The Saturday Read: Towards the void

Inside: Goya, Maçães, Shipman, Columbia, Khamenei, Friedrich, and Rushdie III.

Good morning. Welcome to the Saturday Read, the New Statesman’s weekly guide to politics, culture, books, and ideas. This is Harry, along with Jason, Pippa and George.

Today Jason introduces us to two pieces from this week’s issue before Pippa, newly returned to London, and George each select three.

If you are short of detail on Mike Johnson, the Republican Speaker of the House who finally allowed $60 billion in Ukraine aid to pass last weekend, I wrote a note on his other great cause: fuelling Donald Trump’s bid to invalidate the 2020 election. He was only able to play the hero this week because of the far from heroic role he played then.

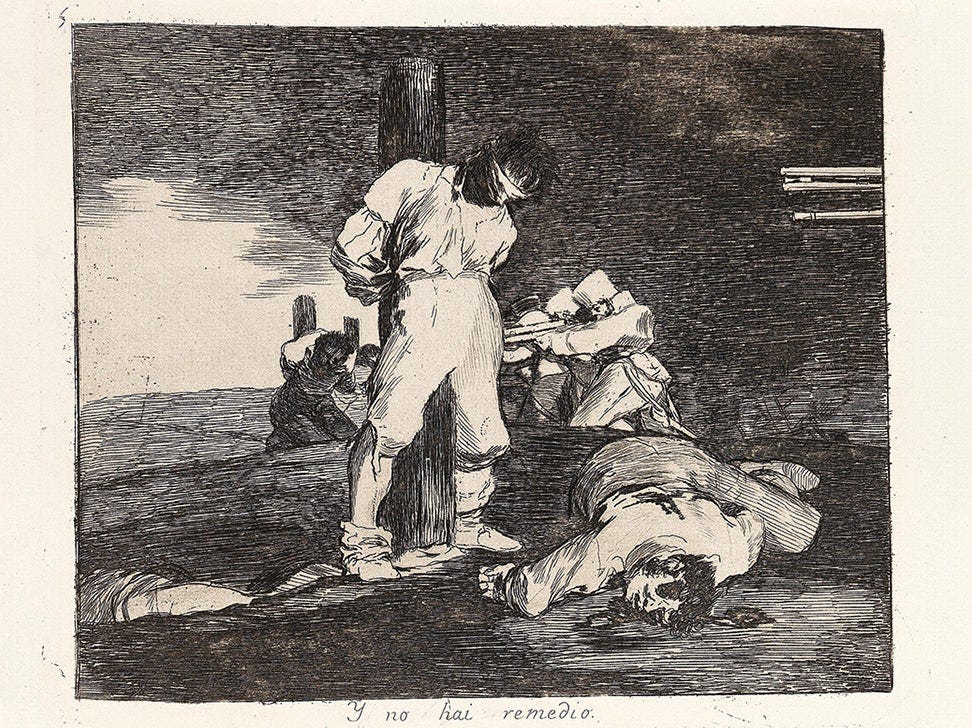

During Holy Week I spent three days in Madrid, my first visit to that remarkable city. I’d been to Spain many times before but never to the capital, and so on consecutive days, in unseasonably cold weather, we visited the Reina Sofía Museum (home to Picasso’s Guernica) and the Prado Museum, with its astonishing collection of masterpieces: The Garden of Earthly Delights, Las Meninas, The Descent from the Cross, The Third of May 1808…

We’d planned also to visit the San Fernando Royal Academy of Fine Arts, where, for the first time, all of Francisco Goya’s print series (from the 1810s), The Disasters of War, is on display. But other attractions tempted us away. The highlight of our final day turned out to be a visit to the venerable Santiago Bernabéu for the Spain vs Brazil friendly. It rained but it was a good game: 3-3.

My colleague Andrew Marr was in Madrid a few weeks after me – I hear the weather was better – and very sensibly he visited the San Fernando Royal Academy. He writes about the experience in a compelling essay in this week’s magazine. There, looking at Goya’s sketches, until his back throbbed and feet hurt, he saw something he’d never seen before in Goya’s work: a representation of our own contemporary world.

“We have lived over these past few decades,” Andrew writes, “in a most unusual bubble of local peace, in which we are sold the belief that liberal democracy, working with ever more dextrous and intelligent technology, will deliver us from evil. We had almost come to believe that the modern monsters – racism, violently superstitious religion and totalitarianism – were quitting the planet. This is the moment for Goya.”

Our cover story is also on the theme of war – or, more precisely, what its author, Bruno Maçães, calls the globalisation of conflict. Are these times more dangerous than, say, the long 1970s, at the height of the Cold War, during the energy crisis, with the old Keynesian welfare-capitalist consensus unravelling in Britain and elsewhere, opening the way for the market-driven transformations of the new right?

Or does it just feel like that, as the war in Ukraine grinds on following Putin’s full-scale invasion and the Middle East seethes and burns? For Maçães, we are living among the ruins of the postwar liberal order, which is why we are calling this “the age of danger”. But just how dangerous is the new world (dis)order?

1—“This is proper work, the real stuff of understanding.”

The third book in Tim Shipman’s monumental Brexit quadrilogy is out and has brought the present page count to 1,950. Andrew reviews. “What the Roman empire was for Gibbon, Brexit is for the man universally known as Shippers.” (We’ll have more from “Shippers” tomorrow for subscribers to Morning Call, our weekday political newsletter. Sign up for that here.) GM

But if you are interested in politics, you have to be interested in this. And I can’t resist ending this review with the book’s conclusion, which seems to me unarguable: “May would hate this valediction but in the final analysis her premiership so exhausted the possibilities of Remain pessimism, of cautious, details-oriented technocratic grinding, of stilted, charisma-free communication, that she not only made possible the premiership of Boris Johnson – a Brexiteer optimist and gambler, a big-picture improviser and an arresting speaker – she made it inevitable.

“More than that, for the overwhelming majority of her own party she made Johnson necessary if the referendum result was to be respected… The advocate of caution and duty bequeathed the country a successor prepared to risk chaos to get what he wanted.”

2—“These kids will do just fine in the HR department.”

Sohrab headed over to what you might have thought would be a volatile political flashpoint: Columbia University’s “Gaza encampment” on New York’s Upper West Side. He walked away unimpressed. GM

A radical threat, a harbinger of civil conflict, or a revolutionary movement, the campus intifada is not. On the contrary, it’s by venting built-up pressures of this kind that democratic states like the US stabilise the social order. And anyway, the bright kids involved are too wedded to the logics of the corporate, safety-ist society against which they rebel to pose any serious challenge to it. It’s hard to imagine streetfighters such as Tom Hayden or Daniel Cohn-Bendit in their heyday tsk-tsking: “We want to ensure people feel comfortable in this space.”

3—“The ‘strategic patience’ Iran long prided itself on ran out on 1 April.”

The veteran war reporter and BBC chief international correspondent Lyse Doucet writes in this week’s Diary about the off-ramp Israel has gifted Iran. Ayatollah Ali Khamenei’s new doctrine is to “hit back, hard, immediately”, and no longer through its proxies across the Middle East. PB

I keep remembering the days of June 1989, my first trip to Iran. The gates were flung open to allow journalists to enter, without a visa, by midday on 6 June, the day Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini was being laid to rest. We made it, with minutes to spare. The human tide surging through the streets of Tehran was so frenzied the ayatollah’s body slipped from its coffin and was briefly carried away by the crowd. Khamenei was unexpectedly selected as his successor, seen by some then as a mullah who wanted to repair ties with the West and rebuild Iran after its long, devastating war with Iraq. Decades on, his speeches are now soaked in venom against the West, especially the US, and Israel, “the usurper Zionist regime”.

4—“This was different – an important and shattering thing.”

Megan Nolan really didn’t want to watch Baby Reindeer: “Netflix, stalker, crazy woman, blah blah blah.” But she found that the seven-part hit series understands abuse like no other, including how alien it seems to the external observer – and, with hindsight, to the abused. PB

Many other people exist without being abused, after all, so if you continuously attract menace, mustn’t it be because of some secret badness in you? That badness you have always felt throbbing inside, no matter how many people love you? That badness you have hoped to conceal but must be, if multiple people have singled you out for attack, visible to the outside world? This, despite being objectively insane, feels so obvious a conclusion to the abused party as to be beneath mention. But what I could see so clearly watching Baby Reindeer, as I myopically could not while watching the events of my own life, is the simultaneous extreme sophistication and extreme idiocy of the human mind as it attempts to cope with something unbearable.

5—“The world has abandoned realism.”

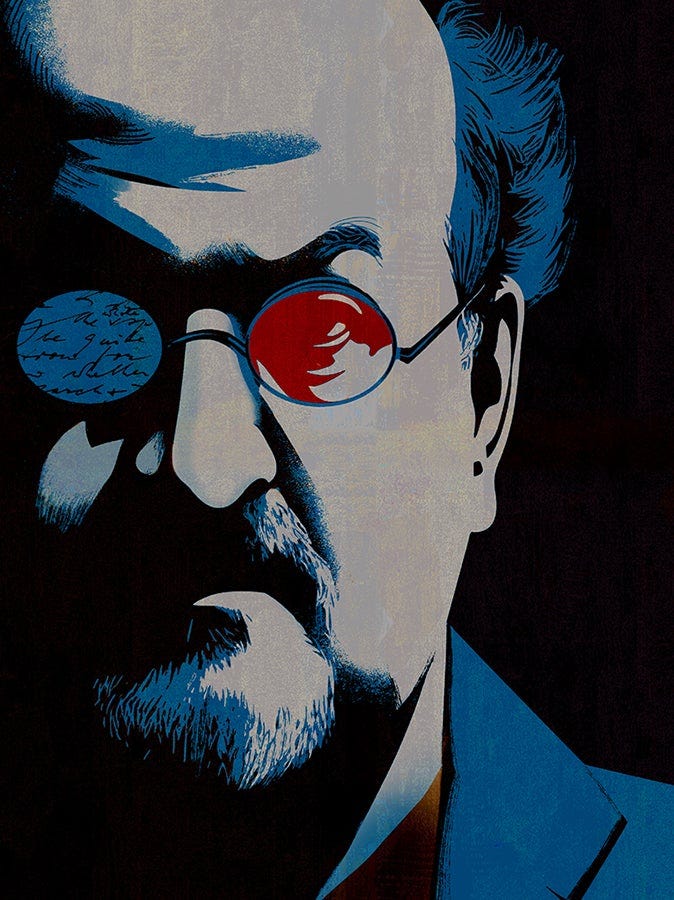

In the 36 years since the publication of The Satanic Verses, Salman Rushdie has paid for his belief in free speech, not least in the attack that cost him an eye. Last Sunday, at London’s Southbank Centre, Rushdie spoke with the New Statesman contributing writer Erica Wagner about how writing his memoir of that attack, Knife, gave him power, and how optimism saved his life. PB

“This is somebody who was 24 years old, and he must have known that he was going to be wrecking his life as well as mine. He’s somebody with no previous criminal record, and not on any kind of terrorism watchlist. Just a kid in Fairview, New Jersey. To go from that to murder is a very big jump. And his motivation – what we know about it – seems trivial: that he had read no more than two pages of something I’d written, he doesn’t say what, and that he’d seen a couple of YouTube videos.

“If I were to write a story in which somebody decided to murder a stranger on the basis of such flimsy pretexts, my publisher would say, ‘Not good enough, not convincing,’ and yet that’s what happened. So I thought: ‘There’s an empty space in the middle, and I want to try and imagine myself into him so I can try and fill up that space and try and understand why a kid from New Jersey would be willing to murder a total stranger.’”

6—“It is a love painting.”

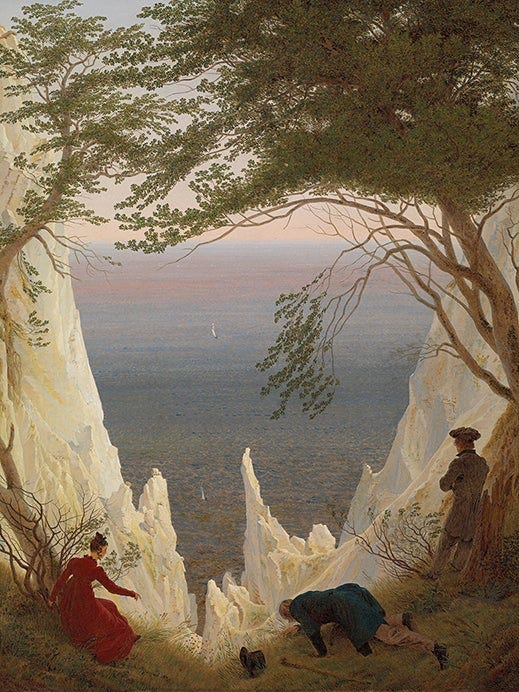

This year marks the 250th anniversary of Caspar David Friedrich’s birth. You will know his Nietzschean Wanderer Above the Sea of Fog, but now it is time for softer lights. Michael Prodger, our art critic, introduces us to a great and sensitive personality and leads us up to one of Friedrich’s most intimate works. GM

Christian’s very presence was a reminder of the unpredictability and brutal transience of life. In 1787, Caspar was ice skating with his 13-year-old brother Christoffer when the ice broke and Caspar fell through. Christoffer dragged him free but in doing so went under himself, and could not be saved. Back home, traumatised at having caused his brother’s death, Caspar locked himself in his room and tried to kill himself; he was only saved when his family broke down the door. Christian was therefore doubly dear to him and if, in Chalk Cliffs on Rügen, he is drawn irresistibly towards the void, it is because he had already touched it.

It has been three years since Uber and GMB signed their recognition agreement. Together they have delivered the first pension in the gig economy. But what is the future of work in 21st-century Britain? And how do we combine autonomy and flexibility with security and representation? Join our panel of experts for a New Statesman podcast produced in collaboration with Uber, to discuss all of this and more.

George’s Best of the Rest

BBC: Humza Yousaf’s leadership imperilled after power-sharing deal collapses.

Telegraph: Five migrants die crossing the Channel.

FT: Labour pledges to fully renationalise rail network. Ready for my Keir Card.

Freya Johnston: Samuel Johnson’s criticism.

Lara Spirit: The asylum crisis will migrate to Starmer. Essential reading.

Rob Lockwood: Electric, intoxicating masculinity.

Maggie Mertens: Marathons, the new quarter-life crisis.

Clinton Rogers: Idleness and Shakespearean sonnets.

Portugal celebrates 50 years of post-revolution democracy. Saúde!

Anniversary of Athenian surrender to Sparta. Still not over this.

If today’s pieces intrigued, you can subscribe to the New Statesman below. Stay up to date with everything from news and analysis to comment, criticism and essays.

Whether you’re looking for a sharp blog or a finely written feature, the New Statesman has you covered. Have a good week, and catch you next Saturday.