The Saturday Read: Who is shaping the left?

Inside: Our power list, NatCon, race essentialism, 1848, Twitter, UBI, and the self.

Good morning, and welcome to the Saturday Read, the New Statesman’s weekly guide to the best writing on ideas, politics, books and culture. This is Harry. We have a fine set of pieces for you today. You can catch those below.

First, this week we brought Morning Call, our other New Statesman newsletter, over to Substack. If you would like a daily take on politics and the news, this is the newsletter for you. It is primarily written by Freddie Hayward, whose pieces have often appeared here. You can subscribe by clicking on the button below.

As ever, if the pieces below intrigue, perhaps you’d like to try a trial subscription to the NS. Read three free articles after registering on our site. A digital subscription is just 95p a week. Let’s get to it.

1—“Who are the 50 most influential people on the left?”

For the first time since 2010 the Labour Party looks like it will return to government. Who really matters on the left? The question is more urgent than it has been for a long time. This week our Left Power List sought to answer it, provoking a flood of comment online. You can dive into the list here, or find it on newsstands this weekend. We asked George Eaton, our senior editor who led the project, what stood out from this year’s names:

In a reflection of Labour’s current strength, the top three places are occupied by members of the party and 21 of those on the list are serving Labour politicians or aides. After the largest wave of strike action since 1989, we also include four trade union general secretaries in the top 20. Finally, our list testifies to the growing influence of podcasts and social media over traditional newspaper columns.

2—"An arms race of reindustrialisation is under way."

Stop raising interest rates – and invest, invest, invest. Those are Andy Haldane’s key prescriptions for the economy, offered in an interview with Anoosh that reverberated this week. Haldane, a former chief economist at the Bank of England, is a fascinating figure; Corbyn and Cummings would both have liked him to become the Bank’s governor. (He now runs the Royal Society of Arts.)

“There’s not so much as a fag paper to put between Labour and the government when it comes to fiscal rules and fiscal rectitude right now,” he told me. “That, for me, really lacks ambition at a time when it’s still, by any historical standard, incredibly cheap for governments to borrow.”

“This is not a clarion call for fiscal profligacy,” Haldane said. “I’m saying what you borrow for really, really matters. If you are borrowing today, in an investment way, to nurture public goods, assets of tomorrow – they might be clean air, clean water and a flourishing biosphere, I don’t just mean HS2 – that is an investment worth making that pays off over the medium term, well in excess of the current cost of borrowing.”

3—“This week, we may have seen the Conservative future and it does not work.”

David Gauke watched the National Conservatism conference this week so that you didn’t have to. The money and the ideology behind the event were “essentially American”, David writes, with an emphasis on faith, family and the flag. At least, he adds, we were spared advocacy of gun rights. (Look out for more on the event, and the conservative movement, from Will next week.)

The country is going to the dogs. That is the message from the National Conservatism conference and there is a long list of people to blame. People who do not have children. Unmarried people or married gay people who have children. (Not to mention people who think gay people should be allowed to get married.) Unassimilated immigrants. The godless. The cosmopolitans and the metropolitans. The free traders and globalists. Enthusiasts for the financial services and tech sectors. City-dwellers. The south-east of England. The managerial classes. The university graduates. People who don’t tweet using their real name or fail to change their child’s school to one that is less woke (yes, really).

4—“We’re part of a bigger, far grander mystery beyond our perception.”

Try this Sophie McBain interview. It might change the way you see.

He let the hedges grow thick and unruly, to better provide shelter and food for birds and insects, and rewiggled the stream to create wetland meadows and natural pools for wildlife. He ripped out the fences, sold his sheep and cows to be replaced by native longhorn cattle, and got into a spat with some neighbours for introducing red deer that promptly escaped. At the spot where Iris died, he built a granite stone circle.

“I’ve gone from someone who, like everyone else, desires the perfect life, everyone perfect and in their place, the perfect family, the perfect farm in Somerset, the perfect job… to realising that doesn’t exist, and that in fact we walk through a kind of field of imperfection,” he said. “I almost have in mind that your life is by the end a field of rubble and damage, and just littered with these perfect gemstones, and what you do is cherish those.”

5—“Black identity is a reality, not an idea.”

Tomiwa Owolade’s forthcoming book asks why Britain has allowed itself to be absorbed by so many American neuroses around identity, immigration and colonial history. In this adapted version of a lecture delivered in Cambridge earlier this May, he allowed NS readers a peak at some of his arguments against what he calls “race essentialism”:

Black American culture does not arise out of a metaphysical essence called blackness. It comes from the particular historical circumstances of black people in America. It is just as much American as it is black. Black American culture is also not a singular thing. It is plural. As Kwame Anthony Appiah puts it: “African-American identity, as I have argued, is centrally shaped by American society and institutions: it cannot be seen as constructed solely within African-American communities.

“African-American culture, if this means shared beliefs, values, practices, does not exist: what exists are African-American cultures.” Race essentialism isolates black identity from any sense of rooted context. I argue instead in favour of context over and above essentialising.

6—“Is our 1848 coming?”

Bourgeois order, writes Samuel Moyn in this review of Christopher Clark’s new history of the revolutionary turbulence of 1848, often conceals profound discontent – and revolutionary threat. Are contemporary liberals facing the same daunting choices their political forebears did in mid-19th century Europe?

As Karl Marx showed in his 1852 essay “The Eighteenth Brumaire of Louis Napoleon”, the 1848 coalition did not last, as a new Napoleonic regime emerged within a few years of the farce to which the revolution gave rise. One lesson of Christopher Clark’s magnificent new narrative of 1848 is a reminder of just how quickly liberals switched sides in throwing in their lot one more time with counter-revolutionary order.

7—“The other danger to Twitter is that most people don’t actually like being on it.”

When Elon Musk took over Twitter, he saddled it with debt, scared away its advertisers and sacked most of its staff. Now he’s conducting a volte-face by hiring the advertising industry’s “Velvet Hammer” to lure back the ailing platform’s only major revenue stream. Will Dunn reports.

Days before Yaccarino joined Musk on stage in Florida, the research company Insider Intelligence forecast that Twitter’s income from ads would fall to less than $3bn this year, a drop of 37 per cent since Musk became CEO.

At the same time, Twitter needs more money than ever before, because it was bought using almost $13bn in bank debt which incurs around $1.5bn a year in interest payments. Appointing one of the advertising industry’s most senior executives to run Twitter is a tacit admission that the company is in bad shape. But insiders say that even if Yaccarino is given a free hand, it may be too late for her to save the business.

8—“I want to be a different self from the one I was ten years ago, five years, last week, two seconds ago.”

What makes a self, asks Lamorna Ash in her column this week. How should we imagine the self? As something fixed, or something far more discontinuous?

This notion of an ever-reforming self is not a waiver for behaving inconsistently. It does not release us from accountability for things our past selves have done. “A strongly impermanentist person may have a rocklike sense of self, and be very consistent over time,” Strawson notes. What it might do is free up the way we perceive ourselves and those around us, making greater space for one another’s complexities and our capacity to change. It might make the future feel less absolutely set.

9—“This one-size-fits-all policy promised to stave off immiseration with a simplified social safety net.”

Once again, the zombie idea that is universal basic income (UBI) is “doing the rounds again”, as Paul Johnson of the Institute for Fiscal Studies wrote in his recent book. Oliver Eagleton has written for us on the idea’s unexpected foundations in the work of Milton Friedman.

To begin with, the philosophy of UBI was underpinned by a sense that policymakers couldn’t know what people truly wanted or needed, so it was best to let the people themselves decide. Yet this humility is absent from the welfare programmes designed by contemporary free-marketers, who have implemented ever-more restrictive forms of means-testing along with rigorous schemes to monitor and control the behaviour of recipients: forcing them to apply for a fixed quota of jobs each week, attend regular appointments and training courses, meet an increasing burden of proof to demonstrate their eligibility, and so on. Under the Cameron-Osborne government in the UK these conditions were drastically multiplied.

Best of the Rest

Times: Labour prepared to build on green belt. Starmer secures the Yimby vote.

FT: Big trouble in little Teesside. Another part of the 2019 realignment bites the dust.

Telegraph: Carrie Johnson announces that she is pregnant (again). If only the British economy was as productive as Boris Johnson.

Chimamanda Adichie: How I became black in America.

Emma Green: A club for the cancelled.

Matthew Parris: The next Tory leader of the opposition.

Henry Kissinger: How to avoid the Third World War. It doesn’t involve illegally bombing Cambodia.

Janan Ganesh: You’re allowed to blame “the people”.

Damian Green’s sewage paddling. Britain, you will swim in the sewage and be grateful for it.

Elsewhere on the NS

Lewis Goodall was also at NatCon this week, and picked up on a remarkable admission by Jacob Rees-Mogg. The modern right, Lewis argues, is failing its history: it now foolishly sees extensions of the franchise as a threat, rather than an opportunity.

How did British conservatism lose the plot? Turn to this Andrew Gamble essay for answers.

What do Elon Musk and the YouTuber MrBeast have in common? They are both bringing back the 19th-century company town, writes Sarah Manavis.

The Smiths were a special band. Their bassist Andy Rourke died yesterday. It wasn’t just Morrissey’s lyrics that inspired Mat Osman of Suede, but the music that allowed them to soar. “There’s an exuberance, an embarrassment of riches, a sheer head-rush, that perhaps can only be made by a young band learning exactly how good they could be.”

“Governments have understood what is needed to make the system work for at least 25 years, but they have been prevented from doing so by wealthy landowners, the industry that serves them and the political failure to change a system that overcharges leaseholders by hundreds of millions per year.”

“Want to give your op-ed a bit of moral welly? Reach for George.”

Rachel Cooke reviews yet another true crime drama about men killing women that is “written by a man, and directed by one, [which] tells us nothing whatsoever that we do not know already”.

Liz Truss in Taipei had little to do with Taiwan, writes Katie Stallard: “She is settling domestic political scores and trying to rebrand herself from failed politician to valiant freedom fighter.”

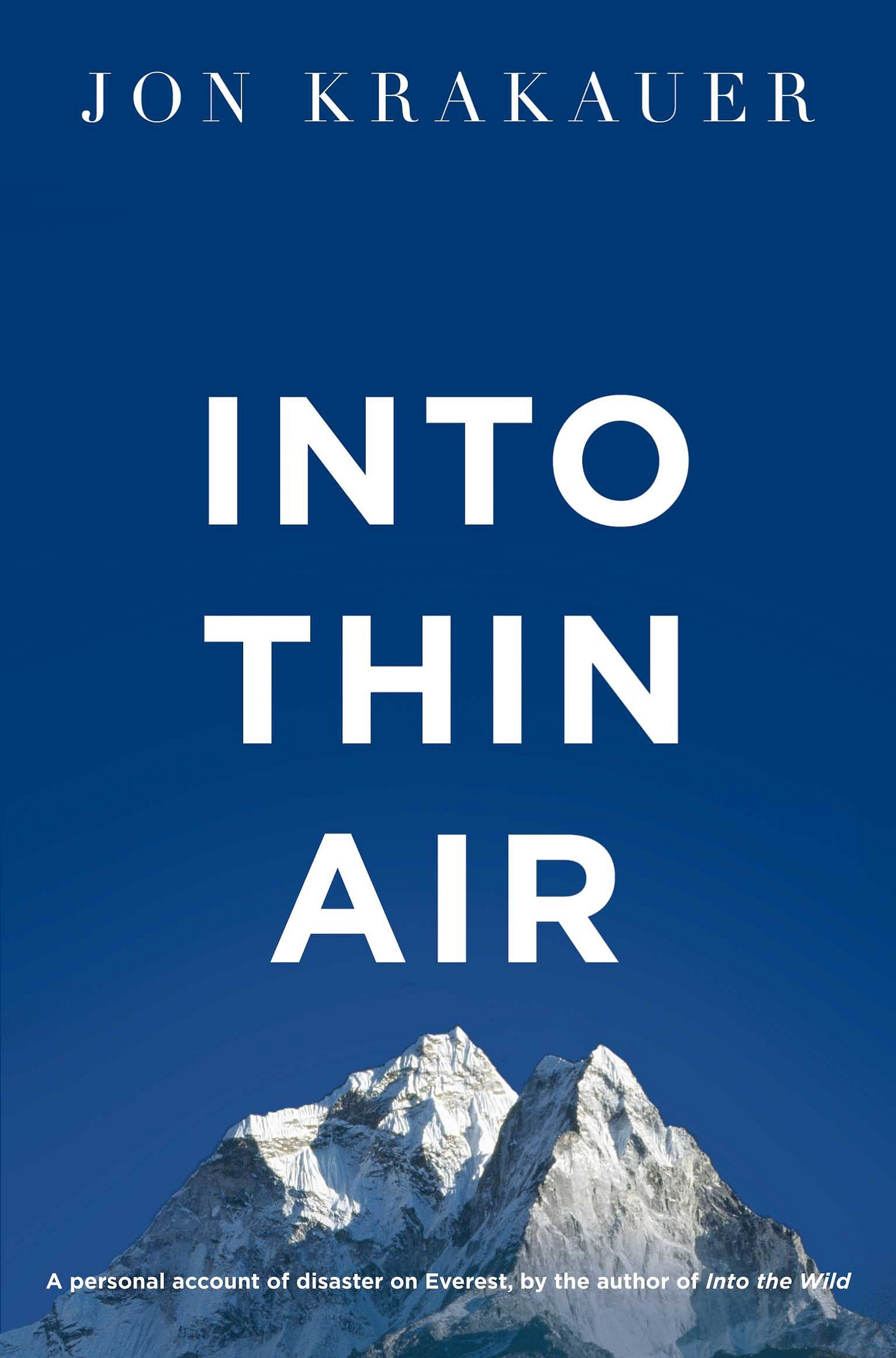

How to get into: Mountaineering

Each week we ask someone to recommend three books as a way into a subject. This week we turned to Pippa Bailey, our managing editor, production, who loves to read of others scaling heights she does not wish to ascend herself.

Touching the Void by Joe Simpson (1998): You’ll likely have seen the Bafta-winning film based on this book, as I did, far too young. While descending from the summit of Siula Grande in the Peruvian Andes, Joe Simpson broke his right leg. When evacuation attempts failed, his climbing partner cut the rope tying the two of them together – and left him for dead.

Into Thin Air by Jon Krakauer (2011): In 1996 three expeditions were caught in a storm while descending from the summit of Everest. By the end of the day, eight climbers were dead. Krakauer, an experienced climber and journalist, was sent by Outside magazine to join the US expedition, led by Rob Hall. His account of what unfolded prompted another survivor, Anatoli Boukreev, to write his own account in rebuttal.

Into the Silence by Wade Davis (2012): This Baillie Gifford Prize-winning book tells the stories of the three British expeditions that set out for Everest between 1921 and 1924, including legendary names such as George Mallory and Andrew Irvine. But it is also about how, postwar, the pursuit of Everest became a symbol of hope in the national imagination; and about how, for the men who fought and then went on to climb mountains, the Great War changed the meaning of risk.

This week’s replies

Marcus Walker: I keep coming back to this interview and keep thinking how it betrays one of the huge unresolved questions in British politics: to what extent can a person whose whole philosophy runs against that of a gov’t oversee the implementation of their objectives? (For counter-pieces to Simon McDonald’s interview with us, see The Times and Engelsberg Ideas.)

Lorena O’Neil: Absolutely heartbreaking reporting by @bhatiap on what’s happening in Haiti. (If you missed Pooja’s piece on Haiti last week, Kate Mossman has read it for our audio long read today.)

Tim Bale: Absolutely loved this piece by @freddiejh8. (On “Britain’s resentful right”.)

And with that…

One of the fun things about this week’s National Conservatism conference was watching head-in-a-history-book commentators try to explain how this ideology, which is very American and impossible to imagine without Donald Trump, actually had deep roots in British political thought. The same move was made throughout the three-day conference, with peculiar, needy invocations of Benjamin Disraeli’s “One Nation Conservatism” made by numerous speakers.

What is One Nation Conservatism? It is cynicism. It is British Toryism, which is less a settled creed than a genius/charlatan capacity for reinvention. In short, promise the lower orders slightly better living standards and you won’t have to reform Britain in any significant way. The last Conservative prime minister to take this tradition for a spin was Boris Johnson, which tells its own story. On Wednesday, NatConference boiled down to its dregs with a speech by Lee Anderson. It was a bathetic, weirdly poignant climax.

Anderson is what One Nation Toryism creates. The MP, as Ferdinand Mount once wrote of Norman Tebbit, is “gloriously common” – the Conservatives’ inflatable working-class man. They use him as a mouthpiece for things that less gauche Tories believe, but would never state publicly. For a brief moment after 2019, he spoke for the Red Wall, he was the Red Wall. How did that work out? How is levelling up going? How united is this one nation three and a half years after that election?

On Wednesday afternoon, Anderson couldn’t even be bothered to work through his usual talking points. “I was from the roughest street in Ashfield, piss poor,” said Anderson quietly to the near-empty hall. “And now I’m deputy chair of the Conservative Party… not sure for how long.” The Tories will reinvent themselves again. Just don’t expect their next poster boy to look like Anderson.

Thank you for reading. Don’t miss out – subscribe to the New Statesman and stay up to date with everything you need: from news and analysis to comment and criticism.

Whether you’re looking for a sharp blog or a finely written feature, the New Statesman has you covered. Have a good week, and catch you next Saturday.

Thanks to our colleague Barney Horner on this week’s edition.