The Saturday Read: #30

Inside: Great powers, effective altruism, election games, New York, and a new play.

Good morning, and welcome to the Saturday Read, the New Statesman’s weekly guide to the best writing on ideas, politics, books and culture. This is Harry, along with Will and Pippa.

It’s been a big week. Rishi Sunak diluted the government’s net zero goals live from Downing Street, sidestepping parliament and skipping the UN General Assembly in New York. Oliver Dowden attended in his place, and enjoyed an evening of drinks in the £12m, 38th-floor apartment that houses the British consul general here.

Volodymyr Zelensky was nearby in Washington DC, and might just have secured the long-range missiles he has been seeking from President Biden for months. A sitting US senator (Democrat, New Jersey) was indicted on bribery charges. Ibram X. Kendi’s center for “antiracist” research is being investigated. Shawn Fain, America’s Mick Lynch, is leading the United Automobile Workers into a growing strike. And the US government is heading for its latest shutdown.

Today’s sign-off is on heady New York book launches. If this email cuts off before you reach it, you can click through to read it in full online. If today’s pieces intrigue, perhaps you might like to try a trial subscription to the NS. (Almost everything in today’s run touches on the same theme: the ebbing away of power.) Read three free articles after registering on our site. A digital sub is only 95p a week. Let’s get to it.

1—“Could the cosy assumption of long-lasting peace between the great powers be wrong?”

For our cover story this week, the historian Paul Kennedy revisits his classic 1988 work The Rise and Fall of the Great Powers. A bestseller that, as Christopher Hitchens noted at the time for the NS, could be seen “spilling out of briefcases” in DC, it would later be found among the reading material in Osama bin Laden’s compound in Abbottabad. How have the relationships between the great powers changed, 35 years on? WL

Can the US, whatever its strengths, stay ahead everywhere in an era when both relative productive strength is shifting to the east and there is a general devolution of international power? If it cannot, then from which areas of the globe should it pull back? How should it manage its relative decline? That was the question asked in the closing chapter of Rise and Fall, and the fact that for the past three decades the world order has been relatively stable does not make the issue any less pertinent.

If a newer order of things tilts to America’s disadvantage, could the US make hard choices about where to withdraw? Number-one powers that sprawled across the globe in the past – imperial Spain, Edwardian Britain – found it near impossible to prioritise their assets and obligations.

2—“Alongside the extreme do-gooders, effective altruism has long fostered a darker, millenarian streak.”

Effective altruism is a philosophy that asks: how can I best use what I have to help others? Rather than trying to change greater systems of power, it works within them – a radical movement that bankers and billionaires can buy into. But now its king, Sam Bankman-Fried, is facing trial for fraud, can the movement survive? PB

The story of how the Oxford philosopher William MacAskill and the effective altruism (EA) movement found itself entangled with the disgraced Sam Bankman-Fried is partly about moral principles. Why should someone like Bankman-Fried find EA’s ideology so compelling – or at least convenient? But mostly it is about politics, the corruptive influence of power and money – the unforeseen (but not unpredictable) consequences of telling people that the best way to do good is to get rich.

3—“Every so often Stewart flicked a smart, adhesive glance at my notebook, before looking back to the car window, and the green fields that passed silently by.”

I spent many hours with Rory Stewart driving from Scotland down to Manchester, and then on to London, as he began a promotional tour for his new book. WL

When we stopped at a motorway services in Gretna, people recognised Rory Stewart. They either scuttled away, or approached him to say how wonderful he was. He has this in common with Boris Johnson: ordinary people admire him and think he is their friend.

Immense unease radiated from him, as unmistakable as the smell of burnt toast. Three hours into our journey, what surprised me most was how damaged Stewart was. In our conversations he described himself as “tortured”, “complicated” and “very, very different to the person who started in 2010”. Stewart seemed to be paying the price for not becoming the leader he thought he was. How did it feel when the public saluted him? “It’s disturbing,” Stewart said. People felt like they knew him but they didn’t.

4—“An election this spring has never seemed likelier.”

I’m still not sure that makes it likely. (If I was Rishi Sunak, I’d keep the plane and the power for another six months: why head to the exit early?) But Andrew Marr has heard that No 10 is entertaining the possibility of a spring election. He lays out the case for “going early” here. (Andrew also turned to how Labour might need to govern in his column.) HL

The truth is that the differences with 1992 are as great as the parallels. Those big opposition leads came towards the end of Margaret Thatcher’s premiership and by the time of the 1992 election, Labour was only slightly ahead. Brexit, the experience of Boris Johnson and the Truss explosion have reshaped politics today. The Tory press is unlikely to be quite as vicious to Starmer as it was to Neil Kinnock. Historical comparisons are colourful but sketchy, unreliable guides.

Yet this one is transfixing both the Labour and Conservative leaderships. Even as they bring in the latest detailed – appalling – polling for the Tories, people close to No 10 are excited about the theatrics of an early, unexpected “small boats election” and Sunak “doing a Major”. Labour is still psychologically scarred by 1992.

Sign up to our weekday political newsletter here:

5—“Keir Starmer’s attempt to rewrite the UK-EU relationship is based on a delusion.”

Wolfgang Münchau picks apart Labour’s new line this week: that a new deal with Europe is possible. (Anoosh has imagined a world in which Britain didn’t leave the EU in this interview with economist John Springford. The upshot? More growth, trade and investment.) HL

Probably the biggest delusion yet to be unpicked is Starmer’s repeated assertion that a better deal with the EU is available. This is simply not true. There was a lot of vindictive commentary from the EU during the entire Brexit process, but the deal that was eventually agreed was a reasonable third-country trade deal. The two big remaining issues at the time have since been resolved: Northern Ireland and Britain’s associate membership of the EU’s Horizon science programme. If your bottom line is that you do not wish to rejoin the single market and the customs union, there really is not a lot more out there.

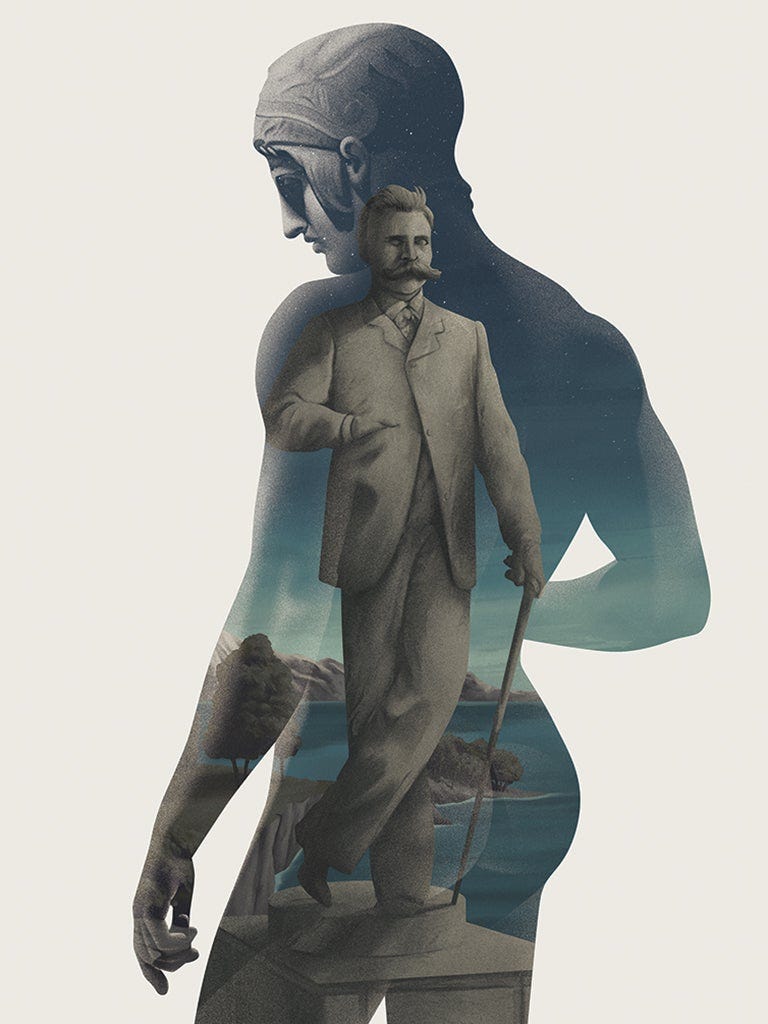

6—“BAP’s image of male predation, rapine and pillage is the fantasy of an aspiring teenage gang member in a disintegrating modern city.”

John Gray enters the world of Bronze Age Pervert, a pseudonymous, self-published reactionary author who, as well as being obsessed with the Hellenic world and Friedrich Nietzsche, is a major influence on American right-wing thought. Much has been written about BAP in recent months, but nothing quite as accurate as this. WL

BAP’s disdain for Christianity and the Enlightenment sets him apart from most other intellectuals of the right at the present time. The contrast with the much more widely known Jordan Peterson is telling. Like BAP, Peterson writes for those disenchanted with liberal culture and has attracted an audience of disoriented young men, but there the similarities end. The Canadian psychologist is a cultural conservative, who believes contemporary malaise comes from a rejection of Western traditions – notably the Christian religion.

For BAP as for Nietzsche, however, it is this very tradition that must bear some of the responsibility for liberal decadence: by making the Son of God a victim, Christianity began a revaluation of archaic pagan values that reaches a culmination in present-day woke movements. In this regard, BAP is a deeper and more dangerous thinker than any would-be conservative. Still, it will not be a celebration of Mycenaean pirates that fuels the next phase of American disorder.

7—“This Chekhov isn’t really about Chekhov. It’s about Andrew Scott.”

I went to see the opening night of Simon Stephens’ one-man Uncle Vanya adaptation and, in-between texting my editor celebrity sightings – Matthew Macfadyen! Nigella Lawson! – found Andrew Scott near superhuman. PB

We are experiencing a vogue for theatre as an endurance test: the multi-marathon-running Eddie Izzard taking on all 19 characters of Great Expectations; Ruth Wilson replaying the same scene over and over opposite different actors for 24 hours in The Second Woman. Scott faces less than both – just eight characters and 110 interval-less minutes – but still, his is a remarkable feat.

Will’s Best of the Rest

Times: Starmer promises he won’t undo Brexit. And he even said it with a straight face!

WSJ: South Korea would like some nuclear weapons. I wouldn’t mind a couple of nukes myself – for deterrence purposes, obviously.

Bloomberg: Zelensky showing the strain at UN.

Marina Hyde: Revisiting Russell Brand and Sachsgate.

Michael Wolff: Why Murdoch dumped Tucker Carlson. Running a ferocious right-wing media empire sounds genuinely exhausting.

Kelvin MacKenzie: The Rupert Murdoch I knew.

Becca Rothfeld: Why are public intellectuals so scared of the public? Possibly because the public are terrifying.

Tobi Haslett: Annie Ernaux’s spectacular impersonality.

The dolphin sex scandal that outraged a nation. One of the maddest stories of the year.

Elsewhere on the NS

Lewis Goodall has you covered on the political development of the week: Rishi Sunak’s weakening commitment to net zero. The PM is, Lewis writes, dancing to Nigel Farage’s tune.

Walter Isaacson’s Elon Musk biography sold 90,000 copies in the US this week (a far cry from the 380,000 that Isaacson’s Steve Jobs biography sold in its first week in 2011). Quinn Slobodian reviewed the 600-page tome here.

Mark Fisher was not Russell Brand, writes Matt Colquhoun. The pair were linked in the aftermath of Brand’s disgrace this week, as the critic and cultural theorist had defended the comedian in a long essay shortly before Fisher’s death in 2017. (Finn McRedmond wrote on Brand more directly here, for this week’s magazine.)

Kara Kennedy meets Jordan Peterson’s carnivorous daughter Mikhaila. There are quite a few alarming details in here.

Anoosh Chakelian: once again, the world turns away from Armenia, the country of my ancestors.

Elton John’s long-term collaborator Bernie Taupin may be a great lyricist, writes Jude Rogers, but he’s a poor writer of memoirs.

In the wake of Jann Wenner’s expulsion from the board of the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame this week, Fergal Kinney suggests it’s time to scrap “this self-congratulatory country club”.

Will Dunn on the deceits of the GameStop “short squeeze” movie Dumb Money.

Endurance, pain, Marina Abramović – another splendid Michael Prodger essay.

And with that…

New York is a city of book parties right now. On Saturday Michael Bloomberg hosted Walter Isaacson in his own home to toast Isaacson’s Elon Musk biography. On Wednesday Michael Wolff launched his new Fox News book, The Fall, the day before Rupert Murdoch handed operational control of his media empire to his son, Lachlan.

In between those two news-surfing releases, a third book was celebrated here on Tuesday night when Graydon Carter hosted Gay Talese – the famed New Journalist, who is still writing and walking upright, impeccably besuited, aged 91 – at the Waverly Inn, the storied New York restaurant Carter used to run. (Carter would pore over the seating each night, ensuring everyone who mattered had the right table.)

Talese’s latest book, Bartleby and Me, a captivating retelling of his journalistic career that builds up to a rich new story set in New York, brought high society together. I arrived early, early enough to shake Talese’s hand soon after he turned up. He asked me if I was “in charge” before walking off briskly when I demurred. I’ll take it: reading Talese’s Paris Review interview late one night in the university library when I was 21 is pretty much what made me want to be a magazine writer.

I later introduced myself to David Remnick, which went better than the first time I met him. I wasn’t sure what to say to Nick Pileggi (the late Nora Ephron’s husband, who wrote GoodFellas), and didn’t spot the New York Times’s Maureen Dowd or the artist Frank Stella, who were both apparently present. I was preoccupied plying a series of whiskey sours out of the barman for a $20 tip. The Washington Post described the night as “a glimpse of New York’s literary golden age”. The kind publicist who let me in said he hadn’t been to such a party in years. I’m not sure I ever had.

Thank you for reading. Don’t miss out – subscribe to the New Statesman and stay up to date with everything you need: from news and analysis to comment and criticism.

Whether you’re looking for a sharp blog or a finely written feature, the New Statesman has you covered. Have a good week, and catch you next Saturday.

Thanks to Chris Bourn and Pippa Bailey.