The SR Feature: Jesse Armstrong's TV history

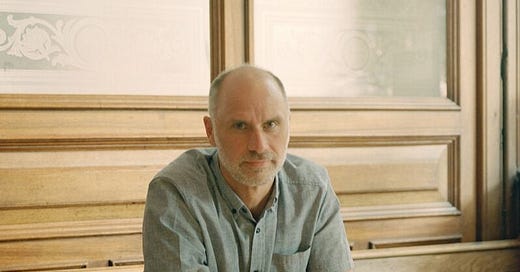

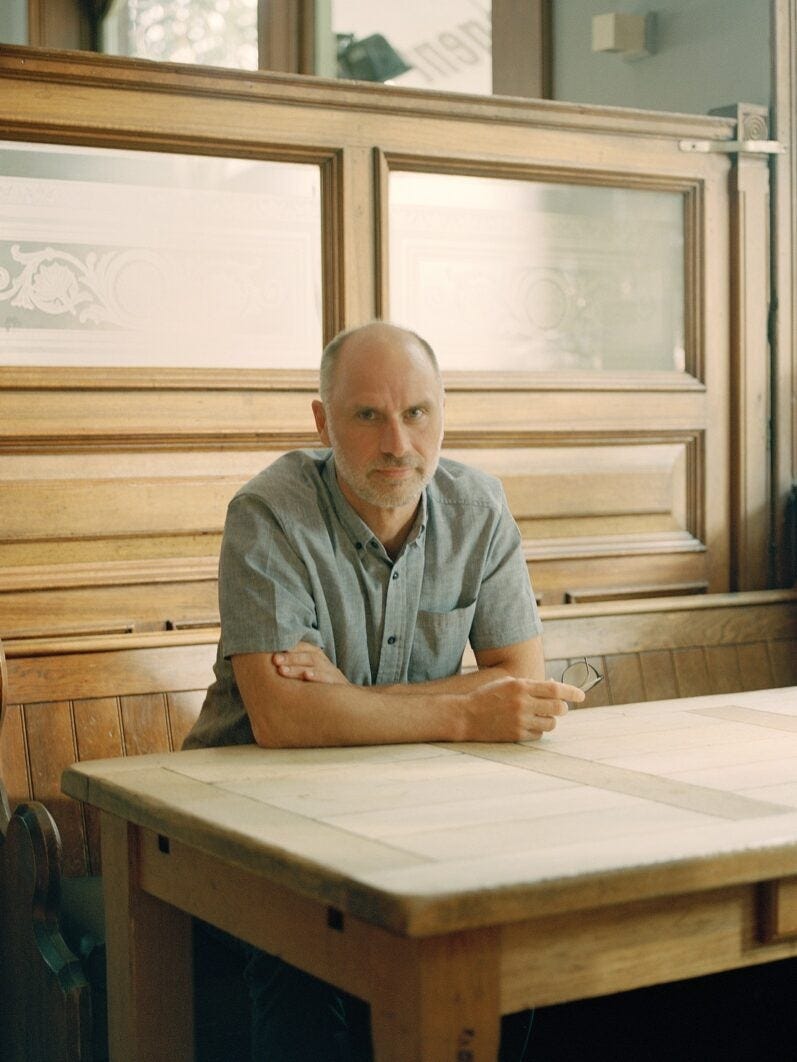

The "Succession" showrunner on the deification of Difficult Men.

Good morning. Welcome to the latest Saturday Read Feature. This is Harry, along with Will and Pippa.

We will have the main email with you on Saturday, featuring this week’s cover and a number of other striking pieces. But we wanted to send you this new essay by Jesse Armstrong, the architect of Succession, ahead of that.

He has written on Peter Biskind’s new, flawed history of TV. I gulped down Biskind’s Down and Dirty Pictures (2004), which glorified Robert Redford’s creation of the Sundance Film Festival – and Harvey Weinstein’s rise – to tell the story of independent film. Now Biskind, who recently filed for the NS, has written an account of TV’s “golden age” that Armstrong finds increasingly strained as his piece develops.

The review begins below. Click through to read it in full. (If you would just like to receive the main email you can adjust your settings by clicking through to Substack.)

Once, early in the process of making the pilot for Succession, one of the actors asked me: “Who is the showrunner on this thing?” The answer was that I hoped I was. But I knew why they asked the question. I didn’t entirely feel like the showrunner, nor was I perhaps acting like one yet. But that’s one of the odd things about the term – it is a position without definition or even formal recognition. It doesn’t say “showrunner” on the credits at the end of a TV show, nor is the position listed on the call sheets of each day’s shoot. As a role it’s a little like being a cult leader: you might not hold an official title, but everyone knows who you are, and you are the figure finally responsible for setting the tone of the endeavour – whether, overall, it will tend to promote human kindness and understanding, or lean more in the direction of taking folks into the jungle as you start to break out the Flavor Aid.

Peter Biskind has plenty of examples of every style of showrunning in his enjoyable new book about US television, Pandora’s Box: The Greed, Lust and Lies That Broke Television, from the Larry Sanders writing room where writer Janis Hirsch had “a flaccid penis… placed on my shoulder, you know, just for laughs” to Alan Ball’s Six Feet Under room, which Transparent creator Joey Soloway recalls as having been “like a therapy group”.

Biskind is the ex-executive editor of the film magazine Premiere and made his name with his book about the male auteurs of Seventies Hollywood, Easy Riders, Raging Bulls (1998). Now, he has made the same move much of the entertainment industry has in the past couple of decades – following the money from movies to TV.

Biskind’s argument is that “the river of sewage which was the nightly network line-up” was disrupted by the arrival of cable channels – first HBO, then Showtime, AMC and FX – which gave us a Golden Age of TV, allowing creators to produce the shows they wanted without restrictions on the content. But now the tech-led streamers such as Netflix, Amazon and Apple – once considered to be as innovative as the advent of cable – are on the verge of blanding out TV into a grey globalised goo, with content optimised by algorithms and bean-counters to please the same advertisers and broad audiences the networks used to chase.

Biskind takes a triple-pronged approach: he examines what he considers the key shows; takes in the merry-go-round of executives who green-lighted them; and breaks down some of the boardroom manoeuvres and takeovers of the corporations that employed those execs. As a result, you are never far from the next nugget of drama, conflict or bad behaviour. The book makes for a brisk read – and is a good primer on this latest Golden Age. However, in surveying the hundreds of TV shows mentioned – from Robert Altman’s satirical Tanner ’88 to this year’s The Idol – plus the personalities and power structures behind the productions, Biskind has set himself a big task. Maybe too big. With so much to cover, something has to give.

Have a good week, and catch you on Saturday for the main email. Thank you.