The Saturday Read: Heading west

Inside: Europe's turn, Keir's restraint, Farage, new MPs, Amis, Levy, and with that…

Good morning. Welcome to the Saturday Read, the New Statesman’s guide to politics, culture, books, and ideas.

Programming note

This is my final SR. From next week Jason, our editor-in-chief, will write to you each week alongside George, Finn and Nick. I too am heading west. I hope you have enjoyed receiving this email over the past 15 months; I have enjoyed sending it to you.

I started the Saturday Read with Will Lloyd last year as a way of sending out a Saturday paper that distilled the week’s news with some character. Today there are enough SR readers to fill Wembley Stadium, which is hard to imagine. We have always sought to send you a sharp mix of pieces. I’m sure that will continue. I have signed off with a few thoughts at the end of today’s email, along with a final poll. Thank you for reading. – Harry

1—“The hard right could win without winning.”

There has been some self-satisfied analysis in the wake of the European elections: all that fretting about the rise of the hard right wasn’t necessary – the centre has held! Hans Kundnani is not so sure. The argument only works if you ignore all the ways the centre has shifted slowly, but inexorably, rightward. (We have more on this here.) FM

After the Dutch election last November, when Wilders’s PVV emerged as the biggest party in the Dutch parliament, EPP leader Manfred Weber made it absolutely clear that he believed that, in order to see off the “populist” challenge, the centre right needed to show voters it could go even further to stop immigration. It is likely that the European centre right will now double down on this strategy of attempting to defeat the hard right by becoming the hard right.

2—“When people say this campaign is changing nothing, it isn’t true.”

Labour’s manifesto launch was a sober display of political rectitude – “I’m running as a candidate to be prime minister, not the circus,” said Keir Starmer in response to yet another accusation of excess caution. Andrew makes an equally cautious case for the “quiet revolution” Labour might still usher in through its reforms to tax and Britain’s relationship with the EU. NH

The deeper the collapse of the right and the bigger the Labour majority, the faster and more dramatic will be the impact of the coming government. There will be a change in culture and atmosphere that none of us can, yet, quite imagine. This campaign is turning the fast-flowing river of British political life into full spate – an acceleration so fast and frothing it can be hard to follow. Starmer has come a long way with a politics of cautious underpromising. But, as will soon become clear, that’s by no means the end of this story.

3—“The ingredients were all in place for Farage’s coiled contradictions.”

As Nigel Farage’s party begins to overtake the Conservatives in the polls, I sought to understand the strategic juxtaposition between Farage and the musical backdrop to his campaign – Eminem’s “Without Me”. Cultural clashes like this are, I think, the key to Farage’s political vibrancy. NH

He’s always liked living life facing both ways – which sets him up nicely for having things both ways too. He keeps a house in Downe, a village dotted just inside the M25, but just outside the “great wen” of London sprawl, where roundabout and corner shop give way to meadow and sky. To his back is the Kentish garden of England, and to his front the hyper-modernity of the metropolis… Now Nigel is back at it, combining the uniforms of the dynamic populist who knows a good backbeat with the trustworthy gent.

4—“To understand Labour’s future, you need to understand them.”

A collaborative effort this week as we profiled ten of the most interesting “Starmtroopers” – Labour candidates set to join the Commons at the next election. I covered and spoke to Tom Gray, who has set aside his Mercury Prize-winning turn as a guitarist to try and depose the Greens from their only parliamentary seat to date. GM

The “Starmtroopers”, as new candidates have been labelled, are sometimes assumed to be identikit Westminster insiders. But the individuals profiled here are striking for their diversity: an Afghan refugee and torture survivor; a Liberian-born economist; a British-Chinese author and former Financial Times journalist; a former RAF pilot and friend of Stephen Lawrence; and a Mercury Music Prize-winning indie musician.

To enjoy our latest election news and analysis with unlimited access to our coverage click here to subscribe to the New Statesman. You’ll enjoy all of the New Statesman online content, ad-free podcasts and invitations to NS events.

5—“What exactly does it mean to ‘write like a man’?”

Leonard Benardo defends complexity, arguing against a new theory that attributes the world-view of the New York Intellectuals (Daniel Bell, Irving Kristol, Irving Howe, Nathan Glazer et al) to an ideology of “secular Jewish masculinity”. Like that famed rat pack, this piece packs an erudite punch. GM

Grinberg inappropriately calls her master concept an ideology. The ideology of secular Jewish masculinity she repeats like an incantation as if to jackhammer in a conceptual innovation. But secular Jewish masculinity – whatever that may suggest in reality – is hardly an ideology. Maybe it’s a style, perhaps a description of a sort. Ideologies, however, are simplifying systems that reduce complexity to a limited set of assumptions and beliefs, often to reproduce a dominant social power. Secular Jewish masculinity, a confection divined by Grinberg herself, is retrospectively imputed to the New York Intellectuals. But ideologies don’t emerge through imputation. The book’s elemental flaw is in assuming secular Jewish masculinity to be a coherent perspective.

6—“In a decade 20-30 per cent of the population will be on these weight-loss drugs.”

This week’s runaway hit was Sophie on Ozempic – the medication for type 2 diabetes that has “hit Hollywood as the ultimate diet drug”. It’s easy to see why: it works. But what then? GM

I thought of how essential it is that the public conversation about food culture and obesity begins engaging with the emotional and psychological dimensions of the problem. Policymakers can talk endlessly about weight and waistlines and school dinners and sugar taxes and restaurant calorie counts, but they pay too little attention to how food, which ought to be a source of pleasure and nourishment and togetherness, has become the source of so much guilt and shame.

7—“Turning an exquisitely funny line is as important as diagnosing the condition of the nation.”

In a wonderful piece reflecting on Amis’s memorial service this week, held a year after his death, Tom Gatti lends his voice in service of Amis’ just war against cliché. NH

Think back to the works that have made the deepest impression on you: the plot and characters may have faded, but kernels of language remain. At any one moment, I find half a dozen lines wriggling under the topsoil of my brain… This may seem obvious, but it bears repeating because our culture risks losing its joy in language, abandoning the idea of words as units of pleasure.

8—”The source of all this rancour? The internet, duh!“

Martin Amis’s war against cliché is not over. This week I read My First Book by Honor Levy – the enfant terrible of Manhattan’s Lower East Side literary scene. It left me wondering: is it possible to write well about the internet? FM

But this is precisely how information is conveyed in cyberspace: a series of short text messages sent in quick succession; a flurry of videos on a TikTok timeline, aesthetically and tonally unconnected. My First Book is like an endless series of notification pings. The prose is as wearying as doom scrolling any Twitter feed – which is to say, extremely so. But we can’t hate internet fiction for sounding exactly like the internet. Otherwise we risk being like one of William F Buckley’s men who stand “athwart history”, begging it to stop.

George’s Best of the Rest

BBC: Macron gambles on election. This gives Rubicon.

Adam Nayman: On Richard Linklater’s films.

Peter Holslin: Vive Californication.

Michael Knox Beran: Abraham Lincoln, political poet. Give me six hours to chop a tree and I will spend the first four sharpening my iambs.

Hannah Zeavin: Writing a novel with the Internet’s Boyfriend.

Rhian Sasseen: Incredibly online and extremely tedious.

Meaghan Garvey: Review of Brat by Charli XCX.

Growing Philippines diaspora means worldwide party on Independence Day.

American tourist turns into failed Birmingham hit woman. You read that right.

I first joined the NS a decade ago this month, and have worked for it most of the time since then. In that time: Scotland stayed in the union, Cameron won an unexpected referendum-enabling majority, Britain slammed into the brick wall of Brexit, Farage was forgotten, May crumbled, Corbyn rose and fell, four parties all polled over 20 per cent in the summer of 2019, independent MPs effectively ran the country for a brief glorious window, parliament buckled after prorogation, the Johnson-Cummings project collapsed under the weight of Covid and its own contradictions, a fool and a man in schoolboy suits took over No 10, Keir Starmer rode a turning tide, Farage returned, and the Tories now face a 250-seat collapse.

There is nowhere I would rather have witnessed the past 10 years. In Britain’s formidable but constrained media world, dominated by strictly-sectioned newspapers and magazines written in a set house style, the NS is a place that lets its writers roam, in subject and style. I won’t top Will’s departing encomium. But if you’ve found the SR fun and useful over the past year or so, there’s an even better way to read it.

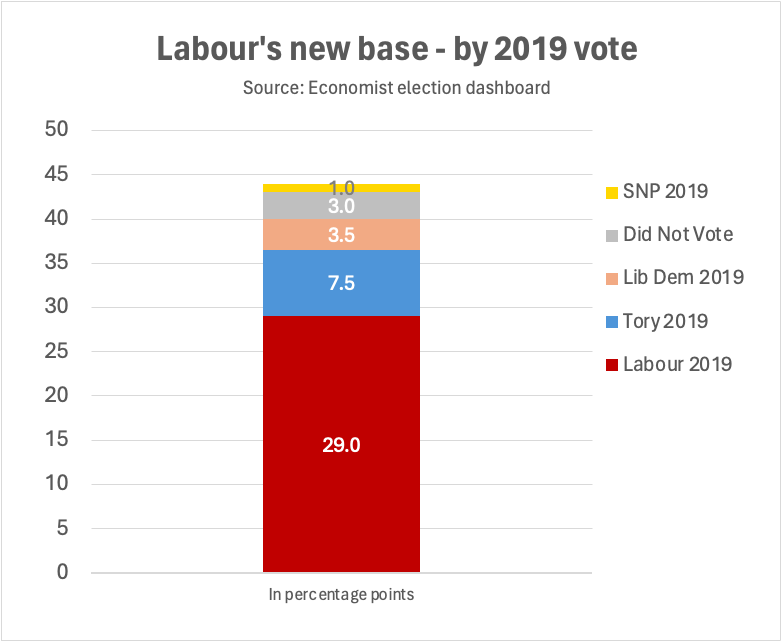

I’ll leave you with a chart. What’s ahead? Keir Starmer really is set to be atop an elective dictatorship. Yet few think he is going to govern from the left. A look at Labour’s new coalition helps explain why. This back-of-the-envelope sketch shows where the party’s support is coming from, divvied up by how people voted in 2019.

You can see two-thirds of its new vote is from 2019 Labour voters. But one-in-six voted for Johnson in 2019. I think they are going to be prized within the party like no one else. They are too valuable to Labour: hard-won, they will be reluctantly lost.

Appealing to the newly-red soft right could easily hem Starmer in on every issue. The government will change. But how much else will? HL

If today’s pieces intrigued, you can subscribe to the New Statesman below. Stay up to date with everything from news and analysis to comment, criticism and essays.

Whether you’re looking for a sharp blog or a finely written feature, the New Statesman has you covered. Have a good week, and catch you next Saturday.

The problem with The New Statesman for people like me in Scotland is that it views this nation as irrelevant to most UK political discussion and when it is mentioned, the writers see it through a Labour prism. The control of the media by Union-supporting factions makes it easy to disparage ambitions within Scotland to run our own country rather than the people next door doing so. Starmer sees Scotland as a source of voting foot-soldiers and much-needed resources for energy, water and a berth for nuclear weapons well away from places that matter. To many it looks like a British Empire mentality. Cynical? yes I am.

I vote SNP.

disappointed all the time about NS lack of interest in or respect for Scotland. unlikely to renew my subscription'