The Saturday Read: The NS turns 110

Thank you for being a reader of ours. Here are this week's picks.

Good morning, and welcome to the Saturday Read, the New Statesman’s weekly guide to the best writing on ideas, politics, books and culture. This is Harry. This week we are sending you a selection of our essential reads and a handful of other NS articles we think you might like, along with a piece from the past. Best of the Rest will return next week.

This week we turned 110. Do pick up our beautifully designed 110th anniversary special, on newsstands now. It’s full of reflections from New Statesman writers, dating back to the Seventies. Some of those pieces are noted below, but you can enjoy the issue in full here.

Will has written this week’s sign-off. You can get in touch by replying directly to this email. If the pieces below interest you, you could try a trial subscription to the NS. Read three free articles after registering on the New Statesman site. A digital subscription is just 95p a week. Let’s get to it.

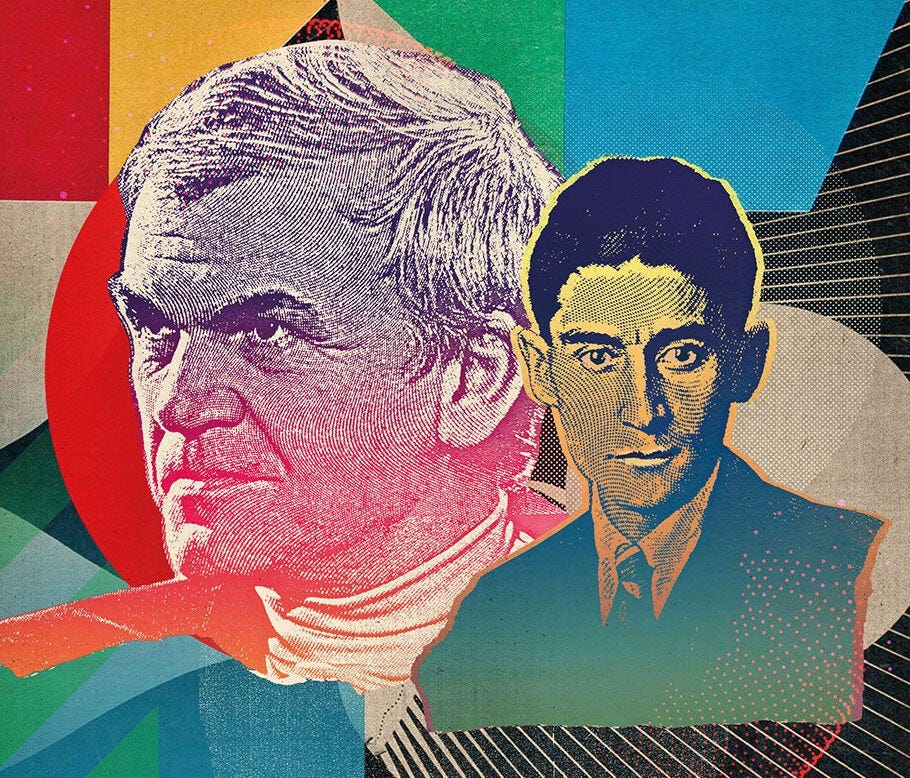

1—“They resented being cut off from a world of which they had been an essential part.”

Writers, Milan Kundera once wrote, should not confine themselves within the boundaries of their culture; the central concerns of literature are generically human. Yet the questions Kundera’s novels pose, John Gray writes, are distinctively those of a generation of authors from central Europe. The default setting of Kundera’s work is the suffocating tyranny that results from the pursuit of world-transforming political projects and the comical attempt to carry on some sort of normal life. His novels are black comedies, brightly staged.

In this extract from a newly published collection of Kundera’s early essays, the writer relates an episode from his past in Soviet-era Czechoslovakia in which the police had seized the only copy of a manuscript written by a philosopher friend of his. Kundera’s friend, as Gray writes, was at a loss:

As they walked on, the two of them came up with a plan. They would make the episode an international scandal by writing to “some figure above politics, someone who stood for an unquestionable moral value, someone universally acknowledged in Europe. In other words, a great cultural figure. But who was this person?” Then they had an epiphany.

“Suddenly we understood that this figure did not exist. To be sure, there were great painters, playwrights and musicians, but they no longer held a privileged place in society as moral authorities that Europe would acknowledge as its spiritual representatives. Culture no longer existed as a realm in which supreme values were enacted.”

In the end they wrote to Sartre, “the last great world cultural figure” in Kundera’s eyes. Who could someone write to now?

2—The Swiss, Faulkner wrote, are “not a people so much as a neat, clean, solvent business”.

Matthew Engel introduces us to Switzerland – that strange silent kingdom without a sole head of state, where the federal parliament sits just 12 weeks a year, and the dream of hyper-local politics lives on. Power is devolved to the country’s 26 cantons, and to the voters, who cast referendum votes half a dozen times a year on national issues.

The rules of a Swiss Sunday are fierce and unique: no laundry, no car washing, no lawn mowing; nearly all shops are closed. The religious roots of this have long since withered but referenda consistently back the status quo. Owners of apartment blocks usually codify their own non-sabbatarian rules: no pets, no music, loud laughter or baths late at night. Sometimes even at lunchtime. Stories of bans on post-10pm toilet-flushing may be urban myths, and the other rules may be just good manners – but here manners are compulsory.

In the countryside, there is more privacy but greater surveillance. “The eyes of a Swiss village are always 20:20,” said Matthew Stevenson, an American travel writer who has lived near Geneva for 30 years. He tells the story of a boy riding a bike through his village at 7.10pm on a summer’s evening. “Go home!” said a passer-by. “You’re late for dinner!” Was it any of his business? Stevenson shrugged: “Every decent Swiss family has dinner at seven.”

3—“Time is out of joint; technological change has outpaced our capacity to understand and regulate it.”

Our editor-in-chief, Jason Cowley, looks back on the past decade in our anniversary issue. The liberal world order has borne many strains in that time. Technology, meanwhile, is advancing ever more rapidly, changing the world in ways we barely understand.

The truth is the world has darkened considerably in the intervening years. War has returned to the continent of Europe and the so-called rules-based liberal order, so celebrated by the Economist and Financial Times, has been revealed to be a chimera. What prevails today is the hard, brutal realities of geopolitics. If the essence of politics, as Machiavelli cynically wrote, is not to be dominated, the war in Ukraine has revealed the world as it is, not as liberals would wish it to be.

4—“That decade of Conservative rule left Britain more unequal and more divided, with sluggish growth and queues at Dover. Still, blue passports.”

Helen Lewis, our deputy editor for much of the 2010s, also writes in this week’s issue. She too has reflected on the decade since our centenary, and has also looked ahead, to the surreal spectacle of American politics heading into the 2024 election.

Since joining the Atlantic, I have been struck by the much greater earnestness of US politics – which teeters on the edge of pure camp. I’ve spent the last six months reporting a profile of Florida’s governor and keen culture warrior Ron DeSantis, who is preparing to challenge Donald Trump for the Republican presidential nomination. DeSantis is notably uncharismatic – he makes Keir Starmer look like Harry Styles – but that hasn’t stopped him releasing adverts of himself dressed as a fighter pilot, posing with pythons, and holding a rally flanked by muscle cars.

Every time I’m at an American political event – DeSantis’s second inauguration featured both howitzer fire and a fly-past – I remember that the highlight of a Lib Dem party conference is… Glee Club. DeSantis spent $100m on re-election in Florida, and ended the race with another $90m in the bank. To put that in perspective, British parliamentary candidates are limited to spending £8,700 plus up to 9p per registered voter in their constituency.

5—“Journalism is like a drug: you can’t give it up.”

Richard Ingrams, a founder and former editor of Private Eye, is no fan of Boris Johnson. He did, however, vote for Brexit, the project that enabled him. Kate Mossman catches up with Ingrams, now 85, in Oxfordshire.

His greatest gripe is that satire has failed the country. “I’m still angry about Boris,” he said. “He got away with it. He should have been absolutely, mercilessly torn apart. Certain images and cartoons and jokes can do terrific harm to politicians. I don’t feel anything like that was ever done to him. There are still people out there who think he’s no worse than the others.”

6—“And yet somehow Franzen, who writes capacious, heart-driven social novels, is just fantastically uncool. Possibly the least cool writer working today.”

Will is no longer wondering what happened to novels. Instead he is now wondering what happened to cool male novelists. The species, he suggests, has gone extinct.

Literary fiction written by men is increasingly irrelevant to the culture at large. I think that is hard to disagree with. Scanning the Granta list I realised (somewhat ignobly) that I recognised only one of the male names. If I – a long-time subscriber to literary journals on both sides of the Atlantic, card-carrying London Library member, Daunt Books tote-bag owner – don’t know who they are then who, their mothers and the editorial board of Granta aside, does?

It is inconceivable that someone in my position, with my interests, would not have known the names Amis, McEwan and Ishiguro when they looked at the Granta list in 1983. The last seven (recently published) novels I’ve read were all written by women, and the last literary novel I can remember buying on the day it was released was – please forgive me – Purity by Jonathan Franzen.

7—“In Logan Roy, Brian Cox and Jesse Armstrong made something different – television’s first truly irredeemable leading man.”

(NB: Spoilers ahead.) Forget the anti-hero, that familiar figure of prestige television through the first 20 years of the 21st century. Logan Roy, the “moral black hole” at the centre of Succession, had no redemptive arc, writes Fergal Kinney. Everyone on the show has existed “in his dark, unfathomable orbit”. The series won’t be able to last long without him, but five episodes watching the actual succession, at last, should be just about right. (Succession airs every Sunday/Monday night, for the uninitiated.)

While other anti-heroes often attain a certain amount of redemption in death, on Logan’s deathbed his own children call him a “monster”, say that there’s “no excuses” for him, and that they “can’t forgive” him. Roman, no stranger to self-deception, attempts to call him a “good man” but has to hand over the phone, repulsed by his own lie. Instead of a human being, Logan is a malevolent market force – “There’s Dad!” as Roman says looking at the sudden dip in Waystar stock.

8—“Lunch would start at 12 and usually still be going at six.”

I loved this nine-strong, 5,000-word conversation between our political writers and editors of the past, featuring Helen, Mehdi Hasan, Patrick Wintour, Steve Richards, Jackie Ashley, Rafael Behr, Stephen Bush and Sarah Baxter, chaired by Andrew Marr.

Steve Richards: My period was the early New Labour period. Ian Hargreaves, the editor, wanted two things that were slightly contradictory. He wanted us to find out what was happening behind the scenes of this project. And he also wanted scoops and exclusives, which pissed off the very people that you needed to get behind the scenes. That was the never-ending dilemma.

The world is transformed from that period when you filed the column, you did an interview, and the following day it would be in the newspapers and followed up by the BBC. It was a rhythm that was recognisable and controllable. All that has changed, and I think for the better. It must be exhausting for the current staff, but I think it is much more exciting.

“The Provisional Government has not the power to remain in office; the Bolsheviks have not quite enough force to turn it out.” (15 December 1917)

Julius West was only 26 when he wrote this piece for us in the weeks after the October Revolution. He filed from Petrograd, the newly renamed city of his birth, St Petersburg. The piece is full of the wry energy of a journalist on the ground, so I thought to share it with you in our anniversary week. It’s one of the earlier pieces of reportage we published. (Will is away this week, reporting on the ground elsewhere.) Lewis died a year later during the Spanish flu pandemic.

All the non-Socialist papers have been stopped, and the Socialist papers which do not support the Bolsheviks are coming out under great difficulties, succumbing one after another. The news published is highly coloured, and there is very little of it, anyway. The public is frankly unable to make head or tail of the whole business. Remember that four armies are supposed to be marching on Petrograd.

First of all there is the Provisional Government, somewhere in the outer suburbs; we can hear its guns occasionally. This is being chased by Bolsheviks coming to help the Lenin Government. This army consists of detachments from the Northern Front and parts of the garrisons of Reval and Narva. Then there are the Germans who, according to current rumour, are landing indiscriminately all over the place. And some time after they all get here, the Cossacks will arrive from the south, under General Kaledin. And we shall all have the time of our lives.

Elsewhere on the NS

In 2015, I used to carry a big golden brick of a phone: Chinese-made, unrecognisable brand name, no internet. I loved it, but it became increasingly impossible to travel or function in the world with it. Yet ‘dumb phones’ are making a comeback, Sarah Manavis writes.

Labour’s recent attack ads have cost Starmer the moral high ground, thinks Andrew Marr.

The age of nationalist hegemony in Scotland may be over, we write in our Leader this week.

Mary Quant, who died this week, opened the world’s first fashion boutique. Deborah Orr interviewed her for the NS in 1990.

“We don’t get a crisis of democracy because capitalism is not working – we get a crisis of democracy because capitalism is working very well on its own terms.” Quinn Slobodian, an author of the moment, is interviewed by Gavin Jacobson, our ideas editor.

“Few works of philosophy have the urgency of Reasons and Persons, which was written with extraordinary speed, driving its author to the brink of collapse and its publisher to despair.”

Danny Kruger, the Tory MP, has not held back in a weekend essay for us. “Nihilism has consumed left-liberalism from within, and now animates the corpse. Old socialist principles like the dignity of labour and the solidarity of the working class, and liberal principles like free speech, tolerance and the value of dissent, have given way to a new social justice orthodoxy which admits no dignity or solidarity and brooks no dissent. Yet because it occupies the lifelike corpse of liberalism, the new orthodoxy attracts the usual bien pensant progressives (including some calling themselves conservatives) who think they are still promoting a diverse and tolerant society.”

“It’s like the Firm, you never get out.” I enjoyed talking to Mehdi Hasan about his time at the NS. (See too: Claire Tomalin, Jemima Khan, Cristina Odone.)

Audio long-read: Confessions of a philosopher

As a philosophy student in the 1980s, Jason Cowley learned more from Brian Magee – and his two BBC series, Men of Ideas (1978) and The Great Philosophers (1987) – than from any seminar or lecture. Magee had an accomplished career, yet when Jason later met Magee in 1997, he was struck by something the philosopher said as he left: “I get the impression that you feel I am lonely and unfulfilled.”

Was he? Eleven years later, Jason went to meet him again.

And with that…

This week I’ve been reading people debate what it means to be “elite”. Matthew Goodwin, part professor, part internet wind-up act, thinks a “new elite” – basically people who read the Guardian and agree with it – control the commanding heights of the British culture industries. The accused, and much of the commentariat, have fallen for the bait.

None of the people in this argument are elite. There is a certain stylised cold-blooded hauteur that comes with that, and none of them have it. The last person who acted that way, in Britain anyway, was Prince Andrew. Prince Philip liked to say his second son was a “natural boss” – robust, arrogant, rude, disruptive. Andrew thought most of the people around him, unless they happened to be Kazakh billionaires he wanted money from, deserved nothing less than his contempt. When he was a British trade envoy, Andrew travelled with an entourage of lackeys, including a valet whose sole responsibility was lugging a 6ft-long ironing board through the lobby of five-star hotels. At Davos, the prince insisted on having a bigger chalet than everyone else.

This did not work out so well for Andrew in the end. But we can see – in his total disregard for the rules, the way he luxuriated in his own position, and the appalling way he treated other people – the outlines of elite psychology. Newspaper columnists, TV presenters, academics and MPs, especially of the Guardian-reading kind, don’t fit in to this category. It’s an expensive way to behave for one thing, and most of them lack the “f— you” money that makes it possible. Elites own assets, they win all the time, and they do not argue about who is an elite on Twitter. The first step to being elite, in fact, is not being on Twitter at all.

Thank you for reading. Don’t miss out – subscribe to the New Statesman and stay up to date with everything you need: from news and analysis to comment and criticism.

Whether you’re looking for a sharp blog or a finely written feature, the New Statesman has you covered. Have a good week, and catch you next Saturday.