The Saturday Read: Zeitgeist

Inside: 100 years of Gatsby, the dollar, Royal Mail, Steve Rosenberg in Moscow, a Hockney retrospective, the dark side of the Moomins, and Taylor Swift’s bank account.

Good morning. Welcome to the Saturday Read, the best of the New Statesman, in print and online this week. This is Finn with Nicholas and George.

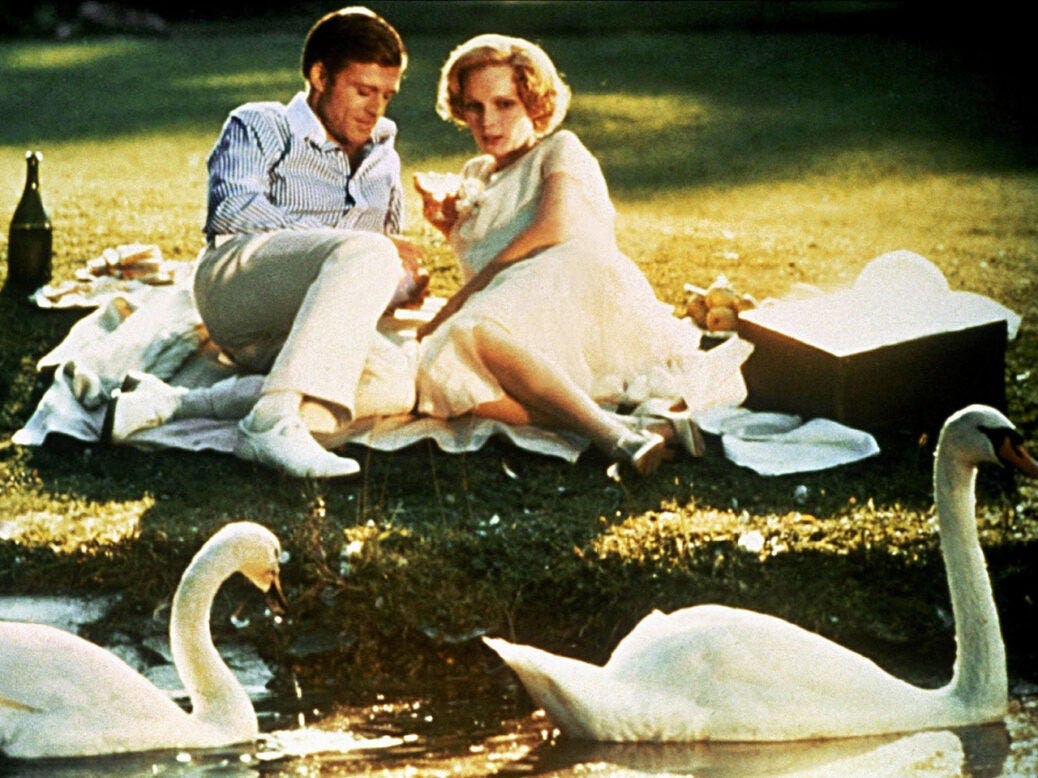

So the tariffs beat on ceaselessly into the news… But at the New Statesman we have been preoccupied with another event. Happy birthday to F Scott Fitzgerald’s The Great Gatsby – 100 years on Thursday! It should receive a missive from the King any day now.

It is hard to judge how contemporary fiction will age. (Will any novel published today receive the reverential Gatsby treatment in 2125?) There are two mistakes people make when it comes to assessing the cultural longevity of a new novel: over-indexing the importance of zeitgeisty themes, and making the fatally common mistake that the politics of the moment will be interesting in the future. Sometimes fiction that feels timeless ends up ageing like milk.

So, what will end up canonical and what will get consigned to the huge scrap heap of literary history? Some suggestions for the great 21st century novels from the office: Alan Hollinghurst’s The Line of Beauty, Zadie Smith’s White Teeth, Ian McEwan’s Atonement. Write in (by replying to this email) with your contenders, and we can check in in 100 years time to see who was right.

Down below we have a dispatch from Birmingham – a city in crisis, a review of David Hockney’s Paris retrospective, and a question mark over the future of the dollar. As ever, thanks for reading and have a great weekend.

1—“Grossly overvalued”

Amid the sudden jerking motions of Trump’s tariff war, the market for dollar assets sounded the alarm. Bruno Maçães suggests it’s both a blessing and a curse that the US holds the global reserve currency. Might the source of American hegemony also be its ultimate undoing? FMcR

Stephen Miran, who heads Trump’s Chair of the Council of Economic Advisers, explained in a much-discussed paper from last year that the dialectic tends to get worse with time, until the moment when the status quo becomes radically unsustainable. As the United States shrinks relative to the global economy, it must export a larger share of financial assets to sustain global trade and investment, thereby necessitating larger deficits and imbalances. In the process, the consequences for its own real economy, manufacturing and exports also become more difficult to bear. Reading his paper one image came to mind: if Russia is a gas station with nukes, America risks becoming Wall Street with nukes.

2—“Britain’s forgotten city”

We dispatched policy correspondent Harry Clarke-Ezzidio to Birmingham this week to investigate the growing piles of trash that line the streets. A five-week long bin strike; a bankrupt council: Birmingham is in disarray. But this is a national crisis playing out on a local level. FMcR

At a four-way mini-roundabout in Alum Rock, all roads lead to mounds of rubbish: outside a fried chicken shop, topped by a dripping container of oil; past the local car wash; outside a corner shop; and in a smaller cluster going towards residential properties. How long had it been there? “Dunno,” a man, looking in his early twenties, told me swiftly after adding another black bag to the pile outside the chicken shop.

3—“Money, brutality”

I never miss Lee Siegel on America, so I would certainly never miss him on a great American novel. Lee interrogates Gatsby’s America, “which is also our own”. GM

Gatsby is one long de-idealisation, though curiously it never loses its own stubborn romanticism. In that, the book has the alcoholic character of its author. “I’m the first man who ever made a stable out of a garage,” the polo-playing Tom boasts to Gatsby, and you think of Gatsby’s literary forebear, Flaubert’s doomed romantic Emma Bovary, who is seduced with high sentiments amid the odours of an agricultural fair. The promise of American capitalism, once embodied by Henry Ford’s affordable automobiles, has been reduced to the “dust-covered wreck of a Ford” in Wilson’s garage. The wraithlike Wilson is all that is left of Woodrow Wilson’s progressive ideals.

4—“Decline was not inevitable”

Not even Thatcher was willing to privatise the Royal Mail. But from the end of this month it will be controlled by a Czech billionaire known for profiting from dying industry. This is the natural end point to decades-old government strategy, Jason laments. GM

As the historian David Edgerton has written, the United Kingdom in the postwar period once pursued a distinctive form of national capitalism. “This national industry supplied the British people with nearly all their common infrastructure – railways, roads and energy – as well as their cars, TVs, aeroplanes and clothes.” Today, raw sewage is poured into rivers by water companies owned by overseas firms. Letters are sent but are delayed or never arrive (I have had no post for nearly two weeks). Our disaggregated rail network is the most expensive for passengers in Europe. Decades of careless misrule have weakened Britain’s national infrastructure and left us wide open to threats from hostile powers as the world darkens. The slow death of the Royal Mail is a parable of the modern British state.

5—“Justice might catch up”

During Rodrigo Duterte’s first six months in power over the Philippines, an average of 34 people were killed every day. Back in 2016, he called the International Criminal Court “bullshit”. Last month, he was arrested in Manila to be transferred to the Hague. Katie Stallard explains how the strongman was caught. GM

Yet when Duterte’s plane landed at Manila’s main airport, the arrivals hall was swarming with police. An officer boarded the plane to inform Duterte that he would be arrested. “You will just have to kill me,” he responded. “I won’t allow it if you’re taking the ICC’s side.” When it came down to it, however, he did not offer much resistance, allowing himself to be escorted to the presidential lounge at a nearby air base, where he reportedly dined on barbecued meat and drank Coke. Then an officer read him his rights, advising him that he was being arrested on a warrant from the ICC for crimes against humanity, and that he had the right to remain silent and to legal counsel of his choice. It was more than any of his alleged victims had been offered. Duterte, who appeared frail and often walks with a stick, was then helped up the steps on to a waiting private jet to be transported to the Netherlands.

To enjoy our latest analysis of politics, news and events, in addition to world-class literary and cultural reviews, click here to subscribe to the New Statesman. You'll enjoy all of the New Statesman's online content, ad-free podcasts and invitations to NS events.

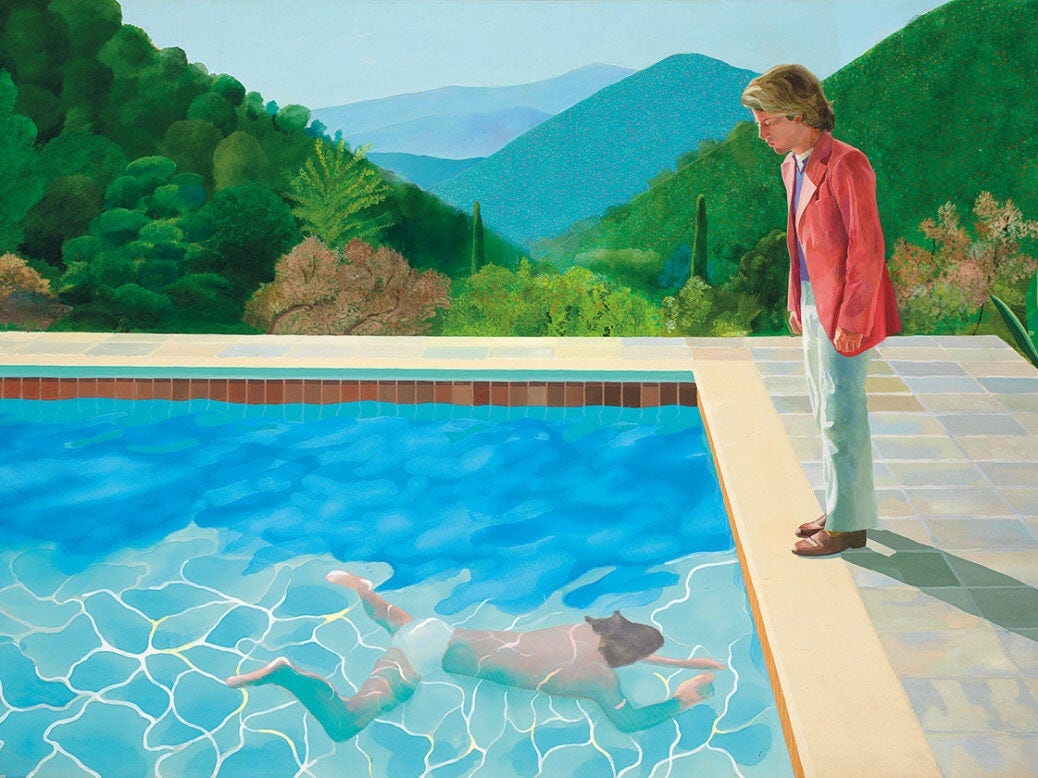

6—“This underwater world”

Steve Rosenberg is the BBC’s Moscow correspondent and one of the few Western journalists left in Russia. He explains to Kate Mossman why reporting from there is like being a deep sea diver: “You need to come up for air every three months.” FMcR

Many teenagers develop an obsession with the USSR, their latent revolutionary instincts inflamed by cool photos of Trotsky in his little round glasses. But Rosenberg was a perestroika boy from the start: he watched a BBC Russian-language course featuring a poignant national song called “Goodbye Summer”. When he accompanied Gorbachev on piano in 2013 after an interview (Gorby sang “Moscow Nights” and “Misty Morning”), it told him more about the former president than any of the pair’s five press encounters: “He was a typical politician, but when he sang it showed his humanity.” It is hard to imagine Putin doing a sing-song.

7—“Drawing and drawing”

One of the great draughtsmen of the 20th century has turned to the iPad in recent years to render his work. It’s a shame. Michael Prodger reviews an authorised David Hockney retrospective in Paris and finds a brave artist sidetracked from his greatest strengths. FMcR

Their inclusion in such profusion suggests that Hockney himself regards them as among his best work: a dispassionate outsider might disagree. This disconnect is even more obvious in his pictures of people rather than nature. The younger Hockney was a portraitist of extraordinary subtlety and finesse but the display here shows a poignant tailing off in his skills. The line that was once so precise has become, unsurprisingly given his frail health, wavering; the ability to capture a likeness and a look has waned. This diminution can be dated to 2018/19 when his control demonstrably starts to slip. For example, the presence of his portrait of Norman Rosenthal, made just last year, might be an elegant nod of thanks to his co-curator but it will do nothing for the reputation of either sitter or artist.

8—“There is no happy ending”

A dark shadow has fallen on Moominvalley... These mythical Finnish hippo-like creatures are not cuddly and child-friendly. Instead, their stories are ones of confusion, emptiness and apocalypse. 80 years on from its conception, Frances Wilson surveys the haunting Moominverse. FMcR

The Moomins, at this point in their gestation, were broad-backed with trunk-like noses, horn-like ears, and flattish stomachs. Their waistlines increased with fame, but their characteristics remained the same: anxious, romantic Moomintroll, dependable Moominmamma, and Moominpappa, the reckless, self-absorbed melancholic whose longing for adventure threatens to destroy them all… The Moomins and the Great Flood ends with the creation of Moominvalley, the kind of place that the psychotherapist Donald Winnicott – in whom Jansson had a strong interest – would call a “holding environment” where we can be determinedly ourselves. United in solipsism and contained by the love of Moominmamma, the Moomins and their eccentric friends live out their philosophies, compulsions, obsessions, paranoias, and various neuroses.

9—“Business secrets of Taylor Swift”

All artists are hucksters, however much we like them. But in reviewing a new study of Swift’s commercial ascendancy, Will Dunn embraces the craze – her appeal is a mystery balance sheets cannot measure. NH

This book is perhaps most interesting when Evers admits for a moment that he can’t really say what makes Swift historically successful, and simply admires the effect she has on his daughter, Maisie. He watches as she listens, “lost in thought and emotion, absorbing every lyric and every note” in Swift’s music on a car journey, he thrills at the “delight and wide-eyed marvel” on her face when he takes her to her first Swift concert… There is a truth in there about successful art: we know when it’s working, but we can’t say how.

10—“A literary golden age”

Acting editor Tom Gatti opens up our Spring Special with an editor’s note. He covers Rob Reiner’s Stand By Me, an Olivia Rodrigo concert, and most importantly, delivers this very NS anecdote about Martin Amis. FMcR

I joined the New Statesman just after its centenary in 2013, and have since met several alumni, including Julian Barnes’s former boss Martin Amis. As Amis rolled a cigarette outside Grayson Perry’s studio – they were about to sit down for a conversation, for Perry’s guest edit of the magazine in 2014 – I asked him about his time running the books pages. I was half-expecting a droll deflection, but he replied earnestly: it was utterly absorbing, he said, so much so that it risked derailing his career as a novelist. Editing the New Statesman over the past few months, I have been reminded of these verdicts. It has been a privilege, and a lot of serious fun.

George’s Best of the Rest

Rafael Behr: Britain must turn from America

James Lanchester: Labour’s straitjacket

Patrick Maguire: Is it time for Starmer to be bold? No!

Janan Ganesh: The hopeless search for Trump’s cunning plan

Laura Sheahen: Van Gogh’s loneliness

James Wood: Not quite a normal novel

Me: Gatsby forever

Belgian football club apologises after holding minutes silence for player who is still alive

And with that…

Personally, I’m most excited for the James Bond car-chase ride – based, hopefully, on the Jaguar v Aston Martin dogfight in Die Another Day – though I’m sure the queues will be equally long for the Peruvian log flume in Paddington Land, or the participatory Helm’s Deep siege re-enactment over in Rohan World. I’m talking about the new Universal Studios theme park to be constructed in Bedfordshire, of course, which Keir Starmer announced this week. (Think those sprawling, ersatz Disneylands of Florida and California and transport it to the South Midlands.)

Sometimes, like a postmodern novel, life can be a little heavy-handed with its metaphors. And this one is actually stolen from a postmodern novel, Julian Barnes’s England, England, in which a billionaire builds a theme park of Englishness on the Isle of Wight. As for the real thing? Well, there are inoffensive heritage brands on offer: from Bond to Paddington. These institutions have become world-friendly commercial vehicles, wearing a kind of artificial Englishness with a kindly face.

One imagines a less marketable but perhaps more honest theme park of Englishness, one based on our more stubbornly insular cultural icons. A Carry On world where everyone is forced to speak in squeaky innuendo? An Alan Bennett experience where you can make your own miserable Talking Heads monologue? A Fawlty Towers resort where hoteliers beat their cheap foreign staff? AA Gill called us the “angry island”. It’s fortunate that it’s a face we never show the world.

The New Statesman is home to the finest writing on politics, culture and ideas. To stay up to date, subscribe using the link above.

— Finn, Nicholas and George.

- Gatsby still the best - followed by Crime and Punishmdnt - 2 never to be forgotten - surely not by me -

One of my favourite records is Blueberry Hill by Fats Domino. However, I have to admit that Vladimir Putin sang a fine version of it a few years ago.