The Saturday Read: The velvet curtain

Inside: Trump, North Korea, Joe Rogan, Gary Younge on the Blitz, Andrew Marr on Claud Cockburn, and Elvis.

Good morning. Welcome to the Saturday Read, the New Statesman’s guide to politics, culture, books, and ideas. This is Jason, together with Finn, Nicholas, Pippa, and George.

In the late 1970s a divided Labour Party and much of the British left (apart from Martin Jacques’ Marxism Today) misunderstood the forces unlocked by the election of Margaret Thatcher as prime minister. Her victory was complacently assumed to be transient, just another Conservative government passing through, and the consensus politics of the postwar order would be restored in due course.

“When I saw Thatcherism,” the cultural theorist Stuart Hall told the New Statesman in 2012, reflecting on the turbulent politics of the 1980s, “I realised that it wasn’t just an economic programme, but that it had profound cultural roots. Thatcher and [Enoch] Powell were both what Hegel called ‘historical individuals’ – their very politics, their contradictions, instance or concretise in one life or career much wider forces that are in play.”

Something similar could be said of Donald Trump. When he first ran for the presidency as a Republican he was traduced, ridiculed and written off: part orange-faced game-show host, part Mafia Big Man. The American novelist Philip Roth called him the “boastful buffoon”. Trump is boastful and he is a buffoon. But he won in 2016 and may win again next week.

What does he know? What does he understand about the atavistic impulses and insecurities of America and the American people? Why has the Republican Party allowed itself to be captured by Trump and Trumpism? The Maga movement is not a passing phenomenon: like Thatcherism it has hardened into something permanent. It is a counter-hegemonic project. As my colleague Sohrab Ahmari writes in our cover story this week, “The Republicans – once the party of suburban affluence, of free markets and social conservatism – have morphed into a populist vehicle.” There is no turning back.

“No one I know of has foreseen an America like the one we live in today,” Roth said shortly before he died. “No one could have imagined that the 21st-century catastrophe to befall the USA, the most debasing of disasters, would appear not, say, in the terrifying guise of an Orwellian Big Brother but in the ominously ridiculous commedia dell’arte figure of the boastful buffoon.”

But perhaps this outcome could have been imagined. After all, as John Gray has written, the word “populism” has no clear meaning but is “used by liberals to refer to political blowback against the social disruption produced by their own policies”.

The result of the 2024 US presidential election is likely to be decided in Pennsylvania where the polls have Trump and Kamala Harris deadlocked. Trump won the state in 2016 and Biden in 2020. In so many ways, Harris is the ideal candidate for Trump: the West Coast liberal-lawyer with a rictus smile and an undistinguished record as vice-president and an opaque policy platform. She smiles and laughs a lot, but you can see the panic in her eyes. For after Trump comes JD Vance, a true ideologue, and the pro-worker, anti-liberal American New Right.

The picks…

Good morning, Finn here. The Saturday Read has been spending a lot of time looking stateside. And with this tight, high-octane and highly consequential election only days away we hope to bring you the best insight – whether it’s a history of the GOP, a profile of kingmaker Joe Rogan, or a forensic assessment of Kamala Harris’s numbers. But this week we cover all sorts: Gary Younge considers the Blitz and Britain’s national identity; Andrew writes about “the first guerrilla journalist” Claud Cockburn; and Katie contends that Russia’s war is expanding beyond Europe. As ever, thanks for reading and have a great weekend.

1—“Political freakshows.”

In an alternate reality the US might have a European-style political system: a coterie of small parties that reflect distinct interests, rather than the impenetrable Republican-Democrat duopoly. But there’s a lot to be said, Sohrab argues, for a model that forces the two big parties to be flexible and susceptible to realignment. FMcR

Put another way, precisely what appears as the duopoly’s rigidity, the impossibly high bar it imposes on third parties, also makes possible a great deal of flexibility within the two major parties. If there is a genuinely popular political demand “out there” in the electorate, chances are, it will get translated into a governing agenda. The pre-Trump GOP of 2015-16 was a perfect vehicle for the latest realignment precisely because few outside its donor and intellectual circles wanted what it used to offer: futile regime-change wars, entitlement cuts and evangelical moral hectoring. Already in the earlier Tea Party movement there were signs of brewing populist discontent with the GOP mainstream (though those rebellious energies were soon channelled into conventional conservative grooves).

2—“We underestimated Russia.”

Wolfgang Münchau this week writes a lucid – if anxiety-inducing – assessment of the Brics+ alliance and its ever-closer alignment. Neither Trump nor Harris have a strategy to rein in the ambitions of the bloc, he contends. This will have irrevocable consequences for the new “bipolar global order”. FMcR

A related straw man is the observation that Brics+ is not as politically cohesive as the West. This is also simultaneously true and misleading. Member states do not need the same degree of political integration as we have in the G7, Nato or the EU. Unlike China and Russia, India and Brazil are not interested in a confrontation with the US. They want to trade with everyone and not become part of a bloc. Russia, North Korea and Iran have moved closer together. China’s Xi Jinping has formed a strategic alliance with Vladimir Putin, yet keeps a distance. Brics+ is a diverse bunch, but its strength stems from a focus on the few things those nations have in common. The most important one is their desire to reduce their dependency on the US.

3—“Kim Jong Un must scarcely be able to believe his luck.”

Ominous autocratic alliances clarified this week, as North Korea sent 10,000 troops to help Russia at the Ukrainian border. Within hours, South Korea’s president warned that his country would not “sit idle” in the face of provocation. Katie asks whether these escalations are as terrifying as they sound. GM

Beyond the impending battlefield implications, the other danger for Ukraine is that the arrival of North Korea troops fuels the growing narrative among sceptics in the US and Europe that Ukraine cannot win this war, and so further deliveries of military aid will only prolong a hopeless fight. Already facing the prospect of a hard winter ahead, with Russian forces gradually advancing in the east and bombarding Ukraine’s power grid, the country’s president, Volodymyr Zelensky, will come under ever greater pressure in the coming months to show that there is still a feasible path to victory ahead.

4—“Stress-testing Britain’s national identity.”

Steve McQueen’s Blitz, which follows a nine-year-old mixed-race boy who has absconded from an evacuation train, seeks to gently “recalibrate our nostalgia” about the Second World War, writes Gary Younge, stress-testing the idea that it was a time of uncomplicated esprit de corps. PB

Almost 80 years after its end, the Second World War remains central to Western patriotic myths. America has its Greatest Generation and Rosie the Riveter; Russia still refers to it as the Great Patriotic War. The nostalgia inherent in these “narratives” has currency today. (When Ukraine occupied the Russian town of Sudzha this summer the Kremlin was quick to conjure the hurts of the Second World War.) Britain is no different in this regard, which is why Rishi Sunak leaving the D-Day commemoration early became such an issue during the election.

5—“A party with no idea what to say.”

Labour has a language problem – Keir Starmer is devoid of flair, while his cabinet is flippant and ill-disciplined. Finn wonders why the party is frozen around “a core of dead rhetoric”. GM

Starmer stands apart from his predecessors as uniquely indisposed to spinning grand media narratives. Boris Johnson relied on a kind of patrician rizz to bring the country along with him (when the Sun asked him how he unwound at the end of the day he said: “a bit of Greek lyric poetry, nothing complicated”); Gordon Brown struggled in the Treasury but electrified the nation with diatribes against Scottish independence; Tony Blair had a unique ability to introduce phrases into the lexicon (“education, education, education”); David Cameron’s “he was the future once” quip must haunt any ageing parliamentarian.

To enjoy our latest analysis of politics, news and events, in addition to world-class literary and cultural reviews, click here to subscribe to the New Statesman. You'll enjoy all of the New Statesman's online content, ad-free podcasts and invitations to NS events.

Lend us your ears…

A few weeks ago we announced our new podcast Insights – an in-depth interrogation of the key story of the week, and our way of helping listeners understand the forces shaping our unusual times.

Now, we are thrilled to reveal the latest offering in our podcast arsenal: Culture, hosted by Tom Gatti (the New Statesman’s executive editor and literary encyclopaedia). Every Monday, Tom and a coterie of guests will explore a major theme from the world of books, arts and ideas.

This week Tom speaks to Gary Younge and the historian David Edgerton about Steve McQueen’s film Blitz and the ways in which wartime myths have shaped national identity. Set in London during the German bombing campaigns of 1940-41, Blitz paints – as Gary writes in his essay in this week’s magazine – a picture of British society that is divided along the fault lines of class, gender and race. Yet the heroic ideas of “Blitz spirit” and Britain “standing alone” have dominated popular understanding of the war, and have been repeatedly used and abused by today’s politicians. Gary, David and Tom unpick all this and more. You can listen wherever you get your podcasts.

6—“A hero to my generation.”

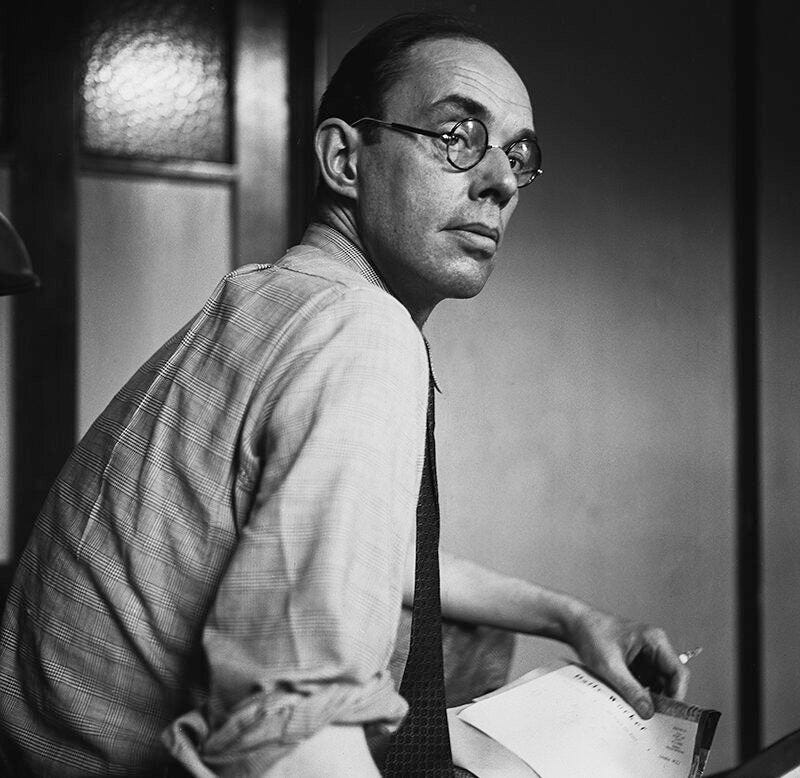

The life of the journalist Claud Cockburn – as told by his son in Believe Nothing Until It Is Officially Denied – bridged the political storms of the 1930s and the early days of Private Eye satire in the 1960s. Such a career, Andrew writes, could only have emerged from the worst decades of the 20th century. PB

During the Spanish Civil War, he behaved at least as bravely as Orwell. Using the nom de plume Frank Pitcairn while writing for the communist Daily Worker, he was very nearly executed by an anarchist column as he tried to get to the front line. Later, as an International Brigader himself, he took part in a suicidal charge against nationalist troops north of Madrid. His physical courage included a willingness to dodge into Nazi Berlin under a false passport, and to return to Hitler’s Germany to help rescue the children of a prominent communist sympathiser.

7—“A sardonic Renaissance man.”

Donald Trump sat down for a free-wheeling three-hour, seven-minute interview on The Joe Rogan Experience podcast last week, which covered the JFK files, White House décor, and the time he told Kim Jong Un to stop building nuclear weapons and “go to the beach”. Freddie argues that the episode could swing the election. PB

Rogan’s politics are eclectic: he has endorsed Bernie Sanders, the “Trumpism without Trump” Republican Ron DeSantis, and has praised the former independent candidate Robert F Kennedy Jr. He is a libertarian who supports gay marriage, recreational drug legalisation, universal healthcare and gun rights. His credulity and openness to new ideas can make him a conduit for unscientific theories. He facilitates debates that others won’t touch: during the pandemic the efficacy of vaccines and lockdowns was a topic on the show. Rogan does not pretend to know more than his guests: he represents his listeners, sharing in their curiosity. He prizes authenticity over everything.

8—“Victims of Elvis’s fame.”

Before she died, Lisa Marie Presley, Elvis Presley’s only child, attempted to compose her memoirs. After she died her daughter completed the task. The resulting book, From Here to the Great Unknown, is “a fast read, but heavy as a velvet curtain”, writes Kate Mossman, an-all American story of riches and grief. PB

There is nothing about the Elvis estate, short of a few mentions of the “Memphis Mafia” who surrounded him in the old days, very little on the music (both his and Lisa Marie’s), and the King is dead by page 62. But it may be the most important Elvis book, because it tells you all you need to know about the legacy of unregulated celebrity: it is a story of generational trauma, ungrieved death, unwieldy projections, superstition and foreboding. The Presley children – Lisa first, then Riley and Ben – lived enmeshed lives with parents they knew were going to die. That precariousness was constantly offset by intense connection, and magical experiences: at least once a week, someone gets a theme park closed down for a private party and the kids ride roller coasters over and over till dawn. For much of the book they’re having the time of their lives.

9—“Brownism with a class-based twist.”

Can you believe we made it this far without mentioning the Budget? But not to worry – George Eaton has us covered. The redistributive statement, he suggests, drew a sharp line between wealth and work, and a sharper line between Rachel Reeves and Gordon Brown. FMcR

Labour’s new emphasis on protecting employees’ “payslips” is designed to sharpen the contrast between work and wealth. The minimum wage, Reeves announced, would be increased by 6.7 per cent to £12.21 an hour and she hailed Labour’s radical expansion of workers’ rights. Combined with the highest public investment since Harold Wilson, this amounts to a clear shift away from New Labour’s political economy.

Though the Chancellor’s team insisted in advance that “the era of rabbits is over”, the Budget contained a few lapine-like creatures. Income tax thresholds will rise in line with inflation from 2028-29, fuel duty will again be frozen and draught beer duty will be cut by 1.7 per cent (knocking a penny off a pint).

George’s Best of the Rest

Michelle Obama: Take our lives seriously

Anton Jäger: Hyperpolitics in America

Martin Wolf: Reeves has made her choice – but success is not guaranteed

Hannah Rowan: So you want to be Joan Didion

Mia Galuppo: Why Hollywood feels so stuck

Ryan Ruby: On the envelope

Jonathan Clarke: Scott Fitzgerald’s last act

Luis Parrales: 30 years of Pulp Fiction looking up

Russian court fines Google $20 decillion, more than global GDP. Can we splitwise this?

After suffering £300k of cheese fraud, dairies overwhelmed with support.

And with that…

Who could see this coming? As though we hadn’t heard enough – as though we hadn’t been repeatedly clobbered over the head with it all summer – “Brat” has just been named the Collins English Dictionary Word of the Year. For those who haven’t been following (and I cannot believe the phenomenon could evade even the most remote hermit) Brat was Charli XCX’s genre-defying and zeitgeist-breaking summer album. But it’s not just that, Brat is an attitude too: a messy rebuff to the puritanical years of clean eating, a manifesto for being a 365-party girl.

But enough of that. This did get us thinking in the office about the strange concept of “Word of the Year”. In a superficial sense it tries to capture the word that entered the mainstream lexicon in the most assertive way. In 2016, Collins opted for the predictable but fair “Brexit”; in 2020 it was “lockdown”. But more often than not the project indulges in ephemeral cant: “climate strike” in 2019 (Greta left school years ago); “permacrisis” in 2022 (maybe if you’re Adam Tooze!). In 2015, the rival dictionary Merriam-Webster opted for “-ism” (?).

But we should not be too priggish, at risk of sounding like William F Buckley’s men standing athwart history, begging it to stop. Stephen Hugh-Jones – founder of the Economist’s Johnson column, on the “use and misuse” of language – had a measured approach to the frenetic churn of our vocabulary. In the “endless debate between… the pedantic view of language and the anyfink goes one… the wise man expects no resolution”. So sure – 2024 was so Brat.

—Finn

The New Statesman is home to the finest writing on politics, culture and ideas. To stay up to date, subscribe using the link above.

"the pro-worker, anti-liberal American New Right"

Which new right is that? Neither Trump or Vance are actually pro-worker in the slightest.

Regarding the Russian invasion of Ukraine, how can your commentators ignore the 600,000 Russian casualties, the bonus payments to recruits which exceed £20,000, the recruitment of mercenary soldiers from Cuba and North Korea, and the excessive concentration on the bombing of civilian targets. Russia is nearer to collapse than Ukraine and, if the foreign mercenaries are like the Romanian troops that the Germans used in the siege of Stalingrad in 1942, they will be sliced through like a hot knife through butter.Putin is hoping for Trump to be elected on 5 November so if that fails to happen, it may trigger a general collapse of Russian morale.