The Saturday Read: Turns 1

Inside: QE, Ukraine, literature's divide, Disney, Vice, the woke revolt and a trader's tale.

Good morning. Welcome to the Saturday Read, the New Statesman’s weekly guide to politics, culture, books, and ideas. This is Harry, along with Will, Pippa, and George.

Thursday was a leap day. Think back to the last: 29 February 2020. The pandemic is about to hit. I was on a coach to Paris, warily eyeing the other passengers, taking a last minute trip before our island’s drawbridges rose. How much has changed since? Workplaces have been transformed, not all for the better. Ukraine was invaded, Israel attacked, Gaza destroyed. The Tory party has imploded. David Cameron has risen from the political dead. The market cap of Nvidia, the world’s leading microchip maker, has increased by $1.9 trillion, as much as the GDP of Australia. Stock markets collapsed during Covid only to recover with ease. Trump was buried by a thousand columnists. Now he’s odds-on to be president. Our forecasts never cease to err.

And the woke revolt, whatever it is exactly, has continued to remake countless organisations while facing far greater scrutiny in public. This week the Atlantic once again pored over the entrails of the Tom Cotton op-ed that ran in the New York Times in 2020. The junior editor responsible for the piece told his side of the story for the first time, offering a refreshingly specific account of how others inside the organisation pursued him. Was this a witch hunt?

In other media news, Mehdi Hasan, formerly of this parish, launched a new media company (“Zeteo”) through Substack. The media houses of the future are being built on here. Zeteo is the counterpoint to Bari Weiss’ The Free Press. When I spoke to Mehdi last year he told me he thought the American centre left had become “technocratic, managerial and bureaucratic. They’ve shied away from emotive hot button issues. What the right has done so cleverly is to use emotion to energise their side of the political spectrum.” He now plans to do that for the “liberal” left. Meanwhile in Britain, the BBC upheld a complaint against Justin Webb, the Today presenter, for referring to trans women as male, provoking disbelief.

Finally, the Saturday Read turns one this weekend. Thank you for reading. We have a set of fascinating pieces for you today, and Will has signed us off.

1—“QE has quietly become the defining idea of our time.”

Have you ever looked out across our modern world and wondered why Donald Trump, Deliveroo, Harry and Meghan, Elon Musk, and Instagram all provoke the same vague feeling of seasickness? In this week’s cover epic, Will Dunn has the answer. It’s all the consequence of Richard Werner – a then 28-year-old banker living in Hong Kong – having an idea in 1995. That idea was quantitative easing: printing money and buying up government bonds with it. My highlights ran to 1,200 words. GM

By the end of the 1980s, Japan’s money was everywhere. Between 1970 and 1991, Japanese foreign investment had grown by 100 times. As the largest net investor in the global economy, Japan bought US computer companies and movie studios, Van Gogh’s Sunflowers, and the skyscrapers of New York City and Los Angeles. Pervasive in the culture of the time – in Blade Runner, Michael Crichton’s Rising Sun and even John McTiernan’s Die Hard – was the idea that the future belonged to Japan. Werner’s research focused on a simple question: where was all that money coming from?

The bubble touched everything. When a young couple applied for a mortgage to buy their first home in Japan in the late 1980s, they were typically offered twice the value of the property. A golf-club membership could cost $3m. An airport-sized piece of central Tokyo had a greater land value than the whole of Canada. It was common for people to talk about the country’s “excess money” over dinner; in one Osaka restaurant the market predictions of the owner, a former nun called Nui Onoue, made her for a time a celebrated stock-picker, so much so that financiers loaned her hundreds of billions of yen to invest.

2—“The war is lost but our governments refuse to admit it.”

Two years on from Vladimir Putin’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine, the fight continues, with the Russian economy untouched by sanctions and American support for Kyiv faltering. We asked Andrey Kurkov, Margaret MacMillan, Ivan Krastev and others to reflect on Ukraine’s next move, and how the conflict could end. PB

We appear to be headed towards a partition of Ukraine, with the occupied east and south (including Crimea) rejoining Russia, and the north-west linking back up to Poland, the old Habsburg lands and central Europe more broadly. That still leaves a lot of middle ground to fight over. Whether the frontier will follow the Dnieper river or the Oskil river is being settled on the battlefield. Western Ukraine’s longer-term institutional arrangements (EU? Nato?) are, of course, unclear. Both semi-states will surrender their sovereignty, although the western one will be permitted, like its EU neighbours, to pretend otherwise.

3—“Writers do not warm to being threatened and silenced.”

“Managerial censoriousness” is how Lisa Appignanesi describes the divisive atmosphere at the embattled Royal Society for Literature. Ellen Peirson-Hagger reports on the “puzzling” disputes that appear to be tearing the society apart. WL

Fergusson recalled “an atmosphere of intimidation and fear” at the last annual general meeting in November 2023, when a fellow attempted to say that the RSL had not given sufficient support to Rushdie. “I gather she was simply not allowed to speak freely.” The RSL has since said that it “categorically condemned this horrific attack”. The two tweets from the RSL’s Twitter account in August 2022 offer “thoughts” and “strength” to Rushdie and his family but do not condemn the attack.

4—“Who told them to seek escapism instead of an escape?”

Proud “Disney adults” who post videos of themselves overcome with emotion at the company’s theme parks are the intentional creation of the Walt Disney Company. For decades, the conglomerate has sought to provide adults with a childish, untroubled escape – and to profit from it. Amelia Tait goes deep inside the Disney adult industrial complex in this weird, wonderful piece, which was everywhere this week. PB

Over the past 100 years, the Walt Disney Company has entwined itself with our families, memories and personal histories. In many ways, Disney is a religion that one is born into, the same way a 15th-century English baby was predestined to be baptised Catholic. Choice doesn’t necessarily come into it – we see Mickey Mouse around us like our ancestors saw the cross; a symbol that both 18-month-olds and 80-year-olds recognise. But if we accept that Disney adults were created, rather than spontaneously generated, then why are we scrutinising the congregation instead of the church?

5—“There was a fury in his discovery.”

If there is one story that captures the Age of Austerity, Gary Stevenson’s new book may be it. He made millions betting that it would choke off economic recovery, as it did. I reviewed it for us. Come for the arresting tale, stay for the vividly drawn characters. HL

You don’t get given a job as an intern – you have to carve one out. The Trading Game is at its best when Stevenson brings alive the unease of trying to survive in the purgatorial space between being an employee and an outsider. That tension is particularly acute on the trading floor, where Stevenson is thrust – at the end of a row, with a filing cabinet for a desk – among the characters (all men) who populate his book. There is Caleb, the gleaming, precocious 28-year-old in charge of the team, whose confidence rose off him “like smoke from a candle”; Rupert, whose imperious manner and muscular-yet-fat physique fits his boarding-school class; JB, the Australian former rugby player whom younger, smarter, and hungrier men such as Stevenson will eventually eclipse; and Bill, the small, withdrawn, white-haired Liverpudlian who just happens to be the best trader in the building.

6—“We were building ice sculptures in Death Valley.”

Clive Martin was one of the finest writers Vice published. With the company ceasing publication on Vice.com – effectively announcing its own death – I thought it might be a good time to hear from him. He has written a wonderfully bittersweet piece. WL

It was exactly how a “creative” company should be. If you had an idea at Vice, you could get it published, get it made, and get it out there, with few questions asked. People that had never written anything longer than a Ucas statement were given huge viral hits just because they had a story, an idea, something to show the world. Interns sometimes found themselves working – and sometimes leading on – documentaries that were primed to reach 30 million views. Writers were dispatched around the country and sometimes internationally, told to come back with something, and if it didn’t work, no worries.

7—“It is unsurprising that many academics keep their more ‘toxic’ views to themselves.”

Edward Skidelsky acknowledges that the crisis of free speech in British universities is a “godsend” to the right, while suggesting some unusual reasons for why it’s so difficult for academics to say or write what they actually think. This week he launched the Committee for Academic Freedom in London. WL

For many years, left-wing opinion-makers have told us that there is no crisis of free speech in British universities, that the whole idea is a fiction put about by right-wing bigots upset that they can no longer sound off with impunity, or by politicians and journalists intent on stirring up a culture war. To quote Nesrine Malik, writing in the Guardian in 2019, “the purpose of the free-speech-crisis myth is…to blackmail good people into ceding space to bad ideas”. Anyone who works in a university knows that this is balderdash. The crisis in academia is of course a godsend to the right, but that doesn’t mean that it isn’t also real and serious. Indeed, it is much more serious than most people realise.

8—“Musk aims to tear down Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s New Deal.”

While America’s media class is distracted on his social media platform X, Elon Musk has been leading a courtroom putsch to return the US labour market to the 19th century, when bosses were all-powerful and workers are left without recourse. In his latest column, Sohrab Ahmari argues that populist Republicans must now decide whether to stick or twist on their declared love “for the oppressed working class”. PB

The challenge is notable not least for laying bare the capitalist class’s capacity to join forces across apparent cultural divides. Musk is something of a political outlier among his fellow executives, who are increasingly withholding their advertising dollars from his social-media platform over its profusion of cranky content. Trader Joe’s boasts a lefty California vibe and touts its commitment to diversity and inclusion. Amazon has cultivated a progressive image, leading corporate America’s Black Lives Matter advocacy in the wake of George Floyd’s killing in 2020. Yet when it comes to shared class interests, cultural disagreements melt away. Musk, Bezos and the family owners of Trader Joe’s act as one.

9—“Civilisation thrives on cross-pollination.”

Josephine Quinn’s new book, a “4,000-year history”, makes two major arguments. First, Earth’s culture is indivisible: concepts like “the West” are misleading and dangerous. Second, history exerts no real influence on us. The powerful and living choose which parts of the past they want to remember. Lucy Hughes-Hallett reviews How the World Made the West and finds it “an immense achievement”. GM

One of the big ideas behind her book is that civilisation/culture (the terms are not exactly interchangeable) has evolved through a process of exchange and communication linking human communities over millennia and across vast tracts of land and sea. Civilisation is at once an amorphous but unified whole, and a conglomeration of thousands of separate cultures, in each of which shared elements are differently combined. Quinn argues that the habit of bundling those entities according to geographical principles – as Europe, Asia and Africa; or as West, East and South – is so simplistic as to lead to all sorts of false conclusions, some ideologically toxic (West is best), others just plain wrong.

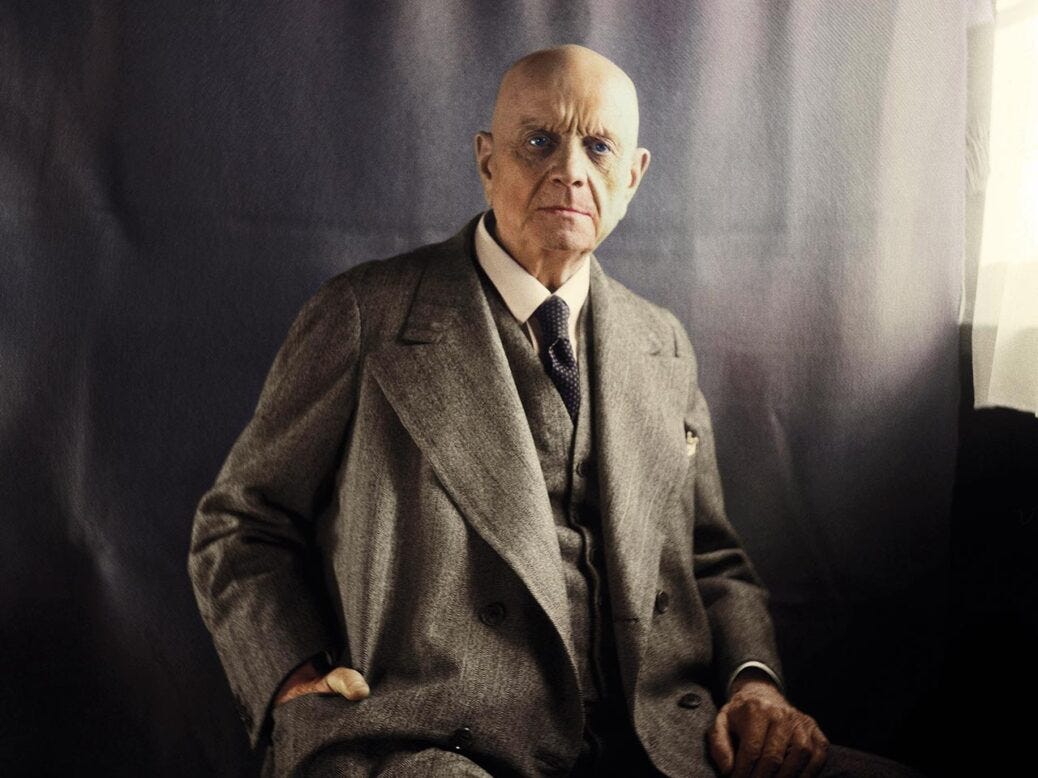

10—“He struggled, it has been argued, because he had nowhere left to go.”

The Finnish composer Jean Sibelius spent his final three decades as a recluse. His works drew large crowds but he could produce nothing new. He was seen, at once, as both glorious and pathetic. In those years he attempted an eighth symphony, but threw the score into his fire. Phil Hebblethwaite examines his seventh for clues to the 33 years of desolation it announced. GM

In 1907, Sibelius met the other great symphonist of his age, Gustav Mahler. Their conversation, reported by Sibelius, reveals a stark difference in thinking. “I said that I admired [the symphony’s] severity of style and the profound logic that created an inner connection between all the motifs… Mahler’s opinion was just the reverse. ‘No, a symphony must be like the world. It must embrace everything.’” Mahler had just completed his epic, 90-minute Symphony No 8 for three sopranos, two altos, tenor, baritone, bass, two mixed choruses, boys’ choir, organ and huge orchestra. Sibelius, on the other hand, was soon to work on his lean and menacing, 35-minute Symphony No 4 – a “psychological symphony”, as he called it. It moved away from the landscapes and mythical legends that inspired so many of his previous works, tackling his fears and anxieties.

Will’s Best of the Rest

Bloomberg: France and Germany’s broken relationship is harming Ukraine.

Axios: Christian Nationalism isn’t just a white-people thing.

Carlos Lozada: I read 900 pages of Trump’s second-term plans.

Philip Pullman: “Did I like Harry Potter? Not enough to read a second book”. I never read the first book of His Dark Materials (no offence Phil).

Fintan O’Toole: Is Trump funny? Yes.

Lotte Brundle: Searching for Paul Mescal.

Patrick Maguire: Ken Livingstone tactics could be Sadiq Khan’s undoing.

The rise of the do-nothing holiday. Goes hand in hand with the rise of the do-nothing job.

More South Korea baby bust. It’s all K-pop’s fault.

In addition

This week I caught up with this fascinating conversation between Lawrence Freedman, whom we interviewed in September, and Margaret MacMillan, a fellow contributor to the NS. MacMillan: “I find it very interesting that two of the best biographers of the current day, Ian Kershaw, with his biography of Hitler, and Stephen Kotkin with his biography of Stalin, both started out as social historians and both came to the conclusion they couldn’t understand the systems they were studying without understanding the men at the apex.” HL

Elsewhere on the NS

“Pandemics tend to strike when both the human body and the body politic have forgotten the last one.” Laura Spinney examines a new book on how Covid hit the skyline city, New York.

The UN’s Reem Alsalem makes the inarguable case that sex and gender must not be conflated if we are to end violence against women.

Andrew Marr is in no mood for Tory deceit and lays down some hard truths about democracy.

Anoosh Chakelian meets Dan Neidle, the retired tax lawyer who brought down Nadhim Zahawi and turned his sights on Michelle Mone.

History is not a moral court, Richard J Evans argues in our weekend essay.

George Eaton tracks the new split on Labour’s hard left.

Europe’s climate consensus is crumbling and Ursula von der Leyen is in danger of wrecking her own green programme, argues Wolfgang Münchau.

Elif Shafak writes on why she’ll always hold a candle for James Baldwin. Literally.

Peter Williams very amusingly reviews a book about the forgotten members of rock and pop bands, and the “winningly awkward presence” of its author.

Our unparalleled TV critic Rachel Cooke has reviewed The Jury: Murder Trial, a new and disquieting Channel 4 series.

And with that…

Few groups in Britain are as reliant on the whims of regulators, markets, negotiators, shifting ideological fashions and politicians as Welsh farmers; few groups are as powerless. Their protests in recent weeks, which mirror similar rebellions in continental Europe and were unerringly foreseen in Michel Houellebecq’s choppy 2019 novel Sérotonine, have attracted little attention in the rest of Britain.

In contrast with other recent social justice movements, the Welsh farmers have not hijacked the headlines. They have not been invited to guest edit magazines in London. Their grievances have not led to so-called reckonings on the boards of publishing houses, charities, the civil service, arts institutions or the BBC. Perhaps the demonstrations of the kind we have seen in Wales – with tractors blocking roads and the storming of political meetings – would be headline news were they being organised by a more appealing demographic group than the poor old Welsh.

Not that the farmers seem bothered by Britain’s inattention. “Wherever [Welsh first minister Mark] Drakeford and his colleagues go, they will find tractors on the roads and people on the streets,” a Pembrokeshire dairy producer told the Daily Mail. “I’ve been farming my whole life, and have never known anger like it.”

If today’s pieces intrigued, you can subscribe to the New Statesman below. Stay up to date with everything from news and analysis to comment, criticism and essays.

Whether you’re looking for a sharp blog or a finely written feature, the New Statesman has you covered. Have a good week, and catch you next Saturday.