The Saturday Read: This weekend's 8 picks

Inside: Amis, doom, coups, downfall, Freud, Turkey, and the meaning of net migration.

Good morning, and welcome to the Saturday Read, the New Statesman’s weekly guide to the best writing on ideas, politics, books and culture. This is Will. We have a superb selection of reportage, interviews and comment pieces for you this weekend.

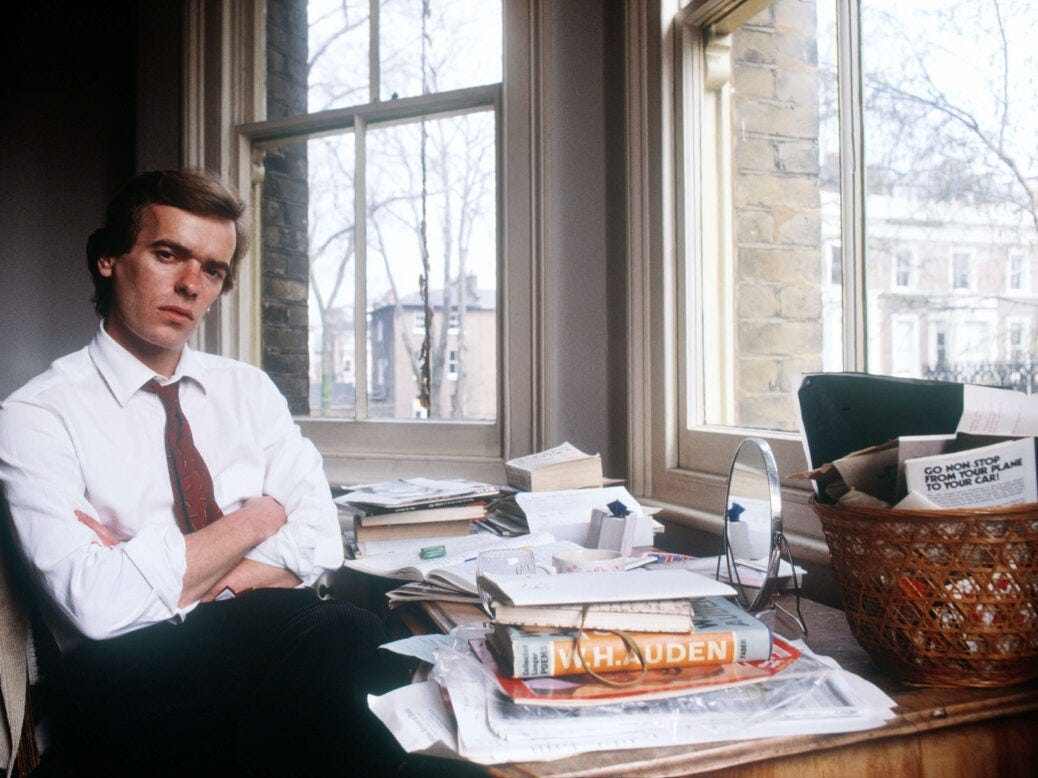

This week I’ve been re-reading Martin Amis. The best of his novels is The Zone of Interest. That was the peak, where comedy and tragedy seamlessly blended. In Money, London Fields and The Information, the comedy is rampant and the tragedy forced. By 2014, when The Zone of Interest was published, and a narrative had taken hold that Amis was no longer relevant, he finally managed to reconcile these two warring elements in his fiction, and make peace with both of them. I would, of course, enjoy finding out what you think is Amis’s best work in the comments. You can find pieces by Tom Gatti and Edward Docx on Amis in today’s edition.

If the pieces below intrigue, perhaps you’d like to try a trial subscription to the NS. Read three free articles after registering on our site. A digital subscription is just 95p a week. Let’s get to it.

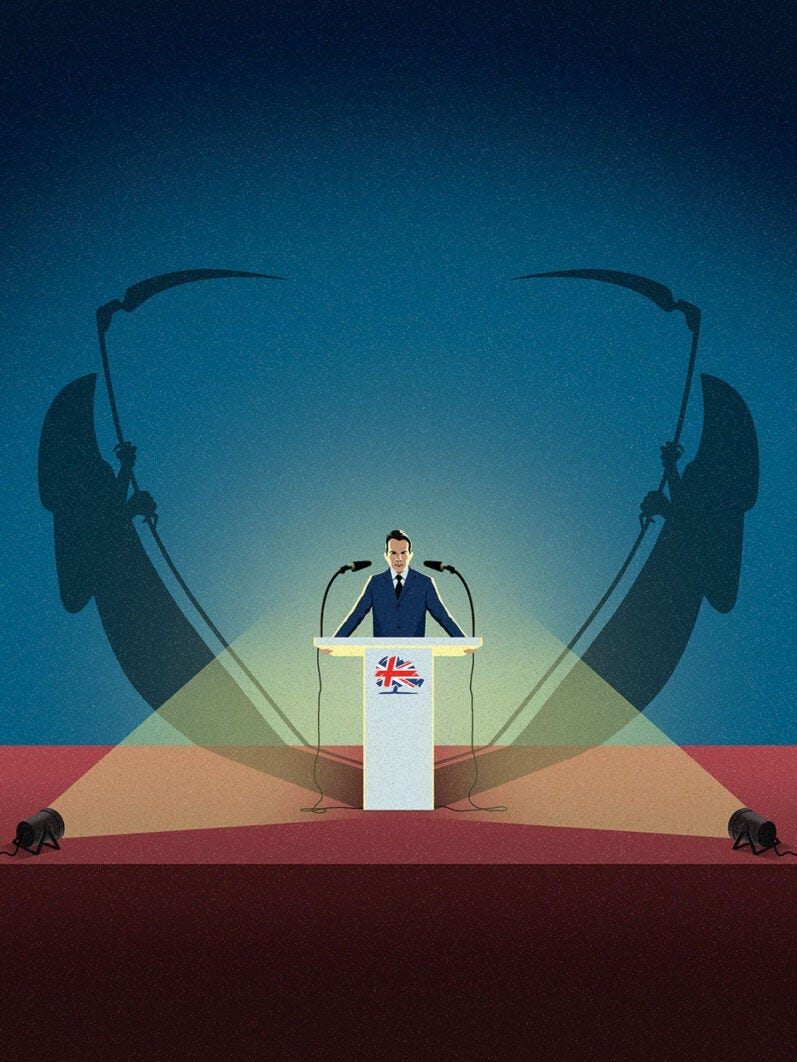

1—“These NatCons dwelled in a catastrophic Houellebecqian universe of malaise and doom.”

Five days. Two fringe political conferences. One Conservative Party at war with itself. The question that hangs over the Tories now, as absurd as it sounds with the next general election at least a year away, is: what comes after Sunak?

Those two conferences, held by the Conservative Democratic Organisation (CDO) in Bournemouth and the National Conservatives in Westminster, may have provided some answers. Bournemouth, where delegates were on an unhappy mission to reinstall Boris Johnson to the leadership of the party, was more fun, if less serious.

For the CDO delegates, the Tory party had become what the EU once was, what the Labour Party and the truculent civil service and the lefty lawyers and the Remainiac judiciary are: a monster to be staked with heroic whines. When CCHQ’s wobbly piñata on the scene, Paul Holmes, the MP for Eastleigh, arrived to take his beating – followed by a weak promise to take the CDO’s literature back to his colleagues on Matthew Parker Street – he left the stage to a lone, strangled scream: “Sunak out!”

2—"Either our people will be in jail, or they will be forced to switch loyalties."

Bruno Maçães has interviewed Imran Khan, the prime minister of Pakistan from 2018 to 2022. In April last year he was felled by a no-confidence vote. In November he survived an assassination attempt. The following May he was arrested on corruption charges. When Bruno, our foreign affairs correspondent, spoke to Khan, he “sounded more pessimistic than ever. I sensed from his words that he sees military rule as practically inevitable, and he believes it could be considerably more brutal than in the past. He told me elections will only be allowed if PTI [Khan’s party] no longer exists.”

Will Pakistan suffer a destructive wave of political violence? Might Khan reach some kind of compromise with the military establishment and return to power after elections later this year? Some might even hope for a refounding of the Pakistani political system, with the influence of the military greatly reduced, which Khan has always refrained from promising, as he may doubt he would be capable of delivering it. Myanmar, Syria or Sudan offer cautionary tales, and they are increasingly mentioned in the Pakistani press.

3—“I didn’t write a word of fiction once I was editor.”

You may have read a number of pieces on Martin Amis this week, but Tom Gatti’s reflection for us – on Amis’s tenure in the late Seventies as our literary editor – is a fascinating read. He has pieced together accounts of Amis from that time, not least by Claire Tomalin, who first commissioned him for the NS (“From the start he liked to put his arm around my waist and hold it there, standing beside me. I liked it too”), and Clive James, who wrote for the magazine in the same era:

I have never heard better talk about the arts and don’t expect to again, but I think all who participated would agree that the thing really took off when traditional fact gave way to current fantasy. Already becoming famous but still retaining enough anonymity to move among other people without their putting on an act, Martin Amis, in conversation, could translate the circumstances of ordinary life into the kind of phantasmagoria that didn’t show up in his novels until later. When he got going, he was like one of those jazz stars, relaxing after hours, who are egged on by the other musicians into chorus after chorus.

4—“The New York Times hired a bunch of lunatics.”

I spoke to Ben Smith, the former founding editor of BuzzFeed News. After BuzzFeed, which is in collapse – the company’s stock has lost 94 per cent of its value in 18 months – Smith joined the New York Times as a star media columnist before starting his own media play, Semafor. But what went wrong at the site whose news division he ran for nine years?

There was a naivety to BuzzFeed. “We had this idea,” Smith said, that people would be sending “their friend a cute picture of a cat, or a link to a fundraiser for an earthquake, or a thoughtful New Statesman piece that made you look like a person who has good values. People wouldn't be out in these public spaces acting like total maniacs, and screaming about the most divisive politics you can imagine. [As actually happened.] That was just a total misread of social platforms and of human nature.”

5—“Everything in here is real.”

Though she is no longer a merry wife of Westminster, Sasha Swire is well-placed to review Cleo Watson’s debut novel, Whips, a sex-farce that nods and winks towards the seamier side of high-politics.

Let me tell you, I know these people and many of them are very much here and present, if a bit jumbled up. This book is the literary equivalent of reading stolen property. We have the politically ambitious wife with a direct line into the top hacks. A “babbling like a f**kwit” education secretary. A female prime minister pulling swords out of her back. An oversexed female cabinet minister (bet you want to know who she is). An ex-serviceman who wants to be prime minister. Politicians’ relations who want gongs. The clever, thrusting Spads, forever obsessing about power: who has it, who wants it, who should have it taken away. And mostly, will they keep theirs?

Aimless ex-prime ministers loiter around menacingly, trying to stay relevant. Or is that something borrowed from the other mob? There is only one glaring and somewhat surprising omission by our author tricoteuse, and that is a Machiavellian chancellor of the Exchequer.

6—“Pod Save the UK’s intro music is a bit like Proust’s madeleines, if Proust hated madeleines.”

A sparkling tirade from Josiah Gogarty on one of the centre-left’s biggest problems: being cringe. Whether it’s podcasters, pop-historians or politicians, ever since 2016 centrists have worked overtime to embarrass themselves.

Centre-left cringe comes with an obsession with the vibes and “values” of politics. The teeth-gnashing hatred of Boris Johnson centred on his deceit, unkemptness and disregard for the dignities of high office. Suited-and-booted Rishi Sunak generates noticeably less hostility, despite him being significantly to the right of Johnson on both economics and culture.

7—"We still don’t know exactly how common male infertility is."

Are falling sperm counts “threatening human survival”? Are we headed for a scenario akin to Children of Men? Sophie McBain reports.

Shanna Swan, a New York-based reproductive epidemiologist, pays special attention to the role played by a class of man-made chemicals known as endocrine disrupters that are ubiquitous in modern life. They were introduced with minimal regulation and safety testing, and are now found in plastics as well as in cosmetics, our food supply – virtually everywhere. Scientists have found that even in remote Greenland, the fat tissue of some polar bears contains PCB, an endocrine-disrupting chemical banned in the UK two decades ago.

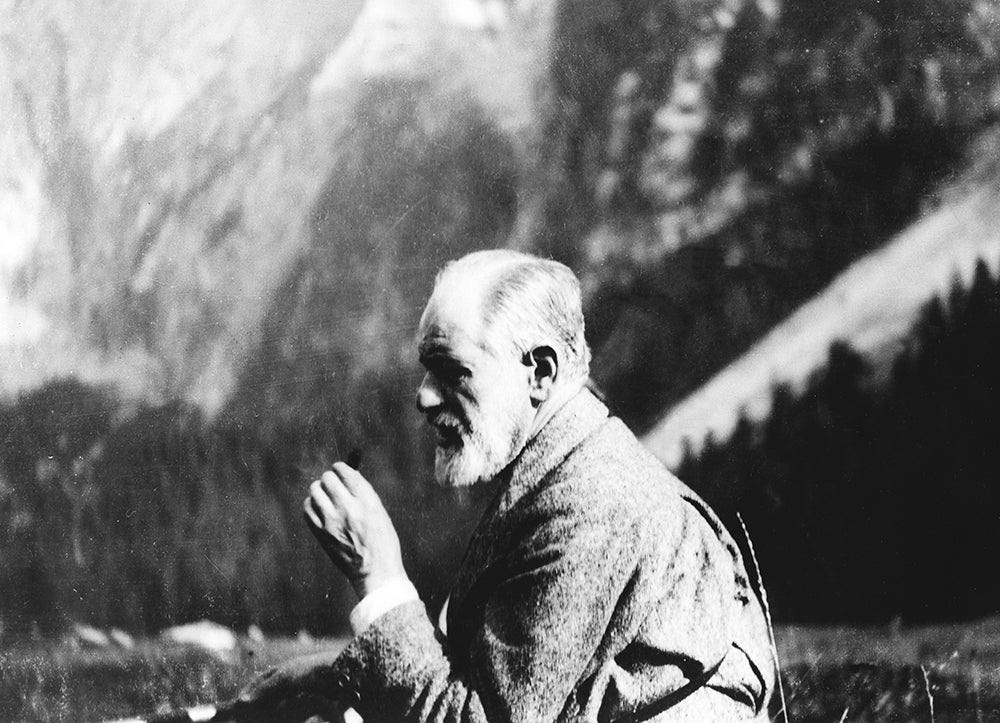

8—“Freud save America.”

Sigmund Freud once described the US as a “giant mistake” – but his opinion never stopped his ideas flourishing on the continent. Psychoanalysis has been in and out of fashion several times in America. Today, it’s back, and in vogue on the left. Nick Burns writes on its resurgence for our Weekend Report.

In intellectual centres such as New York City, psychoanalytic thinking is recruiting new advocates who see in Freud, and in the tradition he inaugurated, something that runs counter to the dominant current in American life – for the better. In magazines, podcasts and intellectual gatherings on the left, an old debate is being carried anew: are the benefits of psychoanalysis limited to the individual, through clinical treatment, or could it have applications to a whole society? Far from plaguing America, could Freud’s legacy offer it a cure?

Best of the Rest

Bloomberg: Europe’s economic engine is broken.

Foreign Policy: Russia’s fascist youth.Tomorrow belongs to Z.

The Nation: There is no difference between DeSantis and Trump.

Axios: Elon Musk moves in on Murdoch. Over nine rounds, my money would still be on Rupert.

Tara Isabella Burton: Why Silicon Valley culture is going woo.

Merve Emre: Susan Sontag’s women.

Hillary Clinton: Biden’s age a ‘legitimate issue’. That’s putting it lightly!

Ian McEwan: Losing Martin Amis.

Becca Rothfeld: Nietzsche’s rules for life. “Don’t shout at horses in Turin.”

“Nightmare living” with Banksy. He sprays, you pay.

Perhaps you might like our daily political email. One in five Saturday Readers subscribe.

Elsewhere on the NS

Kind, generous, attentive – not words always associated with the late Martin Amis. But they really ought to be, if this tribute from Edward Docx is anything to go by.

“Memorial services for friends and colleagues these days come thick and fast. You end up feeling tender and sorrowful for the individual, of course you do, but overwhelmingly f***ed off that they are gone.” Roger Alton writes this week’s Diary.

“Perhaps the only real difference between a feted genius and a brooding sociopath is 11 league titles and two Champions League trophies.” Jonathan Liew suggests Pep Guardiola has, in pursuit of sporting perfection, sacrificed the very things that made him lovable.

Hettie O’Brien delves into the ways in which the elderly and sick are pushed to the margins of British life.

“While the G7 leaders in Hiroshima condemned Putin, it is entirely possible he will be welcomed to New Delhi in September for the G20 summit of the world’s largest economies.” Katie has written on the rise of the non-aligned state.

“Had the UK and the US maintained respect for industry, like Germany and Japan have, politics in Britain and America might have turned out differently.” It's all very well wanting to build things again now, writes Wolfgang Münchau, but why did we let industry wither in the first place?

The future appears to belong to Labour, notes Jonathan Rutherford. “And yet, looking back over the past month, it is Conservatism that has generated energy and held attention.” (Freddie Hayward picked up on a similar theme – “Keir the Conservative” – in Morning Call this week.)

How to get into: Turkey

Each week we ask someone to recommend three books as a way into a subject. This week we turned to Jeremy Cliffe, an NS contributing writer, ahead of Sunday’s presidential run-off in Turkey.

Istanbul: Memories and the City by Orhan Pamuk (2003). A melancholic memoir by the definitive contemporary Istanbul author, published around the dawn of the Erdoğan era about a metropolis caught between West and East, tradition and modernity.

The Island of Missing Trees by Elif Shafak (2021). A story of two lovers – a Turkish Muslim and Greek Christian – that plays out in postcolonial Cyprus and London, by the greatest Turkish author of her generation (and a sometime New Statesman contributor).

Erdoğan’s War: A Strongman’s Struggle at Home and in Syria by Gönül Tol (2022). Key to understanding Erdoğanism is the symbiotic relationship between the president's domestic authoritarianism and regional interventionism. This new work by a leading Turkey expert based in Washington, DC tells that story from its beginnings up to the present day.

And with that…

Six hundred thousand more people moved to the UK last year than left. Net migration from non-EU countries has leapt 154 per cent in 18 months (net migration from the EU is now negative, thanks to Brexit). That uptick has many causes. Compared to June 2021, there are more students (+156,000), Ukrainians (+114,000), arrivals from Hong Kong (+43,000), asylum seekers (+43,000), and more work visas being issued (+74,000), with many healthcare workers among them.

There are also more “dependents” of workers (+67,000) and of students (+65,000). On Tuesday this issue – and the government’s plan to crack down on the right of students to bring dependents with them to the UK – came up when I spoke on a panel. Say dependents and you might think of elderly parents. You’d be wrong: “dependents” are the partners, and occasionally the children, of postgraduate students, and the majority of students (and their partners) leave at the end of their degree. We got into this. It became a tussle.

Net migration is a foolish number to focus on: stay here for 12 months and you’re a long-term migrant. It also leads the media to obsess over a number when the headline figure explains so little by itself. Are students economically beneficial? Are they a drain on resources? If the answers to those questions are yes and no, why is the government trying to cut their numbers just to bring down a figure that has no inherent meaning? (David Goodhart sees this differently.)

Thank you for reading. Don’t miss out – subscribe to the New Statesman and stay up to date with everything you need: from news and analysis to comment and criticism.

Whether you’re looking for a sharp blog or a finely written feature, the New Statesman has you covered. Have a good week, and catch you next Saturday.

Thanks to our colleague Pippa Bailey on this week’s edition.