The Saturday Read: Saudi century

Inside: How MBS won, Tory PMs lose, and Barbenheimer came to be.

Good morning, and welcome to the Saturday Read, the New Statesman’s weekly guide to the best writing on ideas, politics, books and culture. This is Harry, along with Will.

We have an interesting array of pieces today. Watch out also for next week’s Saturday Read. It will be something of a bonanza, being full of pieces from our summer issue.

NB: If this email doesn’t load for you in full, you can view it online (or in app) by clicking on the button you see when your email cuts off. The email hasn’t ended until you reach the sign-off. Today’s is on the odd absence of the vital political speech.

If the pieces below intrigue, perhaps you’d like to try a trial subscription to the NS. Read three free articles after registering on our site. A digital subscription is only 95p a week. If you are already a subscriber, thank you for reading us.

Each week, around 100 people click through to subscribe. If you have become an NS subscriber via the Saturday Read, do get in touch and let us know how you are finding that. Let’s get to it.

1—“Watching from the North Atlantic, it is tempting to alternately laugh and shudder at Saudi Arabia’s plans.”

In this week’s cover story, Quinn Slobodian cuts the ribbon on the Saudi century. This new Middle Kingdom and its crown prince, Mohammed bin Salman, are reshaping the globe. Slobodian charts the reasons for – and the sobering consequences of – the country’s rise to power. WL

Since the rise of MBS, it has been difficult to transcribe the press releases from Saudi ventures without feeling like you’re penning short stories of speculative fiction. This is no coincidence. A confessed fan of science fiction, MBS has commissioned experts in the fantastic to help design his new national projects. In 2023 Saudi Arabia announced a real-life project that is twice as big: an ornately decorated cube called New Murabba, with every side 100m longer than the Shard. The cube will contain a tower and close to twice as many square metres of office and shopping space as the whole of Canary Wharf.

Yet even this “giga-project” is only a sideshow to Neom, a half-trillion-dollar, 10,000-square-mile city planned for the south-western corner of the Saudi peninsula. The project is billed in a sun-dappled promotional video as “a start-up the size of a country”. The most complete version is currently on display at the Venice Biennale of Architecture.

2—“It’s the sum total of the Tory soul at a point in time: ecstatic, sullen, enraged.”

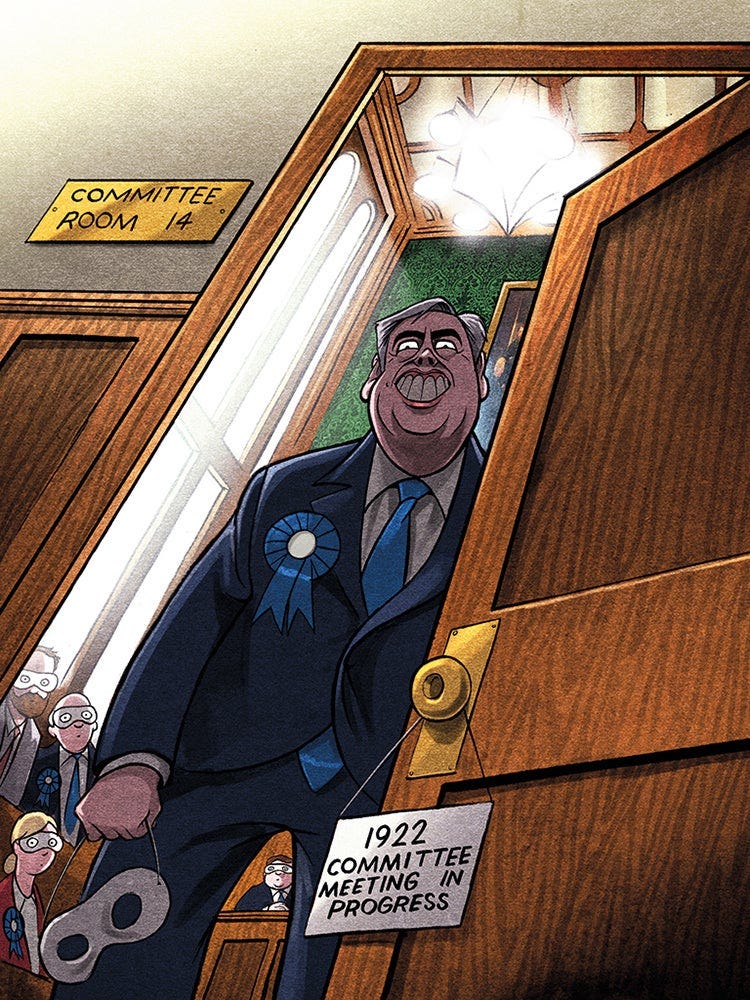

The Conservative Private Members Committee, informally known as the 1922 Committee, should perhaps be known by another name: the assassination bureau. Tanya Gold takes us inside the group behind the fall of the past three prime ministers, and asks when it will next provoke Tory chaos. WL

The Tories have a taste for theatre and the ’22 is the seat of their internal democracy, one of the backbenchers’ favourite playhouses. Its weekly meeting is held on Wednesday at 5pm in the neo-gothic horror of Committee Room 14 in the Houses of Parliament. The room is vast and high, walled in Augustus Pugin’s poisonous green paper. The carpet is a blinding collection of shapes; the seats of the executive look like a judge’s bench. Paintings of lost Tories line the walls, hung so high you cannot see their faces or read their names.

Since 2010 the Capo di Tutti Capi, or Head Prefect, or Chief Psychiatrist, or Nanny, has been Graham Brady, the MP for Altrincham and Sale West, though he recused himself in 2019 when he considered standing for the party leadership. (He changed his mind, and Johnson won.) Brady entered parliament in 1997 and resigned as a shadow minister for Europe over David Cameron’s opposition to grammar schools. (Brady was a grammar school boy.) His independence was soothing to MPs. The ’22 has never elected a former cabinet minister as chair.

3—“If anything, the Kremlin turned out to be even more timid and powerless in its response to Wagner than I first anticipated.”

Bruno Maçães, our foreign affairs correspondent, has spoken to a former Wagner commander, Marat Gabidullin, who says that Yevgeny Prigozhin’s recent march on Moscow was “quite predictable” if you know him. Prigozhin was not looking to depose Putin, says Gabidullin: “The objective was not a military coup but to ask Putin to choose between him and Shoigu. The turning point was when he realised that trying to get rid of Shoigu meant he had to overthrow Putin.”

Both Prigozhin and the Wagner Group remain formidable forces, which are seemingly beyond Putin’s control. HL

What we know as a matter of fact: Prigozhin has been travelling freely inside Russia, meeting the Russian president, and calmly making plans about the future. A Russian television network reported on 12 July that companies with known links to the Wagner Group have been awarded over 1 billion rubles (£8.4m) in government contracts in the weeks since the rebellion.

Over the weekend of 15 July a Wagner-affiliated account on the social messaging platform Telegram published a photo showing the arrival of new Wagner soldiers in Bangui, capital of the Central African Republic. On 19 July Prigozhin reappeared on video, addressing his fighters in Belarus in a clip posted online, saying that Wagner was gathering its strength and opening “new paths in Africa”. “We may return to Ukraine when we are not forced to disgrace ourselves there,” he added.

4—“A desperate party may be susceptible to bad ideas to recover its position.”

David Gauke, a Tory MP from 2005 to 2019, offers his take on this week’s by-election results: most of his former colleagues, he writes, will be terrified by them. (Andrew Marr provides a caveat in his piece: “The Conservatives thought this week could have been worse for them, and they are right.”) HL

Voters in all three by-elections were forced to the polls because of the failures of the respective Conservative MPs they elected in 2019. In one of the seats, the MP resigned in disgrace (David Warburton); in another, they resigned in a self-indulgent strop (Nigel Adams); in the third case, Boris Johnson resigned both in disgrace and in a self-indulgent strop. Anger with the former MPs compounded the anger felt with the government. Reports from the doorsteps of Mid Bedfordshire suggest that such is the anger directed at their MP, Nadine Dorries – who has resigned in all but name but has not enabled constituents to elect her successor – that more bad news for the Tories is likely.

Ben Walker, our in-house polling guide, offered his thoughts on the by-election results in yesterday’s Morning Call. Sign up below to receive it each weekday.

5—“What happens when our protective illusions break down and we face the real world in all its stark brutality?”

Barbie and Oppenheimer are not, according to Slavoj Žižek, about a plastic doll and the father of the atom bomb. Rather, they are films in which “the heroes venture between the real and the imaginary and the imaginary and the real”. WL

After being expelled from the utopian Barbie Land for being less-than-perfect dolls, Barbie and Ken embark on a journey of self-discovery to the real world. But what they find there is not some deep revelation of the self but the realisation that actual life is even more riddled with suffocating clichés than their own fantasy world. The doll couple are forced to confront the fact that there isn’t just a brutal reality beyond Barbie Land, but that utopia is part of that brutal reality: without fantasies like Barbie Land, individuals would simply not be able to endure the real world.

Christopher Nolan’s Oppenheimer complicates this idea of venturing into reality. Its theme is not just the passage from the haven of academia to the real world of war – from the mind to the munitions dump – but how nuclear weapons (the fruits of science) shatter our perception of reality: a nuclear explosion is something that does not belong to our daily life.

bp’s transformation is underway. Whilst today we’re mostly in oil & gas, we’ve increased global investment into our lower carbon & other transition businesses from around 3% in 2019 to around 30% last year. From offshore wind to EV charging to oil & gas, see how we’re putting plans into action.

6—“Gerwig’s third feature is another departure in all respects, save an interest in female existence.”

Ann Manov, one of our film critics, has done what I’d hoped someone would do: put Greta Gerwig’s meteoric rise as a director into context. That context is, as it turns out, quite damning. HL

Defending herself against accusations of selling out, Gerwig has said, “Things can be both/and. I’m doing the thing and subverting the thing.” But the film comes across not as complex or even ambivalent about its source material, so much as indifferent. These doubts about its purpose are clear from its tagline: “If you love Barbie, this movie is for you. If you hate Barbie, this movie is for you.” But what if you just don’t care about toys? Or what if the things that make you love movies could never have anything to do with toys? The tagline reveals the profoundly IP-minded logic of the film – which, whatever Gerwig’s intentions, seems to have won the day. The appeal of the movie stems from – and ends with – the fact that you’ve seen the ads.

7—“Increasingly you realise women don’t have access to justice, essentially.”

Anoosh has interviewed a former Met police officer, Jess McDonald, who has written a book about her dismal time serving as a fast-track detective on the sexual and domestic violence team. (Anoosh has also taken a look at whether Sadiq Khan’s re-election bid is in trouble, after the “Ulez by-election” in Uxbridge on Thursday.) HL

Only 1.9 per cent of rape cases recorded by police in England and Wales result in a suspect being charged; for domestic violence, the charge rate is about 5 per cent. The men in charge told her it wasn’t her “job to care” about what happened to the many women left without justice. “They’d say: ‘If he kills her, he kills her, it won’t come back on you.’”

McDonald blamed a “misogynistic criminal justice system” – specifically, the Crown Prosecution Service’s charging standards. Time and again, she would complete an investigation only to be told by a CPS lawyer on the other end of the phone that there was “no realistic prospect of conviction”. “That doesn’t mean a crime hasn’t occurred, or that there’s not a body of evidence. They’re playing judge and jury,” she said. “It’s almost unconstitutional. It’s quite hidden, how it all works.”

8—“This is the foreseeable summer, for decades to come. Wildfires rage. Crops die, animals die, people die.”

Richard Seymour provides a chilling (sorry) commentary on another summer of extreme climate chaos. WL

As the mercury rises, so does the political temperature. In the past, world-weary, attention-seeking rightists have petitioned us to ignore woke weather warnings, cheer up and enjoy the sunshine. Far-right denialists have predictably pleaded, at the first sight of snow, for some “good old global warming”. Such levity had a certain emotional advantage for those who felt paralysed by the bad news coming from climate scientists. But, as the seasons become increasingly surreal, it is no longer convincing.

Will’s Best of the Rest

Vanity Fair: We have reached peak girl. It’s all downhill from here.

Independent: The slow death of EastEnders.

Politico: Nobody wants what Kemi Badenoch is selling.

Sun: Inside Mark Zuckerberg’s martial arts training camp. Zuck is now able to split bricks with his little finger.

Pankaj Mishra: Europe’s far-right is no longer fringe. Is Europe’s future fascist?

Grazie Sophia Christie: My beautiful friend. Exquisitely written.

James Butler: Labour’s radiant ambiguity.

Janan Ganesh: Populism gave elites more power than ever. Whoops!

Sam Bowman: Britain is a developing country.

Morrissey in Israel. The weather is better there than in Manchester.

Where writers work. Some of these desks are far too organised.

Elsewhere on the NS

Christiana Spens examines Annie Ernaux’s Simple Passion, and all the shame, confession and secrecy that flows from the novel.

“All true works of art exist in a state of withdrawal” writes John Banville, in this meditation on late style.

Emma John writes on the cautionary tale of Dele Alli, the England football star who wasn’t.

“There aren’t many people who are considered both a bona fide giant of American letters and a master of oddball tweets, but such is the peculiar mind of Joyce Carol Oates.” Imogen West-Knights meets her.

“Controlled by the imperial Treasury, Westminster and Whitehall produce weak, ineffectual institutions and endless policy churn.” Adrian Pabst critiques Britain’s failing bureaucracy.

How does it make sense to spend £1.7bn on a dual carriageway through a Unesco World Heritage Site, but not to invest in Britain’s railways, asks Jonn Elledge.

“Matt Hancock, the humiliated MP, I’m a Celebrity contestant and serial snogger, has recently traded in dress shoes for trainers because he is ‘dressed like my constituents’.” Kara Kennedy explains what on Earth it all means.

And with that…

In three pockets of Britain, voters went to the polls in by-elections this week: in none of them did a politician make a speech you will have had reason to hear, before or after the result. The three duly elected MPs will, in turn, soon give maiden speeches that pass without consequence. Will a great political speech be made in Britain again? It is difficult to remember the last.

We live in an age without oratory. Keir Starmer and Rishi Sunak are incapable of rousing crowds, or even holding the attention of an audience (both men know this, and mercifully make few attempts to do so).

Our politicians no longer have any use, in other words, for “The Scaffolding of Rhetoric”, a short piece published by a young Winston Churchill in 1897, a few years before he became an MP. In the piece – an attempt to set out “certain features common to all the finest speeches in the English language” – Churchill stresses two points.

First, speak in short words. They are more likely to be ancient, ensuring “their meaning is ingrained in the national character”. Second, we are irredeemably drawn to argument by analogy. “An apt analogy connects, or appears to connect, distant spheres,” Churchill writes. “It appeals to the everyday knowledge of the hearer and invites him to decide the problems that have baffled his powers of reason by the standard of the nursery.”

As another writer put it, we all of us, grave or light, get our thoughts entangled in metaphors, and act fatally on the strength of them. Today analogy haunts the Labour party. It is paralysed by its past, as a series of the party’s shadow ministers and strategists made clear at an event hosted by the New Statesman this week. Most notably, Labour refuses to commit to new policies on tax for fear of being miscast as profligate or punitive (as happened in 1992).

But reasoning by past error is no way to think, as Churchill argued: “Argument by analogy leads to conviction rather than proof.” Analogy and metaphor can obscure as much as they illuminate, stifling thought like “a sheet of oil spread over… a vast and profound ocean”.

Thank you for reading. Don’t miss out – subscribe to the New Statesman and stay up to date with everything you need: from news and analysis to comment and criticism.

Whether you’re looking for a sharp blog or a finely written feature, the New Statesman has you covered. Have a good week, and catch you next Saturday.

Thanks to our colleague Chris Bourn.

Possibly a cohort of the old near east countries that resulted in the making of the current Saudi tribe!

Internationally, even China is better than Saudi Arabia. Their influence is because of oil. To save the planet, we must stop oil. If we don’t, goodbye to all existence. Saudi could become powerful but there would be no planet left to rule over.