The Saturday Read: Timbre of the times

Inside: anarchy, Ukraine, the City, woke capital, BLM, and Keir Starmer: football fan.

Good morning, and welcome to the Saturday Read, the New Statesman’s weekly guide to the best writing on ideas, politics, books and culture. This is Harry, along with Will.

This week we spoke to Matthew Yglesias, Washington DC’s pre-eminent blogger, for the latest Saturday Read Conversation. Click through for a ten-minute distilled Q&A on Trump, Biden, ’24, free speech, BLM, the neurotic left, and how politics become symbolic. Will has written today’s sign-off. It’s fairly eccentric.

I have been taking a look at Keir Starmer’s popularity. Reader, it isn’t good. Take Ipsos’s net satisfaction survey for political leaders, which has been running since 1977. Starmer’s average rating since becoming leader three years ago is -9. That is very similar to Neil Kinnock’s (-7) and Ed Miliband’s (-10) over a similar time period. Only Jeremy Corbyn’s ratings (-20) were worse. All three men lost the elections they fought. Starmer has nothing like the favourability of the two opposition leaders who won: Tony Blair (+21) and David Cameron (+3). What do you make of Starmer? Let us know.

If today’s pieces intrigue, perhaps you’d like to try a trial subscription to the NS. Read three free articles after registering on our site. A digital subscription is only 95p a week. Let’s get to it.

1—“The future may not be kind to Nigeria, South Africa and Kenya.”

In the wake of the Niger coup, Robert D Kaplan revisits the prospects for stability in Africa (30 years on from a seminal cover piece of his in the Atlantic on “The Coming Anarchy”). This is a lucid Hobbesian analysis; 3,000 words. Find it in this week’s issue. HL

While Africa is now 18 per cent of the world population, it will rise to 26 per cent by 2050, and is projected to be almost 40 per cent by 2100. At the turn of the 21st century, Europe and Africa had roughly the same population. At the end of this century, there could be seven Africans for every European. While the fate of Europe seems today to lie in the east, in Ukraine, as the century progresses it will increasingly lie in the south, as steady migration from south of the Sahara takes hold.

Niger isn’t critical only because it is a battleground between Russian mercenaries, a cluster of Islamic extremists, and American forces. It is critical because of itself, because its problems constitute a metaphor for some of our most pressing issues. As technology shrinks geography and the world becomes ever more anxious and claustrophobic, so Africa will loom larger in our consciousness as we increasingly comprehend how we are all part of the same human family.

2—“We are living with a 9/11 here every day.”

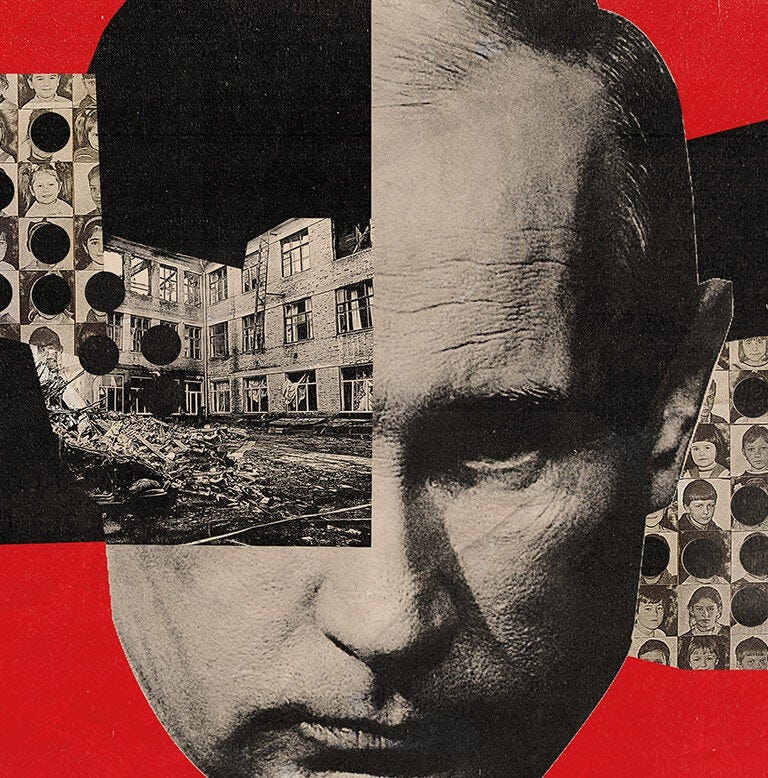

For our cover this week, Katie Stallard reports from Ukraine. Over 3,500 words she gives us the reality on the ground 30km from the line in the crucial eastern stronghold of Kramatorsk, and in the nearby town of Pokrovsk. Vladimir Putin’s focus, Katie shows, has turned to terrorising the Ukraine people. HL

After the missile strike, I messaged Rybinkina to check that she was safe, but got no response. The force of the explosion had ripped chunks of concrete from walls and shattered windows across a ten-block radius in the city. Cars had been crushed in the street. “Putin is trying to scare everyone here,” said Oleksandr, a 60-year-old man in a bright orange shirt who was shovelling broken glass into a bucket outside his block of flats. “He wants to drive people away and divide us. He is trying to destroy our future.”

3—“What Ukrainians can and should do is clear: the remedy for war fatigue is justice in Ukraine.”

Ukraine’s summer offensive has been frustrated. It is time to turn inward, Slavoj Žižek argues quixotically, and for the privileges of the country’s oligarchy to be stripped away. WL

Is there anything more demoralising than to see ordinary Ukrainians fight while many of the rich fled the country and organised for their children to be exempted from military service? A good sign pointing in this direction was the speech Volodymyr Zelensky made on 25 July this year, in which, according to the Financial Times, the president “warned government officials and lawmakers that ‘personal enrichment’ and ‘betrayal’ will not be tolerated, after the arrest of a military recruitment chief on embezzlement charges and an MP accused of collaborating with Russia”.

Yevhen Borysov, head of the military recruitment office in Odesa, was arrested by the State Bureau of Investigation and Prosecutor General’s Office, the newspaper reported. “The National Agency for the Prevention of Corruption said he had illegally acquired more than $5m through elaborate business schemes.”

4—“What ended the independence of the City was the long cultural and political crisis that opened in the middle of the 2010s.”

Travis Aaroe chronicles the rise, fall and death of the freewheeling side of the City of London. There had always been two duelling versions of the Square Mile: obsequious butler-like clerks, and wideboy traders who wanted to make money whatever the cost. After Brexit, the clerks won the day. WL

The City soon found itself conscripted in the defence of this social order. During these years, defenders of the status quo found great comfort in the traditional fixtures of the British ancien régime. Many rallied to institutions like the Speakership of the House of Commons; the House of Lords; the House of Windsor; the “Rolls-Royce” civil service; and Queen’s Counsels.

There was often an aesthetic distaste for these institutions, but it was generally agreed that there was something basically decent and civilised about them. They were Orwell’s scarlet-robed judges who, whatever their flaws, were a bulwark against a greater evil. They represented a hidden cache of “adults in the room”, who would defend civilised standards and the rule of law against the forces of demagoguery.

This attitude drew on a number of sources. One of them was the oeuvre of Stefan Zweig, who recounted how his native Austria-Hungary – crusty, musty, yet more or less benign – was swept away by the darker forces of the 20th century. His memoir, The World of Yesterday – rediscovered and reissued in the mid 2010s – seemed to speak to the timbre of the times.

How to make IT sustainable

The IT industry has been a significant source of environmental damage, but is now transforming itself. It has responded to the need to develop better sustainable IT, from manufacturing to services to decommissioning. In partnership with Intel vPro.

5—“The UK is, for Innocent, an export destination.”

Is Innocent Smoothies as innocent as it seems? Will Dunn reports on the original woke capitalists. HL

Innocent has, since 2013, been wholly owned by the Coca-Cola Company, the world’s largest plastic polluter, and its business is built on the global promotion of what dietitians describe as the “acute consumption of fructose”. The three Innocent founders stepped away at this point and now focus on a venture capital fund, JamJar, that invests in other matey, be-a-good-sort brands: Tony’s Chocolonely, Proper Corn, Oatly, Georgie & Tom’s. Since March 2022 Innocent’s CEO (“chief squeezer” in Innocentese) has been the former Coke executive Nick Canney.

The orange juice comes on a ship from Brazil. Is there any difference between the juice on the boat and the juice in the bottles? At what point does it become Innocent? “Essentially, it gets bottled here,” says Akinluyi… At the same time, a lot of what’s really being made here is plastic bottles, of which Innocent sells millions per year; they are made from 50 per cent recycled plastic, 15 per cent plant-derived plastic and 35 per cent newly extracted fossil fuel.

Like almost every other company selling goods in an oil-based global economy, the world’s favourite little healthy drinks company is a distributor for the world’s petrochemical industry.

6—“That Black Lives Matter was not to be criticised was simply assumed.”

Freddie Hayward interviews Freddie deBoer ahead of his new book: How Elites Ate the Social Justice Movement. Not to be missed. HL

He locates BLM’s failure in elite capture. It was a movement of the elite, by the elite, and for the elite. What started as a noble demand for racial justice became focused on recasting black characters in animation films previously played by actors of other races… Materially comfortable, culture became their political outlet.

The Democratic Party has experienced a similar elite take-over, deBoer argues. “You have an intellectual class, within liberalism, within the Democratic Party, full of people who have never suffered,” deBoer said. “When that’s true… politics becomes a virtue contest. Politics is completely immaterial to [a member of the elite]. You will not suffer if a Republican goes into the White House. It won’t make a difference to you if they cut Medicaid, because you don’t need to be on Medicaid. It won’t make a difference to you if they cut food stamps, because you don’t need food stamps. So politics is permanently immaterial. That is the perfect breeding ground for the kind of politics where you say: ‘if they serve bánh mì in the college cafeteria that’s cultural appropriation’.”

Freddie writes our weekday political email, Morning Call:

7—“The UK is now, statistically speaking, one of the least religious countries in the world.”

What kinds of faith flourish in a faithless age? Jessica Rawnsley investigates the witchcraft practices filling the vacuum left by Christianity’s decline in Britain and America. As a line often attributed to GK Chesterton puts it: “When men stop believing in God they don’t believe in nothing; they believe in anything.” WL

Witchcraft is one form of alternative spirituality in the ascendant: #witchtok has more than 45 billion views on TikTok. Witch influencers proliferate on social media. Eight million #witchcraft Instagram posts detail the how, what and when of magic: moon rituals, hexes, tarot cards, herbal potions, spells. Reddit pages such as r/witch (101,000 members) and r/witchcraft (383,000) garner hundreds of sincere comments each day. Advice is sought and given: how-tos on friendship spells, drying herbs, charging crystals, candle divination. What was for centuries fringe and at times heretical is becoming accepted, even revered, particularly among the young.

8—“At one point Starmer becomes lyrical about the smell of grass, something nobody has ever experienced at a Premier League football match.”

England’s Lionesses are in tomorrow’s World Cup final. As they advanced this week, Clive Martin tried to make sense of the failure of British politicians to talk about the game as if they actually watch it. There is no stranger case than Keir Starmer himself. WL

What’s even stranger is that Starmer is apparently a bona fide football fanatic, a long-term season ticket holder spotted at games well before his ascension to the Labour leadership, as well as a self-proclaimed five-a-side obsessive and “box-to-box midfield general” (according to his official Labour Party bio). This is a man who most likely knows his Ødegaard from his Right Guard, yet he seems to be holding something back. He goes to games, plays several times a week, is regularly spotted with “young gooners” in north London pubs (according to one WhatsApp group I’m in), yet talks about the subject with all the ineptitude of a US president being asked a throwaway question about the “soccer” World Cup.

To his critics, Starmer’s wariness around real football discourse reflects his political persona: evasive, circumspect and probably run through an expensive focus group. After the Arsenal video was released, many pointed to his appearance on the popular Football Clichés podcast, where he listed “goals” and “football” (that’s football, in and of itself) as his favourite things about the game. Which makes about as much sense as saying your favourite thing about parliament is “politics”.

Will’s Best of the Rest

Times: Crooked House pub destruction linked to drug smuggler. Who could have predicted this?

Guardian: Names of Trump jurors posted on right-wing websites.

Bloomberg: British Muslims furious about debanking. It’s not just a problem for populists.

Adrian Wooldridge: The return of the British seaside. See you in Margate.

David Brooks: America is too mean.

Parul Sehgal: Jacqueline Rose puts you on the couch.

Janan Ganesh: The West has forgotten the limits of government.

John Jeremiah Sullivan: Plumbing, the depths. The essay of the year so far.

Bonnie Prince Charlie was an uggo. If he had been 10 per cent better looking the Jacobites would have won.

Pippa’s Elsewhere on the NS

The Tories are providing us with a helpful lesson, says Ben Walker: how to lose an election.

David Gauke sees no good argument for leaving the ECHR. Former party colleagues of his have renewed their siren calls.

Pippa Bailey reviews a memoir about growing up in the shadow of the Yorkshire Ripper (and recalls growing up in the shadow of a much cooler younger brother).

Rachel Cooke on the “steaming dollop of faux-feminist puerility” that is Henpocalypse. Let there be dildos!

Our critic thought Jordan Peterson’s Beyond Order read like a “compendium of stodgy Sunday sermons”. How, then, did the publishers turn Johanna Thomas-Corr’s review into a glowing quote for the paperback?

Revisit Michael Parkinson’s last interview, with the New Statesman’s Kate Mossman.

Phil Tinline takes a walk through John le Carré’s decaying London – and finds it sanitised by money.

Sorry Elizabeth Day, it’s misguided to fetishise failure, Josh Mcloughlin writes.

The generation gap has always existed, argues Jonn Elledge: the internet just made it visible to all.

Disobedience, says Megan Nolan, has a profound appeal for Irish women.

How to get into: Artificial Intelligence

Each week we ask someone to recommend three books as a way into a subject. This week we turned to John Gray – who has been writing for the New Statesman since 1996 – for his recommendations on understanding AI, ahead of his upcoming book, The New Leviathans: Thoughts After Liberalism (Allen Lane), out on 7 September. We’ll be running a Saturday Read Conversation with John soon.

Novacene: The Coming Age of Hyperintelligence by James Lovelock (2019): The late James Lovelock’s last book, published to coincide with his 100th birthday in 2019, is one of his most visionary. He sees the next stage of Gaian evolution as the end of the Anthropocene, in which hyper-intelligent beings will take over from humans in caring for the Earth. He is sanguine as to their attitude to humans. In a whimsical aside, he suggests these superfast digital minds may view us as we do flowers, as low-moving objects of aesthetic interest: “After all, people go to Kew Gardens to watch the plants.”

Turing’s Cathedral: The Origins of the Digital Universe by George Dyson (2012): A companion volume to Dyson’s brilliant Darwin Among the Machines (1997), and one of the best accounts of how a group of mathematicians and engineers at the Institute for Advanced Study in Princeton in 1945 began the process of building what Alan Turing had described as a “universal machine”.

Machine Dreams: Economics Becomes Cyborg Science by Philip Mirowksi (2001): A mind-opening and neglected study of how modern mathematical economics emerged along with cyber-science in the crucibles of the Second World War and the Cold War. As Mirowski tells it, the project of making thinking machines had a decisive impact on economics, the most quantified of the social sciences – and perhaps the most misleading in its view of human nature.

And with that…

On Tuesday, tucked away in a restaurant between Russell Square and Holborn, I had lunch with the food writer Fuchsia Dunlop. We were eating at Master Wei, a Xi’an place, run by the noodle specialist Wei Guirong. When I was younger, Chinese food meant heavy, starchy sauces and “pancake rolls”: the bastardised Cantonese cookery that the British both loved and rather disdained.

Fuchsia, whose successive books on Chinese cuisine have been described as “among the very best, greatest books of the entire millennium”, did the ordering. Smacked cucumber, boneless chicken in ginger sauce, wood ear mushrooms with coriander, pork and seaweed potsticker dumplings, liangpi noodles… We had to move to a bigger table. Fuchsia photographed the dishes; I ate them. My job is demanding at times. The slivers of pig ear in a punchy orange sauce were the revelation. They looked like satellite photos of Jupiter.

I was last served pig off-cuts in a restaurant in Germany. The chefs seemed to have ripped off a pig’s leg and stuck it in an oven. A ridiculous wig of boiled cabbage sat atop it. This image of these two quite disparate pig dishes struck me as a more convincing explanation for the rise of China and decline of Europe than anything I have read. World power is served on a plate.

Thank you for reading. Don’t miss out – subscribe to the New Statesman and stay up to date with everything you need: from news and analysis to comment and criticism.

Whether you’re looking for a sharp blog or a finely written feature, the New Statesman has you covered. Have a good week, and catch you next Saturday.

Thanks to Chris Bourn and Pippa Bailey.

No principles, full of vanity and emptiness. Stands for nothing. No friend of the real Labour movement - and was unnecessarily spiteful to Corbyn and the left. I wish I could have a Labour Party to vote for, but not under Starmer.

I believe a leader’s popularity is linked to his or hers party policies. As yet the public do not understand what Sir K stands for? I for one, earnestly hope that labour learn from the mistakes of Neal Kinnock’s election campaign . Clear direction on policy first, popularity is a bonus.