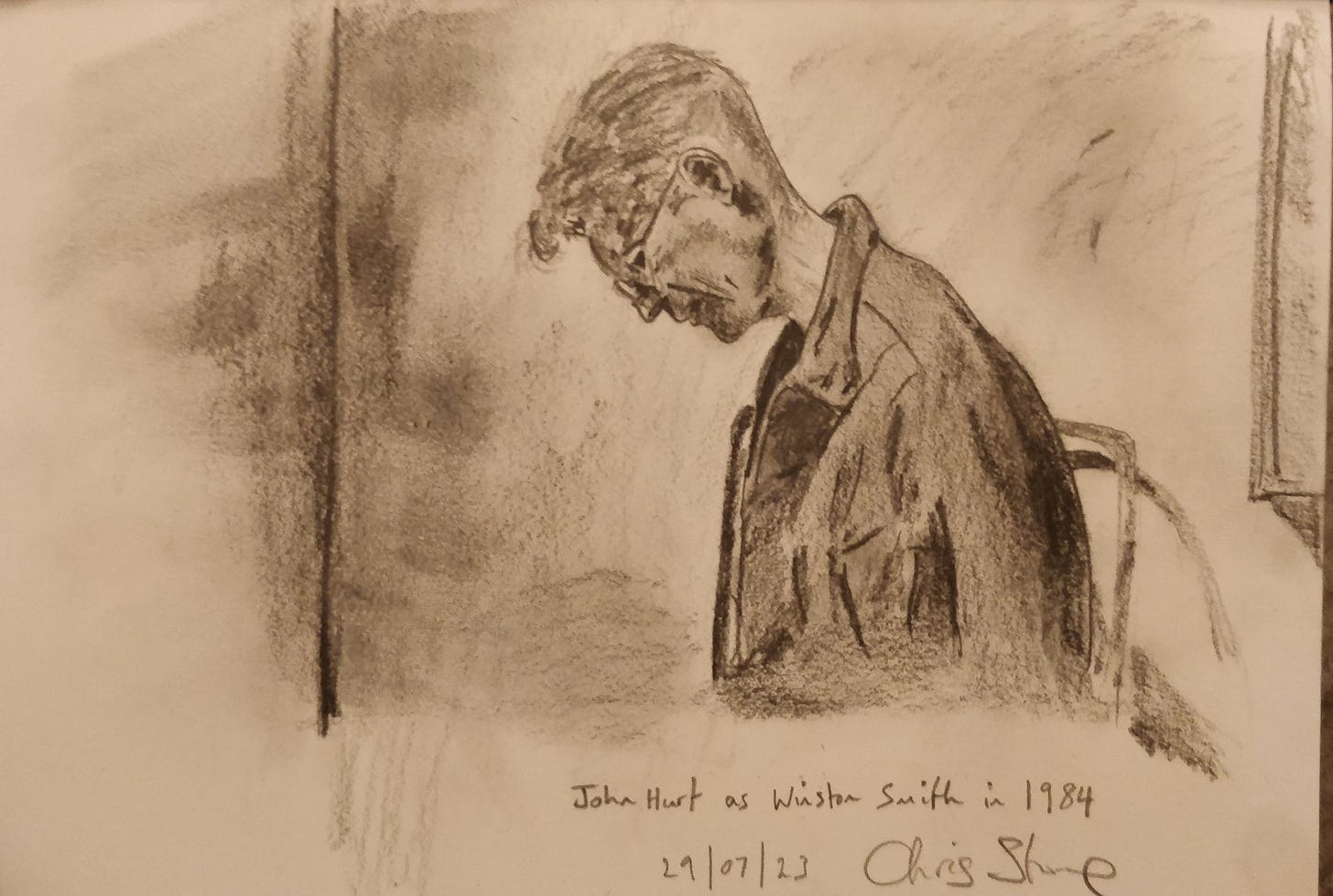

What we’re watching: Nineteen Eighty-Four (1984)

We’re not really watching this film, which I last saw at the BFI some years ago. But I’d like to be. It’s like something out of another world, best seen in a cinema on film, and nothing like movies made today (I’ll stop before I go on). We were inspired to recommend it after Chris Stone, our video and podcast chief at the NS, drew this picture of John Hurt as Winston Smith for fun. HL

Thank you for reading. Don’t miss out – subscribe to the New Statesman and stay up to date with everything you need: from news and analysis to comment and criticism.

Whether you’re looking for a sharp blog or a finely written feature, the New Statesman has you covered. Have a good week, and catch you next Saturday.

Thanks to Barney Horner and Leila Moore.