The Saturday Read: Should Britain be a republic?

Inside: Charles' soul, Britain's ills, Westminster's flaws, the locals, the octopus and God.

Good morning, and welcome to the Saturday Read, the New Statesman’s weekly guide to the best writing on ideas, politics, books and culture. This is Harry. If you are receiving this email for the first time, we are now sending the Saturday Read to readers of our ideas & letters and international newsletters, in place of those. Each week we will send you a mix of essential NS reads and links to pieces elsewhere, along with a few other snippets. We hope you enjoy this email.

Should Britain become a republic, Will asks in today’s sign-off. It was the first question I ever debated at school, aged 12. I can’t remember which side I was on, but I am a restrained monarchist now. I’d reform many things about the royalty (could Charles pay inheritance tax please), but I think an elected head of state an unnecessary constitutional innovation. I can’t see the merit in an elected House of Lords either (what we need is more crossbench peers and an end to cronyism; don’t tell Gordon Brown). What really ails our nation? Not the monarchy, I’d argue. Our writers have offered some of their own answers to that question in today’s picks.

If the pieces below intrigue, you could try a trial subscription to the NS. Read three free articles after registering on our site. A digital subscription is just 95p a week. Let’s get to it.

1—“It was still not clear: why did the King keep returning to Transylvania? The diplomat blinked. Wasn’t it obvious?”

The coronation procession is about to begin. For the first time in 70 years, a new British monarch is about to be crowned. But who is the king? Will has written The Piece on Charles. He went to Transylvania to find the man’s soul, returning with a 6,000-word epic of a story that runs as our cover this week, and reads almost like a fairytale. Do try it. (You can also listen to Will’s piece as an audio longread.)

The prince learned to escape into the Caledonian pine forests. He learned to mark individual trees, and the habits of grouse and red deer, and how to spot the butterflies that haunted the heather. Eagles circled above him. He was taught how to shoot most of these creatures with a rifle. When the prince returned to his castle after a day’s fishing, red-coated footmen bowed to him, just as he bowed to the bronze statue of his great-great-great grandmother Queen Victoria in the grounds. He had everything here. He could sleep soundly. Other boys would not creep up on him, like they did at boarding school and pull at his (already famous) ears.

As he grew older, the prince learned that he had arrived late. Balmoral was the lonely remnant of a vanished age, when the Highlands were covered with trees, before the devastation inflicted by the clearances of the 18th century, when the pines were murdered for their timber. The prince learned that history had, somehow, gone wrong.

2—“Alongside poor growth, the recuperating patient suffers from poor circulation.”

Andrew Marr has reflected on the state of the nation. His address reads as a refreshing river between the remorseless negativity of the left and the mindless boosterism of the right. Britain isn’t growing, it’s deeply unequal, we lack a manufacturing base, and “our rivers and beaches are filthy”. But there are green shoots too, especially if Labour had the courage to tax wealth in order to fund investment, Andrew argues. He also addresses our current moral reckonings:

We have gone from the purblind, rosily self-indulgent view of the empire when I was growing up in the 1960s, as a benign spreader of the rule of law, railways and the principles of Whig parliamentary democracy, to more or less its opposite: an entirely grim account of a murderous, hypocritical and racist land-grab by psychopaths in wigs.

The way through is a patient, open-minded historicism, which weaves together the stories of the colonised, alongside the colonisers; those from whom land was taken as well as those who took it. It would follow the money, and take due account of the destruction of vital records as the empire retreated. In this accounting we will find that the British, alongside every other dominant nation in history, used a temporary technological and organisational advantage boldly and selfishly to exploit less advantaged peoples for their own enrichment. The speed of industrial advance at the time made our story more dramatic, but it isn’t an unusual one.

You might also like Andrew’s piece to camera on why Labour need to start talking about immigration.

3—“The strange thing about parliament is how incidental it feels so much of the time.”

I reviewed Ian Dunt’s new book on Westminster, the publishing world’s latest take on the many problems with the way power is wielded in Britain. “Another one?” Will protested, when I told him about it. But this one is good. (I also wrote about being a lobby journalist, and why I found it strangely dissatisfying.)

“The most harrowing thing” about Chris Grayling, Dunt writes, “is that he is a completely standard example of the quality of the ministerial class in Britain.” But this book is more than a harangue about why we get the wrong politicians. It explains, chapter by chapter, the classes of people who hold political power in the UK: from the voters (once in a while) to parliament (barely at all), the prime minister (less than you think), cabinet ministers (more than you think), the Treasury (just as much as you think), the civil service and the press.

Most of the time, the formidable reporters of Westminster are only focused on stories that fall into one of three boxes: Tory-Labour fights, intra-Tory fights and intra-Labour fights. If an issue does not fit into one of these boxes – the disastrous rise in homelessness over the 2010s, for instance – politicians can usually get away without being scrutinised.

4—“What happened to the swans – have they been cleaned up?”

Anoosh, our Britain editor and lead podcast host, travelled to Bracknell Forest ahead of Thursday’s local elections. It’s a lovely piece of on-the-ground election reporting of the type the NS has been doing for the past decade. Dispatches like these give you a feel for the atmospheric pressure, or social temperature, of the nation.

Bathed in robin song and the hum of electric hatchbacks, even this wealthy enclave of the Home Counties has succumbed to the Blue Wall blues. Residents complain about their local surgery, which is in special measures; the potholes; and sewage flooding a local park, scout hut and allotments – polluting the river Blackwater and a swimming spot called Horseshoe Lake.

“When they really need the state – when the roads fall apart or their mum or nan needs social care – that’s when these people get angry,” Forster told me. “The Tories are scoundrels!” remarked another resident, her head popping up from where she knelt potting in her flowerbed. “I think we all need a change.”

5—“These writers care about language and good literary style.”

Our editor, Jason Cowley, was in Edinburgh this week for the Baillie Gifford prize for non-fiction’s winner of winners award. The prize was celebrating its 25th anniversary and, as the chair of the judges, Jason announced the winner: James Shapiro’s 1599. Judging a literary prize is not without its perils, though.

I never tire of visiting Edinburgh, one of my favourite cities and surely one of the world’s greatest. I love the ordered formality and wide streets of the Georgian New Town; the architectural grandeur that awaits as you emerge from the lower depths of Waverley Station; the absence of security barriers outside Bute House, the First Minister’s official residence on Charlotte Square; the sounds of the distant seagulls in the skies above, and the presence of the castle on the rock that looms but never threatens or menaces as Kafka’s did.

Shortly after I’d announced the winner, returning to my table, I felt a tap on my shoulder. It was Margaret MacMillan, no less. “Congratulations,” she said. “Really, so well done!” Thank you, I said, standing to shake her hand. Then her expression changed. “I’m so sorry. I thought you were James Shapiro.” With that, she was gone.

6—“Step up Dominic Cummings.”

It is a charming feature of the British system that we dispose of our political leaders with haste. Boris Johnson is already a distant memory – the prime minister one before last, even. Do we really need a book about his sordid premiership? Yes, David Gauke argues convincingly, in his review of Anthony Seldon’s Johnson at 10 – a book that cracked the top five on Amazon last week. We plainly remain fascinated by how one man threw away so much power so quickly. What Seldon’s book reveals is quite how bad Johnson was at actually doing the job.

Based on interviews with more than 200 witnesses of Johnson in office, his weaknesses are exposed again and again. His thinking is “shallow”, he lacked “focus and grasp” and had a “chronic inability to initiate difficult conversations”. Described as “woefully inadequate at governing”, he “would chair meetings chaotically” and had a “short attention span”; he was “biddable” and “often unserious… and lacking any kind of grip on the machine”.

7—“There’s really no commercially viable way to humanely kill an octopus.”

Consider the octopus, writes India Bourke, as the Spanish seafood firm Nueva Pescanova prepares to open the world’s first industrial-scale cephalopod farming facility in the Canary Islands. According to documents leaked to the BBC, it aims to produce as many as one million octopuses a year inside a two-storey building.

These creatures would not be the first, of course, to enter such an intensive system; hundreds of billions of chickens, pigs, cattle and other species have gone before them. But, as Dr Andrew Crump of the Royal Veterinary College explains, octopuses’ behaviour is highly unsuited to captivity. From the way they jet-propel themselves away from danger to the cannibalism (and even self-cannibalism) displayed when kept in crowded conditions, these “great apes of the invertebrate world” are far from conventional livestock. “There’s really no commercially viable way to humanely kill an octopus that we know about,” Crump said – a view shared by many other biologists.

8—“Many of the problems with our diets are so obvious that even Donald Trump has intuited them.”

Artificially produced foods are making us unhappy and unhealthy. Sophie McBain investigates the world of ultra-processed foods (UPF), engineered for what experts call “hyper-palatability”.

“This is food engineered to override your appetite: you eat so fast you don’t notice you’re full. UK dentists report more overbites in children because modern convenience foods require so little chewing. It’s also food that hoodwinks your senses: when we register the umami hit of a cheese-and-onion crisp, our brains expect something rich and satisfying, not a sad mouthful of starch. Ice cream is too cold to smell, and so some manufacturers use caramel-scented wrappers to prime consumers.”

9—“It is far more reasonable to have faith in a divine mystery than in humankind.”

Philosophers and comedians don’t often mix, put perhaps on the evidence of this John Gray review, of David Baddiel’s new book about God, they should do so more.

The beauty of Baddiel’s paradoxical book is that, after admitting his attraction to a God that offers deliverance from death, he confesses he loves his ancestral religion for its unceasing struggle for life in this world. “If I am moved by Jewish survival,” he writes “I am moved by Judaism. There’s no getting around it.” He has no need to regret the absence of a death-denying God. The story of survival is enough. But if there is inconsistency here, it is more than forgivable. Baddiel’s contradictions are like his jokes – pointers to truths that bring us back to earth.

10—“Human beings interpret the world. Only God could change it.”

Madoc Cairns writes deftly on Jacques Maritain, the “Red Christian” who, more than any other thinker, reconciled Catholicism and democracy. Maritain is sometimes called “the father of Christian Democracy”: he’d likely dispute his parentage. In 1966 “he dismissed Christian politics since the war as a failure”. What would he say in 2023?

“Joe Biden, in his own way, reflects both the success and the failure of Maritain’s project. The second Catholic president of the US, publicly comfortable with his faith as JFK never was, he’s proof that Maritain’s vision of a Catholic modernity took root, however imperfectly. But in his embrace of the market – and his tendency to keep his faith at arm’s length politically – he demonstrates how shallow those roots were. In this sense, Biden is the last Christian Democrat. It seems likely he will have no heirs.”

Best of the Rest

Economist: The Tories versus the institutions.

BBC: Joanna Cherry – why I am being cancelled. She might be the one person in the SNP having a worse time than Nicola Sturgeon.

Cleveland Review of Books: The American conspiracy canon.

Sixth Tone: Chinese migrants don’t like Sweden. It’s what they have in common with Karl Ove Knausgaard.

Guardian: Overworked chatbots forced to farm content. When will they unionise?

Heidi Blake: The fugitive princess of Dubai.

Tina Brown: Photographing England’s last hurrah.

Yvette Cooper: There is no plot against Yvette Cooper.

Rachel Cusk: Annie Ernaux’s honesty.

Leah Finnegan: Traffic jam. Click through for the superb Steve Bannon anecdote.

Strong contender for the worst animal to be eaten by revealed.

Elsewhere on the NS

“Who wouldn’t want to lose their virginity to David Bowie?” Lauren O’Neill reviews the groupie, the quasi-mythical figure of rock music lore.

Fergal Kinney explains why Nick Cave now fits right in with crashing reactionary bores.

“Whoever is leading the Tory party in 20 years’ time could take Britain back in to Europe.” This piece reminds me of what I take to be Dominic Cummings’ most appropriate fate: running the Rejoin campaign in 2045. (He’ll be 74.)

Ellen reviews a playful, wondrous new novel by Catherine Lacey, in which she invents a figure who knew Acker, Sontag, Waits, Bowie and the rest.

The US controls the world’s economy by controlling the world’s reserve currency. Wolfgang Münchau fears they are, through heavy-handed sanctions, overusing that privilege. Russia/China hawks will disagree.

“After peaking at 71 per cent in 2003, the share of owner occupiers in England has fallen to 64 per cent, a lower rate than in 1987.” As the inimitable Jonn Elledge used to say each day when he worked at the NS: build more houses. Our Leader this week picks this up.

How to get into: Russia-Ukraine

Each week we ask someone to recommend three books as a way into a subject. This week we asked Ido Vock, our international correspondent, where to start on Russia-Ukraine.

Secondhand Time by Svetlana Alexievich (2013): To understand the roots of Russian revanchism, read Alexievich on how the people of the Soviet Union were told overnight to believe in the opposite of everything they knew. No book better explains the hope, despair, trauma and sense of opportunity presented by the Soviet collapse of 1991.

Chernobyl by Serhii Plokhy (2018): The 1986 Chernobyl catastrophe was one of the decisive factors in the state’s collapse five years later. Plokhy’s account of the disaster is a gripping read about an episode that will mark the geography of Ukraine and Belarus for centuries to come and still has echoes today, as the ill-fated Russian occupation of the plant in 2022 has shown.

East West Street by Philippe Sands (2016): Over the past century, the flag flying over the now western Ukrainian city of Lviv changed no less than six times: Austro-Hungarian, Ukrainian, Polish, Soviet, Nazi, Soviet and finally Ukrainian again. Sands’s book is about two pivotal figures in international law, Hersch Lauterpacht and Raphael Lemkin, but the city of Lviv (or Lemberg, Lvov or Lwów) is as much a character as either of the two lawyers.

What we’re reading

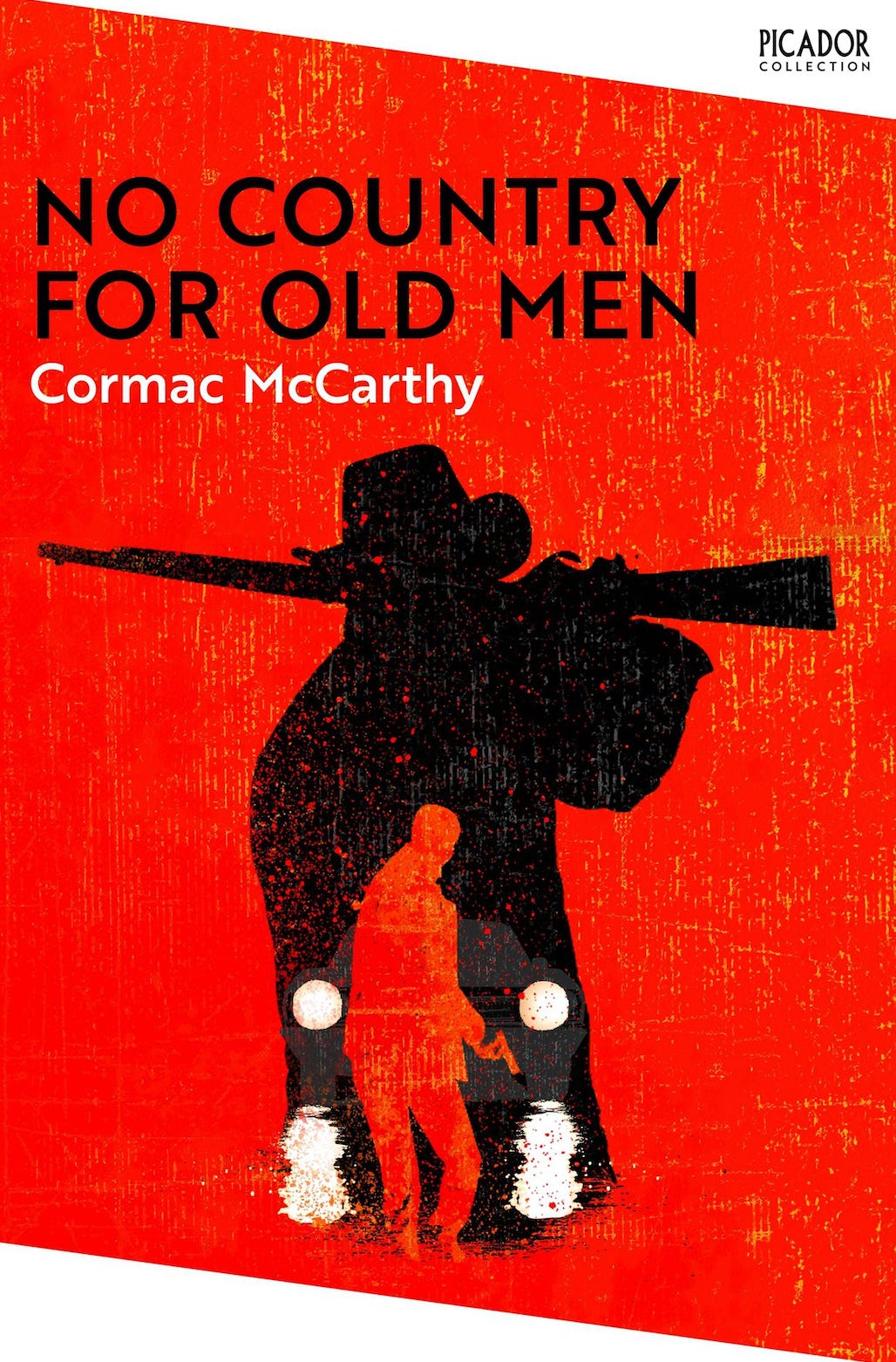

“The papers said it was a crime of passion but he told me there wasnt no passion to it. He told he’d been planning to kill somebody for about as long as he could remember. Said that if they turned him out he’d do it again. Said he knew he was goin to hell. Be there in about 15 minutes. I dont know what to make of that. I surely dont.” I’ve been reading No Country for Old Men by Cormac McCarthy (2005), whose punctuation-less sentences hold you in their grip. If you liked the film, one of the best of the 2000s, you’ll love the book.

This week’s letters (“Which book changed your life?”)

Lily: This Song Will Save Your Life by Leila Sales was instrumental in helping me get out of my nervous breakdown at university. I’ll always be grateful to it for helping save – and therefore changing – my life.

Anton Cebalo: In my life, Brothers K [The Brothers Karamazov, by Fyodor Dostoevsky] for sure. As for more recently, All That Is Solid Melts into Air: The Experience of Modernity by Marshall Berman really deepened my understanding of modern history and what it means to live in our time.

David L. Babcock: The Road Less Travelled, M Scott Peck.

And with that…

I’ve spent the last seven weeks thinking about King Charles. Emails have gone unanswered (sorry), invitations declined (sorry) and friends ignored (sorry), while I tried to work out how Britain’s monarch sees the world and his place in it. Charles has rarely been taken seriously: his public life has been governed by seismometer-needle-like lurches between light mockery and heavy ridicule. I’m happy to be finished with him – for now – and pleased to get out of his head, because it is not, as I hope my piece this week demonstrated, an entirely pleasant place to be.

What I did not consider is the place of monarchy in Britain. Is it a toxic, antiquated force, which props up an injurious system of hierarchies that ought to have been abolished long ago? Or is the monarchy a gentle, non-sectarian sugar bath that Britain can safely dissolve its nationalist feelings in? Is it time to abolish the monarchy?

Well, Tanya Gold, Robert Hardman, Andrew Marr, Tanjil Rashid, Anna Whitelock and Gary Younge – assembled by the New Statesman at the Cambridge Literary Festival – debated that question last month. The full transcript is available to read here. Gary described the absurdity of the hereditary principle: “His CV is his DNA.” Andrew argued that a “fragile” Britain is in no fit state to roll out the guillotine. Tanya paraphrased Oscar Wilde: “One unhappy royal is an accident, two is carelessness.” What do you think? Let us know in the comments below.

Thank you for reading. Don’t miss out – subscribe to the New Statesman and stay up to date with everything you need: from news and analysis to comment and criticism.

Whether you’re looking for a sharp blog or a finely written feature, the New Statesman has you covered. Have a good week, and catch you next Saturday.

Thanks to our colleague Chris Bourn on this week’s edition.

The British Monarchy is an antiquated institution that has no place in a 21st Century Democracy.

Should be immediately abolished, preferably under a new Written Constitution!