The Saturday Read: Which book changed your life?

Inside: Our new financial masters, Tory rule, bad men, Pre-Raphaelites, ballet, and a guide to China.

Good morning, and welcome to the Saturday Read, the New Statesman’s weekly guide to the best writing on ideas, politics, books and culture. This is Harry. Along with our usual mix – essential NS reads and links to pieces elsewhere – we have some new sections for you in today’s email.

Has a book, asks Will in today’s sign-off, changed your life? I mentioned one a few weeks ago that changed mine: The Fall by Albert Camus. I’d taken it from my grandmother’s shelves for the long flight home from South Africa. It was mercifully slim, as Camus’ novels often are. Open it and a vital, loquacious narrator will start addressing you. You’re with him in a bar in Amsterdam, being ordered gin and told the story of his social downfall (but spiritual ascent?). He was a great figure in the swim of things once, a lawyer of renown in Paris. Then something happened. The hypocrisies under which he was living – under which we all live – imploded. The Fall is an ice bath in reality.

If today’s pieces intrigue, you could try a trial subscription to the NS. Read three free articles after registering on our site. A digital subscription is just 95p a week. Let’s get to it.

1—“What we do is behind the scenes. Nobody knows we’re there.”

Asset managers, financial firms who invest vast sums on behalf of pensions funds and insurance schemes, have diversified away from shares and bonds in recent years, and came to control much of the physical world around you, unbeknown to most of us. Brett Christophers details how they came to wield power by buying up housing and infrastructure across Britain and the rest of the world. (Far from seeking to change that, Keir Starmer and Rachel Reeves have reportedly been conducting a “charm offensive” with senior executives at Blackstone, Brookfield and other leading asset managers, Christophers notes.)

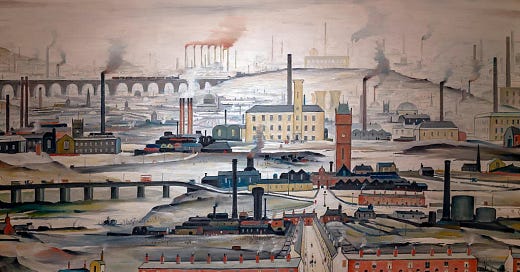

Asset managers own, and extract income from, things – schools, bridges, wind farms and homes – that are nothing less than foundational to our being. Forty years ago, it would have been unthinkable that we would buy our gas from, make our parking payment to, or rent our home from a company like Blackstone. But this is the new reality.

In a very physical, if also strangely intangible respect, all of our lives are now part of asset managers’ investment portfolios. Arguably, this is truer in Britain than anywhere else. Consider the quiet county of Kent in south-east England. The entire infrastructure of wastewater collection and treatment in the county, including tens of thousands of kilometres of sewers, is controlled by Macquarie, a leading Australian asset manager… Quietly, without attracting much attention, asset managers have colonised Kent’s built environment, stitching themselves into the very fabric of the region’s social metabolism.

2—“Take the longest view and the picture becomes clear. Britain is a one-party state. A Conservative nation.”

Why do the Tories have such a hold over Britain? Picking up on a question we asked recently, Will reviewed two new books that seek to answer that conundrum. Does the Conservative Party have a better grasp, Will wonders, of how British people feel in their bones than left-wing parties do?

Unlike Labour, the Tories have always grasped the darker side of Britain. The nation that hymns the NHS, but would like to birch criminals. A populace that gives millions to charity, but also includes many who would like to close the borders. Citizens who are at once kindly and decent, as well as suspicious and cruel. Understanding this, whether consciously or not, has been critical to the Conservative Party’s success. Labour only wins when it acknowledges the country it is competing to lead. As such, when it does win, Labour will govern on Tory terms.

3—“Should one, say, stop releasing Woody Allen films? Stop screening them? Stop streaming them? Or perhaps, even, stop liking them?”

Ann Manov addresses the “art monster” problem. What should we do about the works of men who turn out to be moral failures?

One might think it safer to keep a predator away from film sets, or see a capitalist logic in shrinking their royalties, but in many circles even fandom has come under fire. To say one likes Annie Hall, let alone Manhattan, sounds like a dog whistle. Yet it isn’t obvious why: is the work supposed to be a moral reflection of the creator? Is admiration or enjoyment of a work a sign-off on some misogynistic subtext? What, after all, is supposed to be our relationship – emotional, political or otherwise – with artists who’ve behaved badly (a category which, if we go far back enough, might encompass virtually all of them)?

4—“A global Weimar riven by new technologies and resource scarcity is our default condition.”

For our cover this week, John Gray and Helen Thompson joined the author Robert Kaplan to discuss “The New Age of Tragedy”. The outlook of geopolitics is increasingly bleak. Rather than giving in to despair, Gray, Thompson and Kaplan’s wide-ranging exchange asks how societies might navigate these gathering storms.

Today, the great powers have some things in common with the characters in Jean-Paul Sartre’s play No Exit (1944). Three dead souls find themselves in a locked room, seemingly damned for their sins. One of them tries to escape, but when the door opens he cannot make himself go through it, and all three remain stuck in the room. In a celebrated line, the failed escapee concludes: “Hell is other people.”

The great powers are trapped in a geopolitical version of Sartre’s room, a claustrophobic world from which there seems to be no exit. This is not the binary world of the Cold War. Three or more states – America, China, Russia and India – are contending for the shrinking resources of an overloaded planet.

5—“He doesn’t like talking to people, and it’s showing.”

He’s socially odd with a weak voice. He doesn’t like talking to people. How did the betting markets ever think Ron DeSantis was America’s most likely future president? Such hype has now fallen away, Katie Stallard explains. Donald Trump is the clear favourite to return as the Republican Party’s nominee in 2024. (If you’d like a reminder of what that’s going to be like, here’s a dispatch I filed from a Trump rally deep in Pennsylvania in November.)

DeSantis’s initial attempts to position himself as “Trump without the chaos” have come across more as “Trump without the charisma”. He has struggled with basic retail politics, appearing aloof in interactions with voters in early primary states. Despite travelling to Washington DC on 18 April to meet House Republicans in the apparent hope of securing their endorsement for a presidential run, several announced on the eve of his visit that they were backing Trump instead. David Trott, a Republican congressman from Michigan, dismissed him as an “arrogant guy” who is “very focused on Ron DeSantis”.

6—“He loves this place, he loves the institution, he loves Westminster.”

Freddie Hayward, our political correspondent, profiles James Forsyth, Rishi Sunak’s best man turned political secretary. Forsyth is a fixture of the Westminster village. His wife, Allegra Stratton, another journalist-slash-political-adviser, previously worked for Sunak and then Boris Johnson (Stratton famously resigned during Partygate). Both, writes Freddie, want to be in the room where it happens – now it’s Forsyth’s turn.

He’s marshalling the government’s attempt to salvage the next election, “Stop the boats” and all. He really believes in this. “He’s very Tory,” the friend notes. “He sees keeping Labour out as an important job.”

“He’s a party guy, he’s from the village,” says a former aide. Like that other journalist-turned-Tory Michael Gove, he separated with the Cameroons over Brexit by backing Leave. So did Sunak. The success of both is now more entwined than ever. The next election could determine whether Forsyth’s move into politics is permanent or whether, like his wife, he reverts to journalism. His time in No 10 will almost certainly prohibit a return to reporting. But many former aides have gone on to write columns, often from the Lords.

7—“I think there’s a fine line between being ruthless and being seen as bullying.”

George Eaton meets John McDonnell, who was probably the most orthodox Marxist who ever had a shot at becoming chancellor of the Exchequer. The Labour left’s influence on the party as a whole has been in freefall since Keir Starmer became leader. Contortions over the anti-Semitism crisis within the party continued this week, when McDonnell’s colleague Diane Abbott lost the Labour whip. Yet George raises the possibility that the left may have an unexpected influence on the direction of British politics in years to come.

The Labour left no longer controls the party’s commanding heights, yet it is far from irrelevant. Excluding three independents, the Campaign Group numbers 31 Labour MPs – nearly a sixth of the Parliamentary Labour Party. In the event of a hung parliament or a small Labour majority, it could wield significant influence.

Will McDonnell, who rebelled hundreds of times in the New Labour era, revolt if a Starmer government imposes real-terms spending cuts? “I can’t see that we’ll be in that position, but they need to know there will be widespread opposition, not just within the party but across the country. This isn’t people being threatening, it’s just saying ‘Why can’t we have a democratic, open debate and discussion?’”

8—“At times Lizzie was more than flesh and blood, personifying his idea of perfect womanhood that justified a love that transgressed social station.”

Michael Prodger, our art critic, takes us into the world of the Pre-Raphaelites, and the women who lived with and were painted by Dante Gabriel Rossetti, particularly Elizabeth Siddal, a fellow artist below Rossetti’s “social station” who he refused to introduce to his parents after their marriage.

The PRB lasted only a few years but its influence was longer lived. Lizzie Siddal was enraptured by both its headiness and the charisma of its members. Rossetti, aged 20 at the time of the group’s foundation, knew how to present himself, wearing shabby evening clothes in the daytime, and exuded both intensity and swagger. When Lizzie daringly moved in with him they began to work together, creating personal fantasies from Arthurian legend, Keats’s “La Belle Dame Sans Merci” or Rossetti’s own poem “Sister Helen”.

The exhibition suggests that Rossetti learned from Lizzie as much as the other way round but in truth it was a thin bargain: for all the potency of his vision, Rossetti was a limited artist and the untrained Siddal even more so.

Best of the Rest

Economist: Full transcript of Starmer’s interview. If you can tell us what his five missions are without Googling them we will give you a tenner.

Politico: Is it a problem that Biden is tired, old and boring?

Reuters: Peter Thiel “sick of culture wars”, won’t fund the GOP in 2024.

Katy Balls: Meet the Starmtroopers. Save yourself some time and call them “Blairites”.

Rob Madole: Norman Mailer’s ripe garbage.

Andrew Gimson: Tim Bale does not understand Boris Johnson.

Tucker Carlson: People are “really nice”. He wasn’t talking about Rupert Murdoch.

Adrian Wooldridge: The prophet of 21st-century national identity.

Elsewhere on the NS

First, our contributing writer wrote a column for the Observer about racism. Then Diane Abbott wrote a letter to the Observer, responding to Tomiwa’s column. Then all hell broke loose, and Tomiwa replied to Abbott in this week’s New Statesman. His response is the definition of killing somebody with politeness.

National Conservatism – an organised, radical American conservative movement – is holding a conference in Westminster next month. You’ll be hearing much more about the Nat Cons then – but make a start on them, and their two most influential figures, with this essay by Suzanne Schneider and Yotam Hotam.

Labour’s monumental poll lead over the Tories is shrinking, down from a peak of 29 points to 16 today. What we are seeing, suggests Ben Walker, our polling expert, “is a slow rallying of the Tory base”.

The British system of local government “is the most powerless, most dependent, most put-upon, most disregarded, most useless of any mature democracy”. Matthew Engel reports.

Richard Sharp’s resignation yesterday was “an act of kindness” from the outgoing BBC chairman towards Rishi Sunak, writes Andrew Marr.

In ballet, Pippa Bailey explains, men are “scarce but powerful”. They choreograph the work of the grandest companies and exert great control over the bodies of ballet’s many female dancers.

“I don’t do issue writing, I do character writing.” Sophie McBain profiles Judy Blume.

Sinn Féin has abandoned its “monarchophobia”, and that’s a good thing, writes Finn McRedmond.

Political theorists need to get out on the road and document reality, as Tocqueville did, argues Nick Burns.

How to get into: China

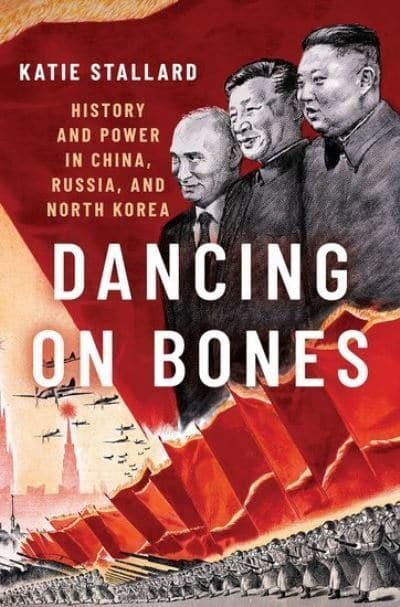

In a new feature, we’ll be asking someone to recommend three books on a subject. This week I asked Katie Stallard, our senior editor for global affairs, where to start on China.

Wealth and Power: China’s Long March to the Twenty-First Century by Orville Schell and John Delury (2013). The definitive account of how China’s history of “national humiliation” has propelled the country’s modern rise and the contemporary leadership’s claim to be making China great again.

The Party: The Secret World of China’s Communist Rulers by Richard McGregor (2010). Written more than a decade ago – before Xi Jinping came to power – but still one of the best and most enjoyable books on the inner workings of the CCP and what goes on behind the scenes at Zhongnanhai (the party leadership compound).

The Chinese Communist Party: A Century in Ten Lives edited by Timothy Cheek, Klaus Mühlhahn and Hans van de Ven (2021). A succinct and highly readable account of the history of the CCP through the stories of ten notable figures – a great overview of the party’s history and the intellectuals who shaped it.

I would also recommend Katie’s own recent book, Dancing on Bones, one of the FT’s top political books of 2022, and a definitive exploration of the way the past is being rewritten and abused by Xi, Vladimir Putin and Kim Jong Un. In the meantime you can read Katie in the NS every week, by subscribing here:

What we’re watching

Three episodes to go. Succession, as Rachel Cooke, our TV critic, once put it, is a show “as much about the absence of love as the presence of money”. I like that line. But is Roman the exception to that rule? He alone among the cast, someone suggested to me recently, loves his family, and that’s the key to the show. Is that right? In the early seasons the show’s central question seemed to be whether Kendall could become a killer. What is it now? Let us know in the comments below.

Letter of the week (“Is Britain still a world power?”)

Chris Counsell: Since the early 1900s we have slowly but inexorably been forced off centre-stage by the rise of new and more powerful actors. We do have a bit part to play, both as a salutary lesson in what not to do (e.g. Suez, Iraq, Brexit) and also as an example of ceding power to the USA as the new emergent dominant world force of the 20th century, without both sides having to resort to conflict.

We can play our now more modest role with confidence, but only if we stop pretending that we are still the leading actor on the stage. We have much to offer, but cardboard cutouts of gunboat diplomacy (e.g. aircraft carriers with no aircraft off China) or jingoistic posturing in our relationship with the EU will not permit us more than an occasional bathetic walk-on as the tedious, irritating neighbour the main actors must all live with, but mostly ignore.

And with that…

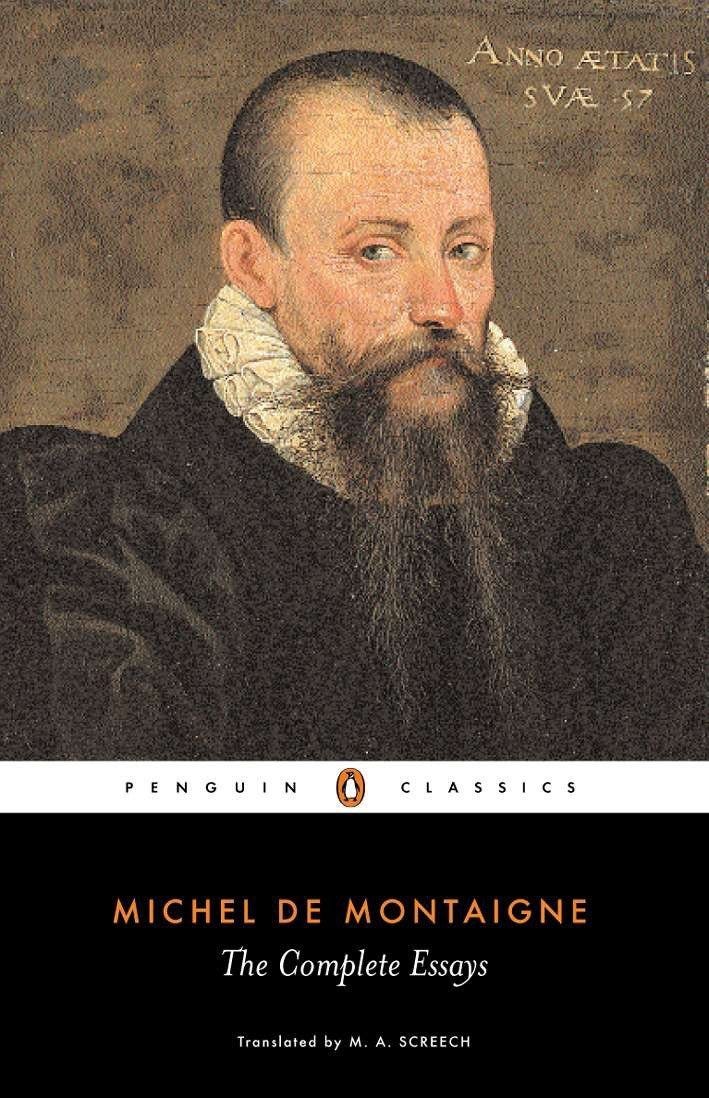

This week we want to know which book, if any, changed your life. I can recall the exact moment I encountered that book. I wasn’t in a library or a bookshop. It was 2015, I was in a rut, bored by my own thoughts, when the sound of the postman struggling with the letterbox became apparent. The package hit with a thud. I heard the book that changed my life before I saw it. The Complete Essays of Michel de Montaigne come to about one thousand pages. The bald 16th-century Frenchman in a ruff on the cover promised little. I heaved Montaigne on to my desk and began to read.

TS Eliot compares Montaigne to a fog. Virginia Woolf called him “this great master of the art of life”. Montaigne might be the only author Gore Vidal was straightforwardly enthused by. Others liken him to a friend. It is an odd experience, reading the 400-year-old words of somebody and feeling, spookily, as if they are in the room with you. That is Montaigne’s genius: he collapses time. I had not realised that I required the friendship of a French nobleman who died in 1592. Yet there it was, and still is, whenever I pick that book up again.

Thank you for reading. Don’t miss out – subscribe to the New Statesman and stay up to date with everything you need: from news and analysis to comment and criticism.

Whether you’re looking for a sharp blog or a finely written feature, the New Statesman has you covered. Have a good week, and catch you next Saturday.

Thanks to our colleague Chris Bourn on this week’s edition.

“This song will save your life” by Leila Sales was instrumental in helping me get out of my nervous breakdown at university. I’ll always be grateful to it for helping save - and therefore changing - my life.

"The Road Less Traveled", F Scott Peck'