The Saturday Read: What’s the story?

Inside: Sally Rooney, Tom Wolfe, Paul Gauguin, Nigel Farage, Lebanon, and the new media barons

Good morning. Welcome to the Saturday Read, the New Statesman’s guide to politics, culture, books, and ideas. This is Jason, with Finn, Nicholas and George.

Since his election victory on 4 July, Keir Starmer has had a lot to say about the mood in the country. “There is a weariness in the heart of the nation,” he said in his first speech as Prime Minister outside 10 Downing Street, and it would be his self-appointed role to lead us on a “rediscovery of who we are”. At the New Statesman summer reception, a few weeks later, he warned of the rise of the nationalist populist right, as if he had a presentiment of the troubles to come. And, indeed, as Starmer well knows now, when sorrows come, they come not single spies, but in battalions.

In the aftermath of the riots, in what is now referred to as his rose garden speech in Downing Street, Starmer spoke of a “societal black hole” and a “deeply unhealthy society”. He gloomily promised that things would get worse before they got better, a reversal of the old liberal-optimistic Blairite mantra. None of this is cheering and already the Labour cabinet, apart from Wes Streeting and David Lammy, the Foreign Secretary who spends most of his time out of the country, are being caricatured as grim GDR-style apparatchiks. “I don’t want to be the fun police,” Streeting hit back in an interview with us this week.

The question for Starmer then, as we ask on the cover of the magazine, a special issue to coincide with the Labour Party conference in Liverpool, which starts tomorrow, is: What’s the story? If narratives shape politics, what is the story Keir Starmer wants to tell about Britain? What kind of story will he craft in his conference speech on Tuesday about the country he aspires to lead on “a rediscovery of who we are”?

It’s fair enough (and good politics) to blame the Tories for Labour’s dire inheritance. But without the ability to tell a story about the country he leads, what he wants for it, and where he will take us, Starmer will continue to be at the mercy of events, in power but not in control of the narrative of his government as recent days have revealed. Talking about “delivery” is not enough, especially when he also speaks so readily of weariness and societal sickness. For all his good intentions, the Prime Minister remains a storyteller in search of a convincing story and Labour risks squandering the good will that greeted its resounding victory little more than two months ago.

The picks…

Good morning, Finn here. Here is a selection of some of our favourite pieces this week, from across the magazine and the website. Josh Glancy gives us the inside track on the crisis at the Jewish Chronicle, John Banville gets into the weeds on Goethe’s Faust, and – in my pick of the week – Lola Seaton takes on the Sally Rooney phenomenon. Nick signs us off with a dispatch from Reform’s party conference. As ever, thanks for reading and have a great weekend.

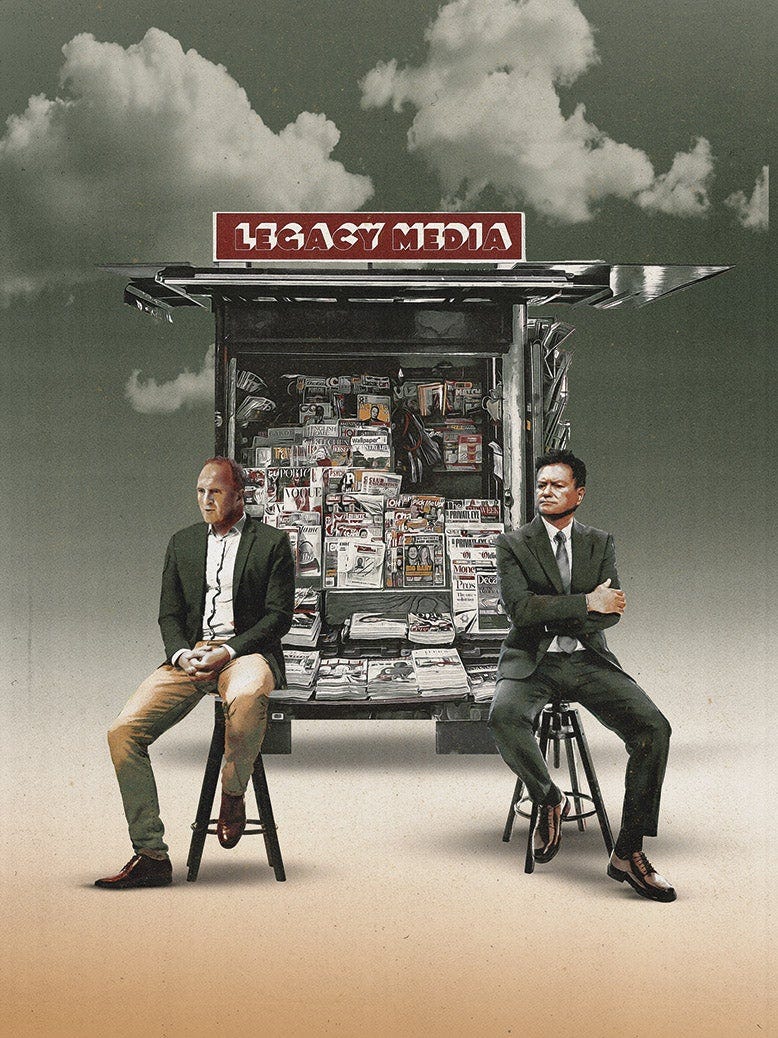

1—“The new media barons”

The Observer was founded during the French revolution, one day before Mozart’s death. Now it seems the old Sunday paper is about to meet some history of its own. It’s been a dizzying few weeks in British media, but Will Dunn is on hand to clear things up. GM

The buying up of legacy media by new entrants is part of a pattern repeated elsewhere around the world. It has happened to a much greater extent in the US, where the Washington Post, the Los Angeles Times, the Atlantic and Time magazine are among the publications bought by wealthy owners from outside the news industry.

As a new generation of media barons buys up some of the bastions of the legacy media, it is vital that we ask what these people really represent, and whether they will keep alive the industry of speaking truth to power. As we have seen from Elon Musk’s takeover of Twitter and Donald Trump’s attempts to grow his own echo chamber, the media is far from waning in power – to some, it has never been more valuable. It is also crying out for investment. Whether you buy a paper or not, the outcomes of these bidding wars will affect us all.

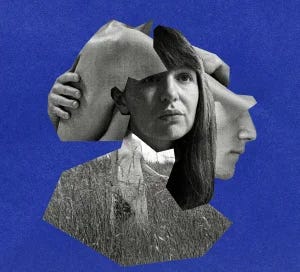

2—“Closer to something that someone else might have written.”

Is this the most anticipated book this year? It’s certainly up there. The internet is already flooded with reviews of Sally Rooney’s Intermezzo, X is groaning under the weight of takes. But you will not find any essay more comprehensive, commanding and perceptive than Lola Seaton’s. FMcR

What makes Intermezzo better than its predecessors is what makes it more imperfect: it is Rooney’s most wholehearted novel but also her most sentimental; her most uninhibited but not her most compulsive; her most likeable but not her coolest; her most highbrow but not her most accomplished. The book is sprayed with references to classical music – the source of its Italianate title – and literary borrowings, itemised in an appendix. The greatest gain that is also the greatest loss concerns its style. Though heavily stylised, Intermezzo is not a stylish book. Its conspicuously average, headlong first sentence – “Didn’t seem fair on the young lad” – is mainly remarkable for its contrast with the impassive poise we’ve come to know. This was already on its way out in Beautiful World, in which Rooney took her aloofness to artificial extremes, turning an effective style into a gratuitously distant manner.

3—“Scenes like a horror film.”

Hanna Davis writes from Beirut, a city in chaos after two waves of breath-taking attacks by Israel. The day after the first attack, as Lebanon reeled from thousands of handheld pagers exploding simultaneously, walkie-talkies began to explode too. Davis provides a close account of these unbelievable events. GM

Sirens roared through Beirut, as ambulances rushed victims, many with missing eyes and hands, to hospitals in the Lebanese capital. Nearly 3,000 people were injured on 17 September and 12 killed. While the pagers were owned by Hezbollah members, there were no guarantees who was holding the device at the time it was detonated. The Associated Press reported that some who used the pagers were also members of the group’s civilian operations, including doctors, nurses, teachers, and charity workers.

4—“I think they’re appalling, I really do.”

George’s interview with Health Secretary Wes Streeting has taken off across the media this week. Streeting is a uniquely interesting minister: he is its most assured communicator and, because he presides over an election-deciding issue, one of the few who can walk into No 10 and make real demands. GM

Nearly a decade after he entered parliament, Streeting is invariably described by both admirers and detractors as a “Blairite”. How does he feel about that label? “Well, hopefully off the back of the choices we make, we’ll have our own labels by the end of this government,” Streeting quipped. He added that while he admired Tony Blair’s three general election victories and record of public service improvement, he also has points of disagreement. “My critique of Tony’s leadership, beyond the obvious of Iraq, which I didn’t support at the time, is that he was too quick to declare a classless society, and even in his response to the Grenfell Inquiry I thought he missed one of the central lessons of what was a genuinely distressing and jaw-dropping report, which was a story of working-class people being ignored by professionals in power and treated like their voices didn’t matter.”

5—“Reveal us to ourselves.”

How did “the first great modern work of literature” come to be? In some ways Goethe’s composition of Faust is almost as epic as the work itself. John Banville discusses the great man’s great play. GM

To an uncommon degree, Goethe was what he did; as Faust himself declares, “In the beginning was the deed.” As Wilson is at pains to emphasise, Goethe did not regard himself primarily as a poet, much less as a dramatist. His greatest work, he believed, was his scientific treatise on colour, which was intended, not to confound Newton’s theories on optics, but to expand them and to humanise them.

To enjoy our latest analysis of politics, news and events, in addition to world-class literary and cultural reviews, click here to subscribe to the New Statesman. You'll enjoy all of the New Statesman's online content, ad-free podcasts and invitations to NS events.

Our investments in both the North Sea and in developing new lower carbon energy projects help to support the UK economy. bp spent £5.3bn with UK suppliers last year and contributed an estimated £17.1bn overall to the UK’s GDP. See how bp has been backing Britain.

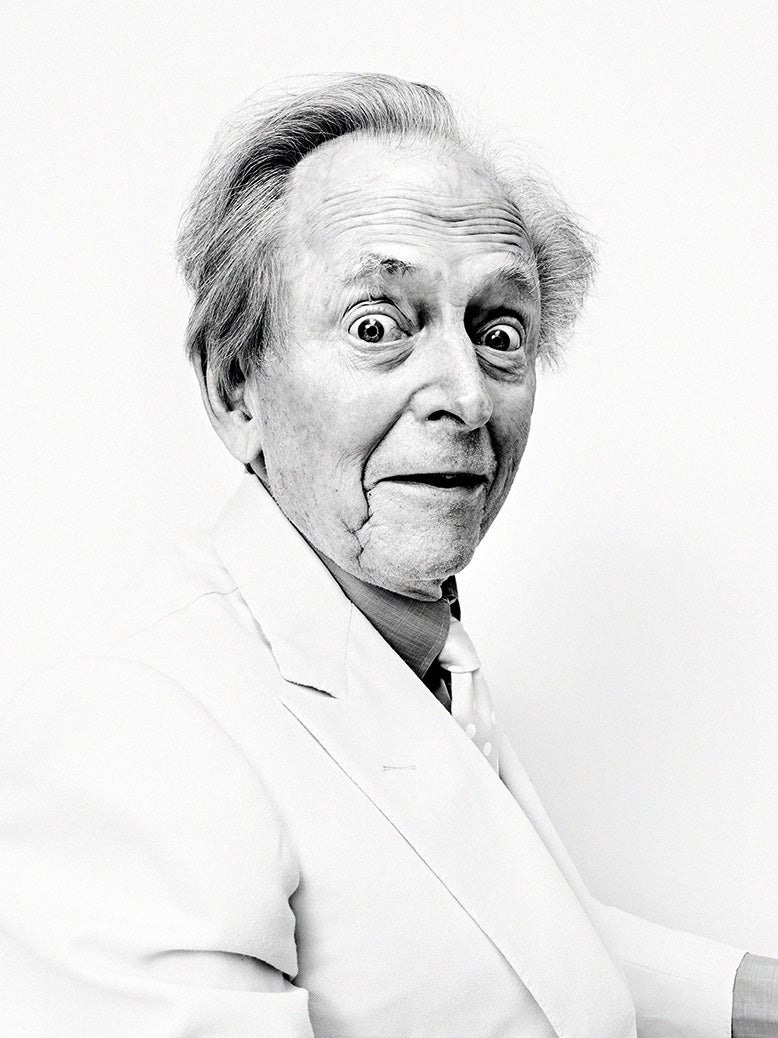

6—“The acid aesthetic.”

Psychedelia is a tolerated, integrated part of our culture now, but in 1968 it was Day-Glo new. Fifty years after its publication, Geoff Dyer revisits the best account of its arrival, Tom Wolfe’s The Electric Kool-Aid Acid Test, a unique convergence of the right characters (Ken Kesey, Neal Cassady), the right drug (LSD), and the right reporter. NH

What do we expect from The Electric Kool-Aid Acid Test now, more than half a century after it was first published? Back in 1968 the story of Ken Kesey’s Merry Pranksters and their attempts to spread the gospel of LSD was not exactly breaking news – it had not, as the saying goes, been torn from the screaming headlines of today – but Tom Wolfe’s book expanded the reach of the Kesey project to an audience who’d not enjoyed the mixed blessings of encountering the Pranksters or sampling their unusually potent wares. It’s possible that even some of those who could answer the question posed by Hendrix’s first album – “Are you experienced?” – in the affirmative weren’t aware of the backstory. Today we read the book partly because the broad outline of that story is now well known.

7—“Jewish history has particular capacity for repetition.”

After publishing a series of thrilling (and unfounded) scoops from a journalist who was not who he said he was, the Jewish Chronicle is in crisis. No one better than Josh Glancy – a former JC columnist – to take us through the scandal. FMcR

Jonathan Freedland, who has written for the JC since 1998, wrote in his resignation letter, which he shared on X: “Too often, the JC reads like a partisan, ideological instrument, its judgements political rather than journalistic… The real problem in this case is that there can be no real accountability because the JC is owned by a person or people who refuse to reveal themselves.” Newspapers are powerful instruments, and most have carefully organised management structures, with proprietors facing reputational consequences for any wrongdoing. While the Independent’s ownership by the Saudi Research and Marketing Group, which has ties to the Saudi royal family, caused concern, no other British newspaper’s ownership is an actual secret. It means the proprietor of the JC is not answerable to its readers – or the public – over the startling lack of due diligence done on Elon Perry.

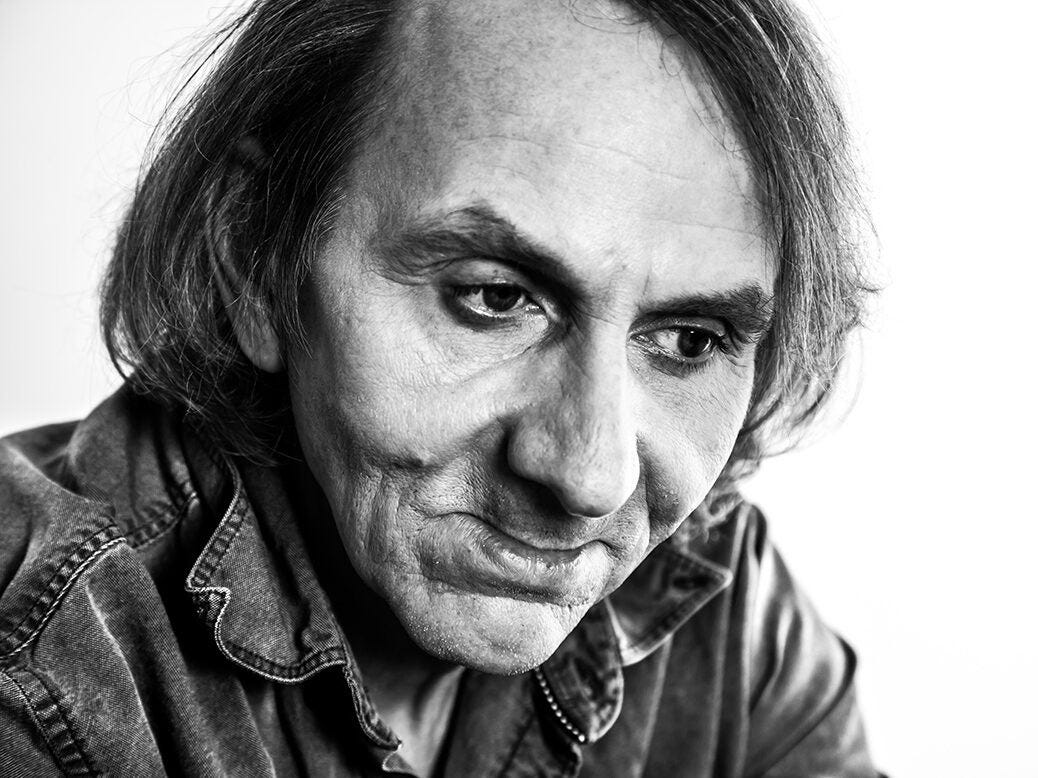

8—“Michel-mania has been and gone.”

After an extraordinary period of cultural centrality for a modern writer, Michel Houellebecq’s status and novelistic powers are on the wane. Rob Doyle bids something of a farewell to the Houellebecq era – and wonders if we actually had him wrong all along. NH

Michel Houellebecq once wondered whether all he has done as a writer has been, like his beloved H.P. Lovecraft, to fashion “materialist horror stories” from the chaos of the world that came to disappoint Kandinsky’s vision. And that is what his novels are – from one perspective. The afore-quoted passages, and others like them, tempt us to wonder if, all along, Houellebecq was really writing, or at least longed to write, an entirely different kind of story.

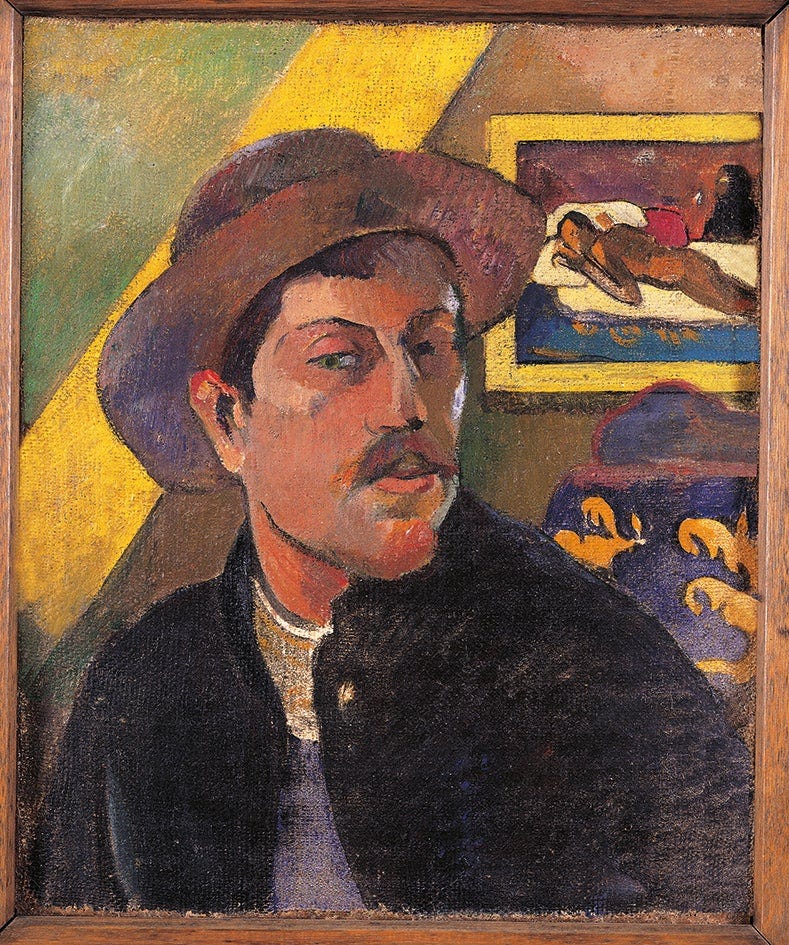

9—“Prudence had no place in his art.”

Tales of great artists who happen to be total monsters seem to be ten-a-penny. It’s always nice when someone comes along to remind us that the world – and art – is a lot more complicated than that. Michael Prodger shines a light on Paul Gauguin, concluding that within the wretchedness there was “a rich seam of nobility.” FMcR

For all Gauguin’s admiration for the Impressionists he never adopted their short brush strokes, their devotion to capturing rapidly changing nature or their scientific understanding of colour. He was touched with synaesthesia, so colour for him carried emotion. It meant, for example, that during the intense and ultimately tragic nine weeks he spent living and working with Van Gogh in Arles in 1888 he understood that the yellow of the Dutchman’s sunflowers carried the painter’s aspirations and personality too. In Polynesia he sent to France for packets of sunflower seeds to plant in memory of his one-time friend.

10—“Anything but conservative.”

We all recognise and love The Planets, but Gustav Holst is not a one hit wonder. Simon Heffer takes us beyond The Planets and into the deeper galaxies of the great composer’s genius. GM

If all one knows is The Planets, one knows only a little about Holst’s talent, and therefore about his greatness. He wrote numerous smaller orchestral masterpieces, including remarkable representations of places and landscapes. He was a master of the art song. He, with his close friend Ralph Vaughan Williams, drew deeply on the tradition of English folk song to try to create a distinct, benign national style of music. He wrote choral works of power and distinction. He cast off an early, and in his generation typical, devotion to the 19th century German masters not just to find an English voice, but to imbibe the influence of Indian and Middle Eastern music. He tried his hand, somewhat successfully, at opera and ballet, and there was copious chamber music. Had he not died comparatively young – at 59, suffering heart failure after an operation – he would have finished another symphony (he had completed a choral one, and early in his career a thematic one about the Cotswolds), of which only the Scherzo was finished.

11—”The old orthodoxy has broken.”

Keir Starmer is currently preparing for the first conference speech delivered by a governing Labour leader since 2009. And, Phil Tinline writes, if he can find the right words to sway the nation, he can ensure 2024 is remembered as a political turning point akin to 1997, 1979, or even 1945. NH

The prime ministers who have created enduring, transformative governments – like Thatcher, Blair and Clement Attlee – were those who saw past the daily whirl, and noticed the deeper forces that were reconfiguring the world. They recognised how the patterns of hope and fear that shape the electorate’s priorities were already starting to change. And they found a way to turn that into a compelling narrative: a story of how what had once been unthinkable was now not just possible, but unavoidable.

George’s Best of the Rest

Jackson Arn: The anguish of looking at a Monet

Christopher Bonanos: Robert Caro toils on

Wendy Brown: Marx explains the world

Cook, Jennings: Scenes from the literary blacklist

Kara Kennedy: Chappell Roan makes sense

Mark Lilla: Is ignorance bliss? I dunno!

Katie Ward: Everything my mentor Hilary Mantel taught me

Cinnamon the capybara is “living best life” on the run from Shropshire zoo

And with that…

I have the good fortune of writing to you this morning from the Birmingham Airport Holiday Inn. This isn’t where I choose to holiday: my temporary residence abuts the city’s National Exhibition Centre complex, part of which has been taken over by Reform UK for their annual conference. You can read my report on day one here, but on a personal level it has been a weekend of firsts: my first party conference, my first encounter with Nigel Farage, my first face-to-face with the mighty, smirking slab of Lee Anderson.

How would you know it’s a Reform conference? By the ample smoking terrace? By the dedicated Pravha pilsner bar? Or perhaps by the signs forbidding attendees from purchasing more than four alcoholic beverages at a time? Conservative Party conference will be dominated by its uninspiring leadership contest; Labour’s by dodging questions about who sourced its speakers’ suits, frocks and spectacles. By contrast, Reform are here to luxuriate in their general election performance, and to drink to what they promise is an even brighter future (chairman Zia Yusuf sent shivers down my spine when he referred to “prime minister Farage”). Whatever you can say about momentum in politics, it says something that people have come here with the intention of having a good time.

— Nicholas

The New Statesman is home to the finest writing on politics, culture and ideas. To stay up to date, subscribe using the link above.