The Saturday Read: Who will depend on whom?

Inside: AI, Waterstones Dad, Ukraine, Sontag, austerity, presidents, and three writers.

Good morning, and welcome to the Saturday Read, the New Statesman’s weekly guide to the best writing on ideas, politics, books and culture. This is Harry, along with Will.

NB: If this email doesn’t load for you in full, you can view it online (or in app) by clicking on the button you see when your email cuts off. The email hasn’t ended until you reach Will’s sign-off.

In the early hours of this morning, Yevgeny Prigozhin’s Wagner Group “crossed from occupied into Russia in at least two locations”, according to the Ministry of Defence. The Wagner Group has occupied “key security sites” in Ukraine and is now “almost certainly aiming to get to Moscow”. Putin has accused Prigozhin of treason and likened the uprising to the 1917 Russian revolution, saying that “the fate of our people is being decided”.

If the pieces below intrigue, perhaps you’d like to try a trial subscription to the NS. Read three free articles after registering on our site. A digital subscription is just 95p a week. If you are already a subscriber, thank you for reading us. Let’s get to it.

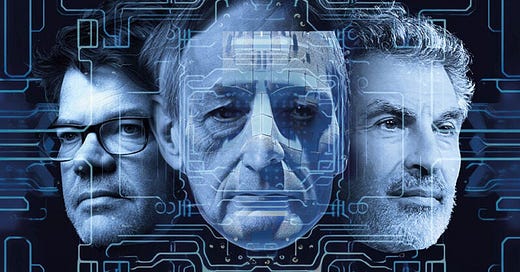

1—“I don’t think there is anything special about people, other than to other people.”

For this week’s cover, I’ve sought to bring alive the fervent debate around AI – existential threat or humanity’s salvation? – through the story of Geoff Hinton, the AI pioneer who recently resigned from Google to warn the world of what’s ahead: “I decided to shout fire. I don’t know what to do about it or which way to run.”

I had always found the AI debate abstract, irrelevant even, until I met him. But Hinton is a fascinating figure. (You can listen to the piece here if you like.)

In the days after his talk at Cambridge, I met Hinton at his home near Hampstead, north London. “Emotionally, I don’t believe what I’m saying [about AI],” he told me. “I just believe it intellectually.” What is stopping him from believing it? “Well, it’s too awful.” What is? “Them taking over. It’s not going to be pretty. Did you ever see a big change of power like that, that was pretty?” But couldn’t we turn off a machine that threatened us? “No, you can’t. You will be completely dependent on it by then.”

2—“The proliferation of Dad non-fiction corresponds to the general evacuation of ideas from the public sphere.”

Who is Waterstones Dad? That’s not a question that had ever been asked before this week, when it trended for days. The answer, as our ideas editor, Gavin Jacobson, explains in this mass drive-by polemic, is that he is everything wrong with British non-fiction publishing.

Exasperated at the political state of the country, for which he mostly blames Brexit, Boris Johnson and Corbyn, he yearns for that prelapsarian time before 2016 when Britain stood as an archetype of steady bourgeois moderation. But he can no longer stomach the miasmic torpor of the edifice and its revolving cast of morticians in parliament. Ian Dunt, the poor man’s poor man’s Orwell, provided some catharsis with his post-Brexit vade mecum What the Hell Happens Now?. The mounting volumes of centrist freakout, most of which are extended Twitter threads with ISBN numbers, both confirm and feed his minatory finger-wagging.

These books also keep Waterstones Dad reassuringly in the dark, as they seldom challenge (or even mention) the material foundations – capitalism – upon which his comfort rests: rising house prices, stock market booms, asset bubbles, bailouts, quantitative easing, steady work in the core and exploited labour on the peripheries of society, and the plunder of the world’s resources.

They locate the pathologies of the nation’s discontents in the juvenile quality of the ministerial class, the sclerotic condition of the political parties or in the political system itself – in the problems of populist energy and deadlocked parliaments. There’s no need to contemplate radical alternatives to the rentier economy, to do more than soften the status quo through a bit more tax and a little bit more state, to aspire for a national culture beyond stinginess sweetened by nostalgia, when all we must do is sit down (in a podcast studio, perhaps) and just learn How to Disagree agreeably.

3—“The goal would be to stop Ukraine’s offensive before it starts and to freeze the line of contact.”

Bruno Maçães, our foreign affairs correspondent, has been in the Ribalsky compound of Ukraine’s military intelligence services in Kyiv, talking to Kyrylo Budanov, Ukraine’s primary intelligence official. Budanov fears that Russia is readying to blow up the Zaporizhzhia nuclear power plant to halt Ukraine’s nascent counter-offensive – a fear Zelensky himself has voiced.

I asked Ukraine’s spymaster if the decision to blow up the power plant has been taken. He is confident the plan is fully “drafted and approved”. The only element missing is the order to go ahead. “Then it can happen in a matter of minutes.”

Whether the order will come depends on how Russia sees the potential benefits from a nuclear disaster in southern Ukraine. Budanov told me there are two possibilities. The first would be to blow up the power plant if its forces get ousted from the left bank of the Dnieper river. Russia would then create a zone of destruction and exclusion as a way to prevent Ukraine from advancing. The strategy may also serve as a threat not to attack Russian positions.

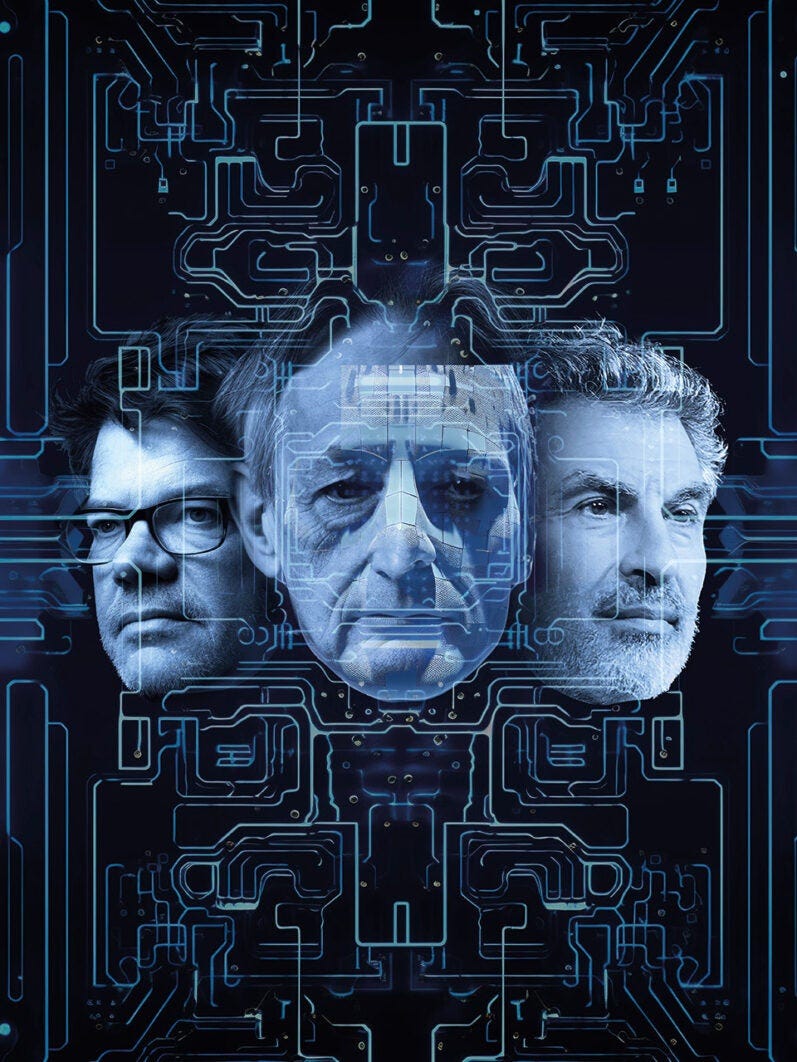

4—“Sontag’s determined rejection of complacency leads her to unfeeling, unsisterly arguments.”

It is always fascinating when Anna tackles one of the Great Literary Figures. This week: Susan Sontag.

Arranged chronologically, these essays from 1972 to 1975 reveal Sontag’s relationship to feminism as initially reluctant, subsequently militant, and ultimately frustrated. It was a movement that never quite seemed to her radical enough, intellectual enough, serious enough. In “The Third World of Women”, a response to a questionnaire sent by the short-lived leftist magazine Libre, Sontag sets out her views on the fight for women’s liberation. She writes that as a teenager “it never even occurred to me that I might be prevented from doing things in ‘the world’ because I was born female… I was curiously innocent of the very existence of a barrier.”

5—“Osborne, after a cleansing dip in the worlds of Fleet Street and venture capital, has now been fully laundered into cosy pundit status.”

Anoosh was at the Covid inquiry this week, where austerity was in the dock. David Cameron and George Osborne, effectively for the first time, faced questions over the impact of their flagship policy on the UK’s pandemic preparation.

“They’re not going to accept responsibility for anything,” one bereaved daughter told Anoosh afterwards. “I didn’t know about austerity when it was happening, I wasn’t political before this. But now I know that their failures go way back.”

Cameron, who appeared before the inquiry on the morning of 19 June, still performed the anxious-aggressive hand gesture that he perfected as prime minister – spreading his fingers and pressing down firmly on an invisible beach ball. Twiddling his glasses and sitting on the edge of his chair, he listened to the charge that his cuts hindered the UK’s “preparedness and resilience for a pandemic”, the theme of the first phase of the inquiry.

Osborne, hands clasped and face egg-white, was even less contrite than Cameron. He rejected the idea that his Treasury could have prepared for lockdown (its only nod towards pandemic planning was funding a call centre and buying some antibiotics in 2012). Even if he’d been advised to prime the UK for staying at home, he questioned whether “we would have thought that was a plausible plan” at all.

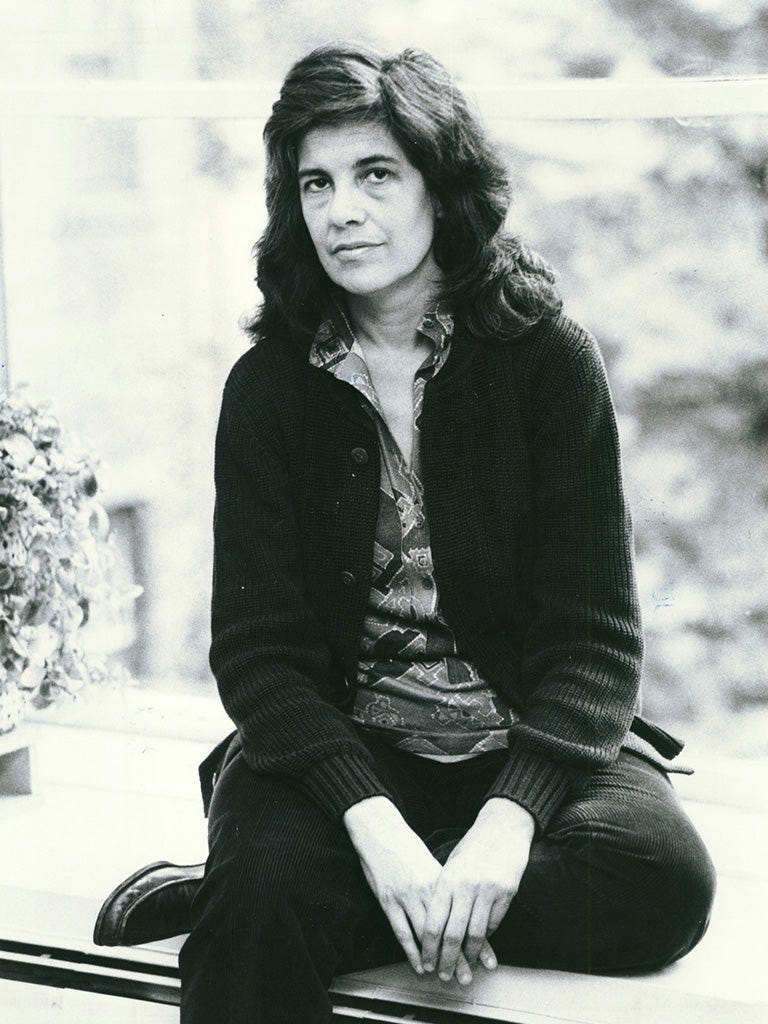

6—“Presidents and prime ministers, like everyone else, often go through life intent on pleasing or defying a difficult parent.”

Adam Hochschild, the author of King Leopold’s Ghost (1998) among much else, has written a fine piece on Woodrow Wilson, reflecting on a new book, and the role of Wilson’s severe father in shaping the American president’s ill-fated premiership.

In Wilson’s case, Weil asserts, the president’s psychological difficulties led to an immense tragedy. “If the United States had ratified [the] Treaty of Versailles,” he claims, “history would likely have taken a different course.” This seems wildly improbable. A League of Nations including the US would likely have been little more successful at preventing wars than was the League without – or than the United Nations has been since 1945.

It is impossible to imagine the US rushing troops to prevent Mussolini from taking over Ethiopia, or Hitler Austria and the Sudetenland. If the US had signed the treaty, Weil writes, “Soon enough German reparations would have been lowered” – ignoring that, in effect, they were lowered in the 1920s, something that still failed to erase the great bitterness and resentment that the Nazis would make such fateful use of.

7—“We have lost one of the greatest explorers of what lies beyond the shaky constructs on which we rely to guide us through life.”

When Cormac McCarthy died on 13 June in Santa Fe, New Mexico, there was only one person I wanted to read on his life and work: John Gray.

In its surrender to mystery, McCarthy’s sensibility was religious. Unlike the religions with which we are familiar, he does not offer any glimpse of a final harmony. Even Buddhism, by the standards of Western monotheism an atheist faith, holds out the prospect of nirvana, release from suffering. McCarthy comes closer to the faiths of ancient Mexico, on which DH Lawrence drew in The Plumed Serpent (1926).

There is no evidence that he read the prolific English writer, but there are parallels between the religion implicit in McCarthy’s novels and that sketched in Lawrence’s writings on Mexico. In both, human beings are not accidentally embodied minds but mortal creatures of flesh and blood, whose fates are as random and inescapable as those of birds and toads. All living things find themselves in a state of war.

8—“Kolakowski was a man haunted by the absolute.”

Madoc Cairns goes deep into the life of Leszek Kołakowski, and finds in the Marxist-turned-Catholic philosopher and historian a thinker whose work explains our age of tragedy.

John Gray read Madoc’s piece this week. He writes in: “I got to know Kołakowski well in the Eighties and Nineties, when we used to talk over a few glasses in his room at All Souls and sometimes in Italy. He was always a tragic thinker, I think, even when I first knew him. He was convinced that without some transcendental presence the human world is a place of metaphysical horror, but as far as I could tell never had any belief in such a presence himself, despite earnestly wishing that he did. Cairns’s excellent piece is the only one I’ve read that captures the tragic aspect of his thought.”

Leszek refused to answer. He never would. Every one of his transformations was like this: double-edged, paradoxical, enigmatic. He left atheism, but wouldn’t confess belief; attacked Marxism on Marxist grounds; when he was asked what political beliefs he held his answer was: all of them. I’m a liberal-conservative-socialist, he declared in a 1978 essay, loyal to absolute values from each tradition: but that loyalty was never absolute. For Kolakowski, nothing was ever quite certain. In philosophy, as in life, there were no guarantees.

9—“For better or worse, McEwan has been the dominant British fiction writer of his era.”

Ian McEwan has turned 75. There has been, says Leo Robson, no obvious precedent for the novelist’s successes, longevity, consistency or range.

In the final pages of Atonement, Briony, now a famous novelist, is marking her 77th birthday, looking back, winding down. She notes that she had always liked to “make a tidy finish”, and so has McEwan, with his kick-yourself twists and hyper-logical resolutions, those dinky clock-like mechanisms that risk rendering a vice of his virtuosity. Lessons had elements of the summa or swansong, but he has revealed he is currently drafting a successor.

Will’s Best of the Rest

Atlantic: How deterrence policies create border chaos.

Telegraph: Recession “inevitable” in Britain.

Chronicle: A left-wing case for conspiracy theory.

Amia Srinivasan: Free speech on campus.

Graham Allison: China’s dominance of solar threatens the West.

Frank Luntz: The most polarising political value in the UK is equality.

Helen Lewis: The feminists who think women are built differently.

Elsewhere on the NS

Political culture is the origin of emotional connection, writes Andrew in his column this week – but what is Labour’s culture today?

The era of cheap money is over. What now? Our Leader this week offers answers.

Can Labour afford to be radical? Will Dunn has spoken to familiar leading names in the fiscal world in a bid to find out. (They would need to raise taxes, but they keep ruling out major options for new rises, such as new taxes on wealth.)

Katie reports on Anthony Blinken’s visit to China. The US-China relationship, as one official tells her, increasing resembles “an airplane steadily losing altitude”.

There is no global conspiracy to confine people to “15-minute cities”. But, Michael Lind argues, that doesn’t mean that they are a good idea, or will ever be popular with the working classes.

The internet hasn’t killed newspapers, writes Stephen Glover. If anything, the race to buy the Telegraph Media Group shows just how financially alluring to buyers they still are.

Wes Anderson has made his most affected film yet, says David Sexton.

When Elizabeth Gilbert pulled her new novel from booksellers – after no less an authority than 500 Goodreads accounts told her it was a Bad Thing to write about Russia while the war in Ukraine grinds on – she was not giving up on her own work. She was, explains Charlotte Stroud, giving up on literature itself.

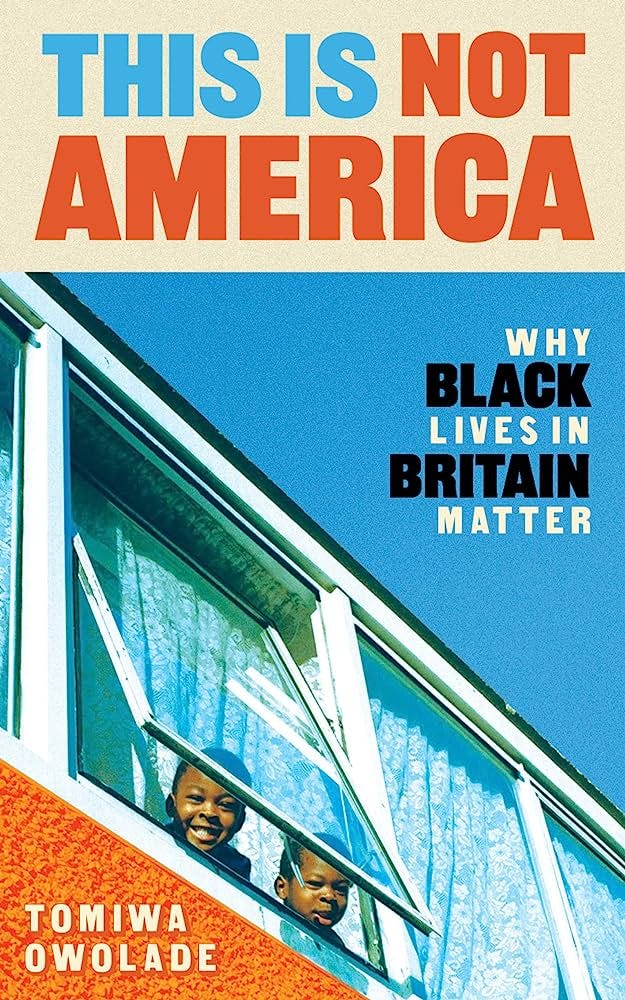

Tomiwa Owolade, who published his debut book, This Is Not America, this week, has written for us on the ambiguous legacies of Windrush. Black Britain, he argues, is not what it used to be.

Perhaps you might like our daily political email. One in five Saturday Readers subscribe.

A primer on: Grace Paley

This week we asked Melissa Denes, our features editor, to reflect on the one-year anniversary of the Dobbs decision, the US Supreme Court ruling which led to the fall of Roe vs Wade. That sent her back to a favourite American writer, Grace Paley. Melissa writes:

Paley would have been appalled, only that’s not the word she would have used. A fierce, funny, optimist-activist from the Bronx, the daughter of Ukrainian Jews (Philip Roth praised her “deep feelings, wild imagination, and style of toughness and bumpiness”), she would have been mad. Fourteen US states now have a full abortion ban, while five more impose severe restrictions. How did we get back here?

In her 1991 essay “The Illegal Days”, Paley wrote about the abortion she had in the 1940s: “The guy was very clean, and he was very good, and he was arrested within the next year. He went to jail.” She was clear-sighted and warned against a return to an era when “women died all the time”, organising one of the first abortion speak-outs in New York in the 1960s.

I interviewed her in Vermont when she was 81 – still writing, teaching and campaigning, a note reading “For the night cometh when no man can work” pinned over her desk – and I wish she were still here. But in the meantime, for a reminder of how essential, exhausting and riotous the feminist fight can be, read these.

Just as I Thought (1998): Essays, articles and lectures from 30 years in the civil rights, anti-war and feminist movements by the self-described “combative pacifist and cooperative anarchist”.

The Collected Stories (1994): Childhood, motherhood, friendship, politics, the immigrant experience, relayed in exuberant and experimental form. (Paley tried a novel and found it too “pedestrian”.)

Begin Again: Collected Poems (2000): Paley, distilled.

And with that…

Question Time is dead, isn’t it? Pre-pandemic, the topical debate panel show drew around four million viewers. That audience has reportedly halved in the years since. Take a longer view, back to 1979 when Question Time first aired, and you can see that the conditions that made it seem like a good idea – political panel show as democratic umbilical cord linking the people to various establishment talking heads – no longer exist. Other, crueller, more direct conduits for people to express their views to the powerful have been invented. They are not moderated by anybody as polite as Fiona Bruce. They are not moderated by anybody at all.

On Thursday, Question Time did a stunt edition in the melancholic end-o’-the pier Essex town of Clacton-on-Sea. All of the audience had voted for Brexit, and most of them still backed the decision to leave the European Union. My mother is from Essex, and I spent time in Clacton when I was a child and a teenager. The town never symbolised anything to me other than the decrepit Englishness – smell of frying donuts, blue tattoos turned green with age on leathery skin – romanticised by Morrissey in Everyday Is Like Sunday.

Ever since Matthew Parris wrote a scathing column about the place in 2014 (“Tories should turn their backs on Clacton”), and ever since the post-Brexit media zeroed in on England’s apparently deprived coastal communities as a way of explaining why Leave won, Clacton has not been Clacton. Its hot dog stalls and fading amusement arcades have come to stand for a peculiar, half-articulate form of nostalgic English rage.

Bruce addressed Clatonites with the cheerful chumminess of a colonial medical officer encountering their first native in Sudan around 1878. Did she pack her skull-measuring equipment, I wondered, as she asked: “What do they think of it all [Brexit] now?” Mostly, they think Brexit is good. Being patronised by the BBC is unlikely to change their minds. I imagine that before they do, Question Time will no longer exist.

Harry adds, on the cricket – so much for scintillating. England inexplicably shied away from attacking Australia late and lost the first Test. The second test, at Lord’s, starts Wednesday.

Thank you for reading. Don’t miss out – subscribe to the New Statesman and stay up to date with everything you need: from news and analysis to comment and criticism.

Whether you’re looking for a sharp blog or a finely written feature, the New Statesman has you covered. Have a good week, and catch you next Saturday.

Thanks to our colleague Chris Bourn.