The Saturday Read: The seen and the felt

Inside: Van Gogh, Sabrina Carpenter, Donald Trump and the next archbishop of Canterbury.

Good morning. Welcome to the Saturday Read, the New Statesman’s guide to politics, culture, books, and ideas. This is Finn with Nicholas, Pippa, and George.

The gloomy weather at the tail end of this week has reflected the rather gloomy Labour messaging of recent days. “Things can only get worse (before they get better)” seems to be emerging as the motto of this government. But would it kill us to lighten up a bit? As Andrew Marr puts it in our cover story: Keir Starmer needs to “convey his sense of purpose and hope”. But optimism is in short supply: the self-styled grown-ups have entered the room and painted it grey.

From the proverbial to the literal: in the office we have been reflecting on Starmer’s reported decision to remove the portrait of Margaret Thatcher – commissioned by Gordon Brown – out of the unofficially named Thatcher Room in Number 10. Whether it was intended as a statement of aesthetic or ideological intent, you can tell a lot about people from their décor. Boris Johnson allegedly installed a bust of his political hero, the Athenian statesman Pericles, to his own prime ministerial desk. And though Johnson was mocked for his self-conscious philhellenism, there was some unintended narrative coherence here: Pericles presided over (and was ultimately felled by) a great Athenian plague, much as Johnson was presented with the nightmare of Covid. But I suspect the analogy stretches thin at this point. Pericles was an emblem of rhetorical restraint (Plutarch suggests that he abhorred the “buffooneries of mob-oratory”).

With Thatcher’s removal, Starmer should take the chance to aspire for a better analogue than Johnson achieved. For all his capacities in party management and political realism his hero Harold Wilson is fitting. Then again, given the “bad news first” strategy, perhaps Eeyore would work too.

The picks…

We have a great line-up of writers for you this week. Lee Siegel considers Donald Trump’s cognitive decline; Pippa puts the competition to be the next archbishop of Canterbury under a microscope; and, in my top pick of the week, Michael Prodger writes about Van Gogh’s unique command of the canvas. As ever, thanks for reading and have a good weekend. - Finn

1—“A difficult inheritance”

At present, things look grim for Keir Starmer. But, as Andrew Marr contends in this week’s cover, getting grim early was his strategy as Labour leader, and that came good. (You can also read Andrew on another Labour PM, in his review of Tony Blair’s new book.) GM

It’s always light and shade. But on the economy and on law and order, this has been a more brutal blooding than even Starmer, who had to cancel his holiday, can have expected. It’s going to get stormier, and to get through, he needs more persuasive storytelling and more precision around his first Budget; clearer messages for the party about spending priorities; wise caution on legislative radicalism, at least until the criminal justice system is functioning; and, always, a steely concentration on the big picture, rather than passing turbulence.

He got the job because so many millions of Britons feel the state is decaying, incompetent, drifting towards irrelevance. Restoring its authority, internally and internationally, is a noble and difficult task. We know about the social rot. What we don’t know, yet, is how sound, how strong, the Labour state itself will turn out to be.

2—“Trump is beginning to make Biden look like Oscar Wilde”

Lee Siegel delivered our biggest viral hit of the week, read by none other than Stephen King. He poses a very straightforward question: having unseated one ageing, cognitively-declining presidential candidate, should America now turn its attention to the other? NH

The liberal media cried wolf in 2016, and now they are afraid to ring the alarm bells when it is vital to ring them… Having been criticised for questioning Trump’s sanity in 2017, and despite the daily evidence that Trump’s faculties are degenerating, the ferociously partisan liberal press wishes to present itself as dignified and above the fray. Yet what was good for the octogenarian gander with declining faculties but an intact moral centre should be equally good for the septuagenarian gander with declining faculties and a pathologically absent moral centre. The great blessing in life, and the great curse, is that people can get used to just about anything. That inborn tendency is now, with regard to Trump’s unstable mind, a curse.

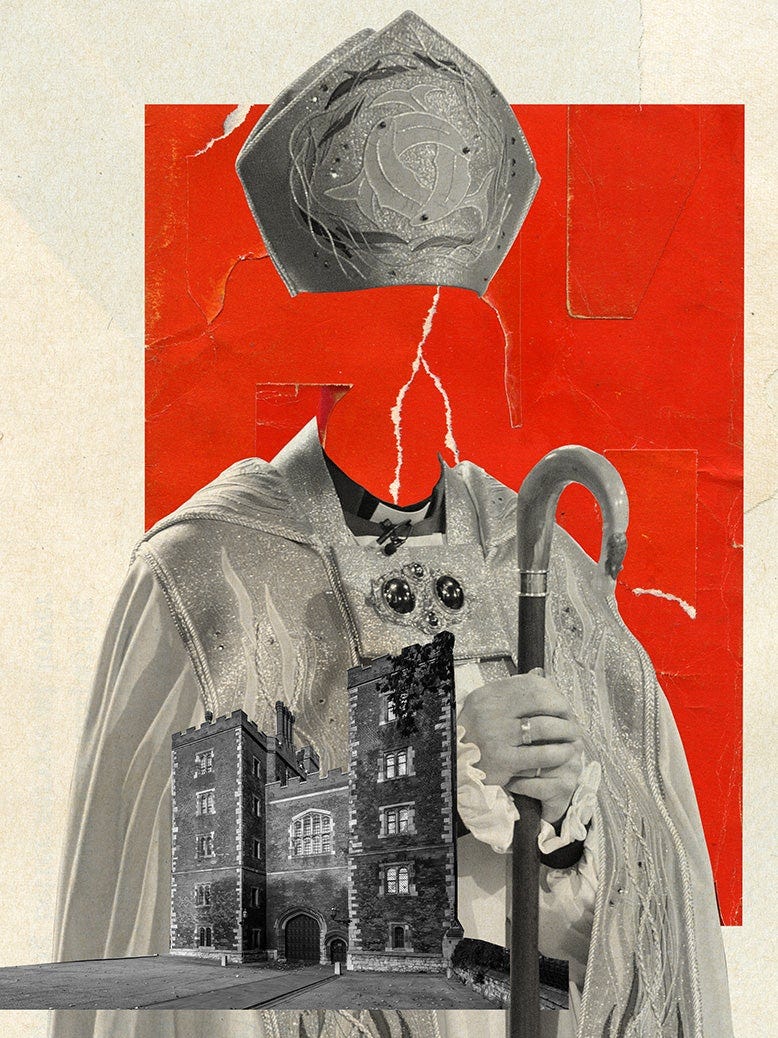

3—“You cannot be seen to want it”

I spent a long time trying to get to the bottom of how exactly the next archbishop of Canterbury will be chosen when Justin Welby retires – and along the way considered some existential questions about the future of the Church of England and asked the experts who they were placing their bets on. PB

The principle of nolo episcopari will once more be quietly and politely on display as Welby approaches the Church’s retirement age of 70 in January 2026 (he could request an extension from the Crown until his 71st birthday if “special circumstances” demanded it, but no previous archbishop of Canterbury has done so). Despite much speculation that Welby would announce his resignation after King Charles III’s coronation last September, the Archbishop appears to be standing by his previously declared intention to complete the longest possible term. If he stays in post until January 2026, he will be the longest serving archbishop of Canterbury since Michael Ramsey, who retired in 1974 having occupied Lambeth Palace for a little over 13 years.

4—“Starmer is a Frankenstein’s creature of class signifiers”

British class hasn’t disappeared, but it has gone underground. Nicholas unearths it. Stop looking for the chaps in Barbours on grouse moors. Downton Abbey has misled you. Look rather for the inconspicuous suit, alighting from an Uber in the City or Temple. That’s your ruler. GM

The public schools and establishment universities might still be producing this elite, but only because they’ve adapted to the new age. Eton Rifles is out, replaced by advanced Stem and kindergarten computer science. And it’s fitting that elite British education is an export industry now, subsidised in particular by the scions of an East Asian super-rich. What they aim to produce is not so much a domestic ruling class but an international elite, fit to fill the rosters of global business. Any descendant of Francis Charteris might pass through the same institutional furnaces as their ancestor, but they’d be smelted and beaten into a very different alloy. These levelling trends are only set to continue. Most people admitted to Who’s Who are around 50. Who knows what the fintech elite of 2054 will list as their hobbies: Peloton and IQ testing?

To enjoy our latest analysis of politics, news and events, in addition to world-class literary and cultural reviews, click here to subscribe to the New Statesman. You'll enjoy all of the New Statesman's online content, ad-free podcasts and invitations to NS events.

On Tuesday I watched an American novel cast for a British stage: The Grapes of Wrath at the National Theatre. You know the story. When their farm fails, the Joad family travels across America in search of work and food. Instead they find exploitation and hunger.

Their 2,000-mile journey is 600 pages in the novel and 170 minutes in this performance. Theatre cannot recreate the characterless vignette chapters Steinbeck called his “generals” – such as a scene of a dust turtle’s death – but compensates with atmosphere. There was a plangent, stirring bluegrass quartet on stage, as well as an actual pool of water which served as shorthand for various rivers.

The first half was dense, but by the second you knew the characters and felt with them. After the famously tricky last scene we filed out in quiet, contemplative moods. It did the novel justice and is entering its last week. There are £10 tickets available, but if you have a free night this week, it would be worth going at the full price too.

5—“Studies of emotional timbres”

Van Gogh was on an endless and troubled quest for an artistic identity. Michael Prodger guides us through his influences – Signac, Seurat, Bernard, Monet – to his eventual destination as one of the most distinctive artists the world has produced. FMcR

He adapted his own way of handling paint, working in dashes, dabs and strokes and almost never with flat, unmodulated surfaces. It unified all his motifs – trees, sky, people, buildings – and made his pictures flicker.

Here is the borderline between the seen and the felt, a liminality he heightened with his compositional method. He would frequently work outdoors but rarely complete pictures there. Almost all would be finished in the studio to allow memory and imagination to act on the real.

6—“The crooked path of progress”

Kenya and Bangladesh tend to be regarded as success stories of the developing world; and yet both were roiled by violent protest this summer. In our weekend essay, Robert D Kaplan reads their trajectories through the work of Samuel P Huntington, mapping their passage through “the great chicanes of history”. NH

Revolts, driven by higher and higher standards for governance, are easy – a mere matter of producing crowd formations. Solving the problems that revolts rally against is much harder. And that’s why the building of order, by way of institutions, is more progressive than even the holding of elections, as Huntington explains… The lag time between revolts and institution-building constitutes the age that these developing societies will inhabit for years to come. “The truly helpless society is not one threatened by revolution but one incapable of it,” Huntington writes. Countries mired in low-level and communal or territorial conflict – and there are a fair number of those – are incapable of modernising revolt. Kenya and Bangladesh are in a more advanced condition. But that is the key to their current instability.

7—“Carpenter is fully of the mainstream”

For those of you who didn’t have Sabrina Carpenter’s ceaselessly catchy Espresso rattling around their heads all summer, Kate Mossman is here to catch you up. This old-fashioned popstar is a refreshing departure from the alternative and indie girls dominating the scene. FMcR

Humour is of great value in pop, and under-employed these days: who didn’t change their view of Ariana Grande – so delicate, so glacial – when they saw the viral clip of her doing perfect impressions of Celine Dion? There were hints that Carpenter was a bit odd on her last, R&B-led album, Emails I Can’t Send, with the trap-style “Nonsense” and its ad lib fade out: “This song catchier than chickenpox is/I bet your house is where my other sock is…” There’s a song on the new album called “Bed Chem” (“Where art thou? Why not uponeth me?”) and in “Slim Pickins” she sings, “Since the good ones are deceased or taken/I’ll just keep on moanin’ and bitchin’,” sounding about 53.

8—“The post-liberal right has crept to the threshold of real power”

How did JD Vance go from delighting liberals by declaring himself “a never Trump guy” to vice-presidential candidate who calls his running mate “America’s last best hope”? Katie Stallard considers the political transformation of the Hillbilly Elegy author, his conversion to Catholicism, and the American new right of which he is a part. PB

The Vance of Hillbilly Elegy seethed with anger at the “learned helplessness” of his community, explaining away the poverty and violence he saw around him with wild generalisations: “We spend our way into the poorhouse… We choose not to work when we should be looking for jobs.” That rage is now directed outwards towards the American political system and liberal democracy as a whole. The Vance of 2016 described in his memoir the growing movement among the “white working class to blame problems on society or the government”; now he is leading the charge. He proudly identifies as a member of the “post-liberal right”, a movement dominated by Catholic thinkers arrayed around the idea that liberalism, with its emphasis on individual rights, is responsible for the myriad social and economic challenges confronting the US, and that the old liberal “regime” supposedly running things must be overthrown.

George’s Best of the Rest

Helen Lewis: Trump’s red-pill podcast tour.

Amy Reading: Editing without ego.

Perry Anderson: Made by the revolution.

Angus Colwell: Is it time to pity restaurant critics? Yeah, and I feel really sorry for waterslide testers.

Hundred respond to Viscountess Hinchingbrooke’s appeal to find duck strangler. Well it’s usually the butler, and she probably has one.

And with that…

When Oasis played at Knebworth in 1996, 2.5 million people (over 4 per cent of the population) applied for tickets. The band were at the peak of their hysterical period of fame – referred to by journalists as the “new Beatles”, featured on the News at Ten, in amongst bulletins on Boris Yeltsin and Bob Dole. Amazing, then, that their reunion gigs almost 30 years later have sparked an even greater fuss, compelling ministerial statements and questions in Parliament. The controversy is over the “dynamic pricing” policy of the Ticketmaster website by which, much like late-night Uber rides, prices were raised in accordance with demand. Fans desperate for tickets were therefore politely mugged of up to £200 more than originally advertised. The band themselves claim this was nothing to do with them and the authorities appear to agree. Ticketmaster now faces an investigation from the sheep dog of British capitalism: the Competition and Markets Authority.

If you fell foul of dynamic pricing, I’m jealous of you. In my own futile search for tickets, I didn’t even get as far as the main queue. Oasis may not be to blame for the exploitation at play here. But they are at heart a populist band who always measured their success by size – overlong songs, “huge” choruses, “massive” arena gigs. The Gallaghers have announced a further two nights at Wembley. If the profit motive is the presiding force at play here, they should surely announce another dozen, the only way of satisfying their pocket-books and the people.

— Nicholas

The New Statesman is home to the finest writing on politics, culture and ideas. To stay up to date, subscribe using the link above.

"Any descendant of Francis Charteris might pass through the same institutional furnaces as their ancestor, but they’d be smelted and beaten into a very different alloy."

I attended an American public school in the early 1970s, Choate Rosemary Hall. I passed through a furnace all right, but instead of emerging as a super alloy I came out squashed for life. Institutionalized emotional neglect on the part of the faculty and administration and a pathologically unfriendly student body broke me.