The Saturday Read: Is Britain still a world power?

Inside: Putin-Xi, Freud, Murdoch, Rachmaninoff, Rawls, National Conservatism and the "new ideal male".

Good morning, and welcome to the Saturday Read, the New Statesman’s weekly guide to the very best writing on ideas, politics, books and culture. This is Will Lloyd. Harry has posed this week’s question in today’s sign-off. We have eight pieces up front from the New Statesman, 15 links to pieces from across the media, and then a handful of other NS articles you might like. If you’re in Cambridge today, the New Statesman will be out in force at the city’s 20th annual Literary Festival.

This week, Harry wants to know what you think Britain’s role in the world is, or should be. When he asked me this question over a (long, journalistic) lunch, the first thing that came to mind was John Milton. “Let not England forget her precedence of teaching nations how to live.” England went on to have a long and controversial career in testing out Milton’s assumption. It took a few centuries for the English to realise, or be forced into the realisation that other nations didn’t care for its tutelage.

If the pieces below interest you, you could try a trial subscription to the NS. Read three free articles after registering on the New Statesman site. A digital subscription is just 95p a week. Let’s get to it.

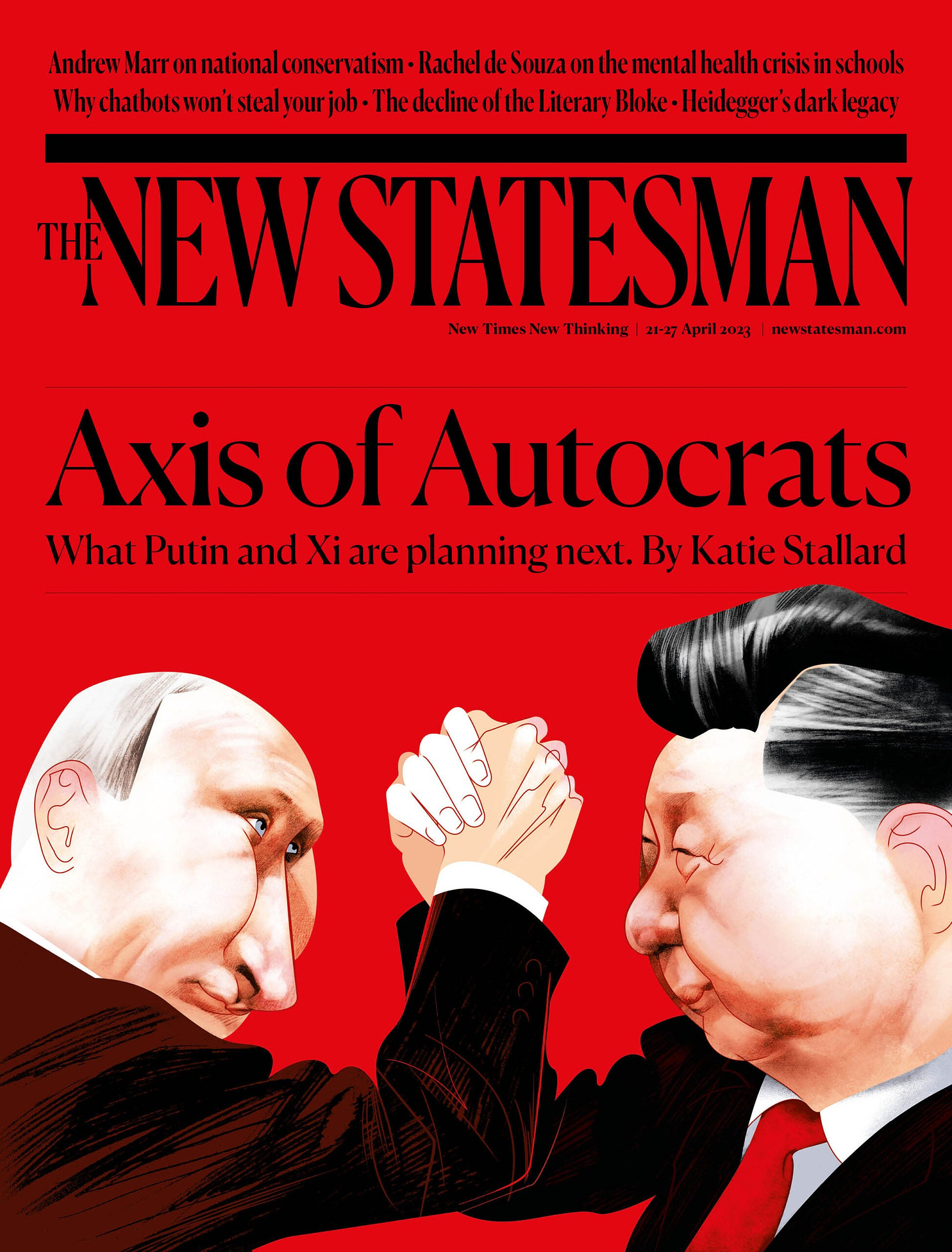

1—“To paraphrase the former British prime minister Lord Palmerston, no country has eternal allies, only interests.”

The great thing about this Katie Stallard feature on Putin and Xi – our cover this week – is that it gives you the history of the Sino-Russian relationship. The latest “axis of autocrats” emanating from the east echoes the relationship between Stalin and Mao, except that the balance of power is now clearly tilted in China’s favour. (Stalin, Katie tells us, once made Mao wait 17 days at a country house outside Moscow before he granted him a second audience after lecturing him on how to run a nation in their first meeting.) You can also listen to Katie’s piece here.

The bitter rivalry and the festering grievances that have since been unearthed about the Sino-Soviet alliance, including Mao’s fury at his treatment in Moscow, were not always apparent to Western policymakers at the time. In Washington during the early decades of the Cold War, US officials tended to group the two powers together as part of a communist colossus, and it was not until they openly split that the US understood the extent of the acrimony between them. It is important not to make the same mistake now and buy into the hyperbolic claims on both sides about the strength of their partnership.

Yet over the past four centuries, Russia and China have learned to value each other as neighbours and to understand the risks of falling out. Now, confronted with a common external enemy, both believe it is in their interest to manage their differences and maintain mutually beneficial ties. “Even if Putin dropped dead today, or Xi disappeared from the scene,” Sergey Radchenko of John Hopkins tells me, “I do not see the next generation of Russian or Chinese leaders changing course.”

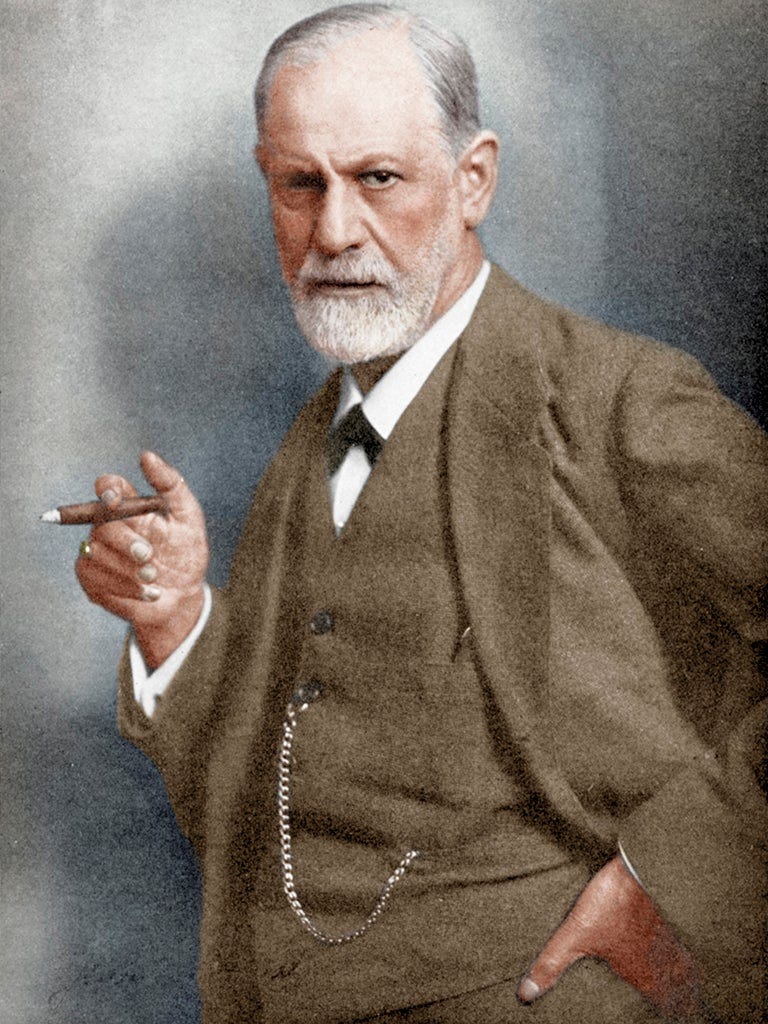

2—“It is difficult to take psychoanalysis seriously.”

Sigmund Freud liked to compare himself to Sherlock Holmes. The latter was a fictional detective, the former was a detective who invented fictions. In this review essay, the neurosurgeon and author Henry Marsh delves into Freud’s wonderfully warped world:

I found my parents’ copy of Freud’s masterwork The Interpretation of Dreams. Freud wrote extremely well, and reading it you are initially seduced by his dream stories and their interpretation. His fundamental – and completely mistaken – insight was that all dreams express wish fulfilment. In the chapter “Distortion in Dreams” he confidently explains away, with convoluted inventions, the fact that so many dreams are nightmares, filled with anxiety. How can they possibly express wishes?

3—“I had lots of time. I was stuck in bloody England.”

Me, powerful? Rupert Murdoch played the innocent again in his Dominion Voting Systems deposition this week, as Fox News settled for $787.5m with the company whose tech was used to count votes in 28 states during the 2020 presidential election.

Anyone who watched Murdoch’s testimony before the House of Commons select committee tasked with looking into allegations of phone hacking in 2011 will recognise the playbook. But how did Murdoch’s Fox News end up being sued for its election lies? It can be hard, as Murdoch’s private emails showed, to contain the corrosive culture you create.

On 11 January Anne Dias, a board member, emailed both Rupert and Lachlan Murdoch to say that, because Fox had become a “megaphone for Donald Trump, directly or indirectly, I believe the time has come for Fox News, or for you Lachlan to take a stance”. Lachlan responded by emailing his father twice to suggest they should discuss. He signed the first email “Love you”, and the second “Xx”. Murdoch responded: “Yes. Just tell her we have been talking internally and we intensely [sic] along these lines, and Fox News, which called the election correctly, is pivoting as fast as possible. We have to lead our viewers which is van [sic] not as easy as might seem.”

4—“I cannot cast out the old way of writing, and I cannot acquire the new.”

Did Rachmaninoff change music, asks Leah Broad, by refusing modernity – or accepting it?

A train screams through a station, billowing steam as it shoots past the platform in a flash of paint and steel. As it disappears into the distance, the opening chords of Sergei Rachmaninoff’s Second Piano Concerto begin – expansive, powerful, and sombre – the piano sweeping like a pendulum through the orchestra. This is the start of David Lean’s 1945 film Brief Encounter, about a doomed love affair between two married people who meet by accident and agree to part rather than tear their lives and families apart. Throughout the film, it’s left to Rachmaninoff’s music to tell us how they are feeling. The concerto encapsulates their longing for what cannot be; this is music of exquisite, all-consuming, passionate and impossible emotion.

5—“On both left and right, ‘liberal’ has become an insult, aimed at anyone who strives for consensus or objectivity in public life.”

A scrupulous reading here from William Davies of Daniel Chandler’s much-hyped new book Free and Equal. Heavily blurbed by everyone from Zadie Smith to Stephen Fry, Free and Equal aims to restate the ideas of John Rawls’ A Theory of Justice for an age that is increasingly sceptical of the American philosopher’s liberalism.

If A Theory of Justice lacked any clear sense of an enemy in 1971, the same can’t be said in 2023. How to defend liberalism in the age of Suella Braverman, Elon Musk, Facebook, millennial socialism, Viktor Orbán, Brexit and so on?

There is a post-2016 subgenre of books that rise to this challenge, including How to Be Right by James O’Brien and How to Be a Liberal by Ian Dunt, by meeting cultural fire with fire, after the rash of liberal pessimism that accompanied Donald Trump’s victory and the Brexit vote. And yet Free and Equal is neither polemic nor diagnosis. Instead, it starts from the rather unusual premise that a single philosopher holds the answers to how we should organise our society. A more commercially ruthless editor might have slapped an Alain de Botton-esque title on it such as How Rawls Can Change Your Society.

6—“By my reckoning there are, broadly, three drivers of my friends’ eccentric affection for this progressive Potemkin.”

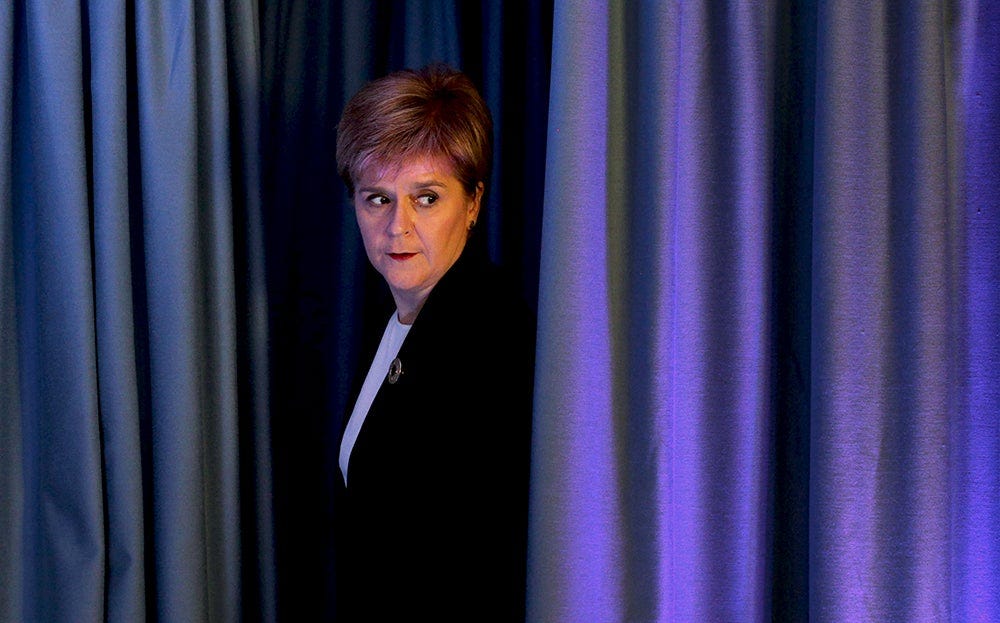

How – asks Jim Murphy, the former Scottish Labour leader – did progressives ever fall for the SNP? It’s useful to remember quite how excessively Nicola Sturgeon was praised by journalists when she stepped down on 15 February (with Robert Peston lauding her resignation statement as “truly remarkable”). Now, her party fears, she faces arrest.

Never have so many progressive op-eds been written in praise of such a superficial government. Not even stats revealing that Scots live shorter lives than people in any other UK nation, or that Scotland suffered the greatest fall in well-being out of any OECD country, seemed to trouble these new converts to the SNP’s faux radicalism.

As Scotland plummeted down the global education tables, the government responded in a way that no progressive force ever would – rather than addressing educational inequality, it simply stopped sending data and withdrew from international indexes. And what did these progressive warriors make of it all? I lost count of the times they fell back on “but the Tories are even worse, Jim”, as if that was the limit of our ambition.

7—“The tone is of a defiant Tory revolt against, presumably, whatever bloody useless government’s been in power for the past 13 years.”

In Westminster, writes Andrew Marr, Conservatives are already gearing up for the battle to define the party after the next election. On one side liberal Conservatives. And on the other, something new and more radical, the “National Conservatives”.

National Conservatism also comes with a fiercely illiberal social agenda and tinges of authoritarianism that would – certainly, should – make many Tories quail. (Meanwhile, a recent Reform UK rally gathered under the banner of “Let’s Make Britain Great” and heard speeches about white pride and the traditional family.) Hungary’s Viktor Orbán has been hosted by the National Conservatives, as has Tucker Carlson of Fox News. Is Rishi Sunak entirely happy with this new alliance?

8—“Real-world relationships and romantic comedies alike need a little more tension – an intellectual, interpersonal tension as well as the sexual kind – to stay interesting.”

Anna Leszkiewicz outlines the new male ideal, as derived from Curtis Sittenfeld’s newly released Romantic Comedy. If Sittenfeld is writing a romcom for grown-ups, then what is the grown-up fantasy of the romantic hero?

He’s in his mid-30s, a “cheesily handsome” celebrity conscious of his own status as cheesy. He is “muscular, but not too muscular”, aware his relationship with exercise is “compulsive”. He finds your insinuation that he’d only date models offensive. He has been sober since his early twenties, but doesn’t mind if you drink in the house. He asks questions like “What makes a romantic comedy non-condescending and ragingly feminist?” with total sincerity, and listens to your answer.

He listens to everything you say, actually, often making quips that refer back to comments you’ve made, or your liberal use of the word “actually”. He listens to feminist folk-rock songs, and sings them to you. He has been to a Black Lives Matter protest – although not in a performative way. He is appropriately therapised, but sometimes fears he sounds like he’s had too much therapy. During sex he says things like “Is this OK? Do you need anything?” Afterwards, he says things like, “You’re so terrifyingly, awesomely perceptive.” Best of all, he cures you of your smartphone addiction.

Best of the Rest

The Hill: Trump’s soaring fundraising

FT: The farmers challenging the EU’s green agenda. More vicious protests to come.

OpenDemocracy: Starmer’s continuing purge of the Labour left

Guardian: Taiwan expects war in 2027. Could we just not do this?

Lauren Larson: Texas vs the wild hogs

Anton Jager: Tár’s suspended judgements

Lauren Oyler: On the Goop cruise. One of the essays of the year so far.

Patrick Maguire: Starmer forgets leadership is not the law

Christian Lorentzen: Literary culture is in decay

His Majesty’s fitness regime. Charles will be flexing his orbs next month after this workout plan.

Elsewhere on the NS

Geoff Mann takes Peter Frankopan to task for being more interested in volcanoes than capitalism.

Kai Heron, Alex Heffron and Rob Booth explore the steady impoverishment of Britain’s farmers: “Last year, for instance, supermarkets announced record profits while on average farmers received less than 1p for every block of cheese or loaf of bread sold, and a shocking 29 per cent of British farms failed to make any money at all.”

Sigrid Rausing insists that “identity” was not on the minds of the judges who put together the 2023 Granta Best of Young British Novelists list.

Lamorna Ash is bewitched by a 2001 Toyota Corolla.

Sophie McBain has interviewed a psychiatrist, Joanna Moncrieff, who thinks antidepressants are useless. (People who have found them to be effective may bristle at that, but it’s an interesting read.) Moncrieff compares antidepressants to alcohol, although I’m not quite sure I’d describe alcohol as useless.

Tim de Lisle reflects on the passing of newsprint.

Ido Vock, our Europe correspondent, has written the piece I’ve been seeking on Brazil’s close relationship with China.

And with that…

Britain’s role in the world is something Dominic Raab, our newly departed deputy prime minister, was once charged with advancing. Raab, as British foreign secretary during the evacuation of Kabul in 2021, showcased how irrelevant proclamations about our global role can be. When it mattered, Britain did not live up to its self-professed values, or its own perceptions of competence.

Events and our reaction to them are what reveal our place in the world – not the statements of politicians and strategists. Just as you can judge a society’s morals by its tax code, so too you can judge a country’s place in the international order by its record of action. After the ignominy of Kabul, and the contortions of Brexit, Britain was among the first to arm Ukraine; it has reinserted itself in the defence of the Pacific through “Aukus” as a supplier of submarines; and it has, at least for now, resolved the more pressing consequences of Brexit in Northern Ireland through the Windsor framework.

But critics of our post-Brexit role remain. Jonathan Powell, Tony Blair’s chief of staff in Downing Street, told me in 2021 that we can’t, as many strategists like to imagine, be a “convener” of nations outside of the EU (“We’re too small. Why is anyone going to want to be convened by us?”) or a power in the Indo-Pacific (“No matter how many aircraft carriers we send to the South China Sea. We’re not going to be an Asian power”). Ultimately, we will act in the slipstream of American foreign policy, as we have almost always sought to do since 1945. But should we “just fall back and guard Dover”, as Tom Tugendhat once quipped? Why do we still try to influence the world?

Let us know how you think Britain should act on the world stage in the comments below, or by replying to this email. What have you read that shaped your thinking on this?

Thank you for reading. Don’t miss out – subscribe to the New Statesman and stay up to date with everything you need: from news and analysis to comment and criticism.

Whether you’re looking for a sharp blog or a finely written feature, the New Statesman has you covered. Have a good week, and catch you next Saturday.

Since the early 1900's we have slowly but inexorably been forced off centre stage by the rise of new and more powerful actors. We do have a bit part to play, both as a salutary lesson in what not to do (e.g. Suez, Iraq, Brexit) and also as an example of ceding power to the USA as the new emergent dominant world force of the 20th Century, without both sides having to resort to conflict.

We can play our now more modest role with confidence, but only if we stop pretending that we are still the leading actor on the stage. We have much to offer, but cardboard cutouts of gunboat diplomacy (e.g. aircraft carriers with no aircraft off China) or jingoistic posturing in our relationship with the EU will not permit us more than an occasional bathetic walk-on as the tedious, irritating neighbour the main actors must all live with, but mostly ignore.

We have an enormous amount of talent in the UK - most of it stifled by a succession of inept governments. If we can appoint some truly inspirational and transformative leaders, we can assuredly strut our diminished but vital corner of the stage, knowing that other more significant players hold us in the highest esteem.

If Britain is to renew its expectation of having any significant influence on world affairs it can only do so in the context of its relationship with either Europe or the USA. On its own it is too small, economically weak and badly governed to regain its past influence. As for the USA, its present status as a fairly rapidly failing democracy (though not yet as a failing state) makes it an increasingly untrustworthy and unreliable partner. Europe, being on Britain's doorstep, wealthy and democratic, is the sole logical choice for any meaningful partnership. For example Britain's puny efforts at negotiating trade agreements with Australia clearly demonstrates the limits of British influence .