Good morning, and welcome to the latest Saturday Read, the New Statesman’s new weekly guide to the best writing on ideas, politics, books and culture. This is Harry Lambert. If you are receiving this email you are either a regular Saturday Read reader or an NS subscriber we are now sending this to as part of our subscription offer. This week we have eight picks from across the New Statesman, a handful of other NS articles you might like, and, as ever, 15 links to intriguing pieces in other outlets.

Why doesn’t anyone, asks Will in today’s sign-off, read novels any more? I was not one of the 40 friends he asked this question to this week: he knows I am lost to the non-fiction that piles high each week in the New Statesman books cupboard. Eight books caught my eye on Monday, but why are they almost all 300 pages or more? What is this publishing world rule? I’d pay as much for a book that told me all I needed to know in half the time. I’ve read 100-page novels that changed my life (here’s one).

How about you? Do you still read novels, or something else? Leave a comment and let us know, or get in touch by replying directly to this email. We’d also welcome your thoughts on any of the pieces below. If they interest you, you could try a trial subscription to the NS. You can read three free articles after registering on the New Statesman website. A digital subscription is just 95p a week. Let’s get to it.

1—“The most common question is: is this 2008 again? The short answer is no.”

So what is it? Our business editor, Will Dunn, takes us through one of the shakiest weeks in recent financial history. After three mid-size US banks collapsed in quick succession, and Credit Suisse was forced to sell itself to its longtime rival UBS, Dunn explains where we might be headed next – you can catch Will’s cover story on newsstands now.

But while there are echoes of the 1980s, this is also something entirely new: a banking crisis in a world with emerging systemic risks and with a war raging in Europe. The 2008 crash occurred after a long period of stability, an apparent Great Moderation, in which many policymakers assumed risk had been tamed; the current crisis is happening in a world economy struggling to recover from a pandemic and in which Vladimir Putin’s Russia has invaded Ukraine.

In 2008, the technical and social networks on which information travels were very different. WhatsApp did not exist, Twitter and even Facebook were relatively niche platforms, and the iPhone was an expensive luxury. These technologies have radically changed the speed of what the economist Robert Shiller – who won a Nobel prize for his work predicting the dotcom crash – calls “narrative economics”. Shiller’s work shows that the conditions for events such as the 1929 Wall Street Crash were laid not only by the blind arithmetic of the market but by millions of conversations, on trains and at dinner tables, about the investment decisions of everyone in the economy.

2—What really happened at Kettlethorpe?

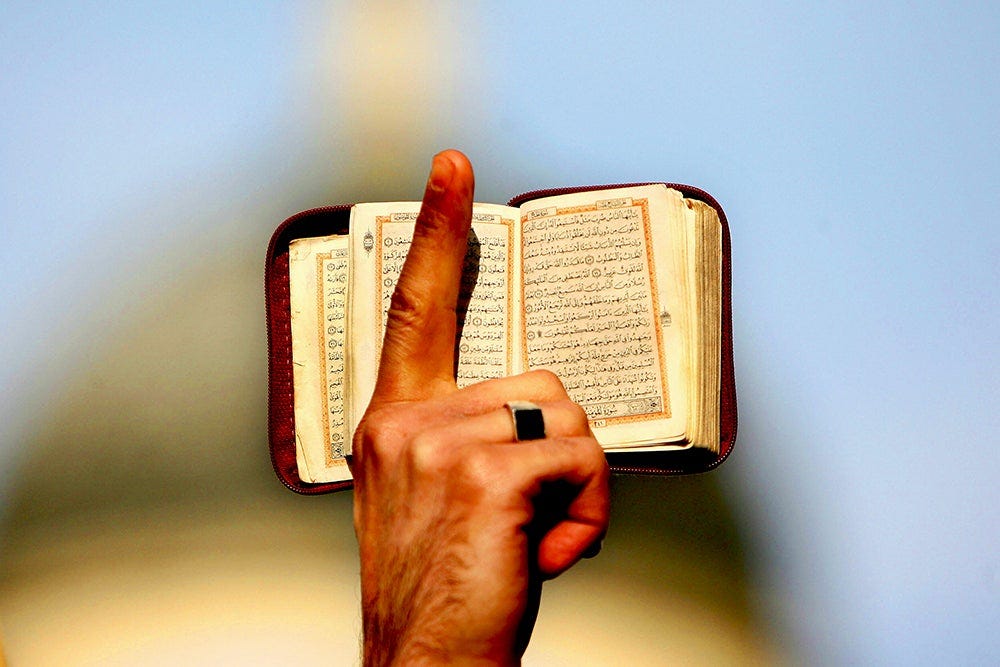

A month ago, a news story caught fire online, and was soon seized upon by Suella Braverman, the Home Secretary. A copy of the Koran had been scuffed by a group of schoolboys at Kettlethorpe High School in Wakefield. Two days later, an open meeting was held at a local mosque. Video clips of that meeting soon went viral.

The footage appeared to show a woman – the mother of one of the boys – being forced, out of terror, to plead for her son’s safety. I went to Wakefield last week to work out what happened. How did mother come to be in that room? My understanding of the event was upended by what I discovered.

“What is a trial?” said [Akef] Akbar, who is also a solicitor, when we met on 16 March. “A trial is where you judge somebody. Who was judging this lady? She was treated with the highest degree of respect. I walked out with her. Everybody was coming up to her, saying how brave she was.”

But why did the mother need to be brave? Whose anger was she confronting? The fury was not felt in the room. If you listen to the full video, the crowd is calm. The point of the meeting, the imam told me, was to address the “frustration being felt by a number of Muslims” elsewhere, and assure them that the Koran had not been burnt or desecrated.

In the clips shared online, the most emphatic message delivered by the imam was missed. “In any element of the history of Islam,” he says at one point, “you will never see any part where the prophet ordered violence, or asked a companion to go and harm someone. So anyone who thinks that it is appropriate to put threats out on social media, or to cause anyone fear, alarm or distress – that person is not truly following the teachings of Islam. It is as simple as that.”

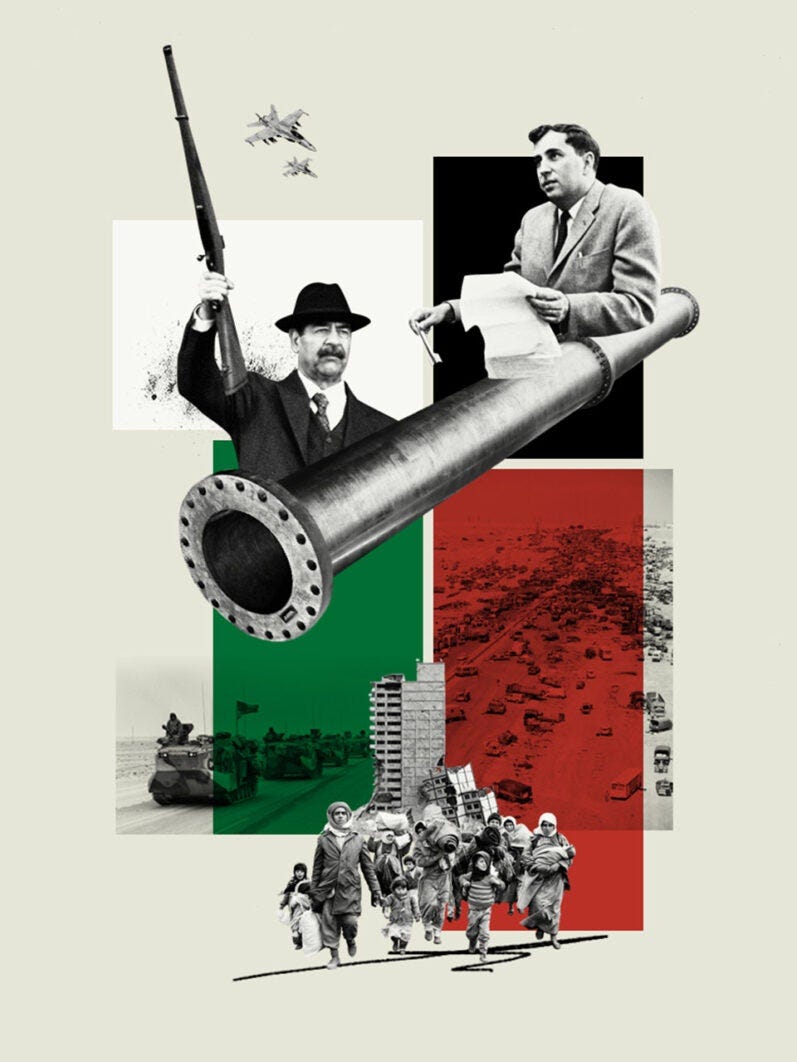

3—”It was a catastrophe decades in the making.”

Noah Kulwin goes deep into Iraq’s past to produce this remarkable slow-burning tale of how Britain and the US armed Saddam Hussein. British involvement in Iraq long pre-dated Blair.

The UK was one node of a proliferating “Iraqi procurement network” – a vast array of international arms companies, military suppliers, banks, front companies and spy agencies. Rougher customers participating in these schemes included the Saudi arms trafficker Adnan Khashoggi and the Chilean dealer Carlos Cardoen; blue-chip companies with links to Iraq included America’s DuPont and Japan’s Hamamatsu.

Among the Europeans, West Germany sold chemical munitions, France contributed nuclear know-how and engineering, but perhaps the murkiest and most tawdry connection to Hussein’s regime were those British companies who worked with a man named Gerald Bull and a project called the “supergun”.

4—"To avoid a brawl, I offered to follow them out to the street, alone."

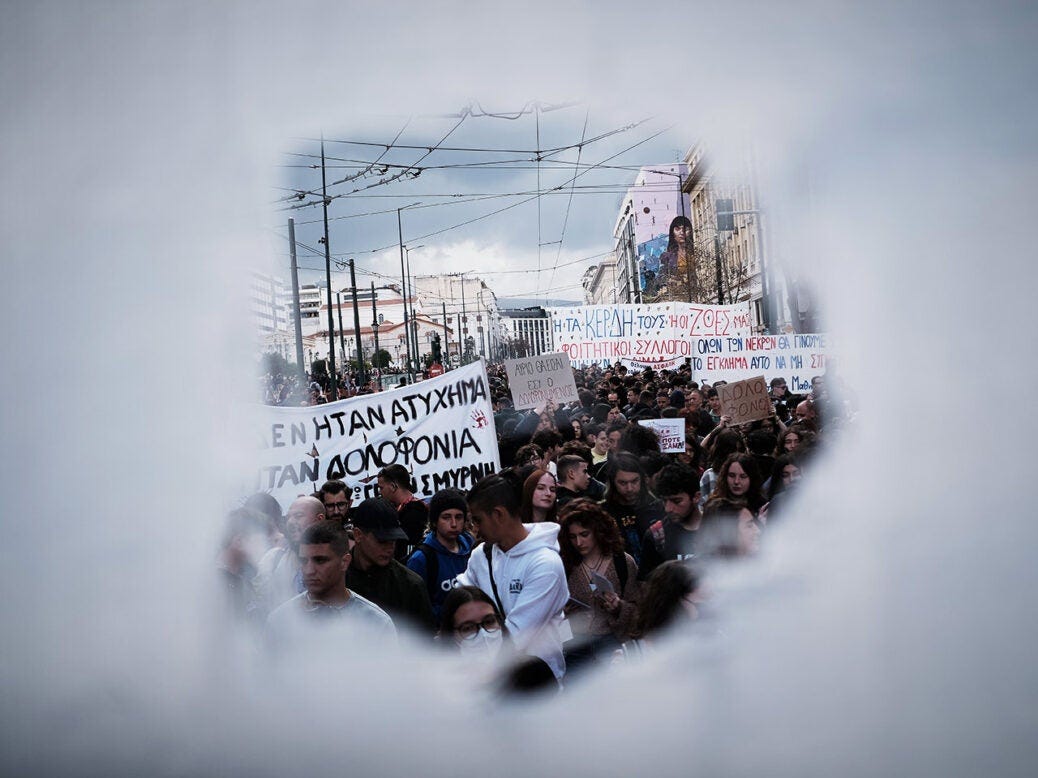

Greece’s most famous politician – who we were the first to interview when he resigned as Greek finance minister in 2015 – has written for the NS this week about being beaten up by fascist thugs in Exarcheia, the anarchist neighbourhood of Athens.

One of the troika’s preconditions during the debt negotiations [in 2015] was that I sign a memorandum of understanding (MoU) under which our trains would be sold off for a pittance to an impecunious Italian state-owned company, our main port to a Chinese state-owned company, and our airports to a German state-owned company – a wholesale takeover of key infrastructure by three foreign states.

As we were exiting the restaurant, pushed and smacked by their ringleader, one of them denounced me as a signatory of the hated MoU and the privatiser of the railways. [Varoufakis had in fact fought privatisation.] Once outside, the ringleader, a man in his late twenties with the look and demeanour of a nightclub bouncer, punched me in the face in the style of a professional, causing me to lose my balance and fall on the pavement – at which point he proceeded to kick me in the face.

5—“We are licensed jesters, OK?”

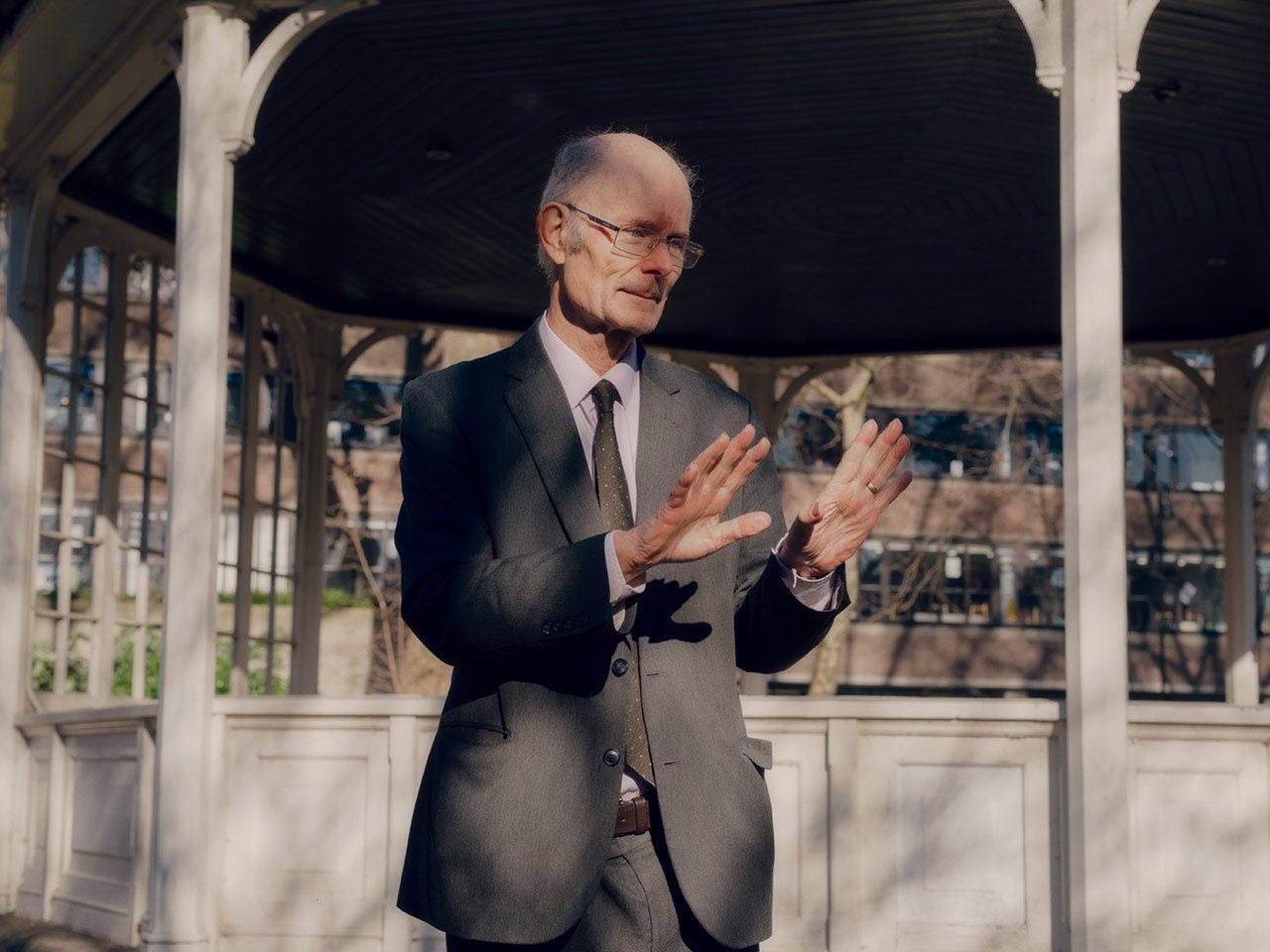

Britain’s most famous psephologist, John Curtice – who runs the exit poll on election night – has spoken to Anoosh about the state of the polls. His verdict: the Tories are “stuffed”.

“If you’re 20 points behind in the polls, and we saw anti-Conservative tactical voting kicking in last year – if all that remains, then surely the Conservatives are on a hiding to nothing,” he said. “The economic position looks terrible. We’re back to the 1970s, concertinaed into 12 months. We have industrial unrest, high inflation, fiscal crisis, a dramatic fall in living standards – oh, and by the way, even though we’ve got record taxation and public spending, the service levels are crap.”

A hung parliament is “still in the game”, he added, but as the Tories “don’t have any friends inside the House of Commons” they have little chance of forming a minority government. “Unless they can get about 320 seats, they’re stuffed.”

6—“The visit to Moscow involves a significant gamble for Xi.”

The long, troubled history of Sino-Russian relations has been fraught with mutual suspicion and periodic violent clashes, writes Katie Stallard. Yet this week, which saw Vladmir Putin and Xi Jinping meet for high-level talks in Moscow, arguably represents the dawn of a new era for both countries.

Xi values Putin, as the leader of a long-established global power with a permanent seat at the UN Security Council and significant trading relationship with the Global South, as a partner in their shared competition with Washington. Beijing fears that if Russia is comprehensively defeated in Ukraine, then the US and its Western allies will be free to focus their full attention on China. Worse still, the collapse of Putin’s regime could bring a new pro-Western (or at least less vehemently anti-Western) government to power on the other side of their 4,000km border, which would represent a strategic nightmare for the Chinese leadership.

7—“People who study cults sometimes end up joining them.”

A blistering review from Oliver Eagleton of Matthew Goodwin’s new book, Values, Voice and Virtue: The New British Politics. According to Eagleton, Goodwin has become part of the right-populist movement he once sought to explain.

When setting out these positions, Goodwin often sounds like a duller Piers Morgan. Yet, unlike Morgan, he tends to obscure his most unpalatable opinions behind a dense thicket of polling data – distancing himself from their pernicious implications by informing us that this is simply what the average Red Wall voter thinks. He traces the recent eruption of such sentiments back to the Thatcher era, which destroyed Britain’s traditional industries and economic boundaries, effectively internationalising the state.

From there, he argues, it was only a small step to the “radical cultural liberalism” of New Labour: throwing open the borders and threatening the nation’s indigenous way of life. The Cameron government then doubled down on this globalist “revolution” against the better judgement of the electorate – who finally launched a “counter-revolution” by voting for Brexit and Boris Johnson.

8—“His skill was to write about modernity without seeming to personally endorse it.”

Tanya Gold could write about pavement slabs and make them interesting, so this essay of hers on Noël Coward is, of course, gilded with 24-carat brilliance.

Coward insinuated his way into aristocratic and artistic lives, first in Britain, and then in the US, where he picked up the cadences of the future, and brought them home. Soden has the testimony of every writer Coward courted. He irritated Siegfried Sassoon, who had a headache, and reported Coward “too gushing” as he “rattled brightly on”.

Aldous Huxley thought him “much nicer and more intelligent when he’s by himself than when he’s being the brilliant young actor-dramatist in front of a crowd of people”. Others were aghast, like the audience of “Springtime for Hitler”: “WH Auden had sat through The Queen Was in the Parlour (not, perhaps, the best introduction) in abject disbelief,” Soden writes. “Is it like this,” Auden wrote to a friend, quoting Eliot, “in Death’s other Kingdom?”

Elsewhere on the NS

The Met needs to be broken up. This week’s Leader article explains.

You are living in Clapham, even if you do not live in Clapham, says Josiah Gogarty. The implication of this smart piece: it is no longer possible (was it ever?) to be cool.

Could the SNP lose Scotland? Chris Deerin investigates.

Brilliant Freddie Hayward sketch of Boris Johnson’s last stand on Wednesday. Never has “Big Dog” lacked so much bite.

Andrew Marr, our political editor, also thinks Johnson’s appearance this week shows “he has lost his old magic”.

Things are looking up, suggests James Meadway. Only joking. Things are looking terrible: “We are being marched into an economic polycrisis of financial failure, soaring inflation and recession.” What makes Meadway a compelling writer is that he comes to the party with solutions to all of these problems, rather than just descriptions of them.

“In the years of the culture wars, the 1850s have never seemed closer.” Robert Colls is an eloquent guide to the American South, past and present.

Best of the Rest

Bloomberg: After the banking crisis, a new chapter of capitalism.

WSJ: It’s not just Credit Suisse – all of Switzerland needed rescuing.

NYT: DeSantis’s secret theory of Donald Trump. It’s not “Trump was a good president”.

Wired: Brandon Sanderson is your god. A very funny profile.

Megan Nolan: Trash like this.

Sean Thor Conroe: Emmanuel Carrère’s writing life.

Bill Gates: The age of AI has begun. Big talk here.

Musa al-Gharbi: How to understand liberal sadness.

Sam Adler-Bell: Janet Malcolm’s dangerous method.

Matthew Gasda: The right-wing crusade against Shakespeare.

Xi Jinping’s KFC. US soft power remains undiminished.

And with that…

Troublingly, we have reached the last week of March and I have not read a novel this year. (Yes, I should worry about more important things.) I looked down the scratchy list of books I’ve read since 2022 became 2023: appalling non-fiction, bland history, sharp cultural critique. Books for review, books you could not pay me to read again, and books read, above all, for utilitarian reasons. Things I feel I must know. Books to keep me in the conversation.

And not one novel. Was this unusual, or just myopia? So I spent the week (and, yes, this was probably irritating) asking almost everybody I knew if they were reading fiction. If they discussed fiction with their friends. If fiction was still the place they went to for social news. Around two people out of an exhausted 40 said yes. The others, some slightly ashamed of themselves, said no. They were all reading non-fiction too. And these were “literary people” – at book launches and parties full of other “literary people”.

We should all be reading fiction. We’re not. People always say the novel is dead. The novel isn’t dead. It’s merely irrelevant. Maybe I should force myself to read Buddenbrooks again. Until next week.

Thank you for reading. Don’t miss out – subscribe to the New Statesman and stay up to date with everything you need: from news and analysis to comment and criticism.

Whether you’re looking for a sharp blog or a finely written feature, the New Statesman has you covered. Have a good week, and catch you next Saturday.

It is not a question of ' what happened to novels?' but rather one of 'what has happened to the readers, or rather to the brains of readers?' The answer to that can largely be found in the writings of Maryanne Woolf in books such as Proust and the Squid: The Story and Science of the Reading Brain (2007, HarperCollins) and 'The Reading Brain in a Digital World (August, 2018, HarperCollins). In a recent podcast to be found on The New York Times website she discusses the pleasure of 'deep reading ' and how that is compromised by 'skimming, scanning, scrolling' associated with smartphones and computers.

Personally, I am currently re-reading 'Middlemarch' and discovering the real pleasure of 'deep reading' in a long novel.

Join us in the Common Reader Book Club Will! We’re reading Dickens next month...