Welcome to the Saturday Read

Your new guide to the best writing – every weekend from the New Statesman.

Good morning. Forget the Saturday papers – welcome to the New Statesman’s Saturday Read, your new guide to the best writing on ideas, politics, books and culture each weekend. I’m Harry, your editor, and I’ll be writing this for you each week with my colleague, Will Lloyd.

The New Statesman, which celebrates 110 years in print next month, produces great writing every week: this newsletter was born out of us wanting to send you some of it. Every Saturday we will send you thoughts on, and snippets from, half a dozen of our leading articles, as well as links to other New Statesman pieces we think you might like. We will also direct you to intriguing articles from other outlets – you’ll find those in our “Best of the Rest” section.

We’ll always look to send you a mix of politics and culture, from a range of brilliant writers. Let us know what you think by replying to this email. If you are receiving this newsletter, you have either signed up to the Saturday Read or used to receive our Weekly Highlights email. This is our new offering. We hope you enjoy reading it every week.

If these pieces intrigue you, why not try a trial subscription to the NS? You can read up to three free articles after registering on the New Statesman website. A digital subscription is just 95p a week. We’d love to welcome you as a reader. Let’s get to it.

1—“Is Labour merely the beneficiary of Tory misrule, or has it earned the renewed respect of an electorate seeking protection and security in this age of disorder?”

Our editor, Jason Cowley, was in Berlin last week. He has written an editor’s note for this week’s magazine on the parallels between Olaf Scholz, the German chancellor, and Keir Starmer. The Labour leader also wrote exclusively in our pages this week, launching his plan for “mission-led government”.

Scholz, formerly finance minister and vice-chancellor in Angela Merkel’s Grand Coalition, resembles Starmer in some ways. He’s moderate, unglamorous, cautious, shrewd. Both men are lawyers – ideal preparation for a politician, as Max Weber put it in his celebrated lecture “Politics as a Vocation”. Scholz was once on the radical left – as Starmer was – before beginning his long journey to what the economist Paul Collier calls the hard centre.

In a speech on 23 February Starmer outlined his five “national missions” – which he has since elaborated on in an essay for the New Statesman. They were solid enough, but some of the language was desiccated. The SPD has a national mission: to lead Germany’s transition to a carbon-neutral future. The coalition’s finance minister, Christian Lindner, leader of the Free Democrats, calls renewables “freedom energy”.

But during the election campaign Scholz didn’t speak like this or in abstractions about green new deals and “the highest sustained growth in the G7”. He spoke about respect. After the SPD’s defeat in 2017, Scholz read widely – Michael Sandel on the failures of meritocracy, JD Vance’s Hillbilly Elegy, Didier Eribon’s Returning to Reims – and reflected on why social democrats had been losing support among working-class communities. What didn’t they understand? Why did so many voters feel abandoned or disrespected by those who purported to represent them?

2—“A simple question such as ‘what is the European Union?’ has no meaningful answer.”

Will visited Brussels to check in on a series of recently opened museums and exhibitions in Europe’s capital. In no other square mile on the continent are such strenuous efforts being made by the European Union to explain to the world what it actually is, and what it actually does. If these attempts fail, what does that tell us about the union’s future?

You’ll find Experience Europe in a promisingly grey office block on the corner of the Rue de la Loi and the Rue Froissart, opposite the star-shaped, prison-like Berlaymont building where the European Commission is housed. I visited on a Friday afternoon, as dozens of nicotine-stained bureaucrats, sagging after another day of institutional rivalries and email chains, headed down into the Schuman metro station. Experience Europe’s aim is to explain what the European Commission does. It takes up a single floor of the office building, which is filled with interactive screens, a miniature interactive cinema, and a bank of chairs attached to VR headsets.

Later, I met Ursula von der Leyen inside a cinema booth. “She’s not actually in there” said a helpful Experience Europe staffer. No, sadly, this was only a video Ursula. Again, the visitor pushes buttons to make a projection speak. Inside, a life-sized Von der Leyen appeared on a white background, studded with grinning, representative euro-citizens. She is simply another one of us. “Europe is the guiding star of my life,” said video Ursula. Each time another button is pushed, she gave another minute-long answer. At the end of each, you could all but see a message pass from her mind to her mouth: SMILE, read the message. Video Ursula seemed like a person who would look you in the eye while turning down your application for a loan.

3—“We’re duped into thinking it’s technology that’s made that possible, but of course it isn’t, it’s the labour that’s made it possible.”

Anoosh Chakelian captured the capital’s dependence on Deliveroo riders, the latest set of essential service workers that we have, three years after the pandemic, come to take for granted. She tells the story of what happened after one rider recently collapsed.

Somewhere between ghosts and butlers, Deliveroo riders are invisible to us until something goes wrong – our prawn crackers are missing, for example, or they cut us up in the cycle lane. Then they become customer service foot soldiers and targets for road rage. Between 2020 and 2021 the number of muggings, threats and sexual assaults of Deliveroo riders doubled.

Like post boxes and the yelp of sirens, they are now part of a city’s scenery, faceless turquoise blurs. Deliveroo, meanwhile, likes to portray its riders as mini entrepreneurs. They are self-employed, keeping the operation lean.

Many riders I’ve spoken to welcome the flexibility this brings, but the lack of protections are all too stark when only pedestrians are left to help you. One Deliveroo rider who fell off his motorbike and broke his hip – while rushing to complete 15 orders in the rain – told me a few years ago that the company neither provided sick pay nor revised safety measures: “They don’t care if it’s raining, if it’s snowing, or if ice is coming from the sky.”

4— “Ron DeSantis has built his brand on shifting the culture war from a war of position to a war of manoeuvre.”

That terminology, about Ron DeSantis’s nascent campaign to become the Republicans’ presidential nominee, draws from the work of the Italian Marxist scholar Antonio Gramsci. Seeing Gramsci and DeSantis mentioned in the same sentence might seem rather odd – until you read Alberto Toscano’s essay on how the Italian leftist became a favourite thinker among the strategists of America’s New Right.

The recent upsurge in right-wing invocations of Gramsci is an instance of that fear and imitation of radical theories that has long defined the right and its counter-revolutionary self-image. It comes with the frisson of rebellion. As Hochman proposes, “the right will have to become comfortable thinking of itself as an insurgent outsider in American culture, just as the Gramscian vanguard was before the 1960s”.

Long before the text-based illiteracy of social media panics was a thing, the US right had already turned Gramsci into a meme. The latter bears roughly the same relationship to the nuanced, open and militant method of the Prison Notebooks as the adjective “Machiavellian” does to the Renaissance political philosopher’s Discourses on Livy. It is hardly to be expected that intellectuals so intent on impeding reading and criticism should be good readers in their turn.

5—”Some think ‘woman’ doesn’t mean ‘human of the female sex‘ but rather ‘human that a heterosexual man might like to have sex with’.”

Try this essential Ellen Pasternack’s review of Victoria Smith’s book, Hags: The Demonisation of Middle-aged Women, which searingly describes the way women are treated as they age.

Ageing is not the same for women as it is for men. Men might fear death, and the frailty and weakness that comes before it. But for women, long before the onset of old age comes something just as fearful: a precipitous and irreversible loss of status.

Women in middle age are far from elderly; most of their adult lives are still ahead of them. But, says Victoria Smith in Hags: The Demonisation of Middle-aged Women, once women are no longer young they are inevitably seen not only as past their expiry dates but also annoying, useless, entitled and embarrassing. Oh, and ugly of course.

Patriarchal narratives state that what Smith terms the “three Fs” (“femininity, fertility, fuckability”) are what women are for. A woman who loses these while remaining not only alive but perhaps even thriving and assertive is an affront, a glitch in the matrix – like a car that stops driving and “has started talking instead”. When confronted by this, we face a choice. We can update what we think a car is (it turns out cars don’t just drive – they can talk as well!), or we can attack or ignore the talking car, perhaps denying that it is a car at all, because Cars Don’t Talk.

6—“I think a Trumpist winning in 2024 would raise questions about the viability of capitalist democracy.”

I interviewed Larry Summers, the longtime technocrat behind Democratic presidents, who appears to be moving left as he ages (like his friend Martin Wolf, the FT columnist). Summers once served as Bill Clinton’s Treasury secretary and was chair of Obama’s National Economic Council. He was also the Harvard dean who told the Winklevoss twins (the Winklevii?) that he couldn’t do anything to stop Mark Zuckerberg stealing their idea for Facebook in The Social Network (2010).

Summers became chief economist of the World Bank in 1991, at the age of 36, eight years after becoming one of the youngest tenured professors in Harvard’s history (Summers started his degree at MIT at 16). Academic brilliance ran in the family. His father’s brother was Paul Samuelson, the “father of modern economics”; his mother’s brother was Kenneth Arrow, another Nobel prize-winning economist. Summers lacks a Nobel of his own – unlike his great contemporary and rival, Paul Krugman – but is famous for his abrasive intellect. “Larry’s impressed by no one and never was,” a fellow economist told the New Yorker in 2009.

Elsewhere on the New Statesman

Politics Michael Crick suggests that instead of appointing Sue Gray as his new chief of staff now, Starmer should have waited, were he to win power, to “ease out Simon Case – probably the worst cabinet secretary we’ve ever had” and appoint Gray as the first female cabinet secretary in history.

Politics “On this reading, the era of Truss and Sunak is a strange reversion back to a politics killed in 2019.” Freddie Hayward watched the mischievous Michael Gove, the great survivor of Tory politics, align himself with Starmer this week.

US politics “Chris Christie’s law of politics was a good one, and I’ve been thinking about it ever since. One: Generic Republican beats Generic Democrat… Second rule: Biden beats Trump. Not only in 2020, but in a rematch. Meaning the Republicans had a problem, because of the broader Rule Three: Generic Democrat beats Trump Republican.” Ben Judah reports from Washington on DeSantis’s prospects in 2024.

Scotland Chris Deerin, our Scotland editor, who a year ago wrote The Profile to read on Kate Forbes, has two new pieces. In this week’s magazine, he looks at why Forbes may yet replace Nicola Sturgeon as Scotland’s first minister, despite controversies over her religious beliefs. He also argues here that all of the SNP’s leadership candidates, including Forbes, are wrong to act as if independence is imminent.

TV Try Amelia Tait’s whippy piece on the “abject copaganda” of Happy Valley, a show that “reassures you: don’t worry, the accountant who orchestrated the kidnapping of a young woman is now being raped in prison!”

Film “When you’re sold as a sex symbol, the message men get is that they can touch you, that they own you… because you’ve turned them on.” Sophie McBain on the objectification of Hollywood sex scenes.

Books Tomiwa Owolade takes a look at Nigel Biggar’s whitewashing of the British Empire. “Biggar’s book is worth reading. It is fascinating because there are two authors at work: Biggar the historian and Biggar the polemicist. They are very different.”

Economics Simply being a friend to business isn’t enough for Labour, argues Mariana Mazzucato in a new piece for us.

Best of the rest

The end of the English Major (Nathan Heller, New Yorker)

History’s Fool: The long century of Ernst Jünger (Thomas Meaney, Harper’s Magazine) More evidence that Thomas Meaney can write about anything and make it sing.

Will ChatGPT make cheating in exams the norm? (Suzy Weiss, Free Press) Uh oh. AI is helping students get “better grades for less work than ever”.

How Ozempic is changing the definition of being thin (Matthew Schneier, The Cut)

Emmanuel Macron: the endgame (Arthur Goldhammer, Tocqueville 21)

Ron DeSantis won’t hurt you (Damon Linker, New York Times)

The worlds of Italo Calvino (Merve Emre, New Yorker)

Why the Lab Leak will haunt us forever (Daniel Engber, Atlantic)

Inside the UK’s Mormon bootcamp (Harvey Day, BBC)

You will worship the bison again (Nathan Beacom, Plough)

The politics of founding a crypto-state (Adina Glickstein, Spike Art Magazine) “Contemporary culture sucks because where we once had virtue, we now have vlogs.”

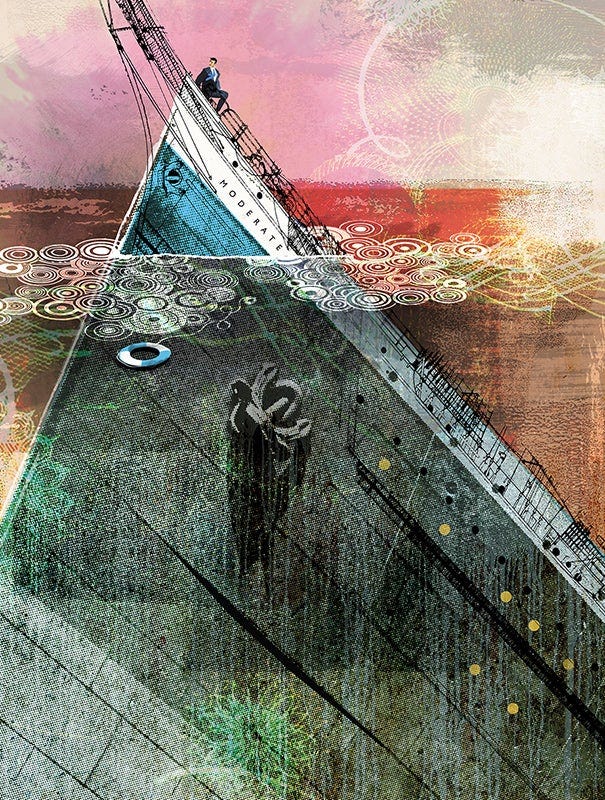

Audio long read: “The strange death of the centre right”

This week’s audio long read is brought to you by New Statesman writer-at-large Jeremy Cliffe. In Western democracies conventional conservativism is foundering. How did this once-dominant political force become so diminished? Listen via the link, or read Jeremy’s recent cover story here.

And with that…

Will here. Right, well that is it for the inaugural edition of the Saturday Read. If, after all of the above, you are looking for yet more essays, reports, interviews and provocations to read, then head over to the New Statesman.

This week I’ve spent far too long reading about the European Union, particularly Luuk van Midelaar’s The Passage to Europe and Peter Mair’s Ruling the Void. There are only so many times you can see the word “subsidiarity” without wanting to scream.

Brussels is mere miles away from the site of Waterloo, so after my time haunting the EU’s museums, I headed to the battlefield. The muddy terrain was suitable for frogs and not much else. Part suburbia, part damp farmland, Waterloo reminded me of how sad and warred-over Belgium has been through its history. As irritating and obscure as the EU can be, it exists to prevent days like Waterloo from ever happening again.

Thank you for reading. Don’t miss out – subscribe to the New Statesman and stay up to date with everything you need: from news and analysis to comment and criticism.

Whether you’re looking for a sharp blog or a finely written feature, the New Statesman has you covered. Have a good week, and catch you next Saturday.