The Saturday Read: Too strange, too powerful

Inside: Evelyn Waugh, corruption, failed books, a new Lear and America's number one.

Good morning, and welcome to the Saturday Read, the New Statesman’s weekly guide to the best writing on ideas, politics, books and culture. This is Will, along with Harry.

This week we mourn the death of Yevgeny Prigozhin, a fearsome warrior, a leader from the front, and, by all accounts, a wonderful chef. (I jest: the real story about the war right now has little to do with Prigozhin, and more to do with reports of behind-closed-doors clashes between Ukrainian and American officials.) Harry has written the sign-off this week. It’s about a song that I’m not entirely sure he understands the meaning of.

If today’s pieces intrigue, perhaps you’d like to try a trial subscription to the NS. Read three free articles after registering on our site. A digital subscription is only 95p a week. Let’s get to it.

1—“After all, she says, it’s all part of the Lord’s plan, and He does not test us more than we can bear.”

Here’s our 6,800-word cover story this week, by Pippa, in case you missed it on Wednesday. Read this to step into a fascinating and unnerving world. HL

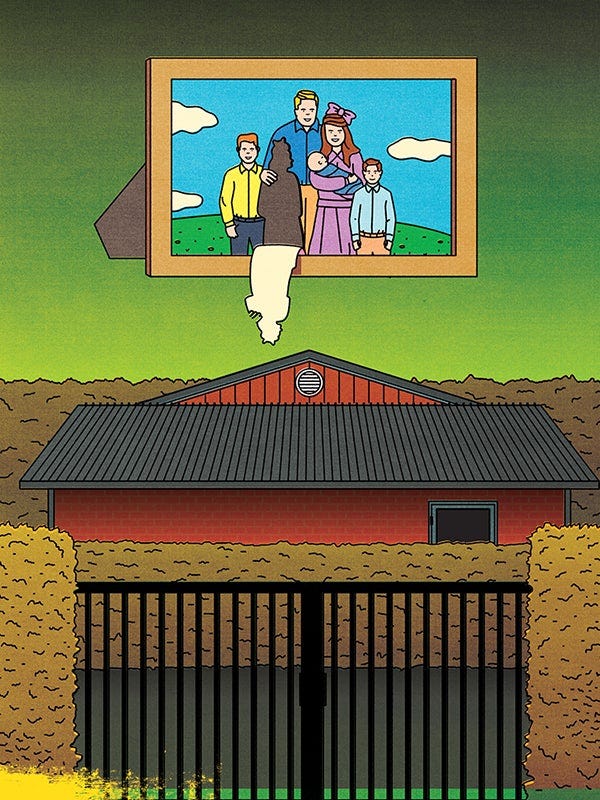

To some, life in the Brethren might seem a conservative idyll. The family unit and the raising of children are central. The divorce rate is negligible, and children live at home until they are married. Homosexuality is not permitted, nor is abortion (as is the case in many Christian denominations); most members use natural methods of contraception. Private education and healthcare are provided. The elderly are cared for at home; poverty is rare. It is unusual for women to work after marriage, and for men, well-paid employment is almost guaranteed in Brethren-run businesses. The Church provides financial assistance to young members to buy homes.

But governing all this is what the Brethren call the “doctrine of separation”. For nearly 200 years members have lived by a literal interpretation of Bible verses such as 2 Timothy 2.19 (“Let everyone who names the name of the Lord withdraw from iniquity”), dividing themselves from the perceived evil of the world. Outsiders are known as “worldlies”. At its most extreme, separation means that when a member leaves or is “withdrawn from” (excommunicated), those who remain will not eat, speak or live with them.

Family may be central, but a willingness to sever all earthly ties is a test of faith. It happened to Thompson’s family – and, many decades ago, to mine.

2—“Waugh remains utterly modern.”

Will has written, apropos of nothing, a marvellous rumination on Evelyn Waugh. HL

In fact, the more time you spend with Waugh the stranger his reputation seems. Today he is one of those widely read novelists who only appears laden with disclaimers. Pinch your nose before you enter his sty. We must dissociate ourselves from his bigotry and snobbery, his cruelty and his love for the aristocracy; we must approach him, Nicholas Lezard wrote in the Guardian, as “we might an ogre”.

Yet there he is, the misogynist, whose closest friends and confidants were all women. There he is, the xenophobe, whose novel Black Mischief (1932) adds up to a rattling takedown of white supremacy in Africa. True, he was cruel, but Waugh was mean for amusement’s sake. The aim was to generate mirth, not maim people. His son Auberon said he “lived for jokes”. And what appears to be a bewildering admiration for the aristocracy is its opposite. Read in sequence the major novels are an excruciating portrayal of the English upper-classes between the wars. Their insularity breeds false confidence, their decadence numbs them to reality, and their amorality makes them callous. Waugh may have loved their world – country houses, fat cigars, St James’s clubs – but he was not deceived about how feckless the upper-classes really were. He spent decades aping their mannerisms while digging their graves.

3—“England is full of rotting boroughs.”

And few are more rotten than Thurrock, where Anoosh went for our Weekend Report. Thurrock council is £1.5bn in debt. How did that happen? Anoosh tells the story of a wild deal gone wrong. WL

From 2016 officials at the Conservative-run council gambled £655m on a renewable energy firm run by the businessman Liam Kavanagh. Instead of investing all this money in his solar farms, however, Kavanagh used millions to buy a private jet, a luxury yacht, a diamond-encrusted Hublot watch, a £2.3m Bugatti supercar and a 232-acre country estate, according to a Bureau of Investigative Journalism investigation published at the end of July.

Investments totalling £130m are still missing – nearly the equivalent of the council’s entire yearly budget. Kavanagh’s lawyers were asked to comment, but did not respond before publication. They told the BIJ that he “never misled Thurrock council during the course of those investments”, and that the council didn’t restrict how Kavanagh could spend the money.

4—“There are more holes in Runciman’s historical narrative than on a mini-golf course.”

Oliver Eagleton examines a new platitudinous work from David Runciman, and and calls into question the academic’s lofty perspective on politics. HL

David Runciman… is best known as co-host of the popular podcast Talking Politics, which ran from 2016 until March of last year. There he reflected on current affairs in his reassuring Eton baritone: parsing the headlines, never taking too strident a position, throwing softball questions to his guests, and recycling conventional north London wisdom on Brexit, Boris Johnson, Donald Trump, Covid. Meanwhile, in its companion History of Ideas series, the don synopsised the work of canonical thinkers through the ages, providing bite-sized summaries of Hobbes or Hayek that one could digest on one’s morning jog.

All this made for easy listening. It promised analysis that transcended the daily news cycle yet demanded no extra mental effort. Reading Runciman, however, is a somewhat different experience. On the page, his chatty, impressionistic style betrays a lack of intellectual rigour. His attempts to affect nuance (“On the one hand… On the other…”) come across as evasive. And his lordly tone – staying coolly detached when discussing war, inequality or climate breakdown – sounds less like critical distance and more like political quietism.

How to make IT sustainable

The IT industry has been a significant source of environmental damage, but is now transforming itself. It has responded to the need to develop better sustainable IT, from manufacturing to services to decommissioning. In partnership with Intel vPro.

5—“She may have wanted to write a historical novel, but the sentences within don’t altogether convince me that she wanted to write this one.”

Lola Seaton takes the measure of Zadie Smith’s new novel, The Fraud. All of Smith’s novels, suggests Seaton, “are in part novels of ideas, where the ideas in question are ideas about novels”. On this evidence, it sounds like The Fraud was a bad novel, and perhaps a bad idea. WL

A recent essay Smith wrote for the New Yorker promising to explain “Why I wrote a historical novel” mostly explains why she didn’t want to, and for a long time avoided doing so. She claims that when she stumbled across the Tichborne story in 2012, she “knew at once” that “it had my name all over it” and would be “perfect for my purposes”, but then put off turning it into fiction for nearly a decade. What were Smith’s “purposes”? She succumbed to the genre, perhaps, not unlike her protagonist, out of an allegiance to the idea.

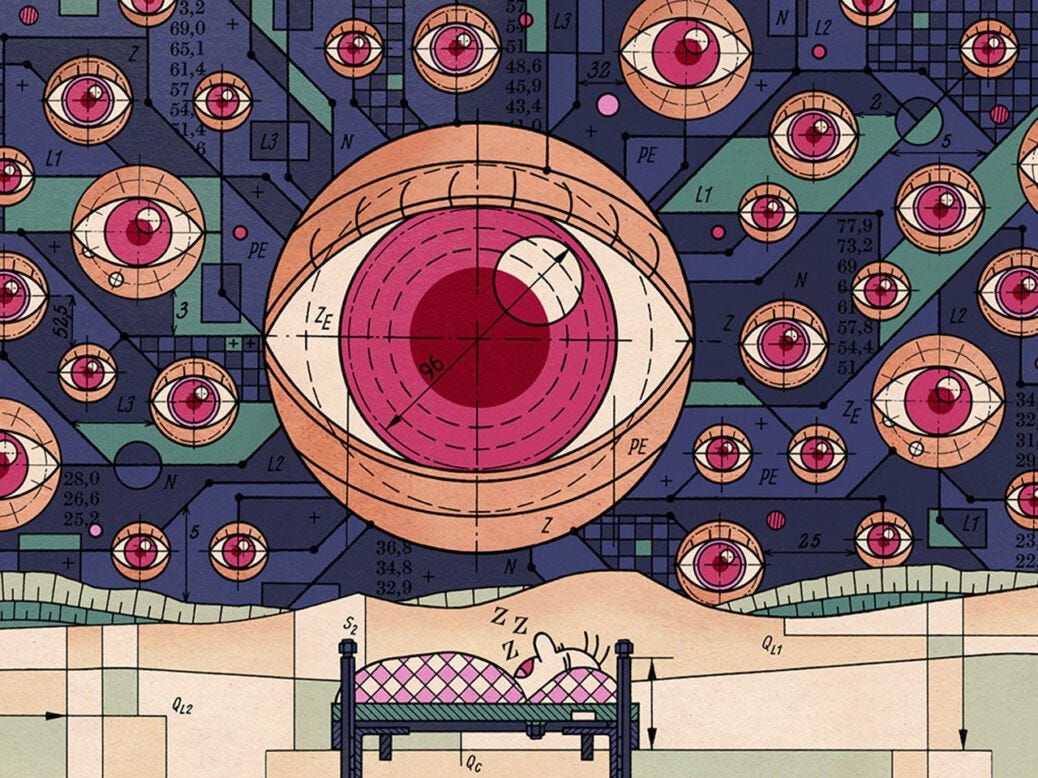

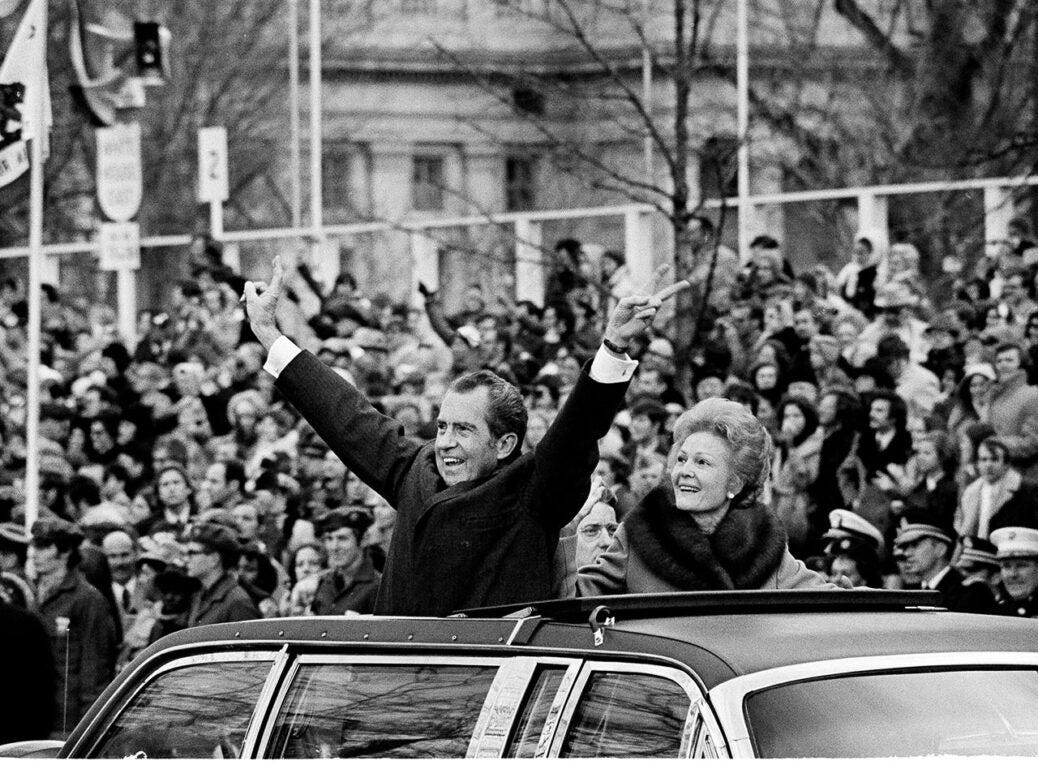

6—“1973 was the year the West never recovered from.”

What if the Western world ended in 1973? It’s a question so out there it’s almost not worth asking it – almost. Alex Hochuli explains how five decades of economic stagnation have warped politics and economics in nations that used to believe they were “developed”. WL

A return to the postwar settlement is now impossible. It was a historically unique arrangement. High growth emerged because of the destruction of capital in the Second World War, with the world economy growing 5 per cent a year from 1951 to 1973. That figure now hovers around 3 per cent at best. On a per capita basis, it is down to 1.5 per cent a year.

The Western postwar political consensus, when the working classes were given confidence by low unemployment and the spread of consumer durables, and elites were disciplined by the experience of war and the threat of revolution, no longer exists. To bring those arrangements back would require another war of the same scale. Viewing that period as a baseline of what the West “should be like” is a grave mistake. Those that do so, on both the left and the right, are confusing a historical exception for an ideal. To insist on a return to these conditions is mere nostalgia.

7—“What could have been a generic reality series turns into something much deeper and darker due to him.”

At Home with the Furys is Netflix’s answer to Keeping Up with the Kardashians – or at least it would be if it did not star Tyson Fury. The presence of the former heavyweight champion of the world, Clive Martin argues, lifts it into realms television rarely goes. WL

The real entertainment is provided by Tyson’s increasingly bizarre flights of fancy. He goes to Iceland to confront the strongman Hafthór Björnsson, only to find out his rival is filming an advert in Rome. He flies Paris on a private jet to Cannes to re-propose to her (for the third time). He launches a whistlestop personal appearance tour, with dates as unglamorous as the Isle of Man. After his cousin is stabbed to death in a bar fight, he launches into a powerful, thoughtful speech about knife crime in front of a thousand pissed punters in a Spanish holiday resort.

Just like every other attempt to turn Tyson into a mainstream celebrity, the show eventually buckles under the weight of his charisma – yet it becomes deeper because of that. He’s simply too strange, too powerful, too honest and complicated to contain in a bite-size media persona. It all leaves you with the overwhelming sense that while the producers were aiming for The Real Housewives of Morecambe, they ended up with King Lear.

Will’s Best of the Rest

Politico: Springtime for Europe’s fascists. A sad lack of uniforms here.

The Point: Post-liberalism’s limits.

Bloomberg: Goldman’s war on WFH. It’s going about as well as the Wagner Group’s week.

Ronan Farrow: Elon Musk’s shadow rule.

Magdalene Taylor: Negging, a defence.

Adam Tooze: The end of Chinese infallibility.

Amanda Moore: Undercover with the new alt-right. They seem like a happy, content bunch.

Rachel Connolly: How Ireland took over literature.

Dance like Jane Austen. She prided herself on doing “the worm”.

Who would be a warlord? American Civil War II latest.

Pippa’s Elsewhere on the NS

Katie Stallard reports from the front in Ukraine.

Malcom Kyeyune examines how Sweden lost the plot.

If you don’t know who Masayoshi Son is by now you are missing out. Catch up with Will Dunn.

David Broder reviews Nicolas Sarkozy's new memoir. The former French president, David writes, will be remembered as an enabler of the far right.

“Even the most studied serial killers in history are ascribed motivations that are ultimately nebulous, unprovable, meaningless.” Megan Nolan on Lucy Letby.

How did “BookTok” novelist Colleen Hoover’s blend of fantasy and atrocity come to outsell the Bible? Amelia Tait explains.

The Lionesses may not have ended 57 years of hurt at Stadium Australia, argues Emma John, but they didn’t fail.

Do exams matter? Lorna Finlayson has the answers.

We imprison twice as many people as our northern European neighbours, writes David Gauke (who oversaw the prison system as secretary of state for justice from 2018-19). What could we do to change that?

“Based on a design originally proposed for a quite different site in Ottawa, the plans will involve the reordering of a rare expanse of green space in a cramped area of London.” Rowan Williams questions plans for a Holocaust memorial.

How to get into: Post-war Rome

Each week we ask someone to recommend three books as a way into a subject. This week we turned to Barney Horner, who puts together Morning Call, our weekday political newsletter. Books on Rome are legion, so he has restricted himself to the post-war era, a time of both abundance and crisis in the Eternal City.

Dolce Vita Confidential by Shawn Levy (2016): Levy takes a cultural snapshot of Rome during the Italian economic miracle, from the Fifties to the early Sixties. By lovingly disentangling the fashion, the films and especially the gossip, he reproduces that uniquely Italian blend of the beautiful and the kitsch. The cast of characters includes Federico Fellini, Marcello Mastroianni, the Fontana sisters, Sophia Loren, King Farouk of Egypt, Burton and Taylor.

Stories from the City of God by Pier Paolo Pasolini (2003): Pasolini, the iconoclastic leftist film director, liked to moonlight as a reporter, writing this collection of articles on the plight of the real people of Rome. Away from the Capitoline Hill and the pediments of Ancient and Renaissance Rome, Pasolini gives us the ragazzi thieves and social-housing poor. They, he writes, are the city’s true soul.

The Aldo Moro Murder Case by Richard Drake (1996): In 1978 the militant Marxist-Leninist group Red Brigades kidnapped the former Italian prime minister Aldo Moro, snatching him from the streets of Rome. Two months later he was dead. These were the “Years of Lead”, when waves of political violence from the left and the right arced across Italy. Richard Drake’s finely researched account of Moro’s death and the resulting turmoil remains an insightful, if melodramatic, portrait of Roman and Italian politics in the late 20th century.

And with that…

Thank you for your comments on Keir Starmer last week. The verdict was almost unanimous. I’m not sure I’d call it positive. We shall return to this. On another note, have you heard this song? Have a listen.

Slavoj Žižek saw conspiratorial and neo-Confederate overtones in these lyrics. He joined a chorus on commentators on the internet left who dismissed the song as just another example of populism’s misdirected pain. Anthony was quickly cast as a figure from Trumpland and duly cast aside. The extraordinary impact that Rich Men North of Richmond has had – just try reading the YouTube comments – was rendered irrelevant.

Anthony is an utter unknown. This is the first song he has recorded with a microphone and it is the number one song in America. Something far deeper is happening here. “I see the right trying to characterise me as one of their own, and I see the left trying to discredit me… [but] this isn’t a Republican and Democrat thing. This isn’t even a United States thing,” Anthony said in a video yesterday. You will learn more watching these videos – of Anthony sitting in his truck, talking to camera, trying to stay on the ground – than you will reading any rapidly filed piece on him.

Thank you for reading. Don’t miss out – subscribe to the New Statesman and stay up to date with everything you need: from news and analysis to comment and criticism.

Whether you’re looking for a sharp blog or a finely written feature, the New Statesman has you covered. Have a good week, and catch you next Saturday.

Thanks to Chris Bourn and Pippa Bailey.